- Home

- Our Stories

- #Shortstops: California League star’s history told through Museum donation

#Shortstops: California League star’s history told through Museum donation

Back in the 1880s, a teenaged Nick Smith emerged as a minor league phenom, earning platitudes and honors for his bat work and sturdy play at third base. Today, thanks to the generosity of his descendants, three gold medals he received as a result of his stellar play one magical season over a century ago can now be found at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

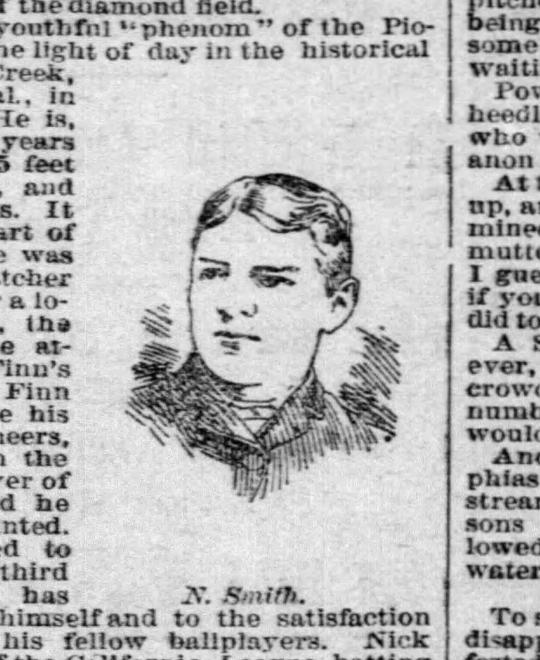

Nicholas Smith, a career minor leaguer who spent over a decade toiling in the bushes, was only 19 when he was plucked off the roster of a local amateur nine by manager Mike Finn and placed on his San Francisco-based California League squad, the Pioneers. The youngster, born in 1868 in the Northern California town of Sutter Creek – famous for its Gold Rush in the 1840s – stood only 5-foot-7 and weighed approximately 170 pounds, but made an immediate impression.

“Nick is a perfect gentleman on and off the diamond, and many a fair one’s heart flutters whenever he takes his position at the bat,” wrote the San Francisco Examiner in November 1887, in a profile of the rookie minor leaguer. “The ‘ahs’ and ‘ohs’ that greet him when he makes a good hit are remarkable for their sweetness of tone.”

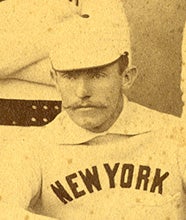

Smith was also receiving high praise from a pair of National League stars at the time, with it being reported that John Montgomery Ward “is looking out for a third baseman for the New Yorks … Ward is now considering the engagement of Nick Smith of the Pioneers,” while Ned Williamson “considers Nick Smith, of the Pioneers, the most promising young player he has ever seen.”

Professional baseball was in its infancy and the burgeoning California League – the West Coast’s first minor league – was during this period a stepping stone to stardom, producing such future big league stalwarts as Clark Griffith, George Van Haltren, Bill Lange, Mike Donlin and Jerry Denny. In 1887, the loop was made up of four squads – two in San Francisco, the Haverlys and Pioneers, Sacramento’s Altas and Oakland’s Greenhood & Morans.

In a season that ran from April to November, Smith not only led the Pioneers to the best record in the league (24-21), but also topped the circuit with a batting average of .307 (54-for-176) in his 43 games played, adding 40 runs scored and 32 stolen bases to his impressive credentials.

“Nick Smith, the third baseman of the Pioneers of the California League,” it read in a September 1888 edition of the Chicago Tribune, “is said to be one of the best in the country.”

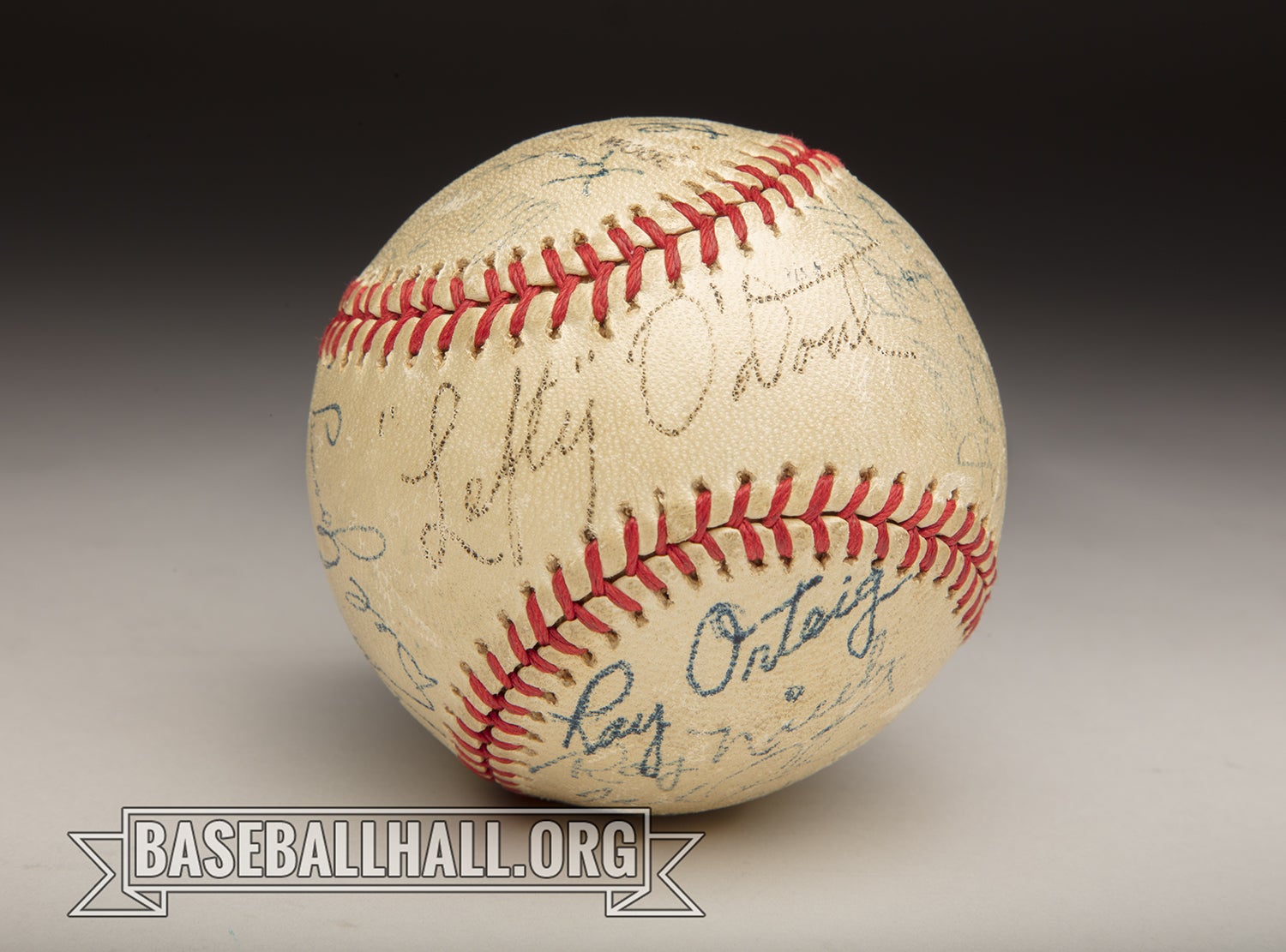

Smith’s burst upon professional baseball scene resulted in a trio of historic gold medals: One for being a member of the California League champion Pioneers, another for topping the circuit in batting, and a third for socking an impressive and memorable home run during the regular season.

In November 1887, the San Francisco Examiner made note of the young ballplayer’s remarkable year: “Nick Smith has three medals, the reward of his honest and efficient work during the past season.”

In an email from his home in California, donor Nick Smith – the great-grandson of the 19th century ballplayer Nick Smith – wrote that it was a family decision to donate the medals to the Hall of Fame.

“We loved the medals, but had little opportunity to showcase them,” Smith explained. “Once I inquired about donating, I contacted my brother and he, too, was all in. We both thought if they could be of use to the Hall of Fame, and that would be the best place for them.

“The toughest decision was by my son. My brother and I had them in our possession for many years. Nicholas had not been able to enjoy them as his own yet. When he learned they might someday be on display at Cooperstown, he felt good about letting them go there.”

According to Smith, he’s been to Cooperstown twice. “Once, in 1962, as a wide-eyed boy and Little League player who only wanted to grow up and become a major league player. I was fortunate enough to return as an adult and lifelong San Francisco Giants fan a few years ago.”

As Nick Smith, the donor, clarified, the ball-playing Nick Smith was where the family name began. It’s legacy continued with the ballplayer’s son, Nicholas G. Smith, the donor’s grandfather, who lived from 1889 to 1949, was followed by the donor’s father, Nicholas J. Smith, who lived from 1923 to 2001, was passed on to the donor, Nicholas E. Smith, who was born 1951, and continues with his son, Nicholas M. Smith, who was born in 1982.

The Hall of Fame has in its permanent collection approximately 175 medals of all different types and origins, from those presented for baseball achievements to those for military service, dating from the 1860s up to the present.

The 1887 California League championship gold medal has it its top an image of two crossed bats with a banner across the top reading “Champion” and a small baseball suspended from the intersection of the two bats. From the chain links at the end of the bats is a crest ringed with laurel leaves that reads “C.B.B.L./1887” around a baseball diamond with four bases, a pitcher’s box, and a small gem inset behind the pitching mound.

Presented to Davis for capturing the 1887 California League batting title, the gold circular medal, 1¼ inches in diameter, has engraved, “Presented to Nick Smith by Lewis Morrison for best Average Batting Cal. B.B. League 1887.”

Morrison was an acclaimed stage actor at the time who announced prior to the start of the 1887 campaign that he would be offering a very handsome gold medal for the best batting average made by any member of the California League that season. The original version of the 18-carat medal had a cross-bar in enameled blue letters the words “The Lewis Morrison Medal,” and suspended from the bar by chains were two miniature crossed baseball bats with a small gold ball in the center, the medal hanging from the bats.

Morrison presented Davis with the medal at San Francisco’s California Theater on Nov. 25, 1887. Appearing in the melodrama “The Main Line,” called in its advertisement “the greatest railroad effects even seen on any stage,” Morrison, at the close of the second act, appeared on stage with the youthful third sacker.

“Ladies and gentlemen, a short time ago I made up my mind to have medal made to be presented to the best baseball player. I did not so this to advertise myself, but out of pure fellowship for the California boys,” is how Morrison addressed the appreciative audience that night. “I don’t play ball myself, but he has faced many a pitcher and knocked many a ball over the fence. I hope he will keep up his hard work and his modesty. I bid him good night, goodbye and good fellowship, as I pin this on his breast in order that he may remember me in after years. You will now agree with me when I say he has again made a three-base strike.”

It was reported that Smith appeared quite embarrassed while Morrison was speaking. Then the pair walked offstage together to great applause.

“Nick, however, had to appear once again, when someone called our ‘Speech!’” the San Francisco Chronicle wrote, “but he simply bowed his acknowledgement and disappeared.”

Davis’ circular home run gold medal, 1¼ inches in diameter, on the front has engraved “To N. Smith for making the first clean home run on the Cal. League B.B. Grounds Sept. 25th 1887. Presented by one of his admirers J.W. S.F. Cal.” The reverse has a baseball diamond in white with four bases, a pitcher’s box, and six black dots on it at the approximate positions of first, second, third and short, and two around home plate.

The home run in question took place at San Francisco’s Haight-street Park in an 8-5 win for Davis’ Pioneers over the G. & M.’s. In the seventh inning, Davis clubbed a two-run homer to the clubhouse for a “clean” home run.

“Family ‘lore’ knows a little about him.” Nick Smith wrote in his email regarding his great-grandfather. “My older cousins and younger brother concur hearing from our parents he was highly skilled (hit for average, hit with power and fielded well), fast and quite handsome.

“His career and life were cut short by an accident. He evidently lost a popup in the sun and was struck in the head by the ball, causing severe, untreatable (at the time) brain damage. He was taken to a ‘sanatorium’ in the Southern California desert.”

Unfortunately for Smith, his life unraveled to a great extent after baseball. In 1901, West Coast newspapers began reporting his strange behavior led him to being committed to a hospital.

He passed away in 1905 at the age of 37. But his legacy will be preserved forever in Cooperstown.

Bill Francis is the senior research and writing specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum