- Home

- Our Stories

- Wolff Wednesdays: Talking with Teddy Ballgame

Wolff Wednesdays: Talking with Teddy Ballgame

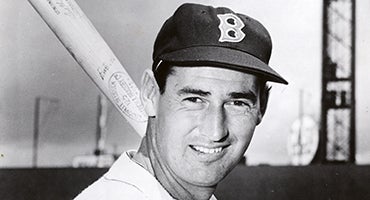

Bob Wolff made a bold statement to television viewers as he introduced a taped piece with his guest Ted Williams.

“I believe that this interview, which was made a couple of seasons back during the latter part of the year, is the most revealing study of the big slugger which has been put on film,” promised the Washington Senators broadcaster.

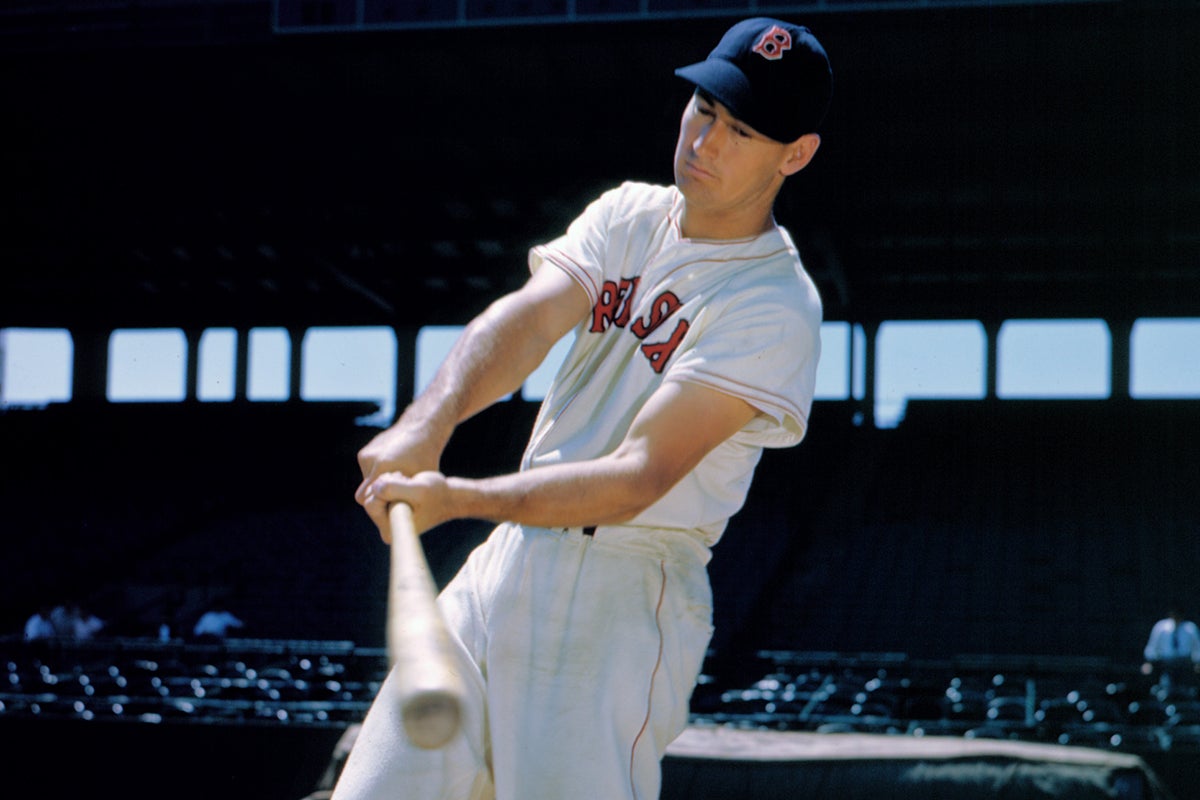

Just as he did throughout his Hall of Fame career, the Splendid Splinter more than lived up to that lofty expectation.

The roughly eight-minute conversation with the legendary Red Sox outfielder is one of dozens of interviews in the Bob Wolff Film Collection. The Museum’s Archive documents the 1995 Ford C. Frick Award winner’s brushes with the baseball luminaries of the 1950s and ‘60s as they passed through Griffith Stadium. Now fully digitized from its original 16mm film, this treasure trove gives fans the opportunity to explore seldom-seen footage in weekly installments on the Hall of Fame’s YouTube channel.

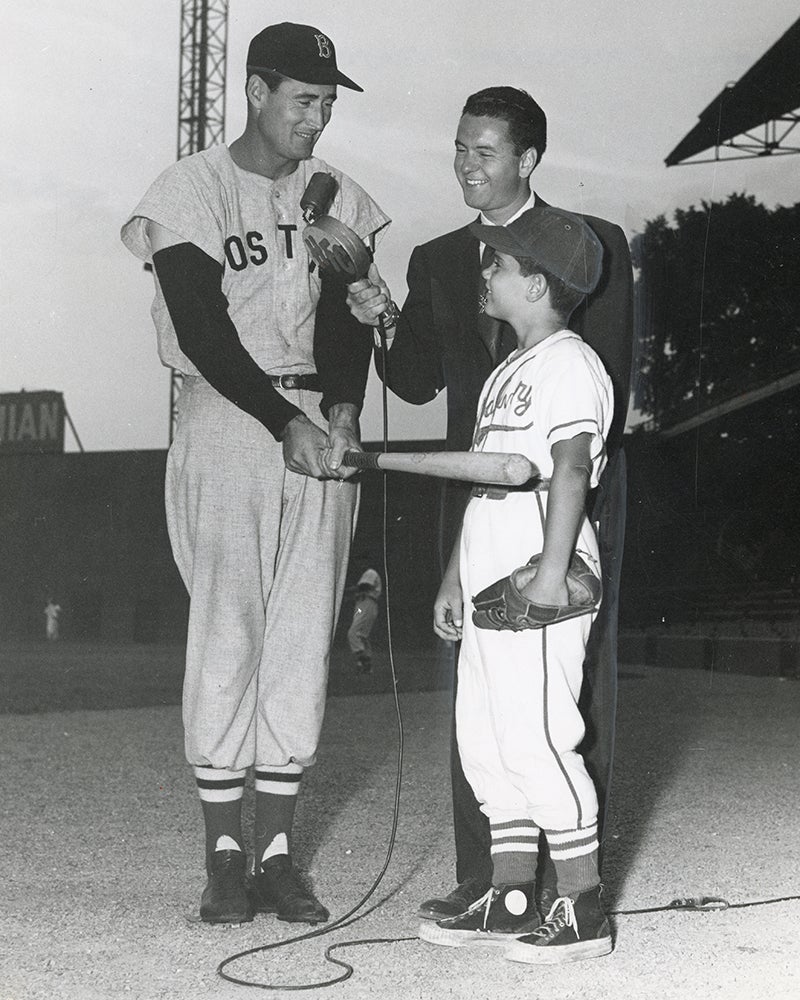

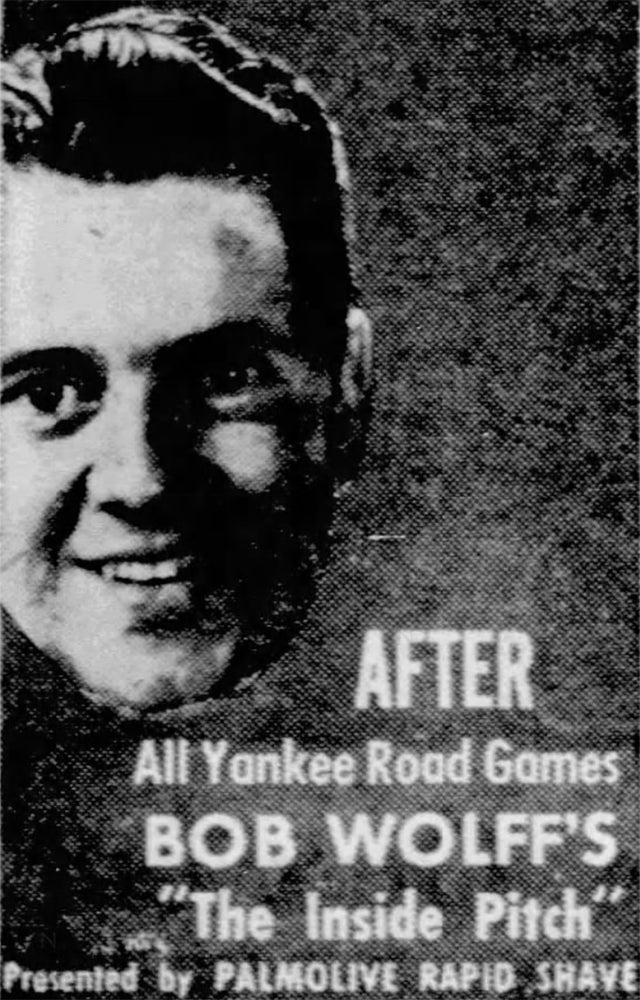

Two circumstances make this clip unique: First, it was one of two interviews – opposite Mickey Mantle – that Wolff packaged as a pilot film and pitched to WPIX, then the Yankees’ flagship television partner. It was picked up as “The Inside Pitch,” a series that ran after Yankees road games in 1958 and later expanded to the Boston, Kansas City and Washington markets.

The second unique element is that Wolff secured this interview during a period of Williams’ career when he often shunned reporters. Two war-shortened campaigns, recovery from a broken collarbone and a short-lived retirement between the 1954-55 seasons raised the specter of when he would hang up his spikes. Then in August 1956, Williams was fined $5,000 after spitting toward jeering fans at Fenway Park.

Despite the slugger’s reputation as being prickly with the press, Wolff developed a rare rapport with Williams. The ever-cordial play-by-play man considered him a friend and put the mercurial hitter at ease with a smooth, subtle line of questioning. So after an uncharacteristic rebuff before a game in Washington, Wolff sought out Williams to clear the air.

They struck a deal: If he was performing to his standard, batting around .330 with 20 home runs, Williams would honor the interview request on his next trip to Washington in 1956. Wolff raised a gentle reminder of this oath following the incident, and Williams kept his word.

“I told Ted just before going on here that I’d throw any question his way,” Wolff opens as the two stand in front of the third base dugout. “Ted said shoot ‘em and he’ll give us the answers.”

It took no time for the discussion to turn toward hitting. Williams listed Mantle, Al Kaline and Harvey Kuenn among his favorite players to watch but also commended two lighter hitting contemporaries, Baltimore shortstop Willy Miranda and Washington catcher Clint Courtney.

“There’s something about certain players that catches your eye, and you just like to watch them,” Williams said. “Certainly you like to see guys with power, and the better hitters, you always watch them. You always see what they’re doing that’s keeping them where they are and making them a little better than anyone else.”

Williams, a few days removed from his 38th birthday, was still sporting the graceful left-handed swing that turned heads when he starred in the Pacific Coast League as a teenager.

“It was two things that happened that were very instrumental towards me not changing my way of hitting,” Williams said. “One was that I used to go out and talk to (San Francisco Seals manager) Lefty O’Doul all the time. And he used to always tell me, ‘No matter whatever happens to you in baseball, don’t ever let anybody change your swing.’ I took that to heart, and I never have. I never tried to copy anything.

“And the other thing was that I signed with a club that had a lot of old pitchers. I would hit, say, a fastball the first time I got up, and then they’d start getting me out on dinky curves, like they can get young hitters out with pretty easily because they’re more ready for fastballs than anything else. I’d start talking to these older pitchers and they start putting bugs in my ear and saying, now just lay for that pitch next time, and I’d get up there and sure enough, here it comes and I’d hit it.”

Because the Wolff Collection films are preserved on YouTube in their on-air entirety, viewers are reminded that the unpredictability of live television is nothing new. Wolff was starting to steer the conversation toward the recent incident that provoked the fine when an unidentified man interrupted the broadcast with a request that Wolff provide an autograph. Wolff kept his composure as he directed the interloper out of frame.

“I didn’t want to reveal my being upset on camera, believing that this important interview was being spoiled,” Wolff wrote in the afterword to the 2013 book “Facing Ted Williams.” “So I smiled, explained I’d take care of the autograph a bit later, and continued speaking to Ted. The fan started to leave, and then returned to ask, ‘Is that Ted Williams with you?’ Again a big smile, a ‘yes,’ and again, ‘please come back a bit later.’ This time the fan left.

“I was afraid to look at the filmed result, so I stayed outside the viewing room, disheartened that this sought-after prized interview might no longer be good enough to use.

“As the TV staff viewed it, I kept waiting for their verdict. Through the wall, however, I heard chuckles of mirth and then unrestrained uproarious laughter as they viewed my forced smile next to Williams’ facial agony. The close-up of Ted showed him scowling, then enraged, and then his lips muttering a few swear words illustrating his wrath. This was visual proof of Ted’s emotion, which was what the interview was about.”

Returning to Williams, Wolff asked whether players had any obligation to the fans and the extent to which the relationship was a two-way street.

“I certainly think that all ballplayers have the same feeling; that without the fan, of course, there wouldn’t be this game of baseball as we know it,” Williams said. “With the same token, you can take a ballplayer’s view of it too… it’s a pretty even proposition on that, as far as what one owes the other.

“I’m sure that well over 90 percent of (the fans) are for me, and I think that’s a pretty good average.”

The conversation ends on a heartfelt note. Williams, not one for sentimentality, closes by thanking Wolff for his impartial coverage and professional relationship.

“I’ve known you for quite a little while, and I would like to thank you for being so nice and fair with me,” Williams said. “That’s the reason I go on the program with you, because I feel like you’re a pretty fair guy, and so if I’m any help to you at all, I’m happy.”

“Well, thank you, Ted,” Wolff responded. “I guess you know that I like you genuinely as a person, quite aside from your ballplaying, and I’m looking forward to many other years together and continued good luck to you.”

In spite of the rumors, Williams’ career was far from complete. He captured his fifth and sixth batting titles, hitting .388 in 1957 and .328 in 1958, before retiring in 1960. Wolff moved with the Senators to Minnesota in 1961, calling the first season of Twins baseball before assuming lead play-by-play responsibilities for NBC’s Game of the Week in 1962.

Decades later, Wolff – who passed away in 2017 – continues to pull back the curtain and bring a new audience closer to the mystique of baseball’s golden age.

Kourage Kundahl is the director of digital content at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum