- Home

- Our Stories

- Clowning Around with Nick Altrock and Al Schacht

Clowning Around with Nick Altrock and Al Schacht

Baseball has always been full of hilarious antics from all corners of the field. From endlessly creative clubhouse pranks to the tradition of dumping full, icy coolers over players or coaches – not to mention anything regarding mascots – fun and games are as much a part of the baseball experience as pitching and batting. But before these were staples of the game, there were Baseball Clowns, including two of the most famous clowns from the first half of the twentieth century, Al Schacht and Nick Altrock.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Altrock was the older of the two comedians, born in 1876, 16 years Schacht’s senior. However, they had similar beginnings. Both were children of immigrants; Altrock’s family was German and settled in Cincinnati, Schacht was born to Jewish Russian immigrants in the Bronx. Both men knew they wanted to be professional ballplayers from a young age and despite parental disapproval, bounced from team to team in the semipro leagues through their young adulthood.

Altrock was picked up by the Boston Americans at the end of the 1902 season, but was quickly traded to the Chicago White Sox. He performed well there, and picked up the win in Game 1 of the 1906 World Series. However, early in 1907, an injury to his arm made him largely ineffective as a pitcher, and by early 1909 he was traded to the Washington Senators and relegated to the minors. While coaching a few years later, he caught the attention of Clark Griffith, manager of the Senators, for his solo pantomime comedy skits he would do from the sidelines during games. He was brought up to the big leagues as a “comedy coach”.

Just as Altrock was getting his comedy act started with the Senators, Schacht was trying his hand at clowning in Walton, N.Y., where he was pitching for a semipro team. He would do impersonations and pantomime during social events before games, and fans ate it up. But he was desperate to play big league ball and started reaching out to Griffith anonymously about his pitching performance. Griffith eventually signed him at the end of the 1919 season. The following year, a mid-game collision ruined Schacht’s shoulder, effectively ending his pitching career.

Altrock and Schacht had met during Spring Training just a few months earlier. They disliked each other almost immediately: Altrock was territorial about his comedic role on the team and allegedly lobbed slurs at Schacht during arguments. Schacht hurled balls at Altrock’s head in retaliation. But by midseason, they both were washed-up pitchers, both now coaching for the Senators, and understood their comedy routine could lengthen their days in professional baseball.

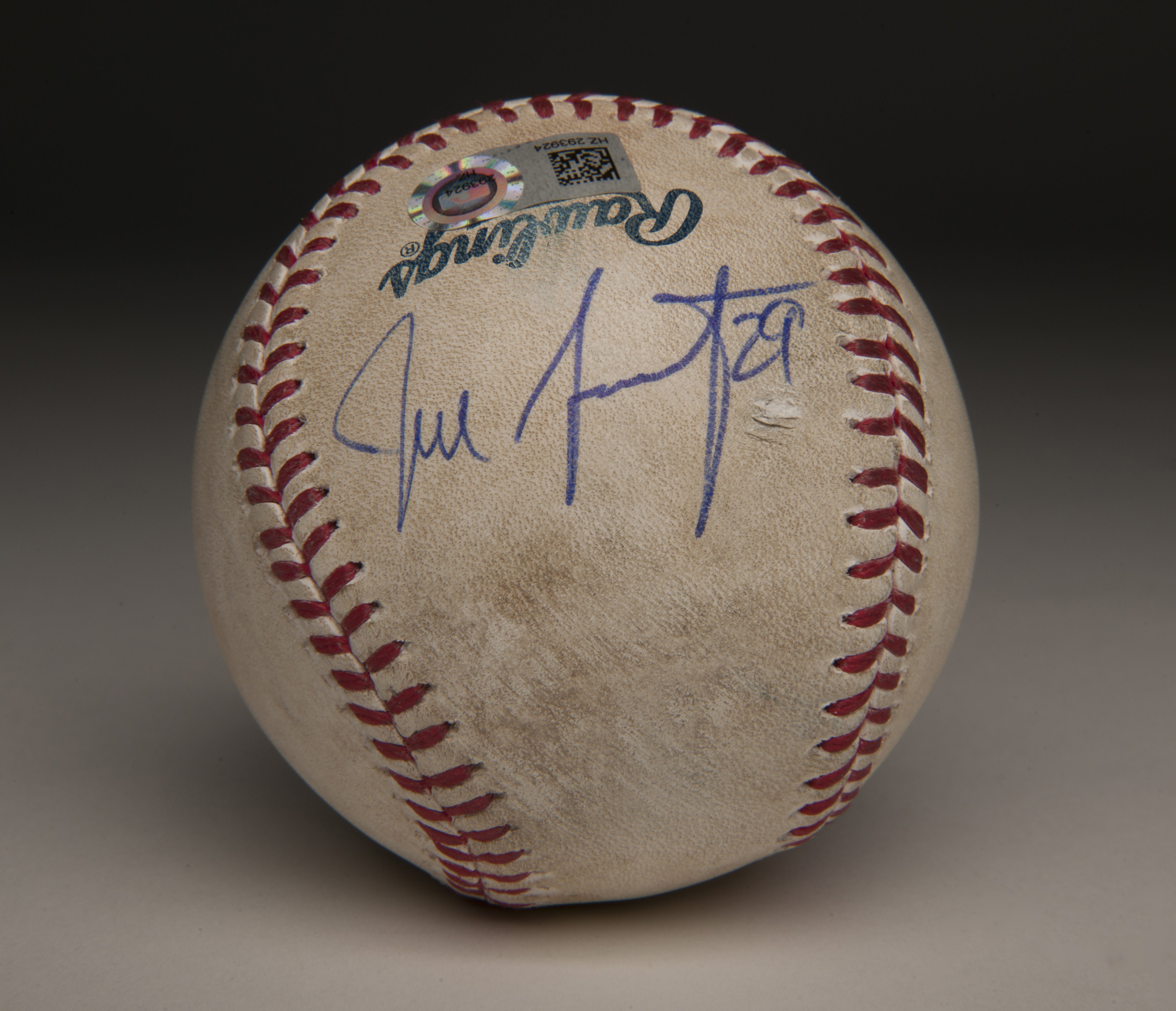

And it worked. Fans adored them, and they became staples at every Senators game. Schacht would wear a swallowtail tuxedo jacket and top hat, now part of the Hall of Fame’s collection, and occasionally ate a fine meal on home plate between innings. Altrock would wrestle himself and pretend to spike himself with his own cleat. Together, they often used oversized gag equipment, like the large glove also in the Museum’s collection, or raided the Washington Redskins football equipment to mix the two sports on the field the two teams shared. They boxed each other, rowed boats during rain delays, and pantomimed all manner of absurd scenarios. In 1922, the two were hired to perform at the World Series. Their salaries rivaled the great players of the era, including Babe Ruth, who was one of their biggest fans.

Nick Altrock and Al Schacht often used gag equipment at games, like this oversized glove now preserved in the Hall of Fame's collection. a href="https://collection.baseballhall.org/PASTIME/nick-altrock-oversized-glove-undated-0">PASTIME (Milo Stewart Jr./National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

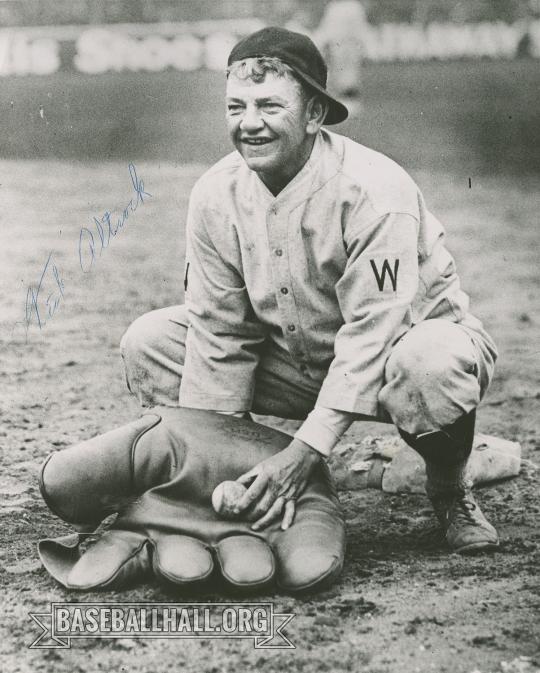

Washington Senators pitcher Nick Altrock poses with his large baseball glove. PASTIME (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

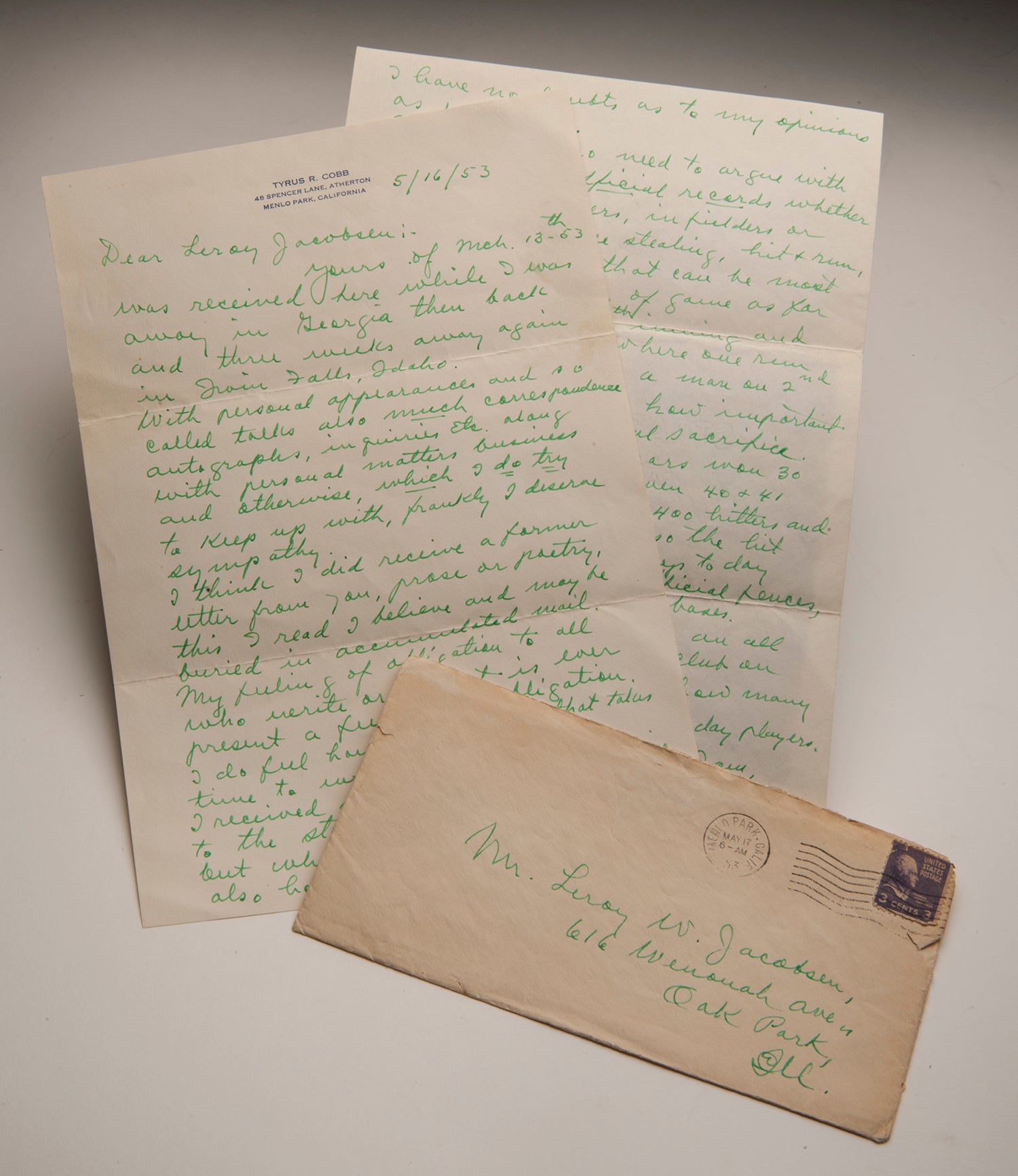

Nick Altrock (left) and Al Schacht were two of the most famous baseball clowns of the first half of the 20th century.. PASTIME (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

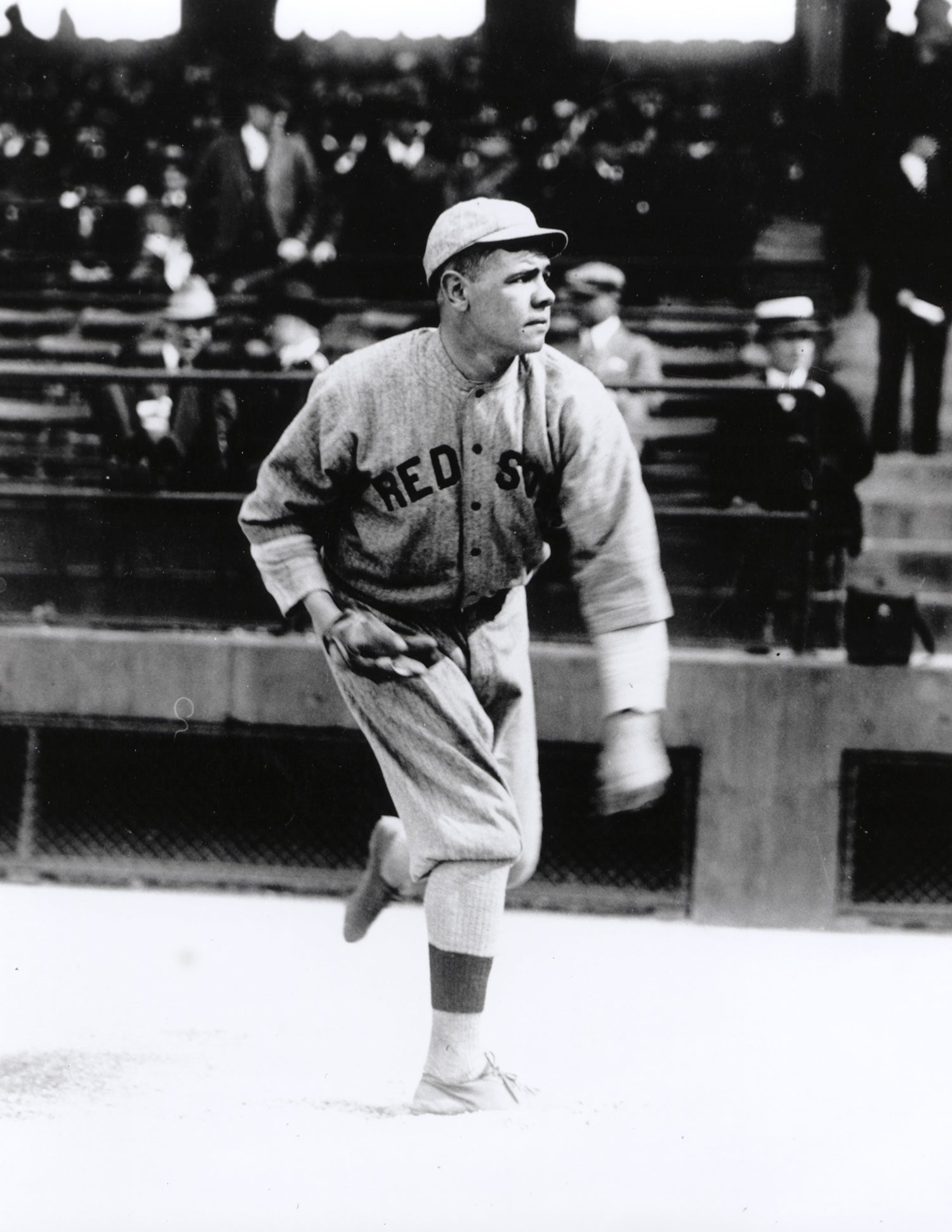

As part of his Baseball Clown routine, Al Schacht (pictured above) would wear a swallowtail tuxedo jacket and top hat, now part of the Hall of Fame’s collection, and occasionally ate a fine meal on home plate between innings. PASTIME (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Their partnership kept them with the Senators for more than a decade. Schacht moved to the Boston Red Sox in 1934 and broke up the act. But both clowns continued their performances solo. Altrock was with the Senators until 1957 as both coach and entertainer. Schacht performed all over the country until the United States’ entry into World War II, when he toured the world performing for the troops and retired upon the war’s end.

As we brace ourselves for the most prank-filled day of the year on April 1st, take some time to appreciate the men that filled stadiums with laughter and added a new dimension of hilarity and fun to the National Pastime.

Peyton Tracy is the registrar at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum