- Home

- Our Stories

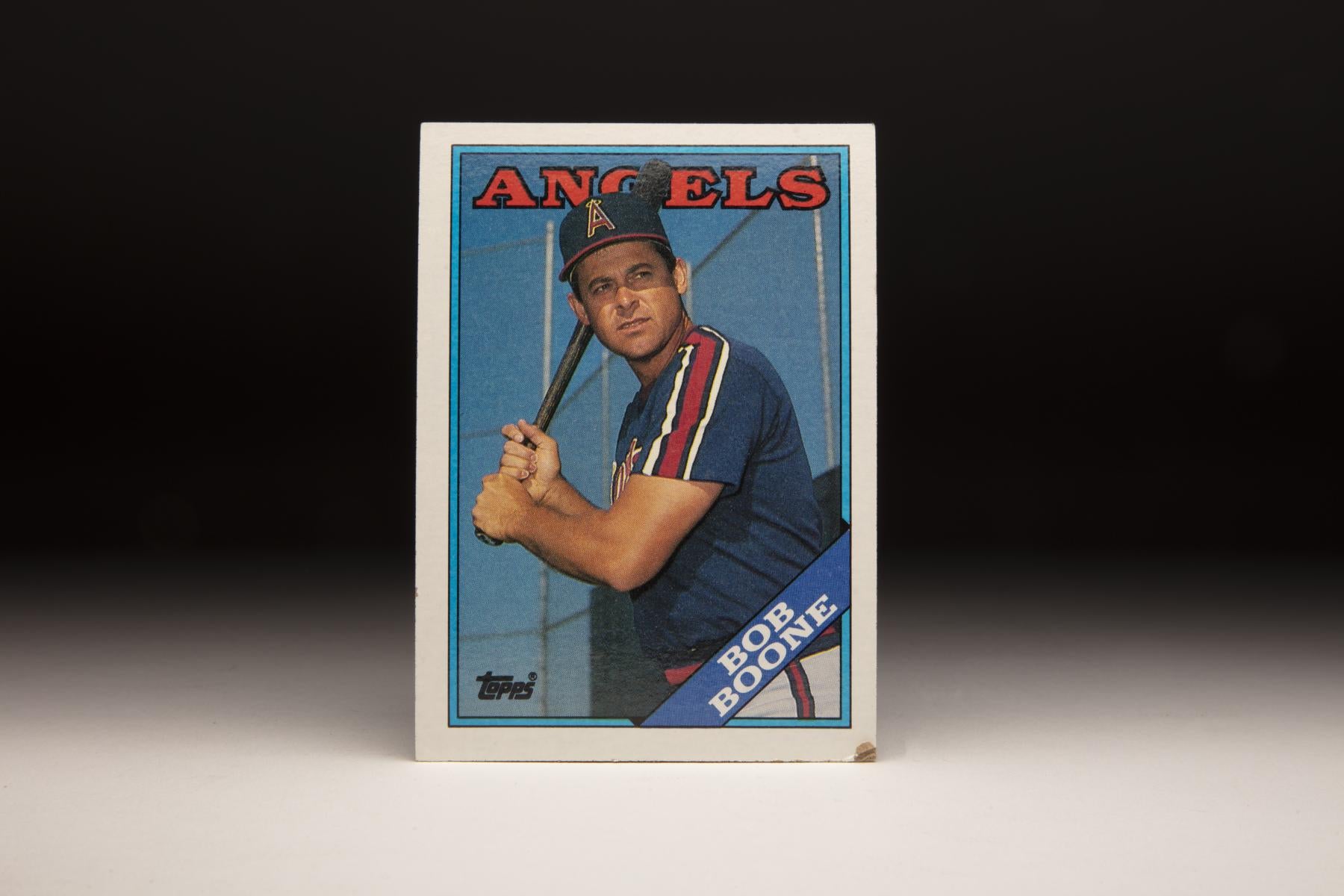

- #CardCorner: 1988 Topps Bob Boone

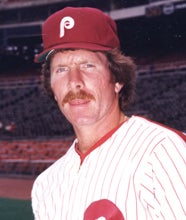

#CardCorner: 1988 Topps Bob Boone

He caught more than 2,200 big league games, managed another 815 and is part of a select few families that had three generations of major leaguers.

In short, it would be hard to find someone who has experienced more baseball than Bob Boone.

Born Nov. 19, 1947 in San Diego, Bob Boone was the son of Ray Boone, who debuted in the big leagues in 1948 with Cleveland and played 13 MLB seasons. A direct descendant of frontier legend Daniel Boone, Ray Boone grew up in San Diego after his father, who was raised in Kansas on a farm, moved to the West Coast while in the Navy.

Phillies Gear

Represent the all-time greats and know your purchase plays a part in preserving baseball history.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

The year-round warm weather in California helped Bob follow Ray’s footsteps to the big leagues.

“From day one with Bob, that’s all it was with him – baseball,” Ray told the Kansas City Star in 1997. “You didn’t even have to say ‘Let’s play catch’ with him because he was always there.”

Traded from Cleveland to Detroit in 1953, Ray Boone found his hitting stroke with the Tigers and led the American League with 116 RBI in 1955. Bob would follow his father to the park once he was old enough, and when Ray joined the Kansas City Athletics in 1959 it led to an injury for Bob.

“I remember one time when Bob was shagging balls in Kansas City, and I heard a roar go up…and I knew Bob made a catch,” Ray Boone said. “The fans liked to see a little kid make a play out there. The next thing I knew he was standing behind me, and I looked around and said: ‘What’s the matter?’ He said: ‘I hurt my thumb.’ So I sent him in to see the trainer. About an hour later, he came back with his thumb in a cast. He’d broken it.”

Ray Boone’s big league career ended the following season. Bob, meanwhile, was determined to follow in Ray’s footsteps and enrolled at Stanford University after his high school graduation. Then a third baseman, Boone was an All Pacific-8 selection in 1968 and even pitched some games, striking out 12 in Stanford’s league opener in 1969 against UCLA.

Following the 1969 season – when Boone hit .311 with seven home runs in 46 games while going 9-1 with a 1.27 ERA in 85 innings – the Philadelphia Phillies selected him in the sixth round of the June MLB Draft. He exited Stanford with a degree in psychology and all the credits necessary to begin medical school – a goal which he pursued for a time but later abandoned in favor of baseball.

“With his size and the way he can swing a bat, we think he has to be in the big leagues in a couple of years,” Phillies scout Eddie Bockman told the Oakland Tribune of Boone, who had grown into his 6-foot-2, 195-pound frame by that point. “We figure on him as a third baseman. He has in what baseball terminology is a “plus” arm, and he has unusually fine agility for such a big man.”

Sent to Raleigh-Durham of the Class A Carolina League, Boone hit .300 with five homers and 46 RBI in 80 games – 79 of which were spent at third base. The Phillies brought Boone to the Florida Winter Instructional League after the season, then invited him to their Spring Training camp in 1970.

Now firmly established as a top prospect, Boone played in only 20 games for Double-A Reading in 1970 due to Army commitments. Then in the fall of 1970, Boone returned to the FWIL, where the Phillies – who had highly regarded Don Money already at third base and would draft Mike Schmidt in the second round in 1971 – converted Boone into a catcher.

“I’m enjoying catching; I feel comfortable,” Boone told the Lancaster (Pa.) Sunday News. “Still, I’m not certain I’m a catcher. I think of myself as a two-position player.”

But the Phillies were certain that Boone’s future was behind the plate.

“Boone looks simply great – there is no other word,” Phillies coach Andy Seminick, the starting catcher on the Phillies’ 1950 National League championship club, told the Sunday News. “Everything seems to come natural to Bob. He’s got soft hands, one of the strongest arms in our organization (and) reacts quickly to balls in the dirt.

“Give him 300 games under his belt – two seasons in the minors – and he’ll be ready for the Phillies. And put this down too: He’ll be a .270 hitter.”

Boone played 92 games back at Reading in 1971 – 33 as a catcher. Then in 1972, Boone was promoted to Triple-A Eugene of the Pacific Coast League, where he caught 133 games and hit .308 with 32 doubles, 17 homers and 67 RBI. With Seminick as his manager, Boone aced a crash course in becoming a catcher.

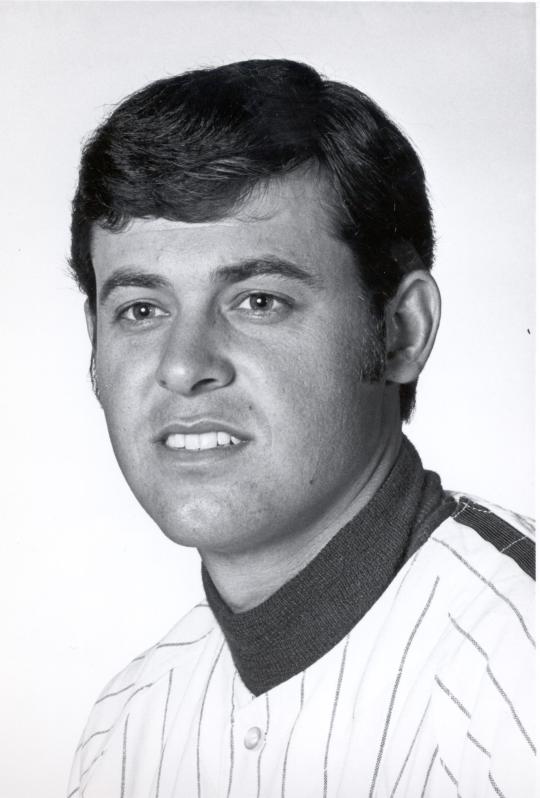

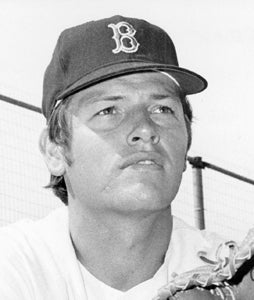

Boone made his big league debut as a September callup on Sept. 10 and played in 16 games for the Phillies down the stretch. Then, in 1973, Boone made the Phillies Opening Day roster despite a rough spring that saw manager Danny Ozark openly question his pitch selections. But Ozark stuck with Boone and quickly moved him into the starting lineup.

By summer, Boone’s play behind the plate was the talk of the National League.

“He’s twice the catcher he was at the start of the season,” Padres manager Don Zimmer told the Camden (N.J.) Courier-Post. “He swings the bat like he means it and he seems to know how to handle pitchers.”

Ozark, meanwhile, had a catcher that would one day take the Phillies to the World Series.

“He is the manager of this ballclub on the field,” Ozark told the Courier-Post. “He runs the team.”

Boone finished his rookie season with a .261 batting average, 10 home runs and 61 RBI in 145 games. Defensively, Boone led all NL catchers with 89 assists while throwing out 47.4 percent of would-be base stealers. Finishing third in the NL Rookie of the Year balloting, Boone drew comparisons defensively to the gold standard of catchers: Johnny Bench.

In 1974, Boone suffered from a bit of a sophomore slump brought on by a back injury suffered in Spring Training, hitting .242 with three homers and 52 RBI while leading the NL in stolen bases allowed (99) and errors among catchers (22). Phillies ace Steve Carlton went public with the fact that he preferred to work with other catchers.

In 1975, Boone lost playing time when Johnny Oates was acquired from the Braves along with Dick Allen on May 7, and Oates batted .286 over 90 games with the Phillies while Boone hit .246 in 97 contests.

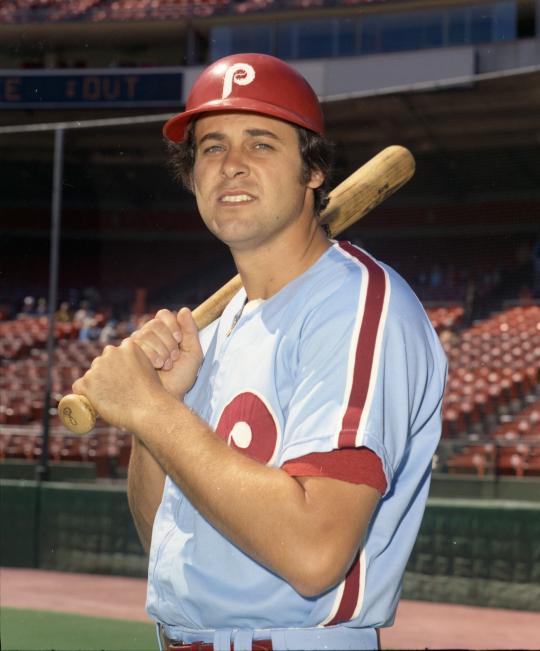

But with his career seemingly at a crossroads in 1976, Boone earned his first All-Star Game selection – no small achievement in a league that featured Ted Simmons, Manny Sanguillén and Bench among others – while hitting .271 and finishing third among NL catchers with a .990 fielding percentage. Boone credited work with coach Billy DeMars on his newfound success at the plate, and he took advantage of playing time created when Oates was injured in a home plate collision on Opening Day.

Boone’s play behind the plate helped Philadelphia win 101 games and advance to the National League Championship Series, where Boone went 2-for-7 in his first postseason action as the Reds swept the Phillies in three games.

The next season, the Phillies again won 101 games and again captured the NL East title as Boone – who agreed to a three-year deal worth $460,000 that carried him through the 1979 season – had his best all-around season to date, hitting .284 with 11 homers and 66 RBI. He appeared in all four games of the NLCS vs. the Dodgers, hitting .400, but started just two of the contests as Tim McCarver got the nod when Carlton took the mound. Once again, the Phillies failed to reach the World Series.

In 1978 – at the age of 30, a point where many catchers begin slowing down – Boone won the first of what would be seven Gold Glove Awards, snapping Bench’s string of 10 straight years winning the award. Hitting .283 with 12 homers and 62 RBI, Boone earned a second All-Star Game selection and finished 23rd in the NL MVP race after again helping Philadelphia win the NL East. But again, the Phillies lost to the Dodgers.

Boone, however, never seemed to tire of the work necessary to produce success on the field. As he aged, he committed to a workout regime consisting of calisthenics and stretching that allowed him to exhibit uncommon durability.

“I was born and raised around (hard work),” Boone told the Philadelphia Inquirer in 1979. “I don’t know if you’d call it hereditary or what, but I always worked hard at what I was doing. I know what I need, I know what I have to do, and it involves a lot of hard work.”

The Phillies signed Pete Rose to a lucrative free agent deal prior to the 1979 season, hoping Rose would be the missing piece that would bring Philadelphia its first World Series title. But the Phillies never jelled in 1979 despite another stellar season from Boone where he hit .286, won another Gold Glove Award and started the All-Star Game for the first time.

Boone’s season ended on Sept. 13, 1979, when he injured his left knee in a collision with the Mets’ Joel Youngblood. But he quickly signed a new deal with the Phillies after the season that would take him through the 1983 campaign.

With their streak of three straight NL East titles snapped, the aging Phillies entered the 1980 season under new manager Dallas Green, who replace Ozark during the 1979 campaign. Boone’s batting average dropped to .229 but he still drove in 55 runs in 141 games while holding together a pitching staff that featured veterans Tug McGraw, Ron Reed, Dick Ruthven and Carlton as well as youngsters like Bob Walk and Marty Bystrom.

In a hard-fought NLCS vs. the Astros, Boone’s two-run single against Nolan Ryan in the second inning of Game 5 gave Philadelphia a 2-1 lead. Then in the eighth inning with Larry Bowa on first base, no one out and the Phillies trailing 5-2 against Ryan, Boone hit a one-hopper back to the mound. Ryan tried to backhand the ball but it caromed off the leather and went for an infield hit – setting up a five-run rally in a game Philadelphia ultimately won 8-7 in 10 innings to advance to the World Series.

Had Ryan been able to field the ball cleanly, it would have likely resulted in a rally-killing double play.

Spurred on by his good fortune, Boone hit .412 in the World Series against the Royals with two doubles, four RBI and four walks, helping Philadelphia win its first Fall Classic title.

“We don’t do anything easy, do we?” Boone told Green after the Phillies won Game 6 by a score of 4-1 to clinch the title.

The Phillies returned to the postseason in 1981 but were eliminated by the Expos in the NLDS. Boone hit just .211 in 76 games that year – and the Phillies’ management, possibly believing that the 34-year-old Boone was in his final stretch as a productive player – sold the contract of their longtime catcher to the Angels on Dec. 6, 1981, in exchange for a reported $250,000.

“Boone is not a .211 hitter,” Angels manager Gene Mauch told the Associated Press after the deal became official. “Anyway, that doesn’t concern me. I just want him to catch and throw and direct the pitching staff.”

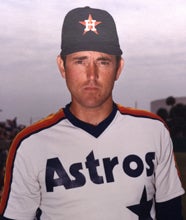

For the next seven seasons with the Angels, Boone did just that. In an amazing display of durability, Boone averaged better than 142 games behind the plate from 1982-86 during his age-34 through age-38 seasons. During that time, he won two more Gold Glove Awards (becoming the first catcher to win Gold Glove Awards in each league), earned a selection to the 1983 All-Star Game and led the Angels to American League West titles in 1982 and 1986.

After hitting .256 in both 1982 and 1983, Boone’s mark dropped to .202 in 1984. But he still managed to put the ball in play as regularly as ever. And though he hit just .222 in 1986, he batted .455 with 10 hits in the seven-game ALCS vs. the Red Sox that year. In Game 5 – a contest the Angels seemed to have won before an epic Red Sox rally – Boone tied Norm Cash by becoming just the second player of at least 38 years of age to hit a home run in an ALCS game.

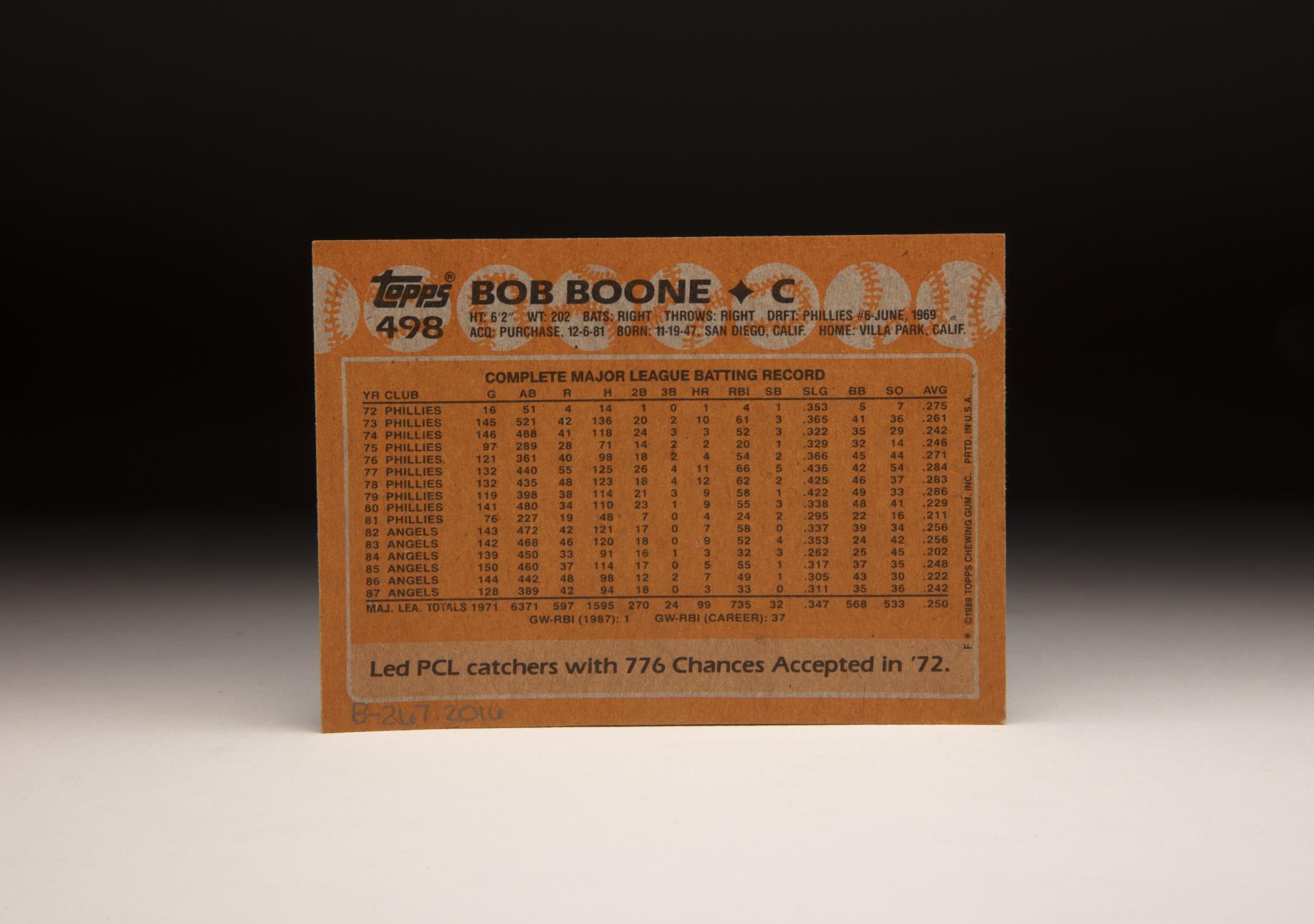

Boone’s defense during these years – and beyond – remained exemplary. He led AL catchers in assists five times from 1982-88 and led the league in caught stealing percentage three times during the same period. He won three straight Gold Glove Awards from 1986-88 and even hit a career-best .295 in 1988. But when he was made a new-look free agent following that season, the Angels let Boone go in favor of Lance Parrish. Boone quickly signed a one-year deal with the Royals.

“I think there’s still a lot of play left in Bob Boone,” Boone said of himself to Knight News Service.

Boone proved correct, winning his seventh Gold Glove Award – he remains the oldest catcher ever to win the award – in 1989 while hitting .274. But in 1990, a finger injury and the emergence of young Mike Macfarlane limited Boone to just 40 games. Now the all-time leader in games caught with 2,225, Boone went to camp with the Mariners in 1991 as a non-roster player but did not make the Opening Day roster.

Boone would not play in the big leagues again but quickly got on with his second career when he was named the manager of the Athletics’ Triple-A team in Tacoma for the 1992 season. After two seasons, Boone served as the Reds bench coach in 1994 – the same year his son, Bret, played the first of five seasons for Cincinnati and also the year the Reds drafted another of Boone’s sons, Aaron, in the third round out of the University of Southern California.

“He’s got a good head on his shoulders,” Bret told the Cincinnati Post about Aaron. “And, mentally, he’s very strong – just like my dad.”

Bret Boone would play 14 big league seasons, enabling the Boones to become the first three-generation big league family. Aaron Boone would play 12 seasons in the majors before embarking on a successful managerial career.

Bob Boone took over as the Royals manager in 1995 and skippered the team into the 1997 season. He then managed the Reds in 2001, 2002 and 2003.

Carlton Fisk and Iván Rodríguez eventually passed Boone on the all-time games caught list, but Boone still ranks third and will likely stay there for at least another decade if not longer. Over 19 seasons in the majors, Boone hit .254 with 1,838 hits, 303 doubles and more walks (663) than strikeouts (608).

His greatest legacy, however, may be his family name.

“My pride or feelings about my family didn’t change because Bret got to the major leagues to make us the first three-generation family,” Boone told the Kansas City Star. “The big part for my dad or me is our time is over – and you want to see your kids succeed.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum