- Home

- Our Stories

- #Shortstops: Bill Stewart’s career as an official swept through MLB, NHL

#Shortstops: Bill Stewart’s career as an official swept through MLB, NHL

At face value, it could just be any old whiskbroom that an umpire would use to dust off home plate – a somewhat inexpensive tool to accomplish a relatively mundane task.

But it is the story of the person who once owned the broom that is much more interesting.

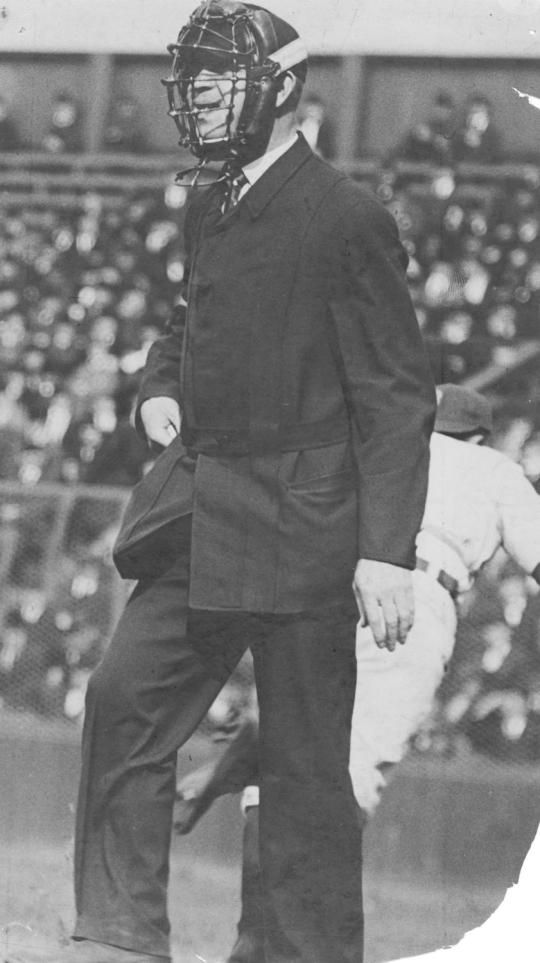

That would have been longtime National League umpire Bill Stewart. Stewart, an arbiter in the senior circuit from the 1933 through 1954 seasons, donated the well-worn broom to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1954. He claimed to have used this broom in at least 1,000 games, and according to Retrosheet.org, he officiated in 3,192 regular season games, 23 World Series games, and 4 All-Star Games. When he left the National League in early 1955, his 3,192 regular season games umpired ranked in the top 15 among major league umpires.

Born in 1895 in Fitchburg, Mass., Stewart played several seasons of minor league baseball, mainly as an outfielder and pitcher. On Jan. 4, 1919, The New York Times announced he signed with the Chicago White Sox after compiling a 16-1 record playing ball while in the U.S. Navy in 1918. Stewart attended Chicago’s Spring Training camp in Mineral Wells, Texas.

“Stewart was the only stranger among the day’s increment (of White Sox arrivals), and he had no difficulty in finding the club’s headquarters – by telephone,” the Chicago Daily Tribune’s I.E. Sanborn reported.

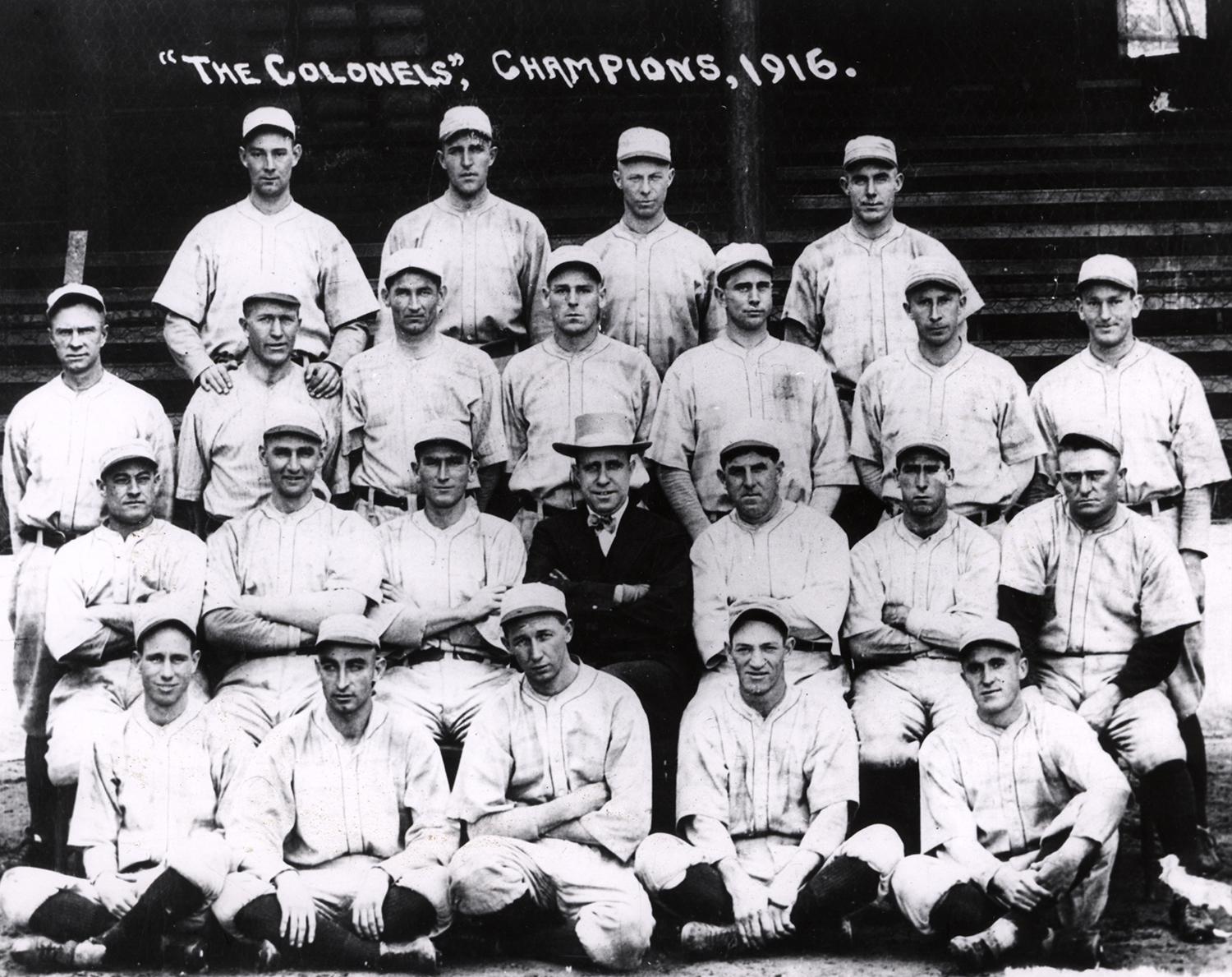

While Stewart appeared in some White Sox exhibition games, he never played for Charles Comiskey’s club in the regular season, instead spending the 1919 season in Louisville rather than on the eventual American League pennant winner. After a five-year break from professional baseball – during which time he appears to have scouted for the Red Sox and coached Harvard’s baseball team, among other jobs – Stewart’s last years in minor league dugouts (1927, 1928, and 1931) were spent mostly in managerial roles, though he often inserted himself into the lineup in 1927 and 1928.

Stewart spent the next few springs and summers as an umpire in the International and New York-Penn Leagues before moving up to the National League late in 1933. His first major league game occurred on Sept. 23 behind the plate at the Polo Grounds, where he used the whiskbroom for the first time. The next year, he would join the NL staff on a full-time basis.

Upon his arrival at Boston Braves Spring Training camp in March 1934, John Kieran of The New York Times wrote about Stewart for his “Sports of the Times” column.

“He is the only big league hockey arbiter among the major league umpires. He is a chunky chap with a fine crop of dark hair – until he takes off his cap,” Kieran wrote. “The doffing of his chapeau discloses a large area of shining dome. He accounts for the denuded area by putting the blame on too many shower baths, but he was once a right-handed pitcher in half a dozen leagues and it may be that his top thatch was burned off by scorching liners coming back through the box.”

Baseball was a fine sporting option for Stewart during warmer months, but the chill of winter necessitated another pastime. Growing up in Boston, winters meant hockey. Stewart was very involved in Boston-area hockey circles, coaching a variety of amateur teams and officiating for others.

On Feb. 24, 1923, Stewart was one of the referees for the second game in a best-of-three series between Princeton and Harvard at the new Hobey Baker Memorial Rink in Princeton. Deemed by The New York Times correspondent as “one of the cleanest” games played at Princeton that season, Stewart found himself the center of attention.

“In the heat of the battle in the third period Referee William Stewart fell, striking his head on the ice with such force as to be knocked out temporarily,” the Times correspondent noted after the Crimson’s 2-1 win.

Fortunately, he recovered to finish the game and returned several days later to referee the third game of the series.

In 1927, when he took his first professional managerial job with Nashua of the Class-B New England League, Stewart had just spent the 1926-1927 hockey season as a referee for the Canadian-American League.

Working his way up the ranks to head referee in the Canadian-American League, Stewart in Nov. 1931 received a full-time referee appointment with the National Hockey League, with whom he had occasionally officiated games as early as 1928. First, though, he had to resign from the hockey coaching staff at M.I.T. after a six-year coaching tenure there.

According to a Boston Globe story regarding the naming of Stewart’s successor, “the announcement [came] as a pleasant surprise to the student body.”

It is not clear whether the “pleasant surprise” was Stewart’s resignation or the choice for the new coach.

Stewart’s tenure in the NHL was not always smooth. He was intimately involved in one of the league’s few forfeited games.

The March 14, 1933, game between Chicago and Boston went into overtime, and the Bruins appeared to score the game-winning goal. The Blackhawks rather vociferously disputed the ruling, believing the red light had gone on prior to the puck entering the goal.

“The Hawks [coach Tommy Gorman] called referee Stewart over and at once handed a healthy punch. Stewart returned in kind,” the Boston Globe said. “There was a rapid exchange of blows and only the strength of (Boston’s) Alex Smith who teams with (Eddie) Shore kept Stewart from climbing over the boards.”

With the Blackhawks leaving the ice after the fracas, Stewart declared a forfeit in favor of Boston.

In Dec. 1936, Stewart was the referee in a game between the New York Rangers and New York Americans – one which featured, the Associated Press claimed, “the liveliest fistic ‘Donnybrook’ in several seasons.” Police were called in to help alleviate the fighting.

By 1937, Stewart was the NHL’s referee-in-chief, but that spring, he hung up his whistle to become the head coach of the Chicago Blackhawks. He was in Chicago to umpire several Cubs home games when he met with Blackhawks owner Major Frederic McLaughlin to sign his contract.

Upon hearing the news, Kieran suggested it would “give him a decidedly different outlook on the ice. Maybe Bill just wants to see how the other half lives.”

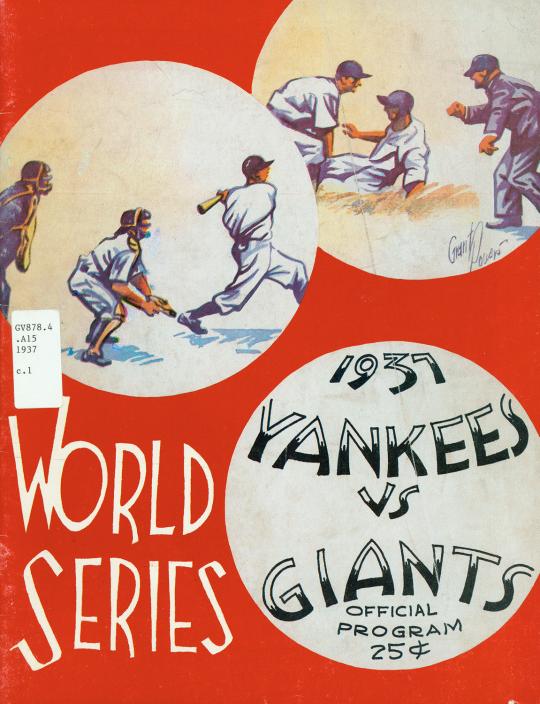

Though he intended to be there on time, Stewart missed part of Blackhawks training camp thanks to an assignment to umpire the 1937 World Series, his first Fall Classic. A non-contender in the 1936-1937 season, Stewart’s Blackhawks were a heavy underdog in the playoffs, thanks to their well-below sub-.500 record. Yet they caught fire in the postseason and hoisted the Stanley Cup at the end, with Stewart becoming the first American-born head coach of a Stanley Cup-winning team and the first individual to win the Cup in his first season as a coach.

Umpire Bill Stewart had a working relationship with Hall of Famer Bill Klem (pictured above). Stewart was named supervisor of National League umpires by Ford Frick, a position formerly held by Klem, but opted to not accept the position while Klem was alive. (National Baseball Hall of Fame)

Share this image:

Stewart was confident that his team could make another run for the playoff title.

“My contract with the Hawks runs another year,” he said after the final game on April 12. “And we’ll be out to repeat again next year.”

When asked whether he would consider managing a major league baseball team, Stewart replied, “I guess I’ll stick to umpiring as my baseball career. As Bill Klem said, ‘You can’t beat those hours.’”

A week later, he would be the third base umpire on opening day in Philadelphia as the Dodgers routed the Phillies.

Despite his playoff success, the Black Hawks faltered early in the 1938-1939 season, though there were a few bright moments. One in particular occurred before the opener on Nov. 3, when Chicago Cubs manager Gabby Hartnett presented the Stanley Cup to Stewart in a pregame ceremony. Such pleasant times were few and far between, causing Stewart’s firing less than halfway into the season.

“I don’t think I had it coming,” Stewart said. “I have had no trouble with any of the players and have no complaint or particular alibi.”

Stewart spent the rest of the hockey season as a spectator. The following year, he dusted off his whistle and went back to being a National Hockey League referee.

He remained in the NHL’s officiating ranks until 1941, when he claimed the league “jobbed him” out of a job.

“After 14 years in the league, you’d think they would let me know I was to be dropped,” Stewart told the Boston Globe’s Hy Hurwitz. “It looked to me like I was getting the run around, and after 14 years of faithful service I don’t think it was exactly fair.”

Five years later, he was appointed chief referee of the minor American Hockey League, supervising the circuit’s referees and helping interpret the rules. Stewart only spent one season in that position.

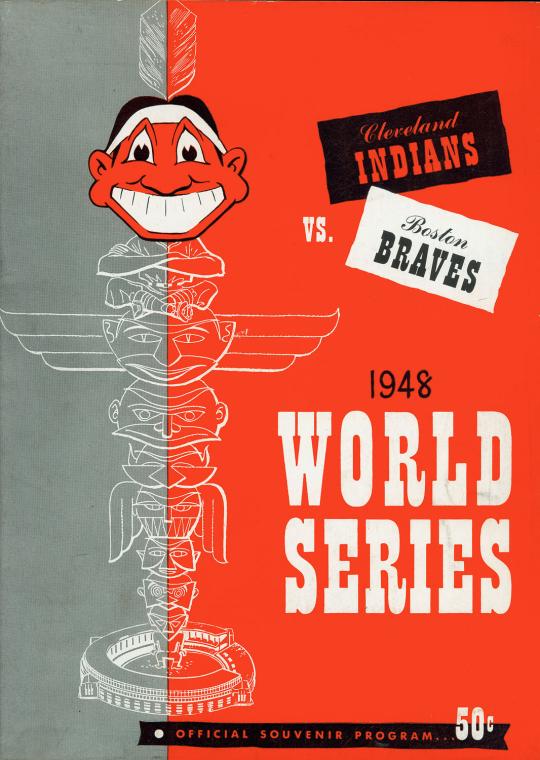

Yet he continued to represent the National League on the field through the 1954 season, garnering assignments in five World Series and four All-Star Games. One of his most controversial calls was in the first game of the 1948 World Series. The second base umpire, he called Braves pinch runner Phil Masi safe on Bob Feller’s pickoff attempt in the eighth inning of a scoreless game. Stewart always maintained Indians shortstop Lou Boudreau tagged him high, though photos suggested otherwise.

Masi ended up coming around to score the game’s only run in a 1-0 Boston win.

Stewart’s retirement from the National League proved almost as controversial as his departure from the NHL. According to the AP, he was strongly disappointed he was not appointed as the league’s supervisor of umpires by National League president Warren Giles.

“I had my heart set on being name supervisor of National League umpires – a position promised me five years ago by Commissioner Ford Frick, when he was NL president,” Stewart claimed. “And since that promise failed to develop, I have decided to quit.”

Stewart said he was offered the position while it was held by the late Bill Klem, and he chose not to accept it while Klem was alive. Giles, upon succeeding Frick, opted to eliminate the position.

This program is from the 1937 World Series, the first World Series that National League umpire Bill Stewart officiated. It is in the Hall of Fame's collection. (National Baseball Hall of Fame)

Share this image:

One of the most controversial calls of Bill Stewart's career came during the 1948 World Series, when he called Boston Braves pinch runner Phil Masi safe on Bob Feller's pickoff attempt at second base in Game 1. Masi went on to score the only run of that game in Boston’s victory, but the Indians eventually won the World Series in six games. (National Baseball Hall of Fame)

Share this image:

In 1956, Stewart was named head coach of the United States national hockey team which would visit Moscow for the world championship tournament the following March. When the Soviets occupied Hungary to tamp down the revolution there, the U.S. State Department pulled the team from the tournament. Yet they were still allowed to travel to Europe that winter for a 25-game exhibition tour.

Even with his new hockey role, Stewart was still active in baseball, scouting for the Cleveland Indians and then the Washington Senators. Seemingly the only thing which could slow him down was the stroke he suffered in Feb. 1964, one which ultimately led to his death at 69 years of age.

Stewart himself would become the patriarch of an officiating family lasting at least four generations. His only child, son Bill, Jr., coached three sports at Boston English High School and officiated the 1954 NCAA hockey tournament as well as the 1971 College World Series. He also refereed college football games. Bill Jr.’s sons Bill III and Paul then went into the family business. Bill III officiated three sports at the collegiate level. Paul played professional hockey in the NHL and the World Hockey Association before eventually becoming a longtime NHL referee – the first American-born referee to officiate in 1,000 games. Another son, Jimmy, briefly umpired amateur baseball games but chose to pursue another career path. Chip McDonald, son of Bill Jr.’s daughter Patricia, officiates college hockey games.

It is certainly possible that the simple whiskbroom in the Hall of Fame’s collection swept more than dirt off of home plate. It also swept the Stewart family into the world of officiating professional and collegiate sports.

Matt Rothenberg is the manager of the Giamatti Research Center at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum