- Home

- Our Stories

- #Shortstops: Slippery elm and the spitball

#Shortstops: Slippery elm and the spitball

A little more than a century ago, the use of slippery elm bark was as ubiquitous as caps and gloves for many big league spitball pitchers.

While the practice was once celebrated – the moist pitch regarded on a par with the fastball and curve – a recent crackdown on foreign substance use on the ball has put the deceptive exercise front and center in today’s game.

In mid-June, Major League Baseball announced – after the results of data collection – that umpires were given new guidance against the use of foreign substances to level the playing field.

As a result of the “sticky” situation, MLB wanted consistent enforcement of Official Baseball Rule 3.01: “No player shall intentionally discolor or damage the ball by rubbing it with soil, rosin, paraffin, licorice, sand-paper, emery-paper or other foreign substance.”

Official Hall of Fame Merchandise

Hall of Fame Members receive 10% off and FREE standard shipping on all Hall of Fame online store purchases.

“I understand there’s a history of foreign substances being used on the ball, but what we are seeing today is objectively far different, with much tackier substances being used more frequently than ever before,” MLB Commissioner Robert D. Manfred Jr. said. “It has become clear that the use of foreign substance has generally morphed from trying to get a better grip on the ball into something else – an unfair competitive advantage that is creating a lack of action and an uneven playing field.”

At the turn of the 20th century, when the spitball was at its heyday, successful practitioners of the moist arts were considered mound masters. The pitch, sometimes referred to in the press as the “saliva shoot,” “damp fling,” “dewy delivery” or “humid hummer” was still legal. But the offering had its detractors.

In a December 1916 interview with the New York Tribune, former pitcher Fred Mitchell, who had recently been named manager of the Chicago Cubs, said he did not believe any foreign substances should be allowed for pitchers on the mound.

“It is quite as unfair, in my opinion, to permit the use of resin, slippery elm and the like to be applied to the ball as it is to roughen the leather surface with emery or sandpaper,” Mitchell said. “Give a pitcher every advantage he may possess in his physical self: he is entitled to as much. But stop the use of artificial aids.”

In a 1919 issue of Baseball Magazine, former Chicago Cubs owner Charles Murphy was adamant in his dislike of the spitball, writing, “The most disgusting sort of delivery, however, is the unsanitary spitball, which should nauseate all decent people. Pitchers chew large slabs of elm bark or other mucilaginous substance to increase the secretions and then practically submerge one side of the ball with the increased flow of saliva. Now any person of intelligence knows that is unsanitary and bad from a hygienic standpoint and should not be tolerated any longer.

“It is not very nice to have to be compelled to inform a crowd of women and young ladies, for instance, that a pitcher is expectorating on the ball, when preparing to deliver it to the batsman. That certainly is not going to make many recruits for the great national game among people of culture and refinement who are searching for outdoor amusement. What would any doctor, who takes only a casual interest in baseball, say if he saw two hurlers slobbering all over the ball on a hot day in July or August and the thing were explained to him. ‘It is time for the health authorities to act,’ he would doubtless explain. Baseball must progress and the sooner this freak stuff is eliminated the more converts there will be for the great sport.”

As Murphy explained in his graphic detail, the use of slippery elm bark helped spitball pitchers facilitate unnatural movement of a ball.

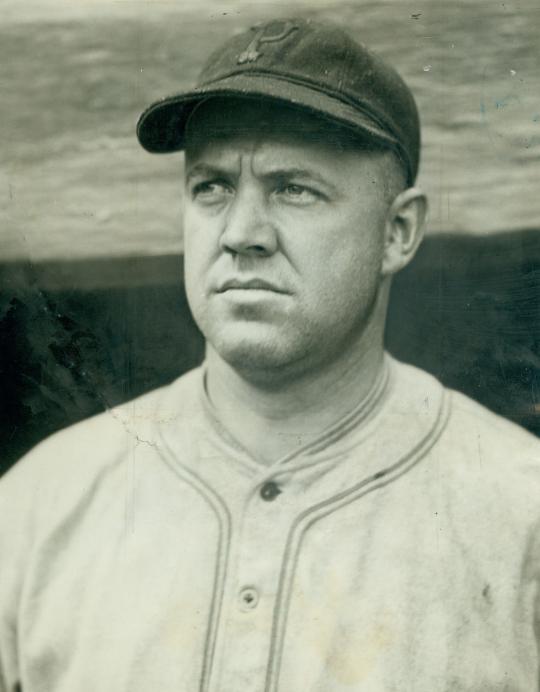

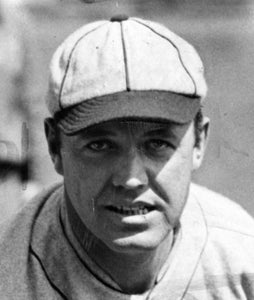

Among the most recognized and successful users of slippery elm bark were Hall of Fame hurlers Ed Walsh and Burleigh Grimes.

Walsh, the Hall of Fame Class of 1946 member whose career ended in 1917 with 195 wins and a 40-win season for the 1908 Chicago White Sox, used slippery elm bark in his mouth to keep up the stock of saliva, then moistened a spot an inch square between the seams of the ball. He then had his thumb clinched tightly lengthwise on the opposite seam and, swinging his arm overhand with terrific force, he threw the ball straight at the plate. “Big Ed” claimed the ball would dart two feet down or out.

“I used to chew slippery elm – the bark, right off the tree,” said Grimes, the 1964 Hall of Fame electee whose 19-year career ended with 270 victories. “Come spring the bark would get nice and loose and you could slice it free without any trouble. What I checked was the fiber from inside, and that's what I put on the ball. The ball would break like hell, away from right-handers and in on lefties.

“You need slippery elm like a motor needs oil, to keep it running smoothly.”

The National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum has in its permanent collection two donations of slippery elm bark, both gifted by Charles Clark, a longtime friend of Grimes.

The most recent donation, from 2013, is a circa 1940s paper package with three pieces of slippery elm inside. A label on the package notes the contents are from The Northwestern Drug Company of Minneapolis, Minn.

Slippery elm, a tree native to the eastern and central United States, acquired its name from the slippery feeling of the inner bark when it is chewed or mixed with water. It’s been reported that Native Americans used the inner bark as a treatment for many conditions. It is still sold today as a possible cure for numerous ailments.

Hall of Fame umpire Billy Evans, in an April 1918 penned column, wrote about the reign of the spitball pitcher from his vantage point on the diamond.

“In order to keep up the proper flow of saliva to moisten the ball it was absolutely necessary that the pitcher chew some substance that would tend to increase the flow of same,” Evans wrote. “Most of the spitball pitchers used a different concoction, although slippery elm enjoyed the most popularity. Others chew licorice, while others stuck to the player’s best friend, tobacco.”

Clarence Mitchell, a spitball artist who won 125 games from 1911 to 1932, was told early in his career that to be a success he had to find a first-class slippery elm tree. “You can get tablets at the drugstore but they’re not as good,” baseball old-timers said. “There is no substitute for slippery elm.”

After months of searching, Mitchell found a small tree on a neighboring farm in Frankin, Neb. The farmer gave the tree to Mitchell.

“The old tree is still producing and the effect of its product is felt in the Coast league this year,” said Mitchell in 1934. “It will never be cut down. As long as there is a spitball pitcher in the game who wants some of that bark, it’ll be there to supply him.”

By 1920, big league baseball began to crack down on those that made the spitball an important part of their pitching arsenal. Originally, 22 spitballers were exempted for only 1920, but a compromise later resulted in 17 being allowed to continue throwing it for the rest of their careers.

Those 17 who benefited were Grimes, Mitchell, Red Faber, Stan Coveleski, Bill Doak, Dick Rudolph, Phil Douglas, Jack Quinn, Dana Fillingim, Ray Fisher, Marv Goodwin, Doc Ayers, Ray Caldwell, Dutch Leonard, Allan Russell, Urban Shocker and Allen Sothoron.

The last of the “grandfathered” spitball pitchers was Grimes, who retired after the 1934 season. His 190 wins during the 1920s led all pitchers – a decade when baseball was transitioning from the dead-ball to live-ball era.

“I use the spitter a lot and I chew slippery elm bark, cut fresh for me by a friend in Ohio, to provide the necessary saliva,” Grimes told a reporter in 1929. “It is nasty stuff and causes my throat to swell.

“Sometimes that durn slippery elm gets me down and I feel so sick I couldn’t beat Oshkosh prep,” said Grimes in 1931. “I don’t dare to take the stuff out of my mouth for what with it tasting like it does and me feeling like I do, I would never get it back in again.”

Grimes’ nickname “Ol’ Stubblebeard” originated because the slippery elm juice irritated his skin enough that he refused to shave on the days he was scheduled to pitch.

After pitching for the Cardinals in Game 5 of the 1930 World Series, one sportswriter reported: “The wad of slippery elm that Grimes used in his mouth made his cheek bulge out like a goiter.”

In a 1971 interview, Grimes claimed to have learned the spitball from a pitcher on a semipro team travelling through his Wisconsin hometown.

“This fellow used slippery elm. So I went out to the woods and got me a batch. It’s a white, fiber-like substance just inside the bark of an elm tree,” he recalled. “I doctored up my fingers and about the second pitch I threw took off. I was on my way.

“Every year when I would report to the big leagues I would take a supply of elm along with me. When I was pitching I would carry it in my glove. That worked all right until I started winning. But then, when I would drop my glove just outside the third base line between innings, the players on the other clubs would come along and give it a kick, losing my slippery elm.”

Reflecting on the spitball era, Los Angeles Dodgers front office executive Fresco Thompson said in a 1966 interview, “Today’s pitcher has to sneak moisture onto the ball and, as a result, he usually can’t get a lot of it. Old-time spitball pitchers chewed tobacco or slippery elm. Chewing slippery elm increased the flow of saliva and at the same time gave the saliva a little more body.

“They really used to load the ball up. As a spitter came toward the plate, you could sometimes see excess saliva flying off. The ball often would still be wet when it was fielded by an infielder. This caused a lot of wild throws.”

Grimes, who passed away at the age of 92 in 1985, told Life magazine the year prior to his death in one of his final interviews the secret of becoming the sport’s most renowned user of slippery elm bark.

“I’d put a piece of bark in my mouth to make the saliva thicker,” he said. “Then I’d release the ball like I was squeezing a watermelon pit. Hell, I can teach anybody to throw one in 10 minutes. What’s hard is controlling the damn thing. Why, some games the spitter was my best pitch, and other days it would break my heart.”

Appropriately, the text on Grimes’ Hall of Fame plaque begins, “One of the great spitball pitchers.”

Bill Francis is the senior research and writing specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum