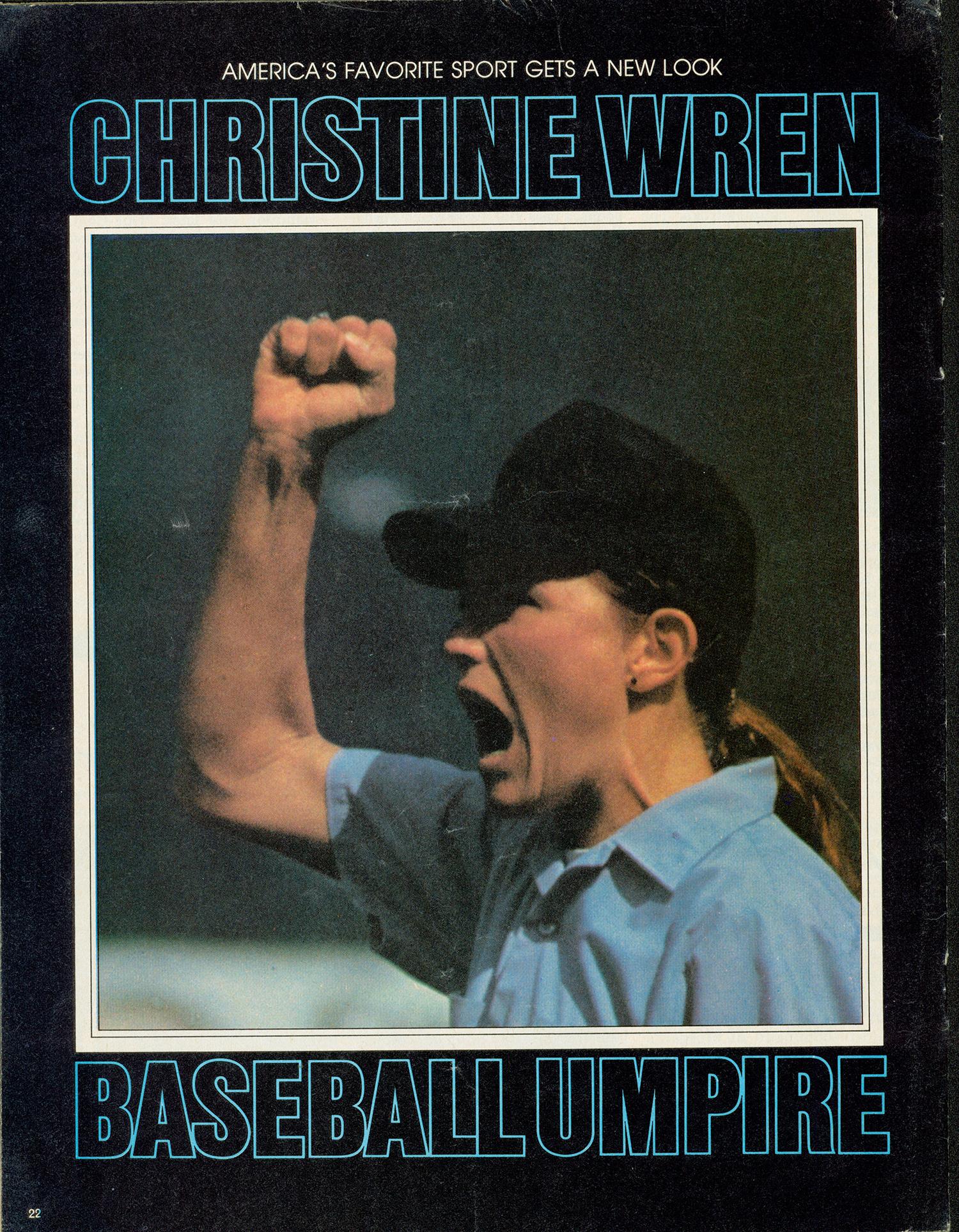

Umpire Unmasked: Christine Wren Opens Up About Her Life As a Baseball Pioneer

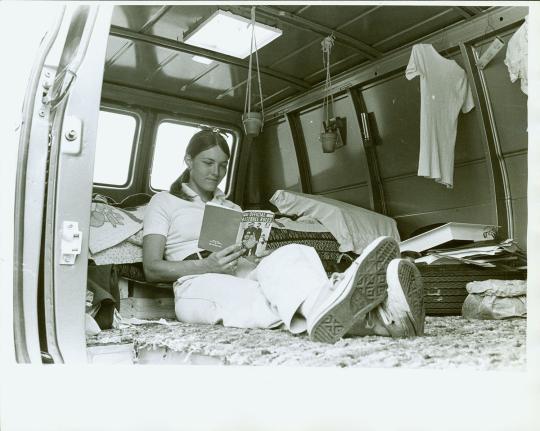

After being sent to the Midwest League, Wren decided it was time to hang up her blue suit. For about 35 years, she avoided all kind of media attention, quietly following baseball as a spectator, while she worked jobs as diverse as truck driving to a school computer technician. But despite her adversity she encountered when umpiring, she never felt ill will toward the game – and to this day, credits baseball for giving her the confidence she needed to work in other female-devoid industries.

“People wanted to know exactly why I left, but I didn’t want to reflect badly on baseball,” Wren says. “I am now able to look back and say ‘I did a good job. I am happy with it.’ It gave me confidence. Once I had been an umpire, I didn’t think there was anything that could stop me. I drove a truck, I got a job working as a computer technician – that got everyone’s heads spinning too.”

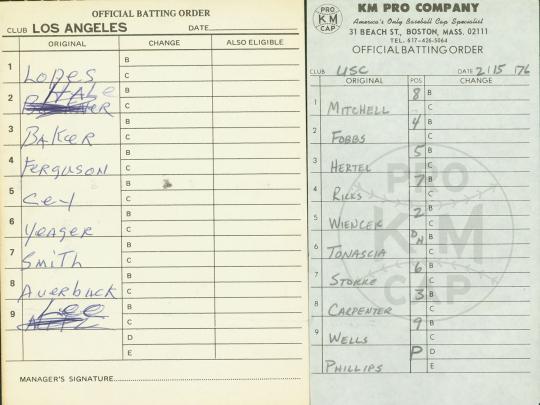

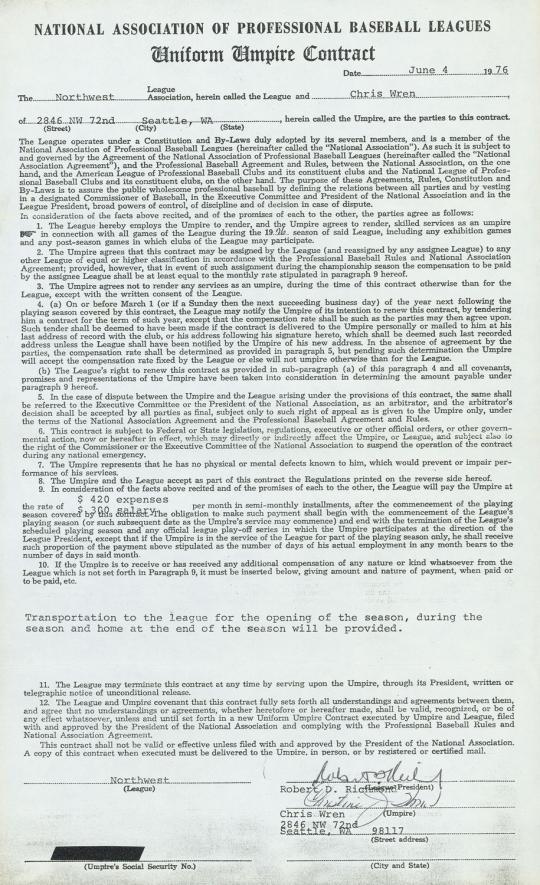

And 35 years after her retirement, she is sharing her history with the world at the National Baseball Hall of Fame, donating multiple scrapbooks, a chest protector and baseballs used in games she worked. While her career as an umpire has come to a close, one thing is for certain: When Wren sees a need for proper officiating, she will not stand by idly.

“When I first left umpiring, I bought a house that sat above a ballpark that I could see – I bought it for that reason,” Wren recalled. “They played Finger League baseball games there, high school level or older. I called a balk from my deck once. I had to run inside – they didn’t know where it came from, or that I was watching. Well, it’s not my fault – they blew it, I didn’t.”

Alex Coffey was the communications specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame