- Home

- Our Stories

- #Shortstops: The amazing Jackie Price

#Shortstops: The amazing Jackie Price

Baseball scouts are always on the lookout for five-tool prospects: Those who can hit, hit with power, and run, field, and throw all very well.

Talents scouts look for other attributes.

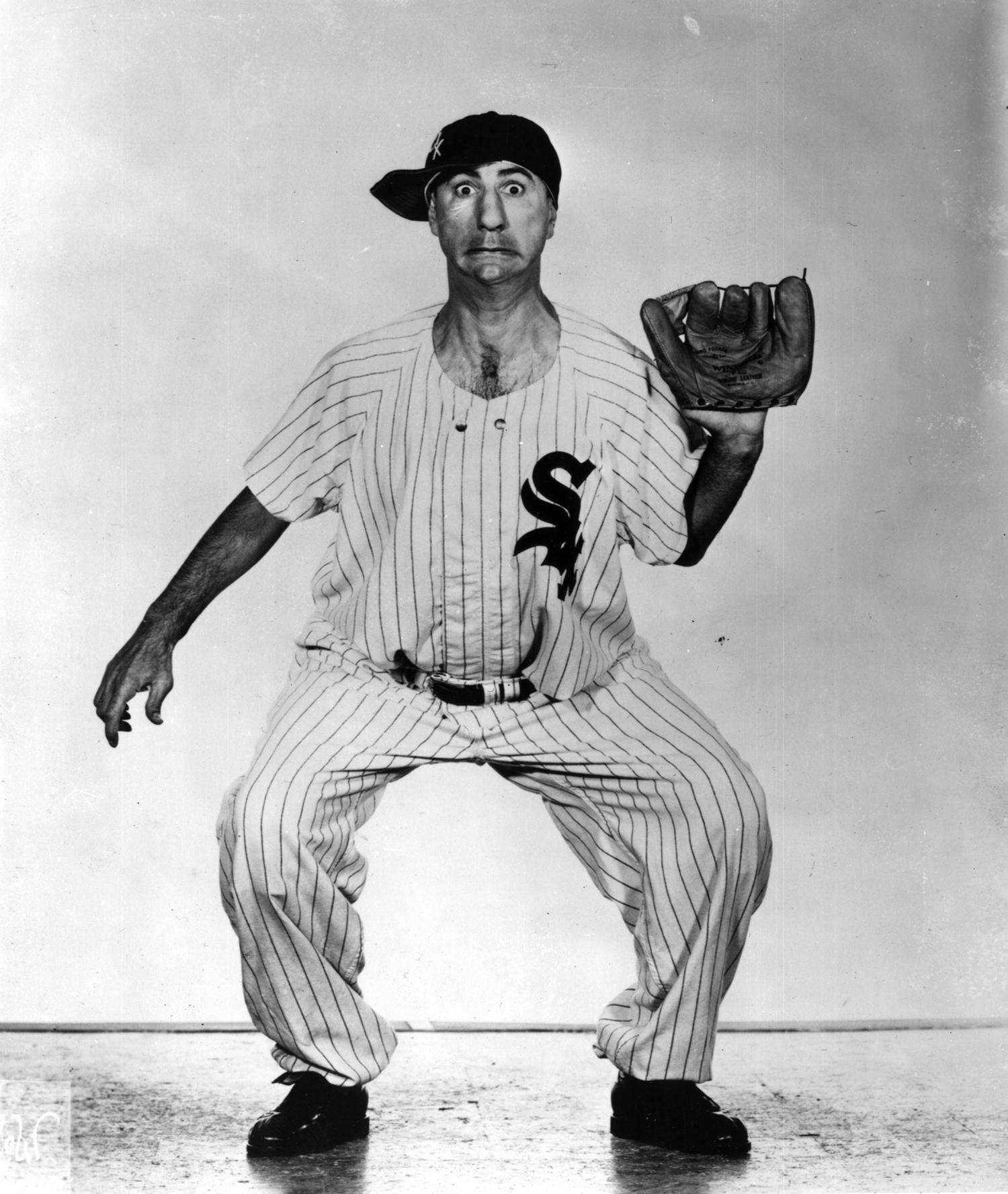

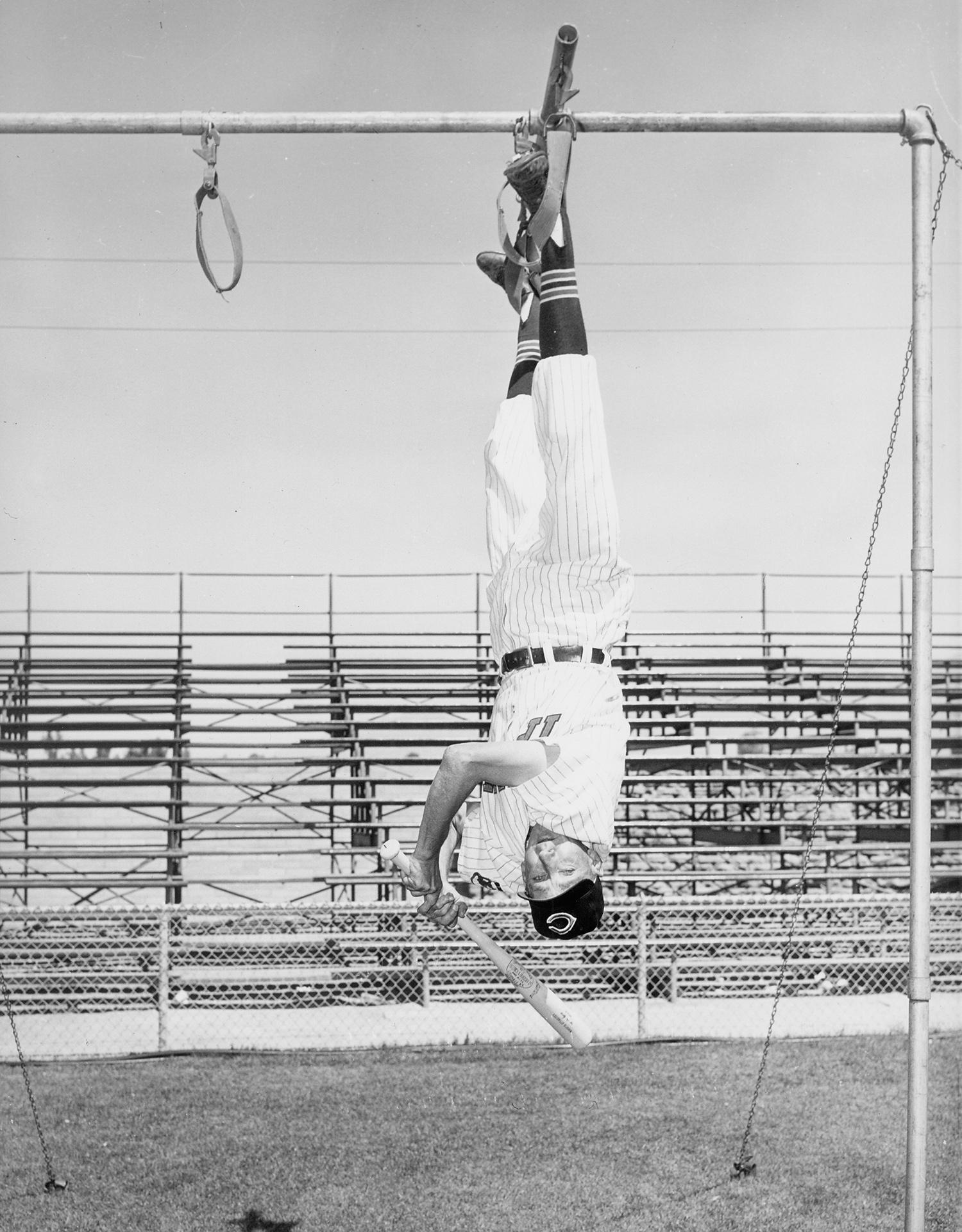

In this case, someone who could throw three baseballs simultaneously and accurately, each to a different receiver; someone who could hit two baseballs at the same time, each toward a fielder in opposite directions; and someone who could catch and throw baseballs while constantly driving a Jeep in a circle.

In other words, someone like Jackie Price.

Price, whose given name was John but who also went by Jackie, was born in 1912 in Mississippi and grew up in the Memphis area. After a decade of playing baseball in the minors, as well as in independent and semi-professional leagues, he signed with representatives of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) to develop a short movie based on his unique skills.

The film would be titled “Diamond Demon.” You can find it here.

How Price developed his talents and got to MGM is a story itself.

It is said that Price began his tricks while in high school, where he also starred as a pitcher in addition to his solid infield play. After playing semipro ball, Price entered the minors in 1935 with the Class D Union City (Tenn.) club. He advanced to Class B Asheville (N.C.) in July 1936, where the Citizen-Times newspaper reported he “should add considerable strength to the infield, defensively, if reports about his ability are true.”

An average hitter but much better defensive shortstop, Price further developed his stunts during a stint with the US Army’s ordnance corps during World War II, using them to entertain servicemen in California. After receiving a medical discharge, the Columbus (Ohio) Red Birds picked up Price for the 1944 season. According to the Indianapolis News, which called him a “one-man circus,” Price signed two contracts: One to play ball and the other for his stunt work.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Price’s pre-game or between-games acts made the rounds during the 1944 American Association season, with the Minneapolis Star offering a “bouquet” to Price for “his acrobatic stunts in catching and throwing a baseball” between games of a doubleheader between Columbus and Minneapolis. The Star noted that Price “was a dexterous as a House of David pepper baller.” The Tribune in Minneapolis offered some photographs of the stunts, where Price was assisted by teammate Wesley Cunningham.

An article published across many newspapers in late August 1944 called the act a “comedy sequence” drawing raves and comparing Price to other “intentional and unintentional baseball clowns,” such as Nick Altrock and Al Schacht. The Sporting News, in 1965, deemed him a “comedian,” which Cunningham took affront to in a letter to the editor.

Cunningham and Price were teammates in Columbus and later in Oakland, and “during those years, I threw to Jackie possibly more than any other player,” Cunningham wrote.

“I was familiar with his show and I think the word comedian belittles Jackie and his talent.

“At nights in our room, he was always thinking of ways to improve his show. I have seen his body black and blue and seen him so tired after a show and game that he would shower and go to bed without drying off. I have never seen anyone in baseball try to duplicate his show. He was definitely no comedian.”

If Price was no comedian, he could list snake charmer among his talents. He captured 12 bull and king snakes while stationed near the Mojave Desert, the biggest being more than six feet long. The snakes were part of his act, but early in 1944, one woman fainted and “a couple of others went into hysterics” during a performance in Toledo. George M. Trautman, American Association president, outlawed the snakes as a result. It wouldn’t be the only issue others had with his snakes.

Price proved he could still play ball, however, it was clear Price was becoming less of a valued asset and more of an act. The Louisville Courier-Journal, in a preseason look at the 1945 American Association season, noted for Columbus that “Johnny Price, the entertaining clown, is at third base and will stay there until somebody better takes the job.”

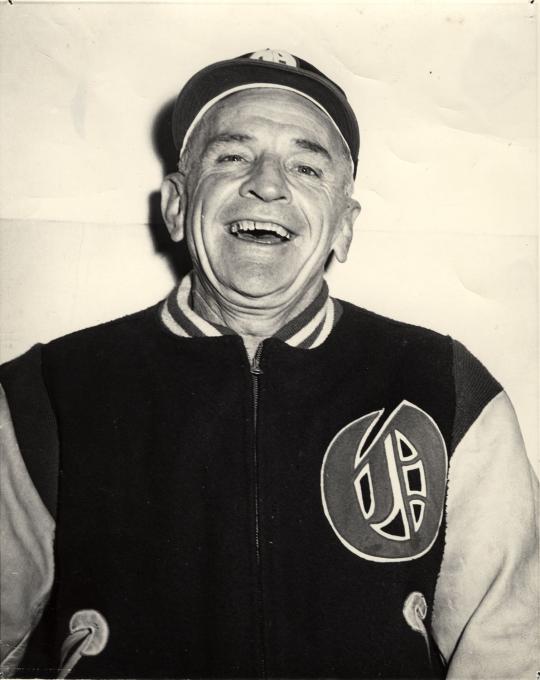

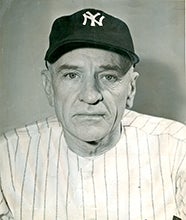

He split the 1945 season between Columbus and Milwaukee, and the Brewers sold Price to the Oakland Oaks of the Pacific Coast League in January 1946. The sale apparently occurred at the insistence of Oaks manager Casey Stengel.

Bringing his act back to the west coast at Oaks’ training camp at Boyes Springs, Calif., near Sonoma, Price’s “performance completely stole the show from a Hollywood movie company filming all Pacific Coast League teams in training,” the Oakland Tribune reported.

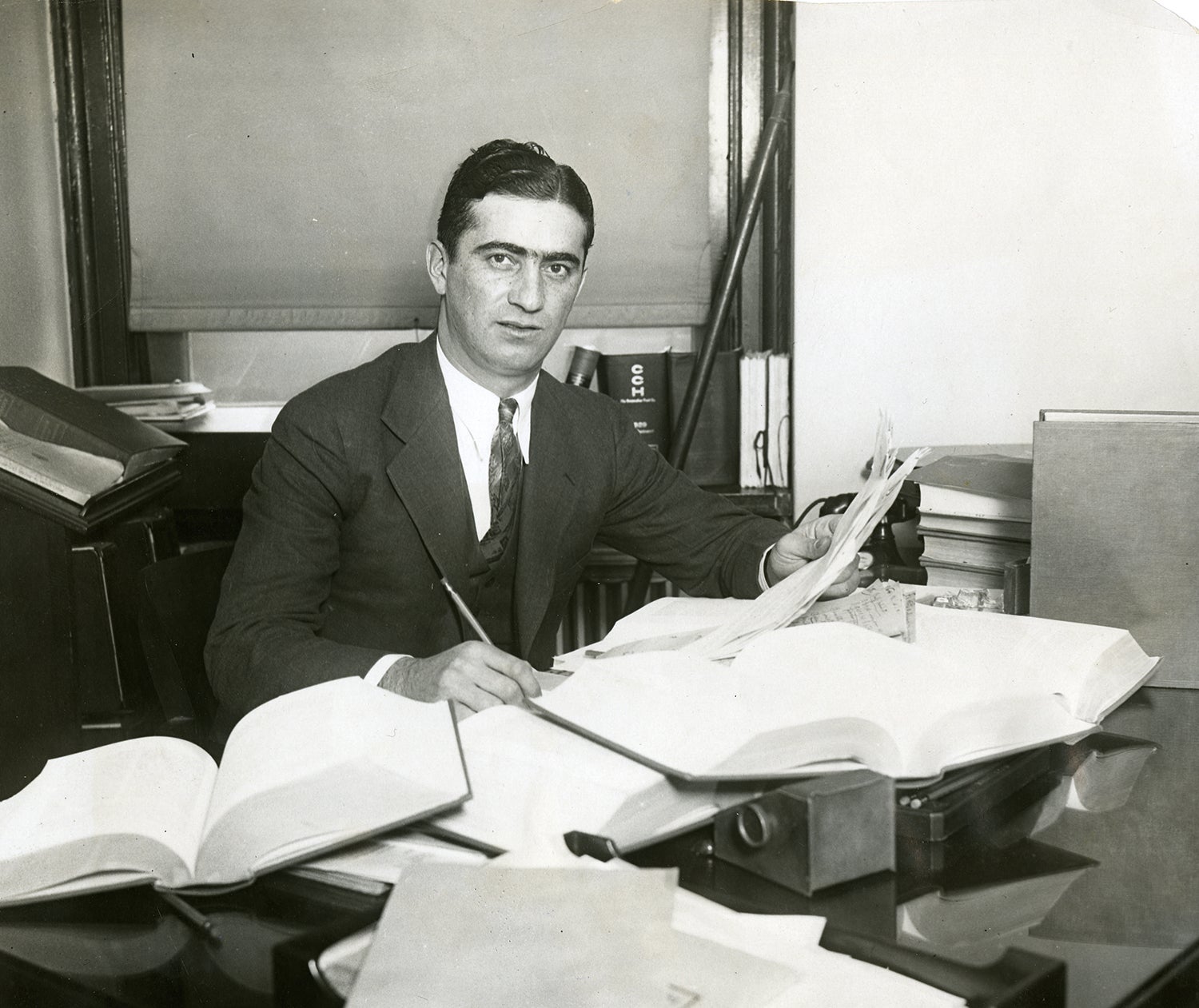

MGM and producer Pete Smith decided to develop a movie short surrounding Price and his stunts. Newspapers reported that Price “will pick up a nice piece of change” for being the star attraction of the movie, initially scheduled to be shot on the MGM lot in Culver City. Joining Price – but only earning $35 per day – were teammates Billy Raimondi, Floyd Speer, and Bill Hart.

Price featured several of the 108 tricks he had in his repertoire, and it was deemed “motion pictures are the only medium that can show exactly what he can do,” even if, during downtime, Price and “his supporting cast … are having a fine time playing catch with the assistants on a spot of lawn … in the midst of the phony splendor of the movie sets on the huge M-G-M lot.”

The Los Angeles Times said that if a doubleheader between Los Angeles and Oakland turned out to be dull from a baseball perspective, “the show will be worth the price of admission. Because Johnny Price, Casey Stengel’s stunt man, is going to put on his act. And if you haven’t seen it, you haven’t lived, baseballically speaking.”

Price may have been limited to 22 games as a player for Oakland in 1946, but he would not limit himself to outdoor shows. An indoor routine Price developed would make him “baseball’s gift to clubs, lodges, school assemblies and all similar groups seeking an entertaining act for free,” according to the Oakland Tribune, which described the new routine as a “thriller-diller.”

Seeking another act for his ballclub, Cleveland Indians owner Bill Veeck purchased Price from Oakland, it was announced on Aug. 2, 1946.

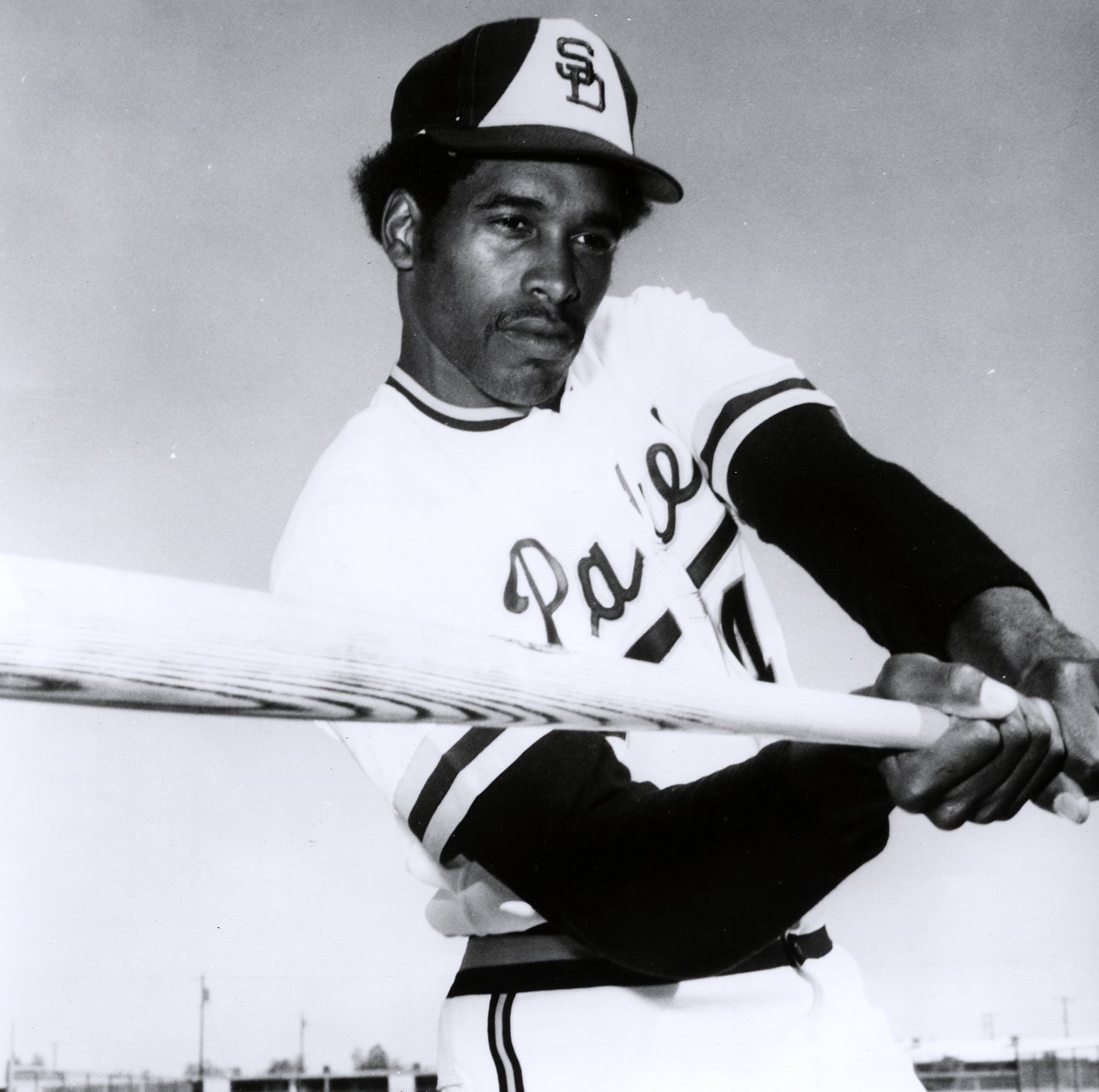

Jackie Price played for future Hall of Fame manager Casey Stengel during his stint with the Oakland Oaks. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

“Wait until you see this fellow,” remarked Veeck. “He’s no phenom and he won’t hit much. I don’t think (manager and starting shortstop) Lou Boudreau will have to worry about the competition – but before that game starts, he’s a riot.”

Veeck wasn’t done either. A week later, he acquired clown Max Patkin from Oakland. News reports said “Patkin is not supposed to be much of a pitcher but reputedly is one of the funniest men in the game. … He will team with Johnny Price, the new Indian infielder with a bag of tricks.”

Price made his major league debut on Aug. 18 against Chicago, delivering a ninth-inning pinch-hit sacrifice hit as Cleveland rallied to tie the game, forcing extra innings. It would be one of seven games he would play in the majors, batting .231 (3-for-13) with one run scored, but he provided much needed laughs for Cleveland fans suffering at the end of a miserable season.

His drawing power was such that Indians ace Bob Feller took Price with him on his offseason barnstorming trip. Price and Patkin joined Cleveland for Spring Training in 1947. At the same time, Price’s short film, “Diamond Demon,” was hitting movie theaters, promising filmgoers “ten minutes of diamond dexterity.”

However, while the Indians were en route from Los Angeles to San Diego in March, Price let loose two five-foot snakes on the team’s train. Allegedly, a train brakeman wanted Price to have fun with some members of a women’s bowling team, and Price complied by tucking some snakes inside his shirt. The ensuing clamor alerted the train conductor, who then notified Boudreau.

“The conductor went in and ate out Boudreau before Lou even knew what it was all about,” Price said. “There was nothing for Lou to do then but eat me out.”

Boudreau explained that he was manager of a ballclub and not a ringmaster.

“I hope I can see a joke as well as anyone,” he said, “but this is a big league club, not a traveling circus.”

Veeck, who signed Price to a year-round contract as an entertainer and a dollar-a-year contract as a coach, sat down with Price and forbade the snakes from returning.

Price would continue to perform his stunts at ballparks and other venues across the continent, with his career lasting well into the 1950s. He returned to the Bay Area, where he remained for the rest of his life.

Matt Rothenberg is a freelance writer from Ossining, N.Y.