- Home

- Our Stories

- #Shortstops: Sharing the game

#Shortstops: Sharing the game

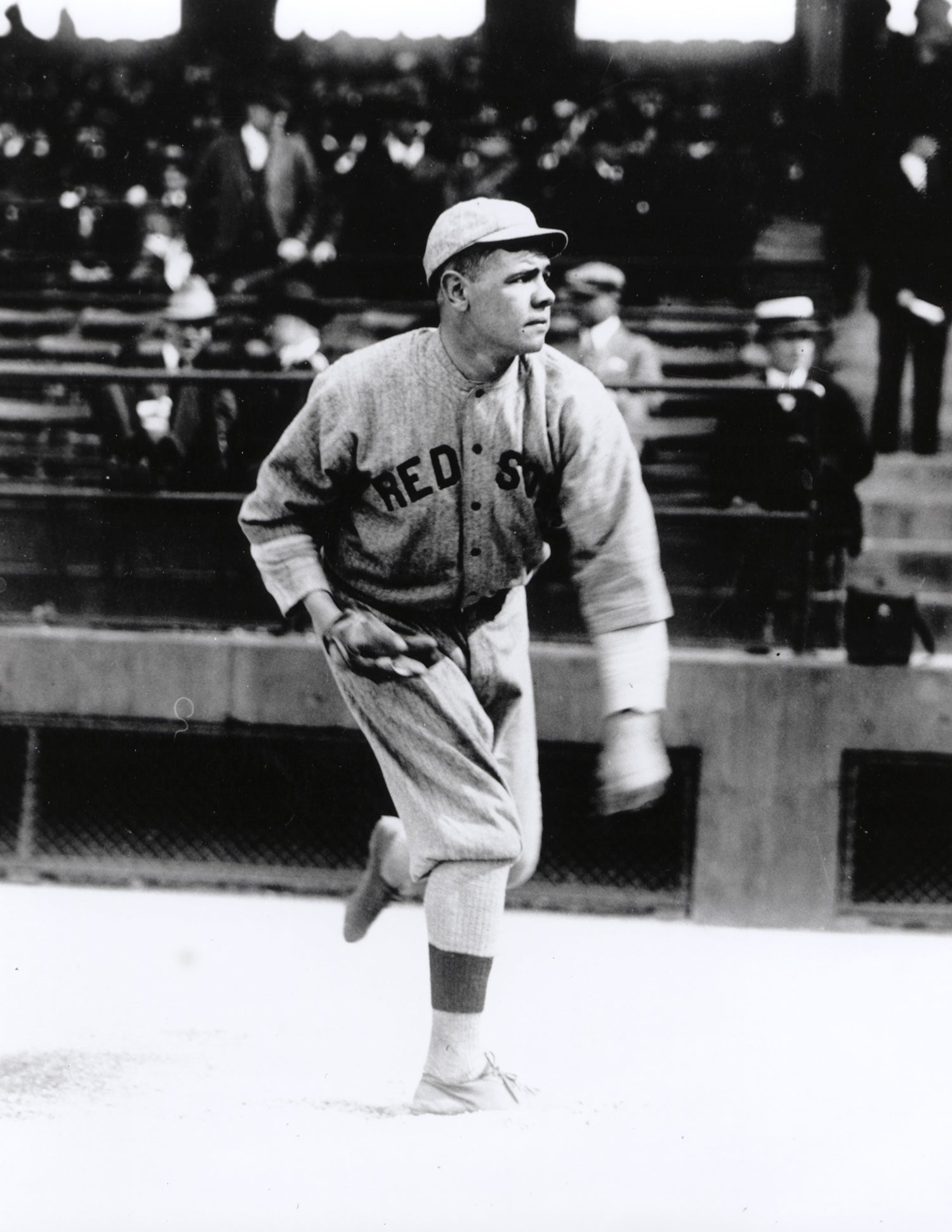

Not every baseball fan has the ability to see the walk-off homerun or the diving catch made in centerfield. But the game transcends visual images.

The roar of the crowd, the crack of the bat, and the feel of the glove among many other sensory experiences give meaning to the game we know and love, particularly for those with impaired vision.

Official Hall of Fame Apparel

Proceeds from online store purchases help support our mission to preserve baseball history. Thank you!

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

The Baltimore Orioles sought to enhance the baseball experience for blind fans, and now Cooperstown is the home of a small piece of history because of the O’s endeavors. On Sept. 18, 2018, the Orioles became the first professional sports team to don Braille jerseys. The team name across the front chest as well as the player’s last name on the back were written using the Braille alphabet.

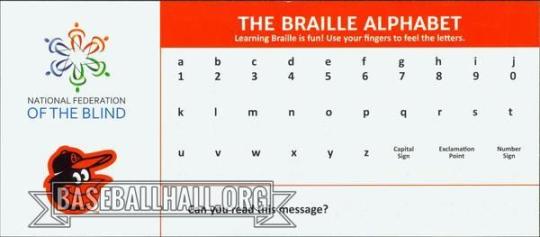

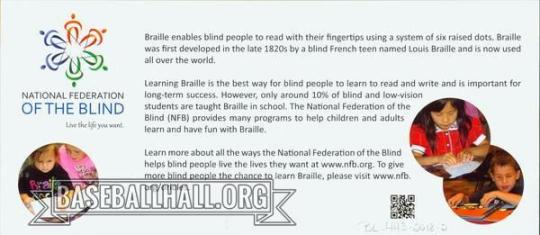

Braille is a tactile reading and writing system commonly used with the visually impaired where people use their ability to touch a system of six raised dots in order to read. Braille was developed by a French teenager named Louis Braille in the 1820s and is now used all over the world as the best way for blind people to learn to read and write.

If you happened to be among the first 15,000 fans in Oriole Park at Camden Yards for this regular season matchup against the Toronto Blue Jays, you received a small rectangular card inside your game program.

At first glance for a sighted person, the program was just a blank piece of paper and the standard alphabet had just been typed on a card. However, somewhere in the crowd, a blind person smiled because a closer look for seeing fans revealed the embossed dots of the Braille alphabet.

These programs and cards were produced by the National Federation of the Blind (NFB), giving blind baseball fans the chance to read the game program – an experience they don’t often get to have – and teach others how to read Braille. The card itself explains the history of Braille and the NFB on one side, and fans of all ages had fun deciphering the “Go Orioles!” message on the other.

Hosting NFB Night at Camden Yards to raise money and awareness for blindness on Sept. 18, 2018, was no coincidence. The event was planned to commemorate the 40th anniversary of the NFB moving its headquarters to Baltimore in 1978.

Originally founded in 1940, the NFB is the largest and oldest nationwide organization of blind Americans, seeking to help blind people live the life they want.

They continually defend the rights of the blind and provide support to blind Americans, recognizing that blindness is not just the inability to see, but rather having sight bad enough such that even with corrective lenses, one must use alternative methods to participate in any activity someone with normal vision is able to do.

For example, the NFB provides programs for blind people to learn Braille since only about 10 percent of blind/low vision students are taught Braille in school.

Carlos Alberto Ibay, a concert pianist who has been blind since birth, performed the National Anthem on Sept. 18, and the NFB President, Mark Riccobono threw out the ceremonial first pitch. Members of the NFB were stationed at the Orioles REACH Community Booth during the game as well.

In the bottom of the first inning, Cedric Mullins produced an undeniable crack of the bat for a leadoff homerun for the O’s.

While the Orioles would go on to record their 108th loss of the season by a score of 6-4, all of the Braille jerseys were autographed, authenticated, and auctioned off to benefit the NFB, with the exception of that of relief pitcher Mychal Givens, which was donated to the Hall of Fame.

Sensory impairment awareness is breaking its way into baseball, as we saw the Myrtle Beach Pelicans organization host a Deaf Awareness night only a month prior to the Orioles NFB Night. Nights like these make the sport of baseball a more inclusive and educational place for all fans.

Now the Hall of Fame will preserve in perpetuity a card that doesn’t appear to say much, but in actuality, is worth a thousand words for its contribution to blind fans living the life they want.

Jenna Guenther was a the 2019 programming intern in the Hall of Fame’s Frank and Peggy Steele Internship Program for Youth Leadership Development