- Home

- Our Stories

- Switch-pitchers caught a piece of history

Switch-pitchers caught a piece of history

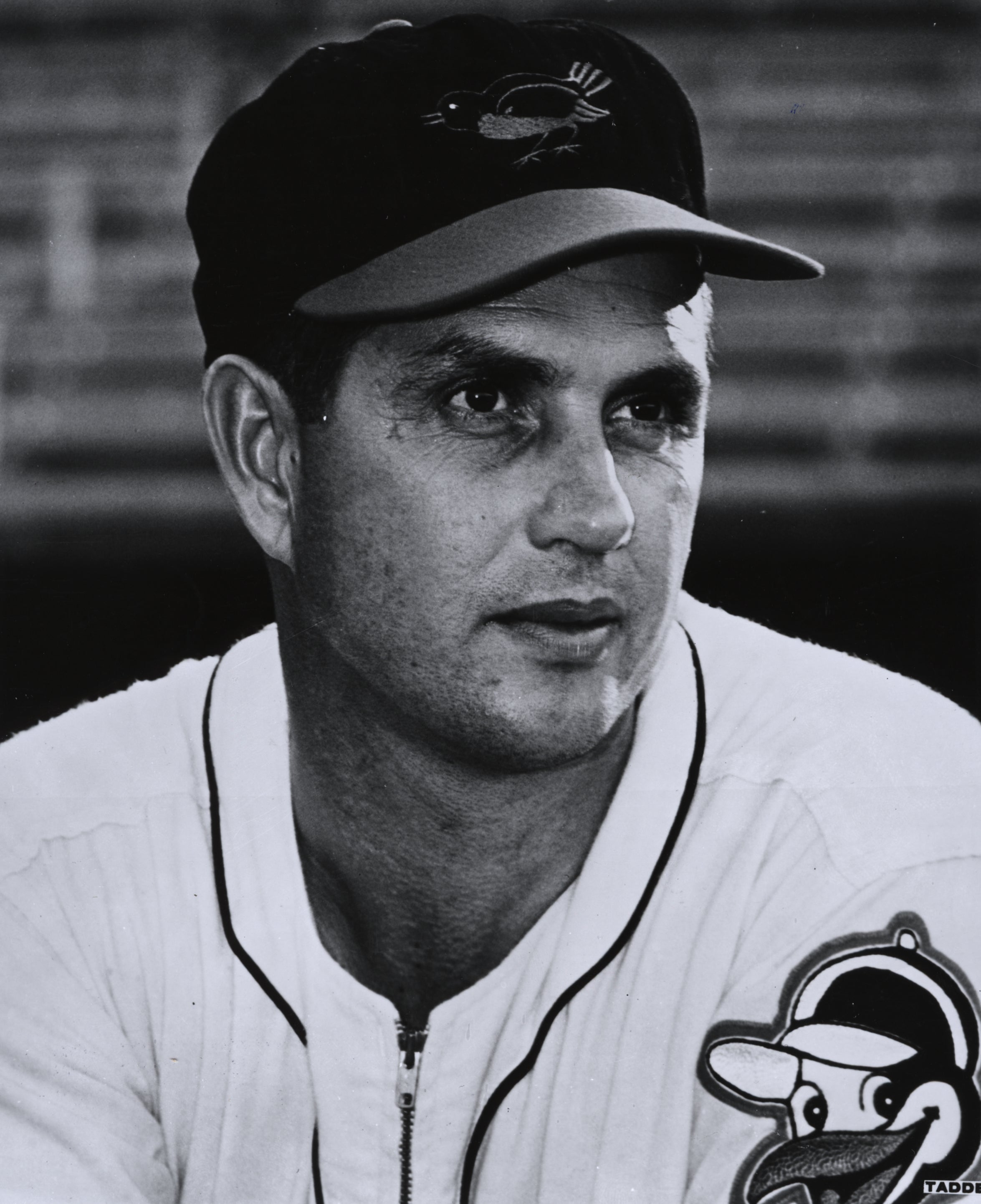

Greg A. Harris was the epitome of a journeyman pitcher, a guy who could start, relieve, eat innings, anything a team needed along the way in his eight major league stops in 15 seasons.

He is also among the less than half-dozen switch-pitchers in big league history.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

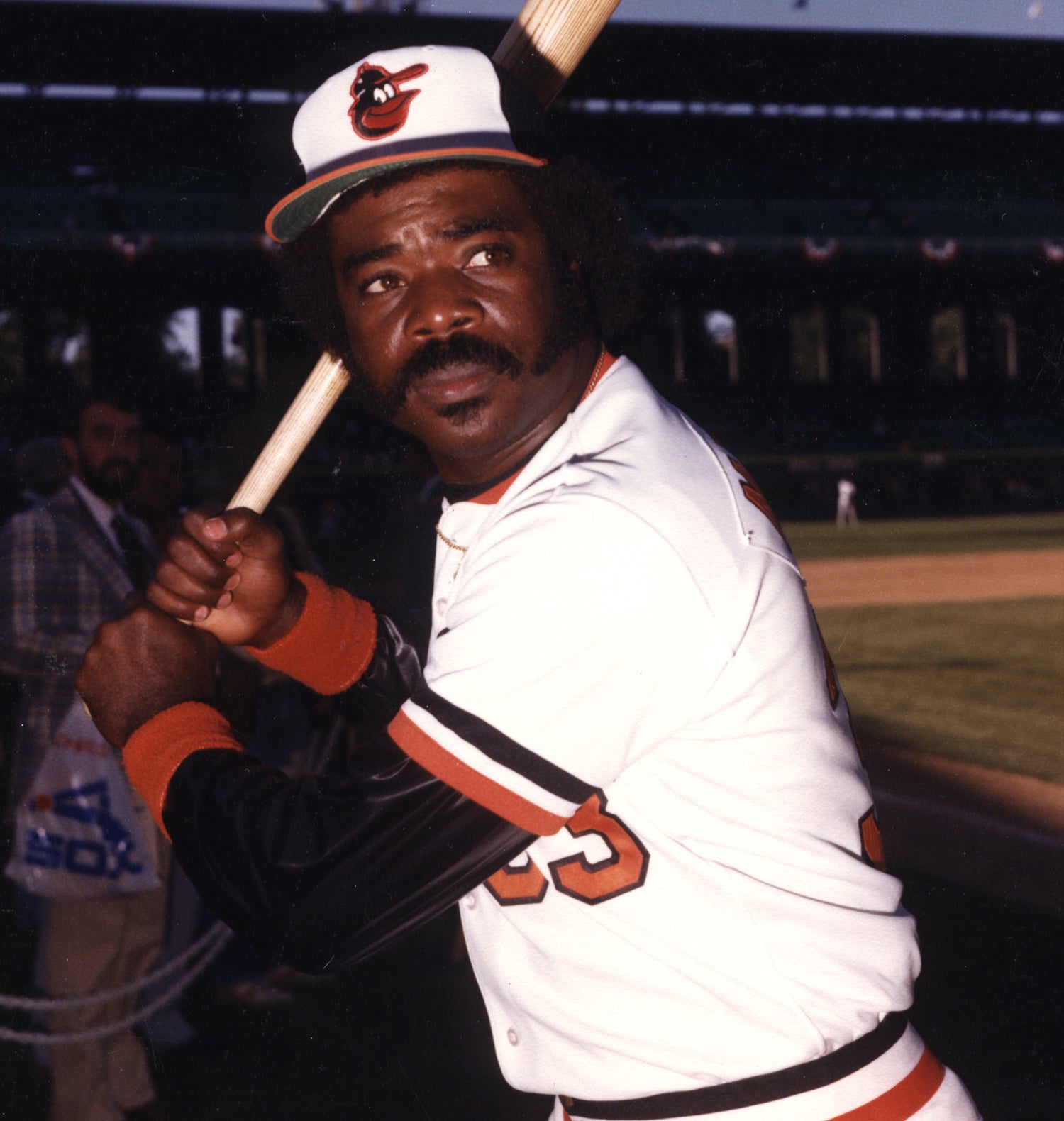

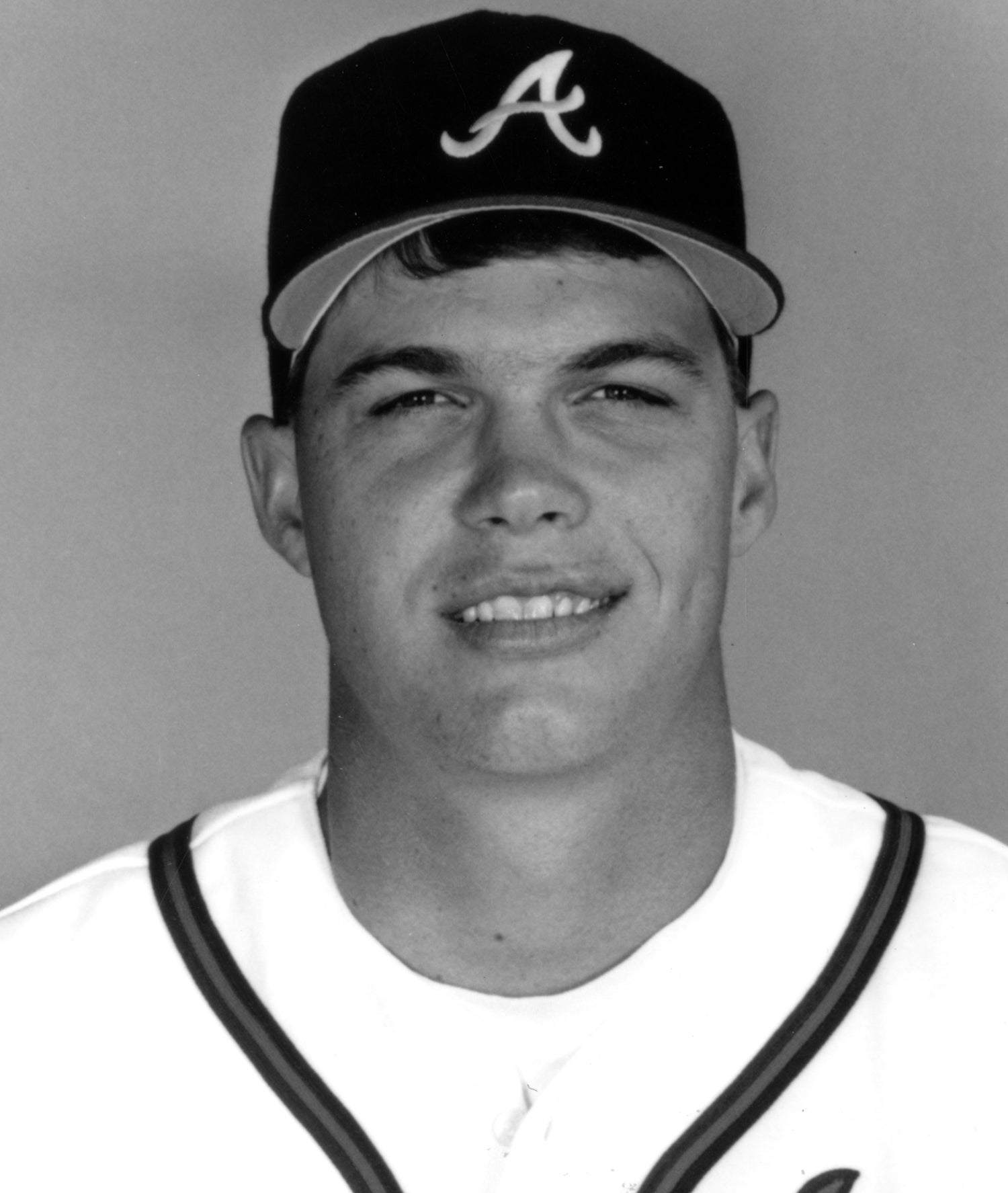

While baseball has a long history of switch-hitters, including such legendary figures as Mickey Mantle, Eddie Murray and Chipper Jones, the act of pitching in a game both right-handed and left-handed had been extremely limited.

With an appearance as a switch-pitcher in 1995, Harris – and his glove – became a part of history.

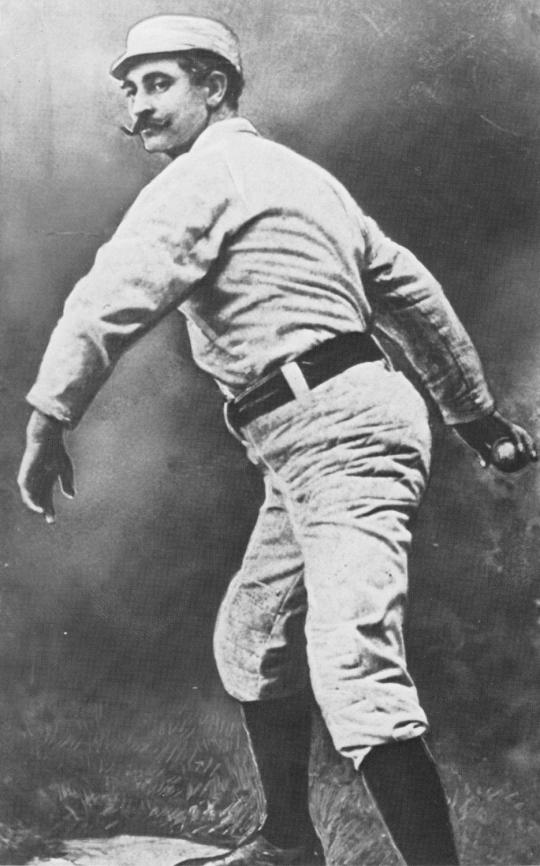

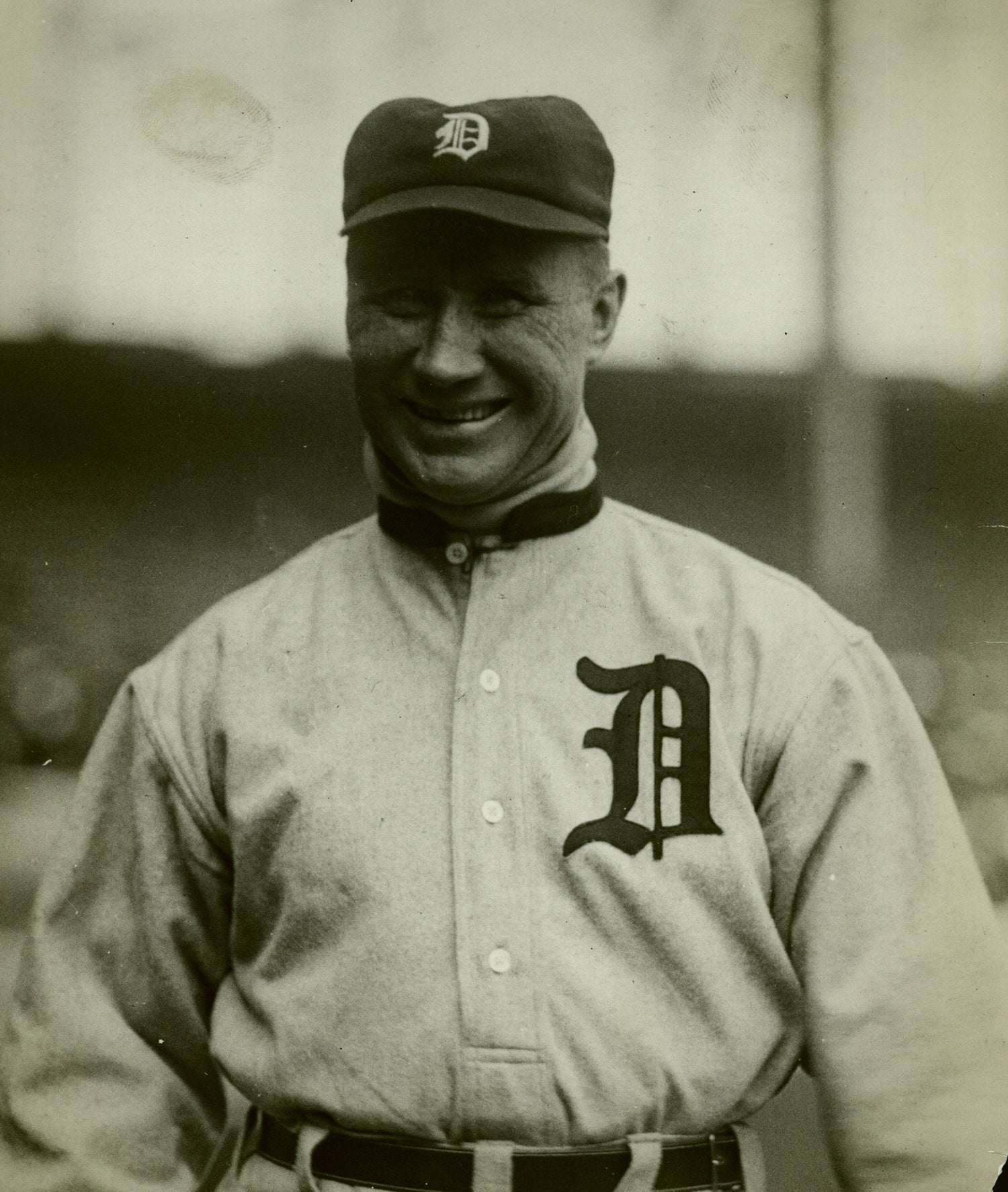

Current research claims Tony Mullane, on July 18, 1882, as the first big league pitcher to toss with both hands. In only his second big-league season, the natural righty, pitching for the American Association’s Louisville Eclipse, started throwing as a southpaw in the fourth inning against the Baltimore Orioles.

Mullane was one of the most famous pitchers of his time. During a 13-year big league career spent during the 1880s and 1890s, he compiled a 284-220 record, including winning 30 or more games in each of his first five full big league seasons. A sore right arm led to the eventual use of his left.

According to Hall of Fame shortstop Hughie Jennings, a mid-1890s teammate of Mullane’s, he was once told by the pitcher that it was easy to throw with either arm.

“The next day we were playing Chicago and late in the game our pitcher was knocked out,” Jennings said. “Manager [Ned] Hanlon told Mullane to relieve him and before he started for the box Mullane told us that he was about to give a demonstration of pitching with the left.

“Mullane picked a bad spot for his demonstration. The batter was Bill Lange, and Bill was by no means a slouch. The catcher signed for a curveball and Mullane wound up and delivered the curve with his left, but Lange made a fast one out of it. I don’t think I ever saw a ball travel faster over the center field fence than the one Lange hit off Mullane’s left-handed curve. Mullane ceased being an ambidextrous pitcher then and there.”

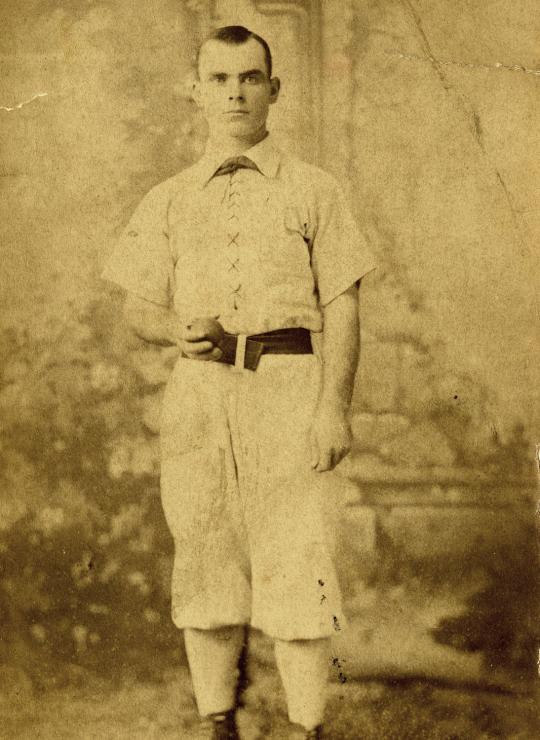

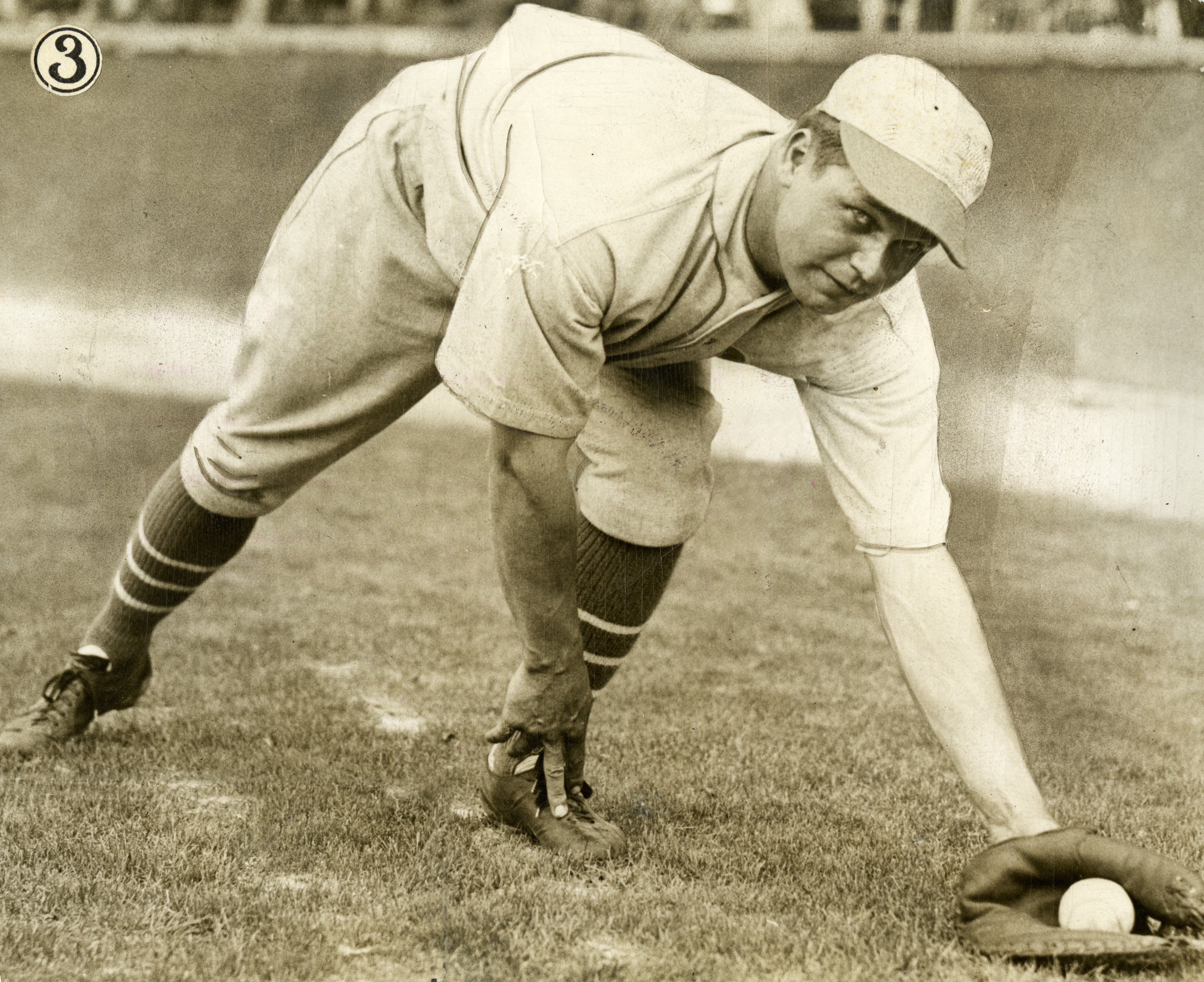

Other 19th century pitchers to have thrown with both hands in game action include Larry Corcoran, who averaged 34 wins per season from 1880-84 with the National League’s Chicago White Stockings, and Elton “Icebox” Chamberlain, who ended his big league career in 1896 with a 157-120 record. There have also been disputed reports that George Wheeler turned the trick with the Philadelphia Phillies in the 1890s.

In the 21st century, Pat Venditte joined the switch-pitching club in 2015 as a member of the Oakland Athletics.

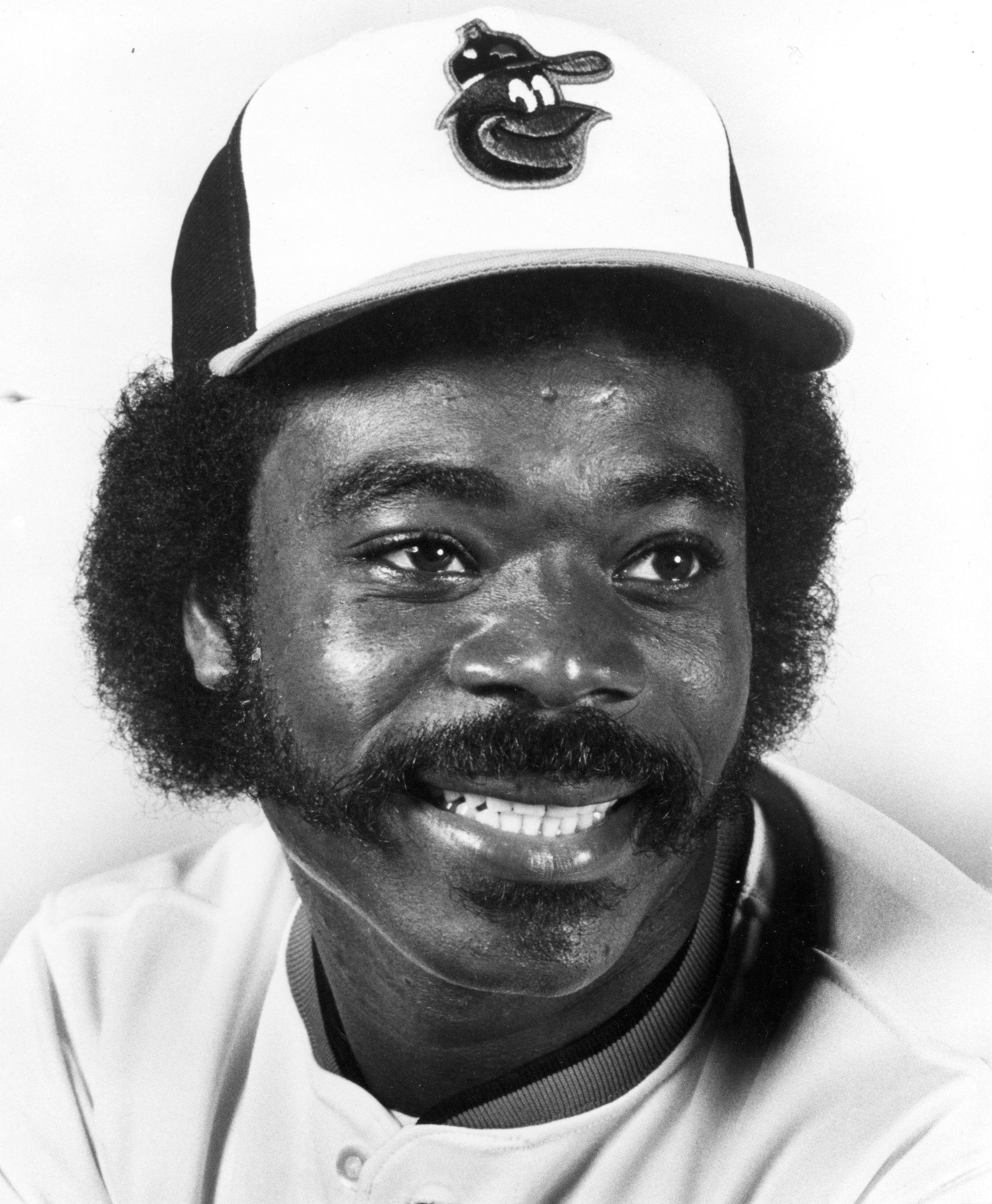

And in between, Greg Allen Harris (not to be confused with Greg Wade Harris, a fellow pitcher of the same era), after pitching exclusively right-handed during the first 14 big league seasons, faced batters throwing lefty in what proved to be the penultimate game of his career.

A member of the Montreal Expos at the time, Harris entered in the ninth inning of his team’s Sept. 28, 1995 game against the visiting Cincinnati Reds with his team trailing 9-3. Pitching right-handed, he retired Reggie Sanders on a grounder to short, then switched to throw left-handed to Hal Morris. After his first pitch sailed to the backstop, he walked Morris with three more balls, but retired left-handed hitting Eddie Taubensee, again pitching left-handed, on a catcher to first groundout. Going back to right-handed, he retired Bret Boone on a ground ball, pitcher to first, to end the inning.

Only weeks after his memorable accomplishment, Harris, accompanied by his wife and parents, travelled to Cooperstown to donate his specially designed six-finger glove and a baseball from the historic occasion to the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

According to Harris, the idea of pitching with both hands came while a member of the 1986 Rangers.

“[Manager] Bobby Valentine and [pitching coach] Tommy House came up with the idea of me pitching left-handed. At that time we only had five right-handed pitchers in the bullpen and no left-handers,” said Harris to a Grandstand Theater audience at the Hall of Fame. “By the end of the 1986 season, there were three tests I had to pass to be able to pitch left-handed in a game: I had to throw 80 miles per hour, I had to have a curveball, and I had to throw 25 of 30 strikes. I started Aug. 1 of 1986 and by mid-September I mastered all three skills and was ready to pitch.

“In 1986, we were in contention with the Angels, so the opportunity never came around. The next year, Bobby Valentine found every left-hander he could find in the organization and brought them to Spring Training, so I kind of got the hint that that was maybe my last chance of doing it. For the last 10 years, my dream was for somebody to finally give me the opportunity to throw in a game.”

When the 39-year-old Harris finally got his chance, he called it probably the most nervous time of his life.

“I realized this was happening and this was the opportunity I was waiting for,” Harris said. “The fans went crazy because they saw me warmup left-handed in the bullpen. After the first out I turned around towards second and kind of snuck the glove around and the fans went crazy again. Thank goodness Morris wasn’t a right-handed hitter or he probably would have ended up in the hospital. The most fortunate thing was I was able to face another lefty (Taubensee) and actually got somebody out.

“I didn’t hit anybody, I didn’t hurt anybody, and it didn’t ruin the integrity of the game. It came out very professional and that was the way I wanted it, to prove that it was not a joke, that it was something I could do.”

Harris had been using his six-fingered glove, specially designed by Mizuno, with two thumbs and a wide, pie-shaped pocket, since 1986.

According to reports at the time, on June 15, 1989, Harris, then a member of the Phillies, entered a game against the Pirates in the bottom of the fifth and Pittsburgh outfielder Andy Van Slyke was on third base. As Harris walked to the mound, Van Slyke said, “Why does he have a glove like that,” to third base coach Gene Lamont.

Phillies third baseman Randy Ready, who overheard the question, replied, “Because he’s amphibious.” To which Van Slyke asked, “Does that mean he can throw underwater?”

Today, that glove is in the permanent collection of the Hall of Fame.

“It’s something I always wanted to do, and it’s gotten me to the Hall of Fame. This was the only way I’m going to get there – from the left side and not the right side,” Harris said in 1995. “I’m grateful that the Hall does recognize unique achievements and that I had the opportunity to be a pioneer of sorts. My left arm had to get me in because my right arm never would have.”

Bill Francis is the senior research and writing specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum