- Home

- Our Stories

- #Shortstops: Edge of Greatness

#Shortstops: Edge of Greatness

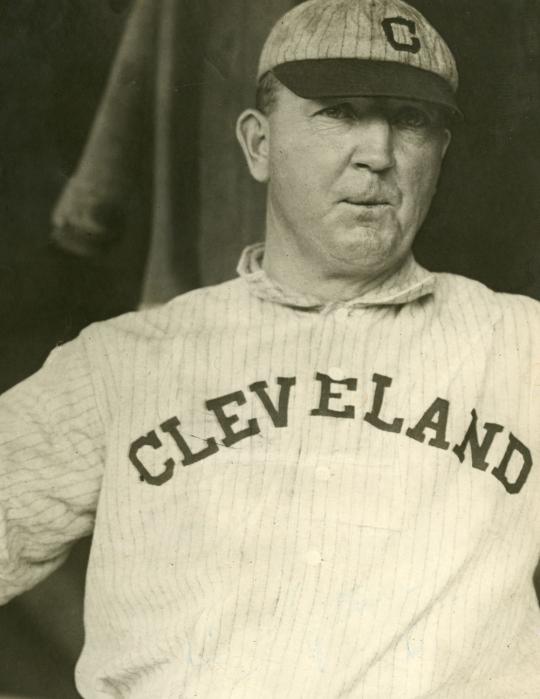

Cy Young dominated two separate eras of play during his legendary 22-year career, leaving career totals that are unlikely ever to be matched.

How did he do it? If the science lies in his DNA, the answer might be found in the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum’s collection.

As the Museum began to seriously concentrate on adding to its collection in the 1950s, William Shelton of Akron, Ohio, came forward with a unique donation offer. Shelton had hosted Young in his home on Sept. 8-9, 1953, when Young was 86 years old.

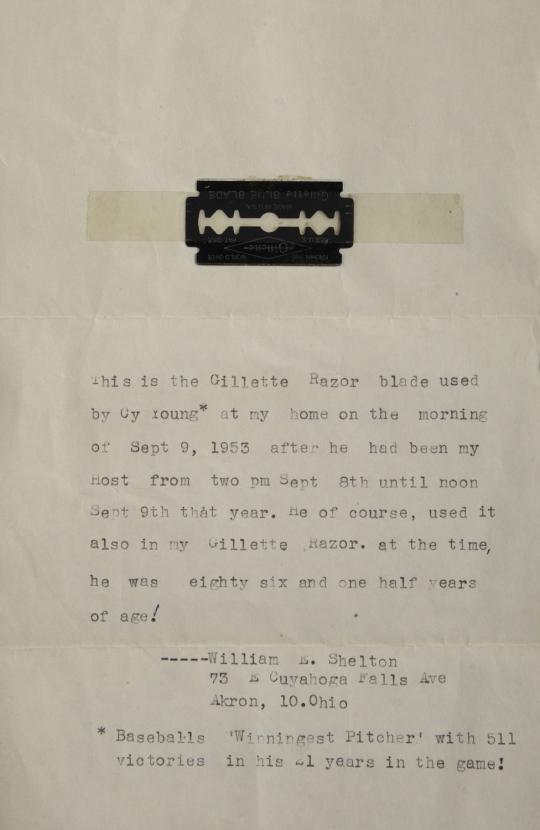

Young passed away on Nov. 4, 1955. A little more than a year later, Shelton sent a letter to the Hall of Fame – with a Gillette razor blade taped to the type-written paper.

This is the Gillette Razor blade used by Cy Young* at my home on the morning of Sept. 9, 1953…

The blade, which could still contain fragments of Young’s skin and hair, was used in Shelton’s razor and is a “Gillette Blue Blade”.

Young, who is buried in Peoli, Ohio (about 75 miles south of Akron), remains the big league leader in career victories (511), games started (815), complete games (749) and innings pitched (7,356). A pitcher starting his career today could pitch 25 years and average 20 victories a season and still not reach Young’s win total.

Young’s career earned-run average of 2.63 doesn’t even crack the Top 50 all-time, which – on the surface – seems strange considering his success and the fact that he pitched in the Dead Ball Era. But Young’s prime seasons came in the National League of the 1890s with the Cleveland Spiders – a decade that saw record-setting run totals with rules that were different than today’s standards.

Future Hall of Famer Billy Hamilton led the NL with 198 runs scored in 1894, for example, and Young’s 3.94 ERA that year ranked fourth in the league.

But after jumping to the rival American League in 1901, Young quickly adjusted to the new low-scoring ways of the time. He would post the best ERA of his career in 1908 at the age of 41 with a mark of 1.26.

Fifty years later, stainless steel that had once smoothed Young’s face found its way to Cooperstown. Then – as now – it was a sharpened edge that had groomed the winningest pitcher in baseball history.

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum