- Home

- Our Stories

- #Shortstops: Real Clowning Around

#Shortstops: Real Clowning Around

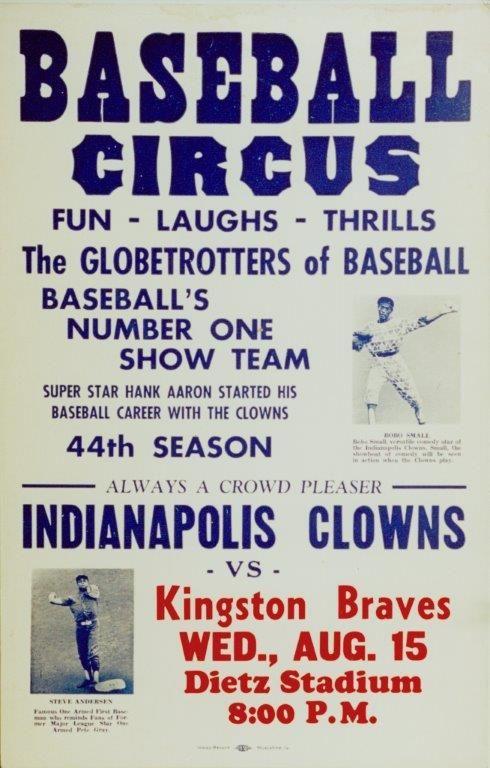

The Indianapolis Clowns were to baseball what the Harlem Globetrotters are to basketball. Through their on-field theatrics, they provided a unique experience for fans of all ages.

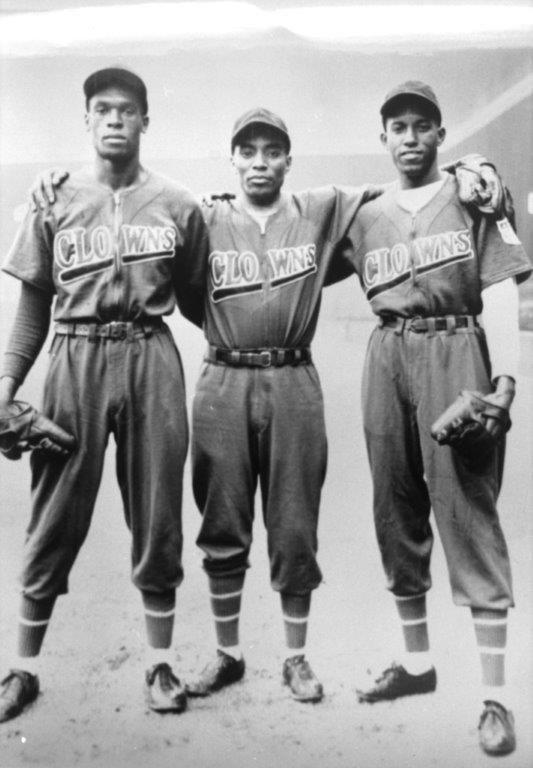

The Clowns were a part of the Negro American League. When the team was created in 1930s, it was originally formed to mimic a minstrel show. This is how the team got the name “clowns” – because the players were always “clowning” during the game. The origins of the team date back circa 1930-1941 as an independent team with no major affiliations.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

This all changed in 1942 when the Clowns officially became part of the Negro Major League. But this partnership proved to be shortlived and the Clowns became affiliated with the Negro American League in 1943. It is important to note that when the team joined the NAL the minstrel style of entertainment was retired but clowning on the field persisted.

The team would continue to be affiliated with the NAL until 1955 before later becoming independent again. The team would call Bush Stadium home from 1946 to 1956. The Clowns had to play talented teams unlike to the Globetrotters, who often played games where the winning outcome was predetermined. But like the Globetrotters, the Clowns placed a premium on entertainment and humor.

The Clowns were an exuberant team with many talented players who had unique personalities. The highly talented team included many famous names over the years, including “King Tut”, “Spec BeBop”, future globetrotters star Goose Tatum, Dero Austin, Ted Richardson, a young Hank Aaron and a colorful character by the name of Ed Hamman.

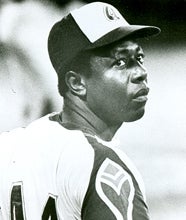

The most famous names out of these players are Aaron and Hamman. Hank Aaron played 26 games for the Clowns in 1951. During that time span, Aaron batted .366 with five home runs, 33 RBI, 41 hits and nine stolen bases. Aaron’s stint with Clowns was very short, as he only played for the team for three months.

Aaron would later play for the Braves when his contract was purchased from the Clowns. He officially was signed by Braves scout, Dewy Briggs, on July 12, 1954. The Clowns thought very highly of Hank Aaron despite his time with the team being short.

Ed Hamman had this to say about Aaron:

“He’s the same Hank who used to wear a Clown uniform. And I like what he said just recently about, even if he broke Babe’s Ruth record, nobody would forget the Babe. Me, I hope he breaks that record. Wouldn’t that be something, from the Clowns to home-run champion of all time.”

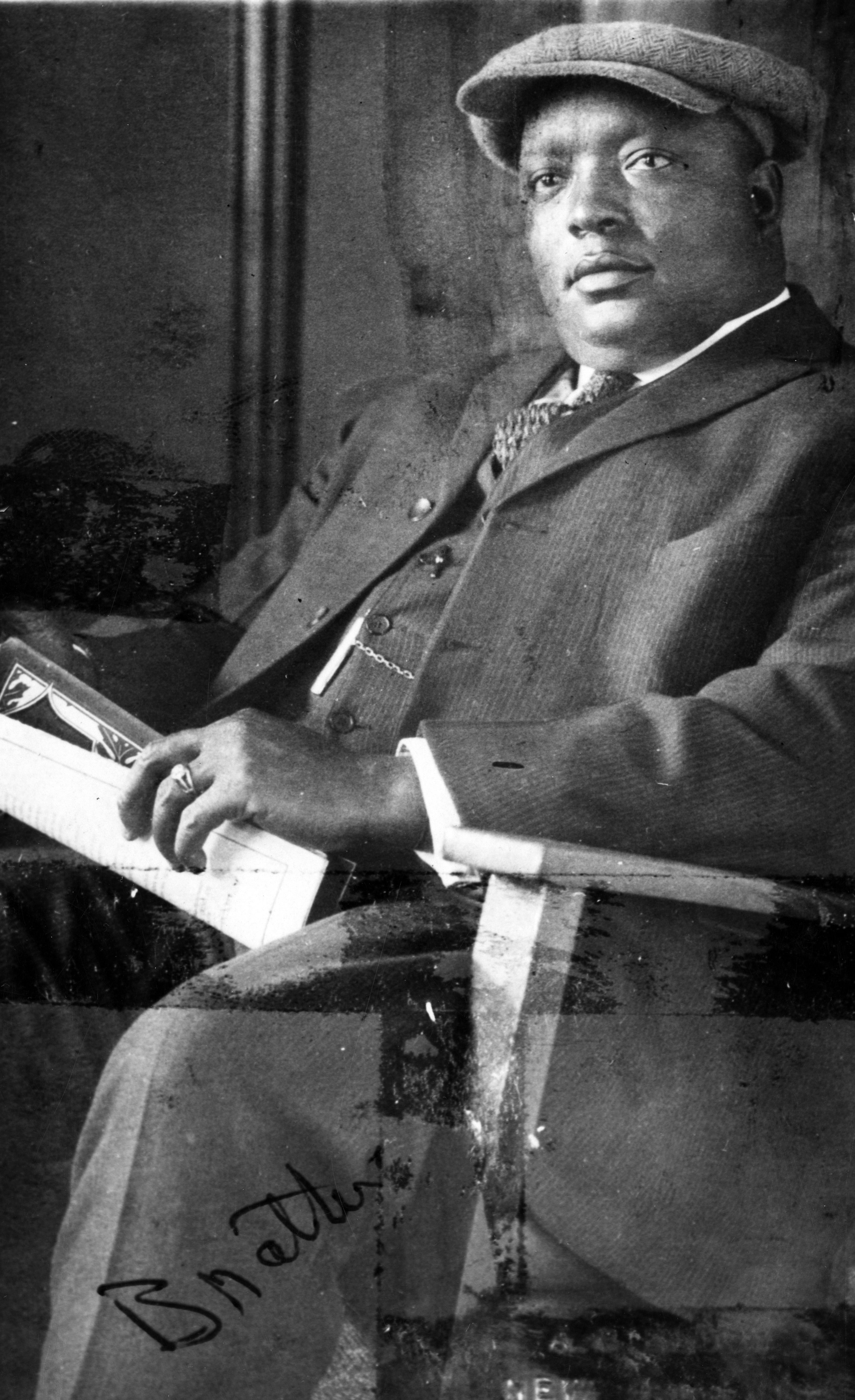

Hamman was a talented ball player but is best remembered for his theatrics on the field and his commitment to fan entertainment. Hamman started his baseball career with the Cuban House of David team in 1927 and 1928. It was during this time when Hamman developed his clown comedy routine.

Hamman would dress up as a clown and would perform in-between innings. By 1933, Hamman had joined forces with Syd Pollock, who would become owner of the Indianapolis Clowns. Hamman would remain dedicated to the Clowns for the remainder of his career and life, performing for the team from 1938 to 1978.

Hamman was also known for his unique pitching style in which he pitched balls behind his back or between his legs to hitters. In 1955, he became part owner of the team and later the sole owner when he bought Syd Pollock’s share in 1968. As the owner, Hamman was also known to joke around on the PA system every game.

The Clowns would spend the majority of their time in the Negro American League trying to find new ways to entertain their fans. One was through the game of “shadow ball”.

Players would mime throwing a ball around in between innings. This was so popular that shadow ball spread to many other Negro League teams.

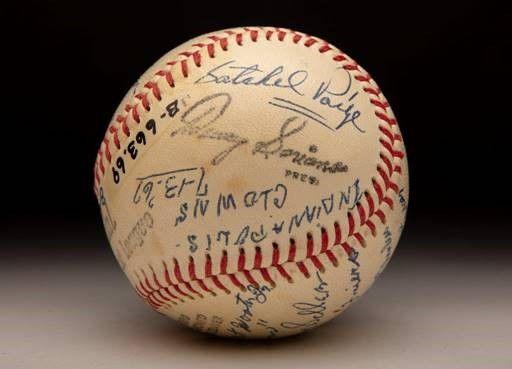

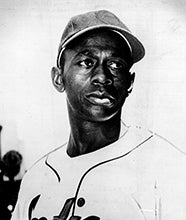

Another Clowns tactic was bringing in established stars. One prime example of this was Hamman’s signing of Satchel Paige to a contract in 1967. Reflective of that signing, the museum’s collection has a 1967 ball signed by Paige and other Clown’s players.

At the time, Paige was believed to be 60 years old and he agreed to pitch one inning per game as a way to attract people to games. Hamman and Paige had a “no show, no dough” agreement. Hamman gave Paige $50 for each game he pitched. It seemed like this agreement worked out well for both parties: While the team held infield practice, Paige would go to a nearby river or stream to fish. When practice was over, another player would come to get Paige, and if there was a large crowd in the beginning of the game he would pitch the first inning. If there was a late-arrival, Paige would pitch later in the game.

Even though Paige was past his prime, Hamman was still impressed with his investment.

“Sixty years old,” Hamman said, “and he could still get ’em out … he threw them dipsy-doodles.”

The team also had little people as players as a way to draw crowds to games.

The Indianapolis Clowns helped create a popular game called "shadow ball", where players would mime throwing a ball around in between innings. (Larry Hogan/National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

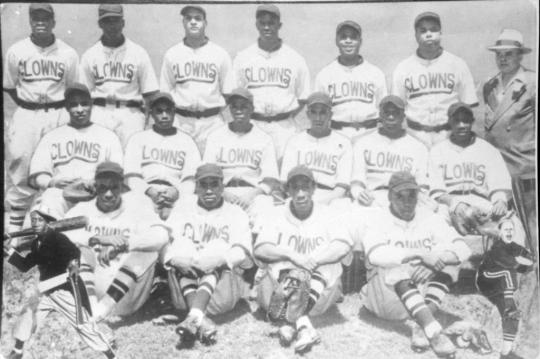

During the Indianapolis Clowns' peak, they played games in the United States, Canada, Cuba, Mexico and Puerto Rico. (Larry Hogan/National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

There are two known little people that played on the team. The first was Spec BeBop who was known to have a rowdy personality. The second was Dero Austin who was also known to be rowdier than BeBop. Despite the supposed problems that Hamman said their drinking habits brought to the team, this duo drew many people to games.

The team also signed women ball players in order to draw fans. These players included Toni Stone, Mamie (Peanut) Johnson, and Connie Morgan.

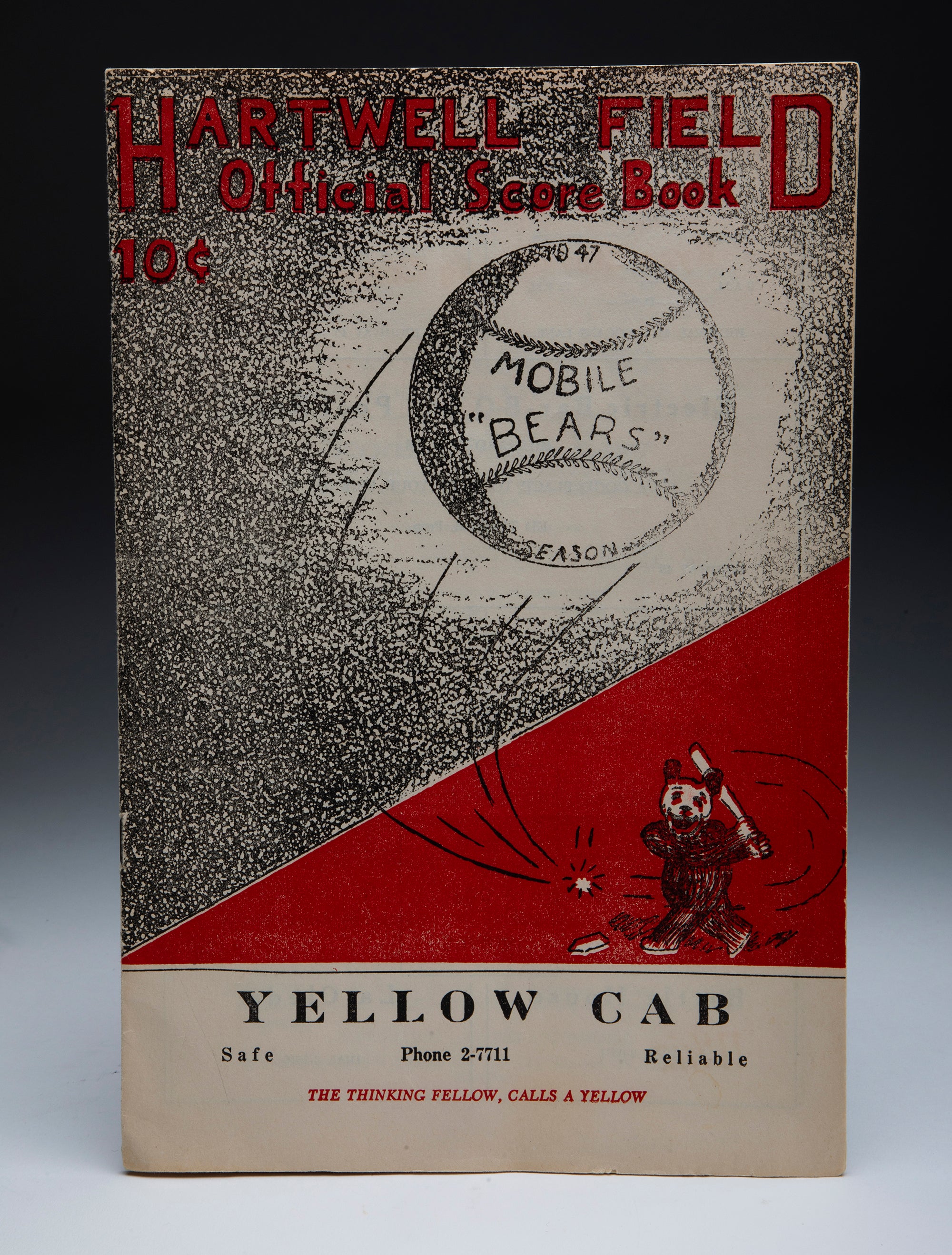

Throughout the years, the Clowns showed they knew how to entertain fans. During their peak, the Clowns played games in the United States, Canada, Cuba, Mexico and Puerto Rico. The team once played in front a record crowd of 41,127 fans in Detroit. The team also published souvenir programs that featured “Laff Books” which had jokes created by the players. In the museum collection there is a 1968 Ed Hamman's Indianapolis Clowns souvenir program signed by Satchel Paige.

But the Clowns were also winners. The team capture Negro American League titles in 1950, 1951, 1952, and 1954. The team’s on-field success and commitment to the fan experience makes them stand out as one of the brilliant teams that baseball has ever seen.

Alexa Brown is the 2022 education intern in the Hall of Fame’s Frank and Peggy Steele Internship Program for Youth Leadership Development