- Home

- Our Stories

- #Shortstops: A Map of the Park

#Shortstops: A Map of the Park

Maps have been used for centuries. Whether hand-drawn on cardboard, printed on paper, or manipulated on a smartphone, maps illustrate roads and landmarks to help us reach our destination.

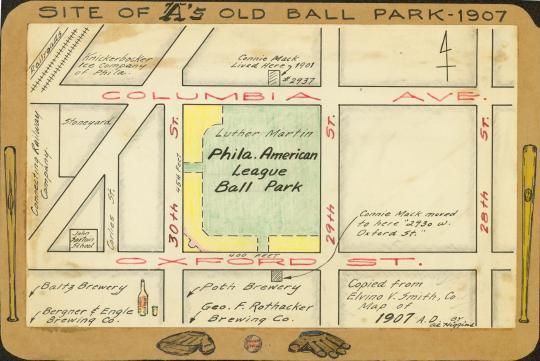

To some, this street map of Columbia Park is no different. To a Philadelphia native, this map tells a deeper story than simply getting you from Point A to Point B. For Philadelphians, this snapshot of four city blocks depicts the glory days of the neighborhood we still know as “Brewerytown,” which served as the backdrop of Philadelphia baseball at the turn of the 20th century.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Nestled in North Philadelphia, less than four miles from Independence Hall, Brewerytown came by its name honestly. In the 1800s, beer production became a popular industry in the Philadelphia area – largely due to the influx of German immigrants in the city – and this popularity led Pennsylvania to being second in barrel production only to New York.

So why brew in Philly? Well, beer is best cold, and if this map was expanded about five blocks to the west, you’d find the Schuylkill River, which was a teeming source of ice. With easy access to ice, Philadelphia breweries were able to establish ice houses and storage cellars, like the Knickerbocker Ice Company in the top left corner, to aid in production. The railroads along 31st street also made it easy for Philadelphia breweries to ship barrels beyond the city.

But Brewerytown was also a baseball town.

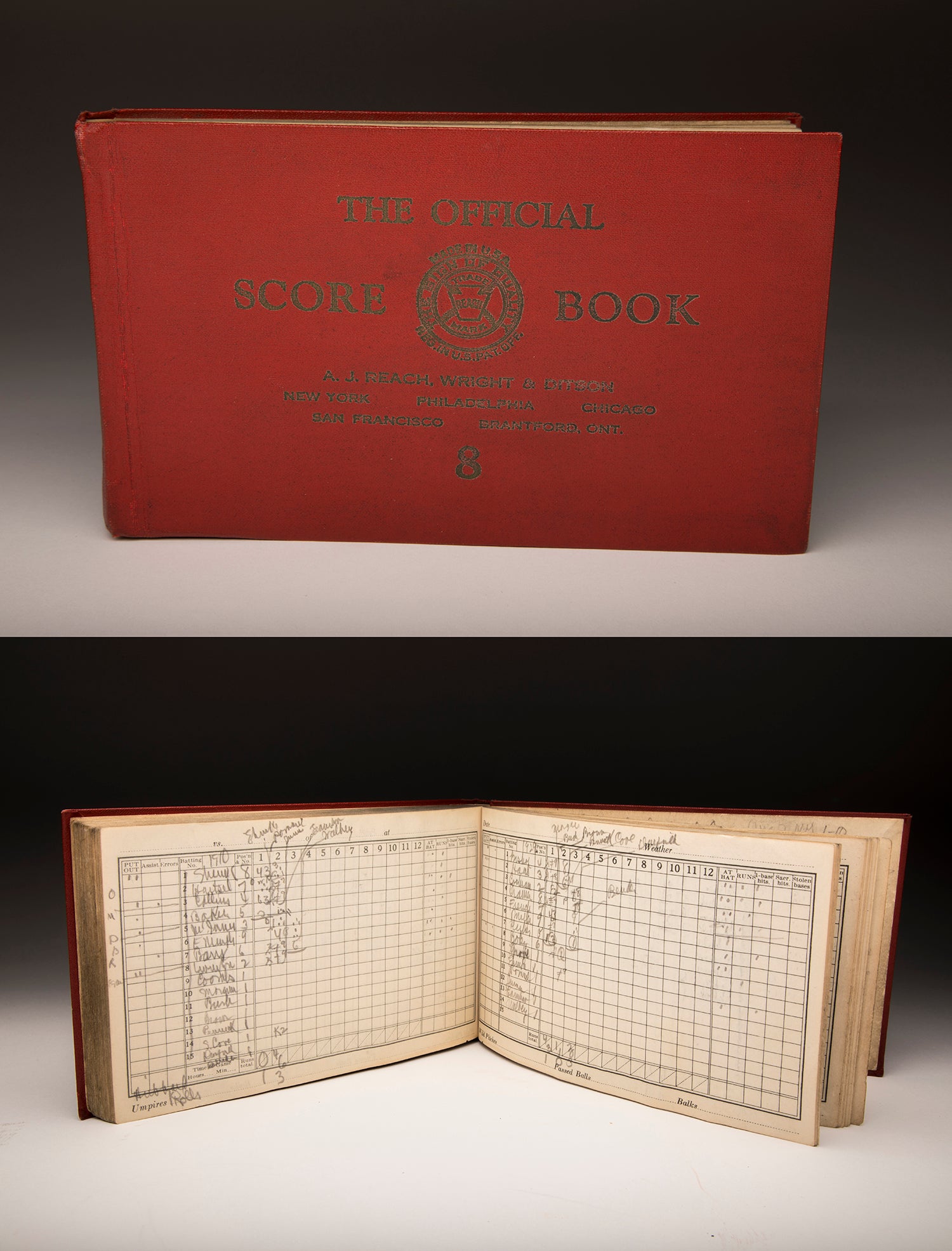

The focal point of this 1907 map is the Philadelphia American League Ball Park, which was called Columbia Park because of the street it occupied. Taking up an entire city block, Columbia Park was the home ballpark of the Philadelphia Athletics from 1901 to 1908. With some of Philly’s first and largest breweries, specifically J. & P. Baltz Brewing Co. and Poth Brewing Company, near the field, Columbia Park had a natural scent of barley and hops. However, the history of baseball and beer started long before 1901.

Prior to the A’s formation under Connie Mack, the National League prohibited alcohol in ballparks. In 1882, the American Association (AA) was created to combat the National League’s rules, from reducing the price of admission to allowing Sunday games and alcohol sales at the ballpark. Since many of the AA team owners were in fact brewery owners and the AA served alcohol in their ballparks, the league earned its nickname “The Beer and Whiskey League” until its end in 1891.

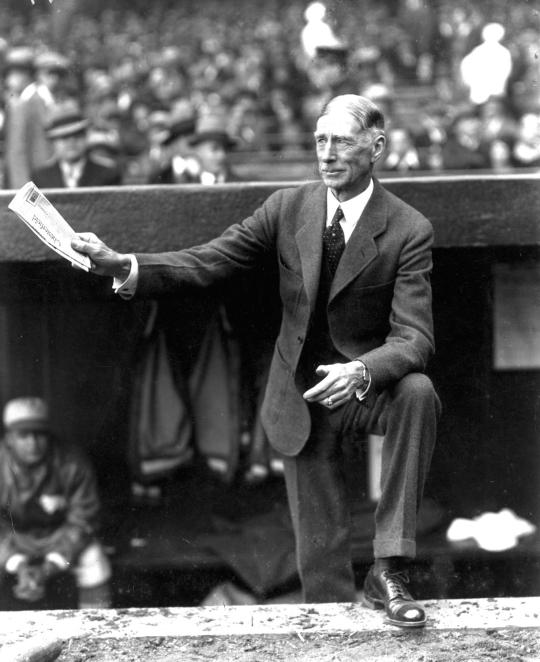

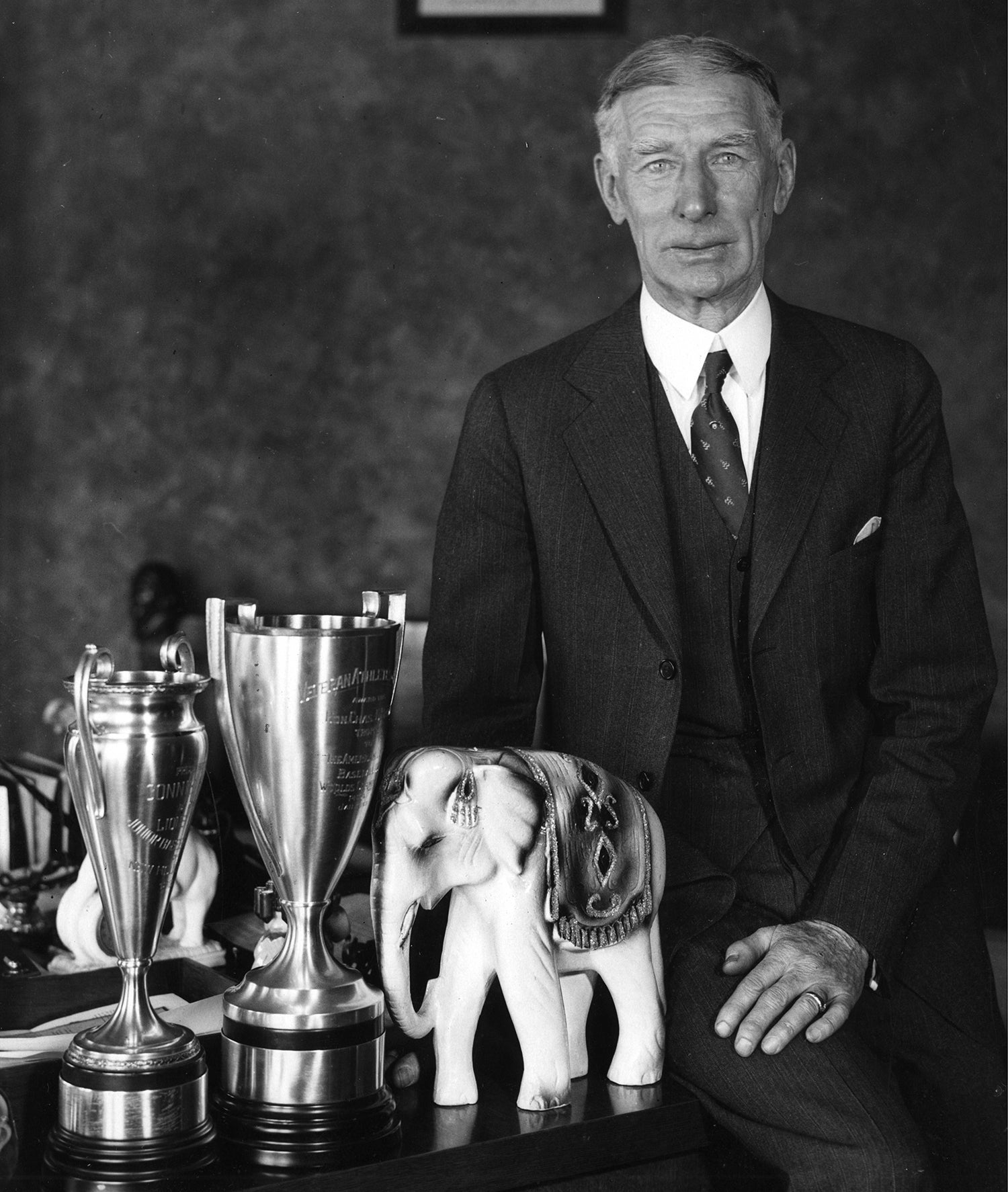

About a decade later, American League founder Ban Johnson asked Connie Mack to establish an AL ball club in Philadelphia despite there already being an NL Philly team, the Phillies. The move ushered in The Grand Old Man of Baseball’s 50-year career with the Athletics and revived the game of baseball in Brewerytown.

As part-owner, treasurer and manager of the A’s, alongside part-owner and president, Ben Shibe, Mack obtained a 10-year lease to a vacant lot on Columbia Ave. between 29th and 30th Streets that became the home of the A’s for eight seasons, with Mack’s personal home never farther than home run or foul territory.

Built by contractor James B. Foster for $35,000, Columbia Park hosted its first game on April 26, 1901. Home plate was in the southwest corner and there were no dugouts. Instead, the players sat on benches near the grandstand, but they did have a clubhouse just for the home team under the stands. Columbia Park was made entirely of wood except for a section of the main entrance which was brick.

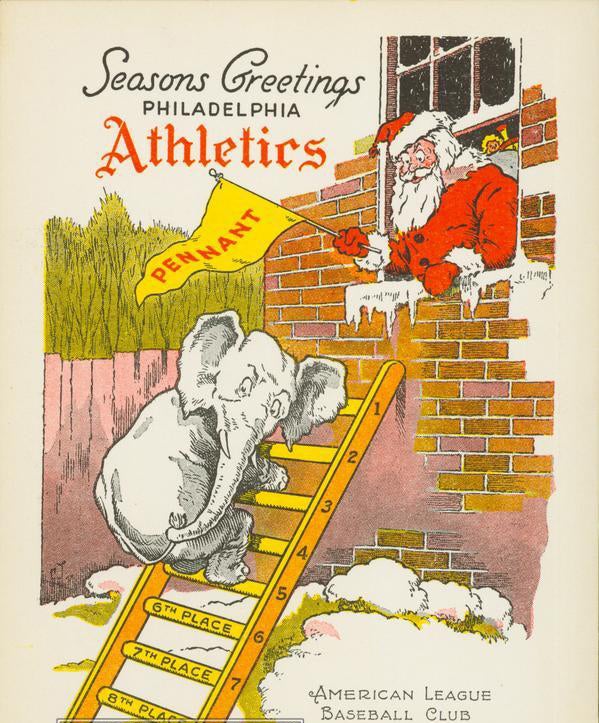

It was the smallest ballpark in the American League which made for high batting averages, on-base percentages, doubles and slugging percentages for all teams. But despite a small park, the A’s knew how to draw a crowd. On Opening Day 1901, Columbia Park had the capacity for 9,500 fans, and by 1905, expansions allowed for 13,600 fans. But the attendance record at the ballpark was almost double its capacity.

In an important late-season game against the White Sox in September 1905, Columbia Park packed in 25,187 fans for a game the Athletics ultimately lost 4-3. But the A’s eventually went on to win the 1905 AL pennant.

Ironically, despite the AL allowing in-park alcohol sales and Columbia Park being in the heart of a brewing hub, Pennsylvania laws prevented ballparks statewide from selling alcohol. But even without the beer, Philadelphia baseball was alive and well.

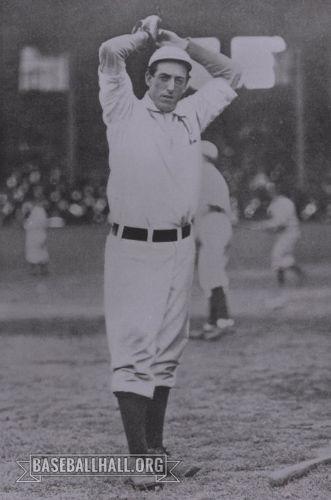

From 1901 to 1908, the Athletics won two AL pennants, one in 1902 and the other in 1905, and hosted one Fall Classic in 1905, losing 4-1 in the World Series against the New York Giants. Through eight seasons at Columbia Park, eight future Hall of Famers played for the Athletics: Nap Lajoie, Eddie Plank, Elmer Flick, Rube Waddell, Chief Bender, Eddie Collins, Jimmy Collins and Home Run Baker. After the 1908 season, the A’s moved to Shibe Park a few miles north of Brewerytown where they would capture seven more AL pennants and five World Series titles under Mack, while Columbia Park was used for the circus and other events.

More than 100 years after this map was drawn, you’d probably get lost if you tried to use it as Brewerytown looks a little different these days. Columbia Park has been replaced by Nicholas Street and Turner Street to make room for residential homes and mini-marts. Connie Mack’s first home is now a vacant lot, but his second on Oxford St. is still an active residence.

Instead of searching for Columbia Avenue on today’s map, look for Cecil B. Moore Avenue – because the street was renamed in honor of a civil rights leader. As for the breweries, most did not survive the Prohibition era, taking the brew out of Brewerytown. Most of the buildings were demolished or converted to other uses, and the railroads that used to carry barrels now carry people as part of public transit bus and trolley routes. The town is primarily residential now with only a handful of breweries and pubs to supply the occasional scent of barley and hops and a few recreational baseball fields to fuel a love of the game.

While this map probably won’t help today’s tourists, it certainly gives a glimpse of where the city of Philadelphia has been.

Jenna Guenther was a the 2019 programming intern in the Hall of Fame’s Frank and Peggy Steele Internship Program for Youth Leadership Development