- Home

- Our Stories

- Research sheds new light on Lindstrom’s 1930 season

Research sheds new light on Lindstrom’s 1930 season

It was a small item in a baseball research newsletter, but it only added to the legacy of Freddie Lindstrom, one of the game’s immortals who today has a bronze likeness in Cooperstown.

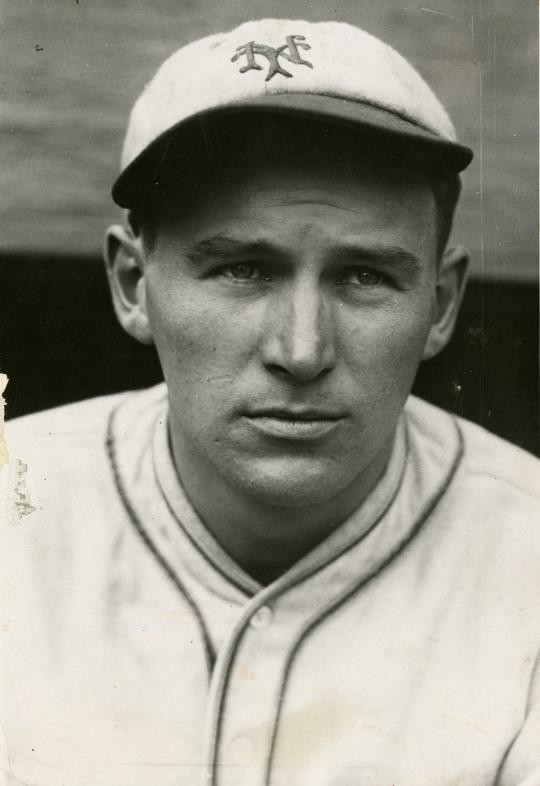

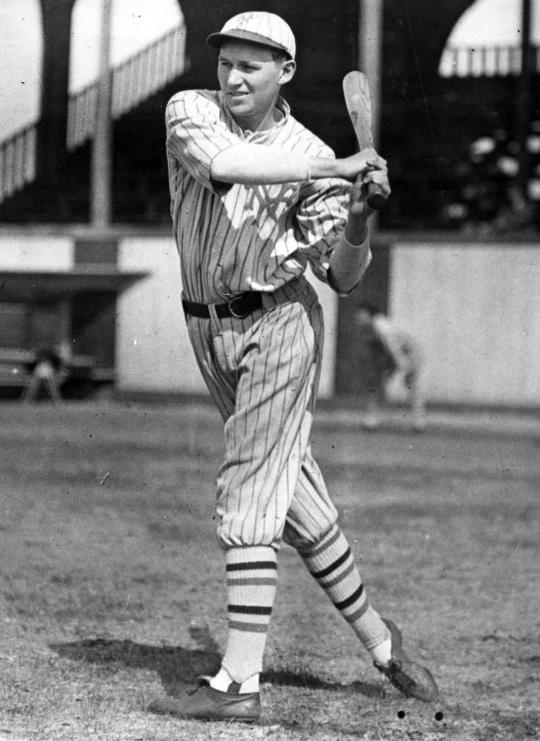

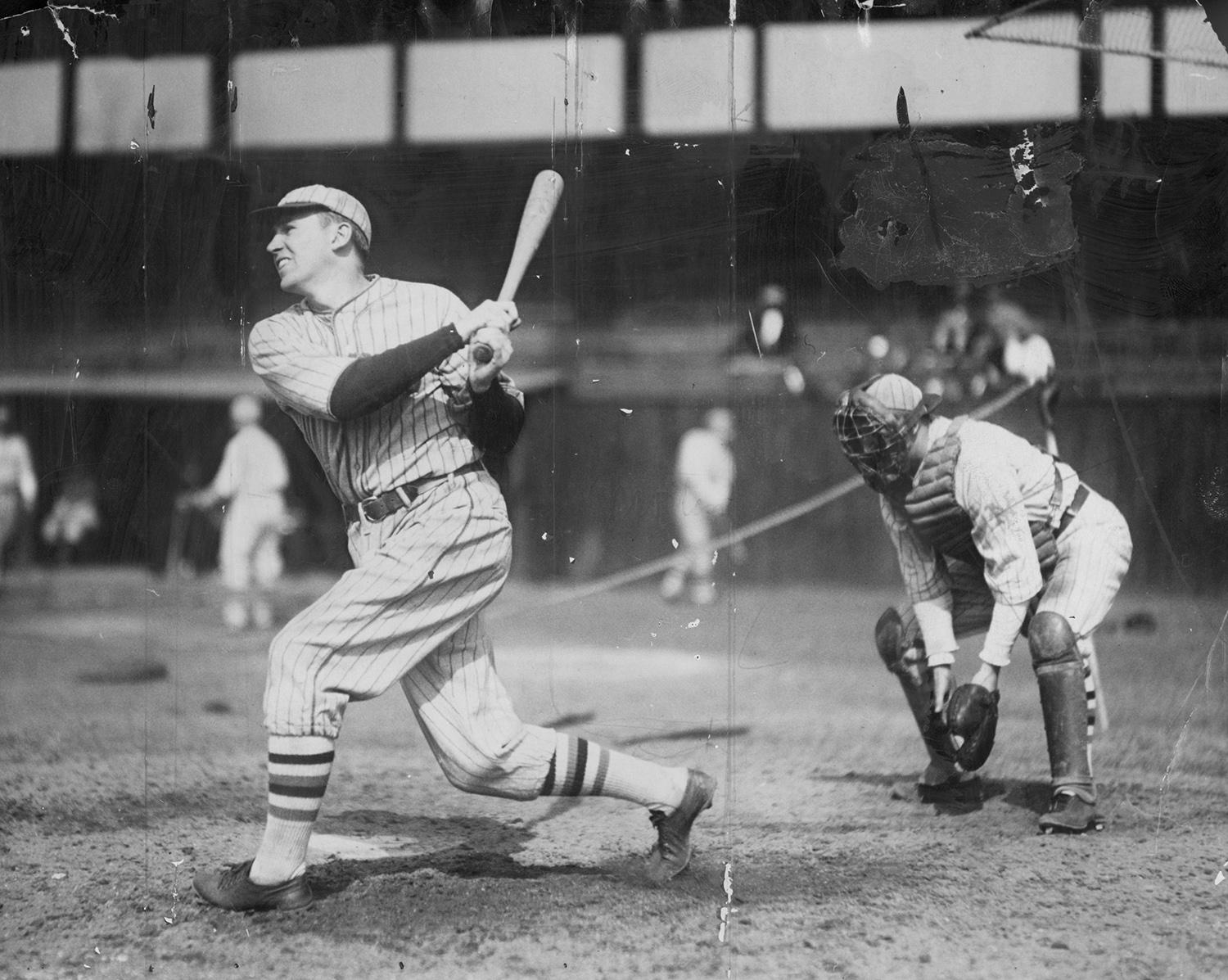

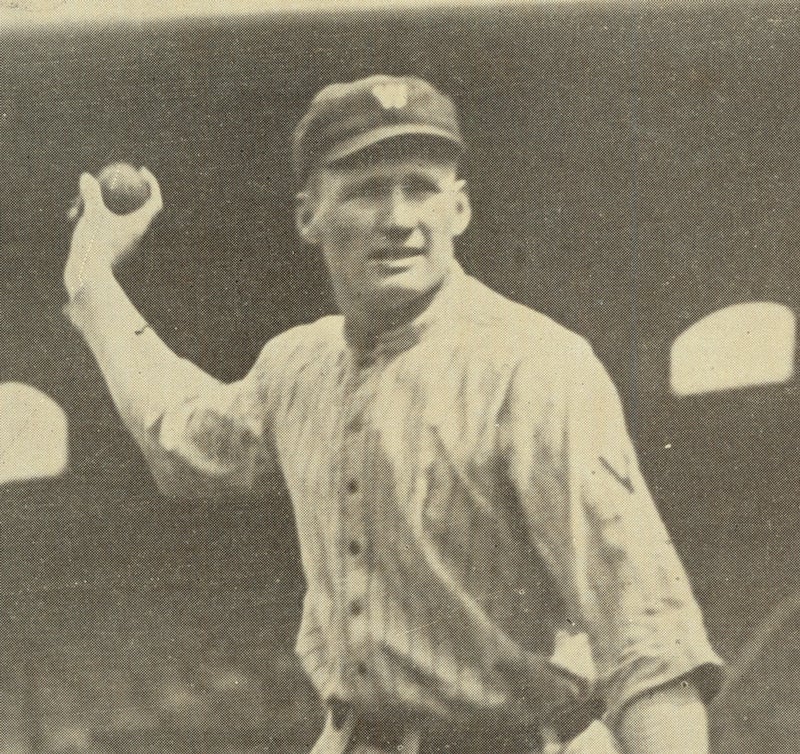

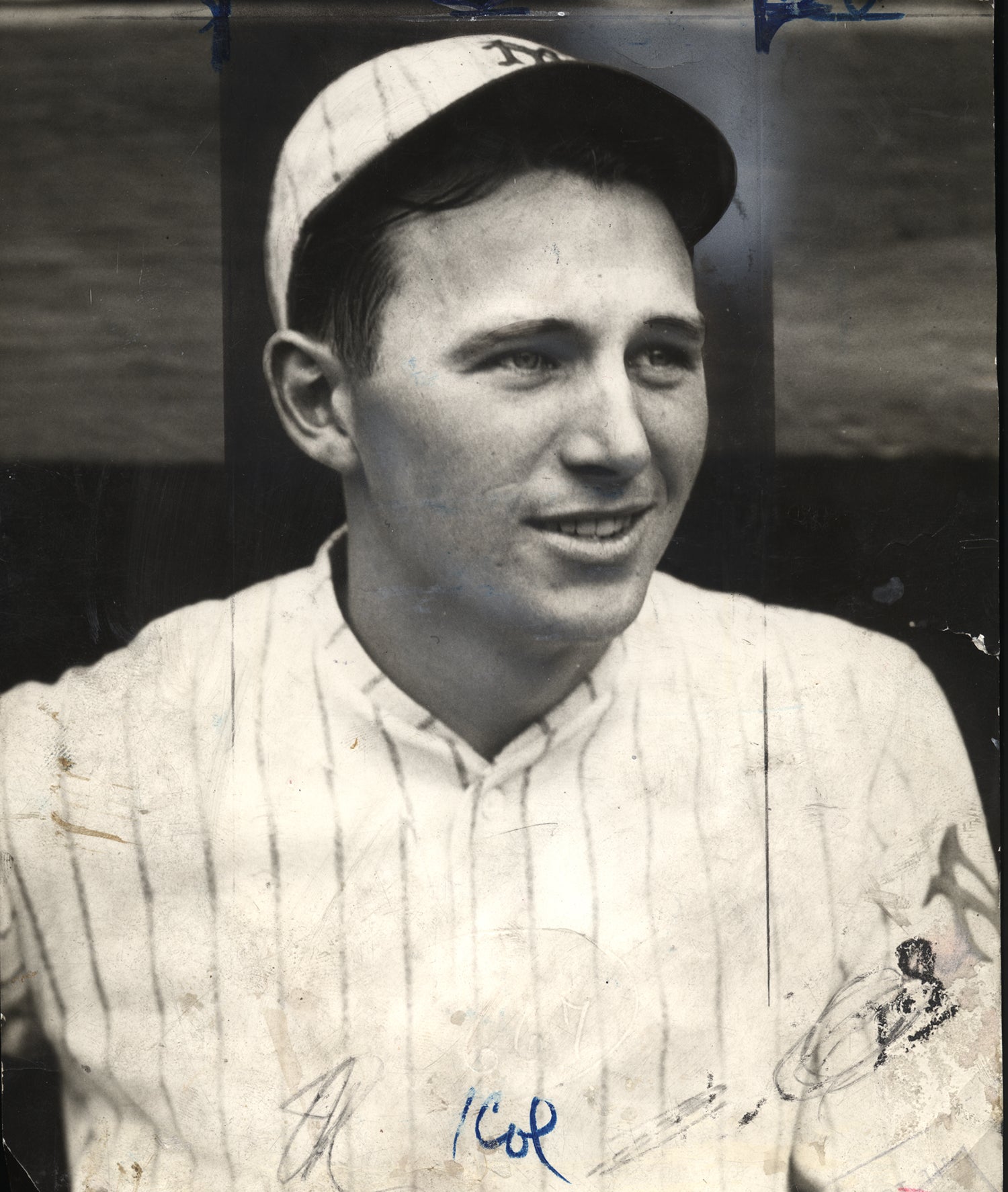

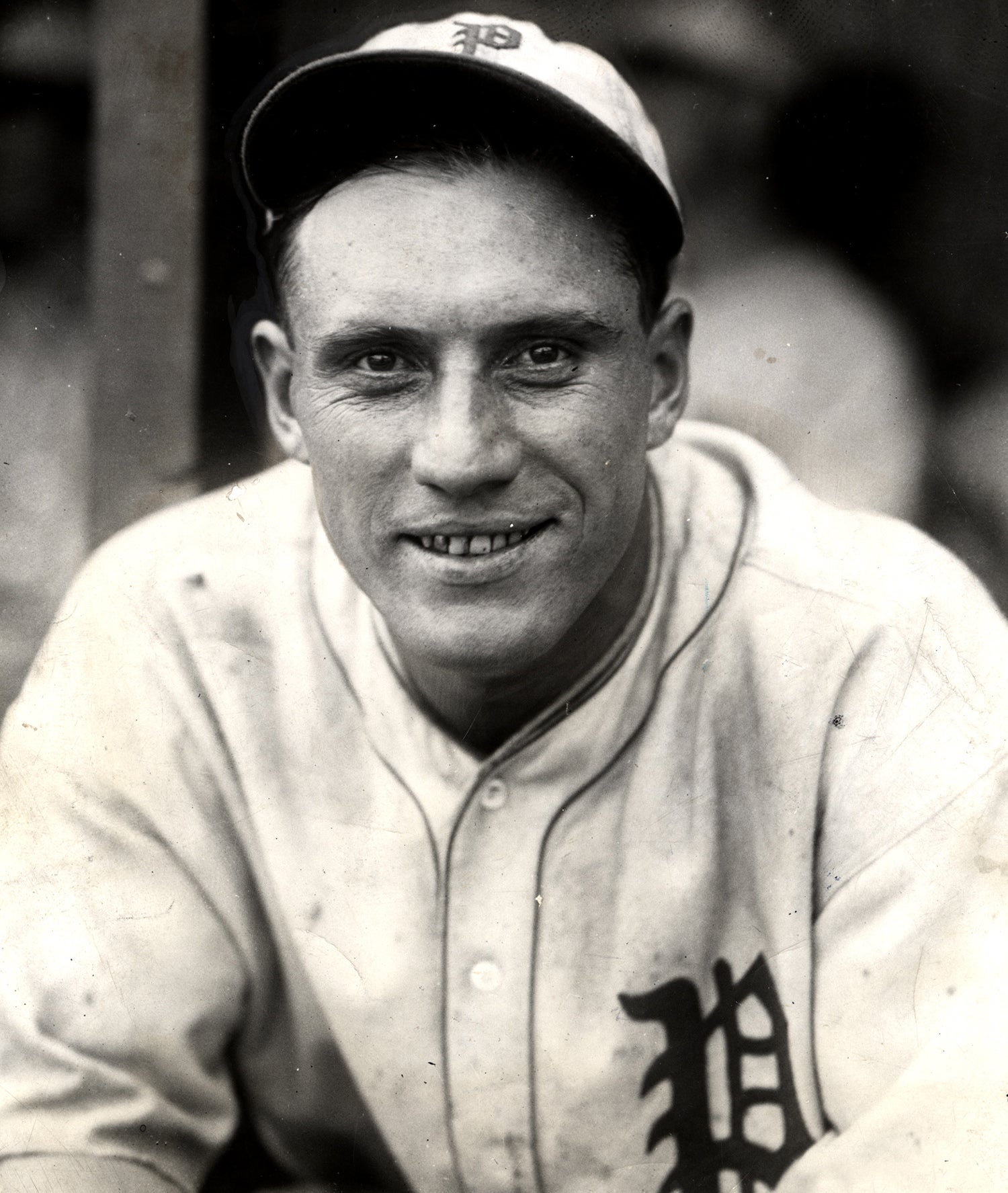

Lindstrom, a big leaguer from 1924 to 1936, starred at third base for the New York Giants for the first half of his career before making the transition to the outfield. Signed to a professional contract at 16, he made his big league debut two years later. Finishing his career with short stays with the Pirates, Cubs and Dodgers, the Chicago native had seven seasons of batting at least .300, including twice collecting 231 hits, and retired with a .311 career batting mark.

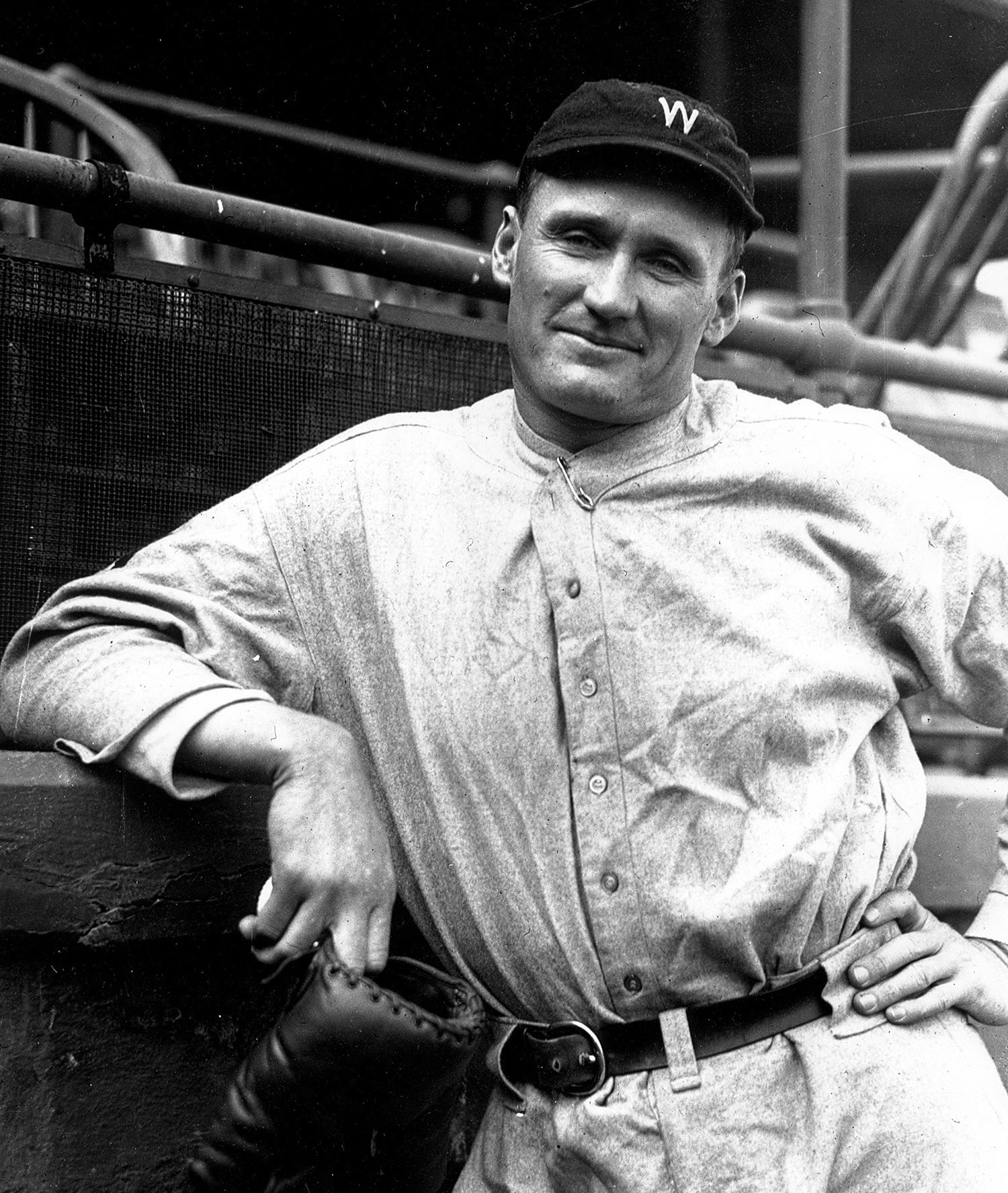

As an 18-year-old rookie, and dubbed “baseball’s boy wonder,” Lindstrom starred in the 1924 World Series after taking over for an injured Heinie Groh midseason. In the Fall Classic, he batted .333 while starting all seven games at third base, where he handled 23 chances without an error against the eventual champs, the Washington Senators, including a four-hit game against pitching great Walter Johnson. But unfortunately and infamously for Lindstrom, twice balls struck pebbles and bounced over his head for hits, the second one allowing the Senators to score the winning run in the deciding seventh game

“I was only 18 at the time and the youngest player ever to play in the World Series,” he said in 1962. “I didn’t realize the impact it would have in my life. It was just another play to me.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

“No, I have no painful memories of that Series. I’ve learned to live with it. But it’s brought up wherever I go.”

Lindstrom’s famed quick wit was on display in 1931 when, after the Giants converted him from the hot corner to the outfield, he showed up at Spring Training that year heavier than usual. “They told me I was going to be an outfielder this year,” he explained to reporters, “so I wanted to look like Babe Ruth and Hack Wilson.”

Lindstrom passed away in 1981. But thanks to some dedicated researchers, his name recently buzzed around the internet following the publication of the following note by the Society for American Baseball Research’s Records Committee:

In discussions of George Brett’s magical 1980 season, his overall .390 batting average is often mentioned alongside his .469 average with runners in scoring position, which is occasionally cited as the highest such figure in history. However, thanks to Retrosheet, we now know that Brett’s .469 figure had actually been ‘surpassed’ - fifty years earlier in 1930 by Giants’ third baseman Freddie Lindstrom, who went 59-for-123 (.480) with runners in scoring position. Lindstrom hit .379 overall that season.

The note’s author, SABR Records Committee Chairman Trent McCotter, noticed the 24-year-old Lindstrom held the record while he was “fiddling around with splits” from the Retrosheet.org historic baseball statistics website.

While Lindstrom’s 1930 season is certainly remarkable – a .379 batting average, 231 hits, 22 home runs, 39 doubles, 106 RBI, 127 runs scored, 15 stolen bases, and a .425 on-base percentage – it came during a historically robust offensive campaign in the sport’s history. Usually batting third in the lineup that season, Lindstrom had five hits in a game three times as well as a 24-game hitting streak. In September, he batted .469 (46-for-98).

National League batters hit .303 that year – only the second campaign since a .309 outburst in the 1894 Senior Circuit that the National League or American League finished with a combined batting average of at least .300. American League hitters in ’30 finished with a .288 batting average.

Despite the fact that the National League’s top hurlers in 1930 featured future Hall of Famers Dazzy Vance, Carl Hubbell and Burleigh Grimes, six of the eight National League teams had batting averages over .300, with nine qualified National League batters hitting at least .365.

Lindstrom’s team, the New York Giants, batted a combined .319, the highest single-season team average of the 20th century. Led by first baseman Bill Terry’s .401 – the last time a National League batter hit .400 – the Giants top hitters included fellow Hall of Famers such as outfielder Mel Ott (.349) and shortstop Travis Jackson (.339). Lindstrom’s .379 placed him only fifth in the National League batting race behind Terry, Brooklyn’s Babe Herman (.393), and the Phillies’ Chuck Klein (.386) and Lefty O’Doul (.383). Despite its offensive firepower, the Giants (87-67) finished third in the National League with an 87-67 record, five games behind the pennant-winning Cardinals.

“In 1930, I hit .379, which is the highest batting average of any right-hander in the National League outside of Rogers Hornsby,” said Lindstrom, who was called “the smartest hitter in the league” by enemy pitchers in those days. Since 1901, Lindstrom’s .379 batting average in 1930 is the second highest of any National League right-handed batter, with Hornsby holding down the top seven spots.

Among the other individual record-setters in 1930 were the Cubs’ Hack Wilson, whose 56 homers set a NL record and 191 RBI set a MLB record; Terry, whose 254 hits tied NL record set by O’Doul in 1929; and Klein, whose 59 doubles set a NL record.

After that 1930 season, though, there were conflicting thoughts on the explosion of offense throughout the game.

“I think the club owners ought to get together on the ball,” said Giants manager John McGraw. “It has taken the confidence out of the pitchers and is so lively the fielders cannot handle it. Bunting is gone and base-running has disappeared. The public liked that.”

“This is the age of the big punch,” said Cubs president William Veeck. “[Jack] Dempsey was an all-time outstanding heavyweight because he could punch. Ruth and Wilson are similar in baseball. It’s the punch that has made baseball over in the last 10 years. The fans don’t want to go back to the 2-1, 1-0 pitching duels of other days. With the present ball, no game – granting that only a few runs separate the teams in the eighth or ninth innings – is really settled until the last man is out. In the old days, the spectators were in the habit of leaving in the eighth if one team had a slim lead. Now they stick in expectation of a big rally. And frequently they see it.”

Despite protests from manufacturers that the ball had not changed in recent years, a move was afoot.

“My word always has been good, but I can hold up my right hand and talk until I am blue in the face on this so-called ‘lively ball’ question, and nobody pays the slightest attention to me,” said Julian Curtis, president of A.G. Spalding Co., in June 1930. “There has been absolutely no change in the major league baseball in the past five years. There isn’t even a change in the yarn. If we bought our yarn, there might be, but we don’t. We have our own yarn mills and there has been no change in the manufacture or quality; no change in the wrapping; no change in the covers; no change in the rubber or cork.”

But the National League decided to take action against the so-called "jack-rabbit" baseball at its February 1931 meeting by adding a slightly thicker cover and a more pronounced seam that will enable pitchers a much firmer grip on the ball.

“All we did was have them add about a paper-thickness of leather and bind the ball with four strands of thread instead of three,” said National League President John Heydler.

It seemed to work, as the National League went from a .303 batting average and 892 homers in 1930 to a .277 batting average and 493 homers in 1931.

“From our viewpoint, the new ball has proved a great success,” said Heydler during the 1931 season. “It has cut down the batting averages to some extent, but it has given us closer and better games. We have enjoyed excellent attendance despite the nationwide depression and feel that the improved play has had something to do with it.

“The players’ averages have suffered somewhat, but the standard of play has improved. That, after all, is the main idea. We not only think the present ball is better than the one in use last year but regard it as the best we ever have had.”

Meanwhile, Lindstrom’s career began to wind down. Though injuries contributed to Lindstrom retiring from the game in 1936 at the age of 30, he could look back at his playing career with pride.

“I hit .379 one year and fought like hell to get $18,000. They are paying some of these fellas now more than our whole team was paid,” Lindstrom said in 1979. “Sometimes you wonder how you were able to do it. Especially when they threw at you all the time. You played with the understanding that you stayed loose. They didn’t just brush you back like they do now … they threw it at your ear.”

Lindstrom’s skipper with the Giants in the 1920s was Hall of Fame John McGraw, a man known for his managerial skill as well as a quick temper.

“I was a line-drive hitter. I had good power but never tried for the long ball. Nobody did back then. You protected the plate – especially if you played for John McGraw,” Lindstrom recalled in a 1976 interview. “Do you know what the cardinal sin was on that ball club? To begin a sentence to McGraw with the words, ‘I thought.’... ‘You thought?’ he would yell. ‘With what?’”

Among Lindstrom’s prized possessions, and one he always carried with him later in life, was a yellowed 1930 newspaper clipping in which McGraw rated in order the 20 greatest baseball players he had seen in his lifetime. Lindstrom was ninth on the list, behind such luminaries as Honus Wagner, Ty Cobb, Willie Keeler, Eddie Collins, Babe Ruth, Tris Speaker, Rogers Hornsby and Nap Lajoie.

After serving as a minor league manager for three seasons (1940-42), Lindstrom returned to his home in the Chicago area. Soon he found work as the baseball coach at Northwestern University for 13 years (1949-61) and a postmaster in Evanston. Ill., a position he retired from in 1972 after 17 years.

In February 1976, it was announced that Lindstrom had been unanimously elected by the Veterans Committee to the National Baseball Hall of Fame. Lindstrom was one of three candidates elected by the Veterans Committee, the others being 1890s slugger Roger Connor and umpire Cal Hubbard.

“I’m overwhelmed,” said the 70-year-old Lindstrom upon learning the news. “I’m very happy that the Lord allowed me to live to enjoy this day. There are so many others that are under consideration that you never feel like you will be the one until it is announced.

“It’s the greatest thrill I’ve ever had. If I live to be 100, it will never be topped.”

Lindstrom heard the news of his election from a yelling neighbor after completing a round on the Beacon Woods Golf Course near his retirement home in Florida’s Pasco County.

“I had an 80, believe it or not,” said Lindstrom. “That’s a little better than my average day.”

Bill Francis is a Library Associate at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum