- Home

- Our Stories

- #Shortstops: O’Doul left his mark on the game

#Shortstops: O’Doul left his mark on the game

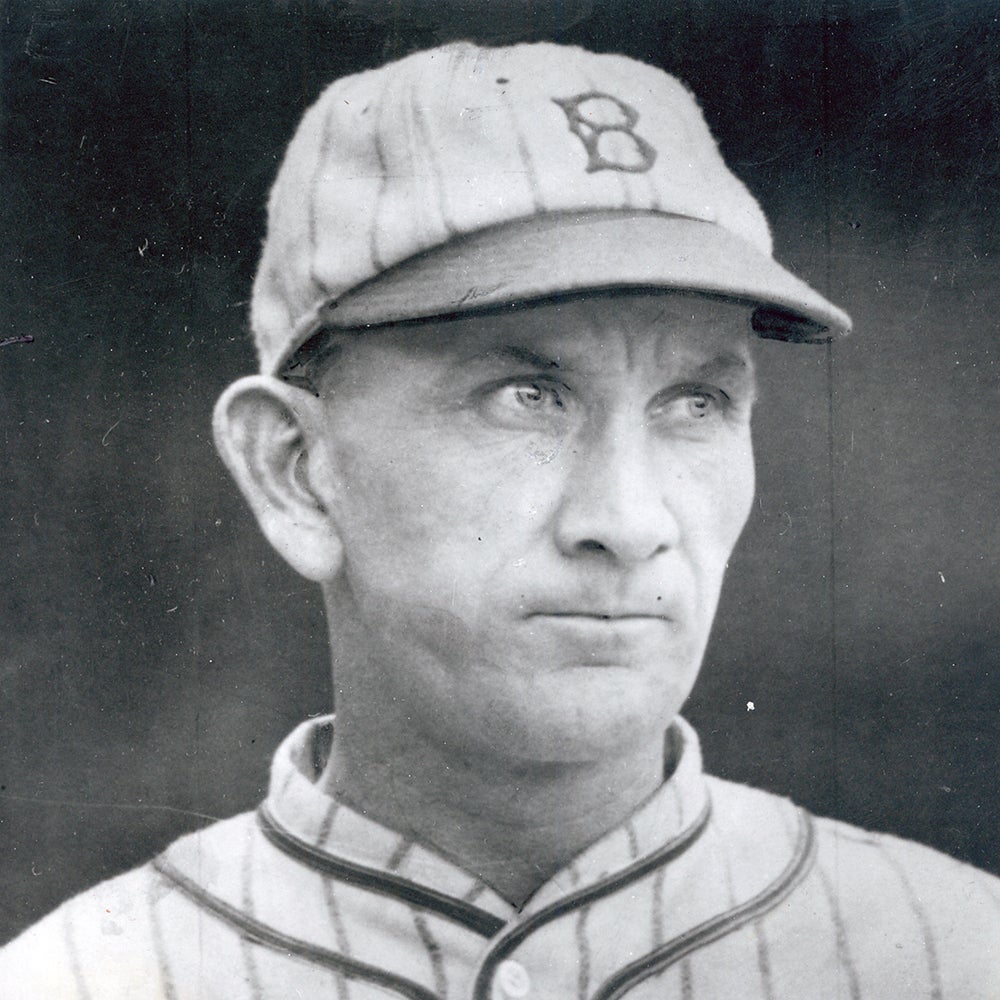

Francis Joseph O’Doul started his baseball career as a pitcher, transitioned into a slugging outfielder and later became one of the game’s great ambassadors.

Lefty O’Doul began his Major League Baseball career as a pitcher for the New York Yankees during the late 1910s and early 1920s. He found limited success as an injury incurred while previously serving with the United States Navy sapped him of his pitching ability. O’Doul was a 26-year-old pitcher with a lame arm and was sent down to the minor leagues as an expendable asset. Despite this major setback, O’Doul vowed to remain a baseball player and sought to hone his outfield and hitting skills.

In four years in the Pacific Coast League, O’Doul walloped pitches for average and power. By 1928, O’Doul returned to Major League Baseball as a 31-year-old outfielder and feared slugger. In 1929, O’Doul set the National League record for hits in a season with 254 which was equaled only once when Bill Terry notched 254 the following season. His .398 batting average that year is the closest a player has come to the .400 mark without reaching it. Furthermore, O’Doul knocked 32 home runs while striking out 19 times in 638 at-bats, or less than three percent of his total at-bats.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

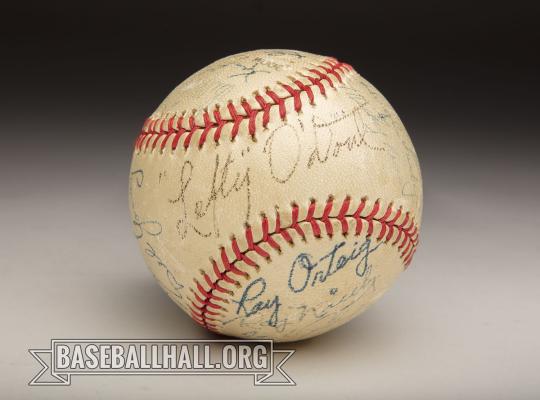

During this period of on-field success, O’Doul had the opportunity to play with many future Hall of Famers while on an overseas tour of Japan in 1931 for exhibition games against university and professional players. According to author Richard Leutzinger, the “all-star team that arrived in Japan in October 1931…[featured] Lou Gehrig, Lefty Grove, Mickey Cochrane, Frankie Frisch, Rabbit Maranville, George Kelly, and Al Simmons, all future Hall of Famers.”

One artifact from this tour in collection at the Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum’s collection is a digitally preserved 16mm silent documentary film that follows the American players as they experience Japanese hospitality and play teams around Japan. A viewer may also catch O’Doul’s sanguine grin as the camera captures the tour. O’Doul’s positive experience during this tour of Japan resulted in him returning the following year, albeit as an instructor.

O’Doul’s 1932 experience was a watershed moment in his career. He enjoyed working with Japanese ballplayers at the universities to improve their skills. In an interview with author Larry Ritter, O’Doul explained his pleasure to mentor the Japanese ballplayers saying, “I like people who you’re not wasting your time on, trying to help them. The American kid knows more than the coach. Teaching Japanese and Americans is like night and day.”

His efforts in Japan earned him a new endearment “O’Dou-San” by Japanese players and spectators. Thereafter, O’Doul continued to visit Japan after the season to play exhibition games and instruct eager Japanese ballplayers.

Lefty O'Doul poses with Joe DiMaggio and a female representative of Japan in 1951. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

In 1934, O’Doul finished his Major League Baseball career with the fourth-highest career batting average of all-time at .349. While on his annual trip to Japan, he was asked why the Japanese teams could not play at the level of competition as their American counterparts.

O’Doul responded, “I tried to tell them that they were playing college baseball only, with boys quitting at 21 or 22, while that’s just when we’re starting.” Hence, O’Doul worked assiduously toward establishing a minor league system for the Japanese players to cultivate and nurture their skills. During this trip, he was offered the manger position for the San Francisco Seals of the Pacific Coast League (PCL) for the 1935 season. In his first year, he witnessed the perfect swing of the 20-year-old phenom Joe DiMaggio, who would lead the Seals to the PCL pennant and then have his rights sold to the New York Yankees.

During the next 10 years, O’Doul’s annual trips to Japan were halted due to geo-political conflicts that would lead to World War II, so O’Doul focused his teaching energies on to his players. At least a dozen stories have been written about O’Doul’s methods to teach young and struggling players to improve. One of the most notable examples was teaching hitters to not lean into a pitch. During batting practice, O’Doul would have the player in question stand in the batter’s box with a rope taut around his waist. When the batter lunged for the pitch, O’Doul would yank the rope hard enough to send the player backwards into the dirt.

A famous example was DiMaggio’s youngest brother, Dom, who suffered through this drill while playing for the Seals. According to Leutzinger, O’Doul showed Dom footage of Joe batting. Dom was astonished to see his brother utilizing the form O’Doul had been instructing. After three seasons of polishing his batting for the Seals, Dom’s contract was purchased by the Boston Red Sox, where he flourished as a hitter over the next decade. Dom credited O’Doul, saying, “He could spot anything you were doing wrong in a minute and show you how to correct it. He was far and away the finest batting instructor that ever put on a baseball uniform.”

After World War II ended, O’Doul returned to Japan in 1949 to lead baseball tours and mentor Japanese players. Japan continued to struggle with the physical and psychological damages caused during the war. According to P.J. Dragseth, this was the “first peacetime cultural exchange of the postwar,” which helped assuage the lingering horrors embedded from the war. In his visit after the 1951 season, O’Doul brought along his famous protégés, Joe and Dom DiMaggio. Within the Hall of Fame collection, there is a photograph of the 1951 tour featuring O’Doul and Joe DiMaggio receiving a bouquet from a Japanese representative.

Although O’Doul was fired by the owner of the San Francisco Seals, Paul I. Fagan, he spent six more years coaching teams in the Pacific Coast League. Despite being past his prime, the passionate manager inserted himself as a pinch-hitter into games to reclaim his old glories. O’Doul recalled his final pinch-hit in an interview with Ritter, “When I was 59, I played in a game at Vancouver. [I] hit a ball that, if I was in my prime I could have walked all around the bases with, but as it was, I managed to waddle to third.”

In the end, the venerable guru retired from baseball activities after the 1957 season, having actively participated in more than 40 straight seasons.

Michael Fishbach was a digital strategy intern in the Hall of Fame’s Frank and Peggy Steele Internship Program for Youth Leadership Development