- Home

- Our Stories

- Advent of regional rail service made baseball possible

Advent of regional rail service made baseball possible

In 1969, during a year-long celebration of the 100th anniversary of professional baseball, the Massachusetts-based Fleetwood Recording Co. produced an album that sought to tell the history of the game in two action-packed, anecdote-laden sides of vinyl.

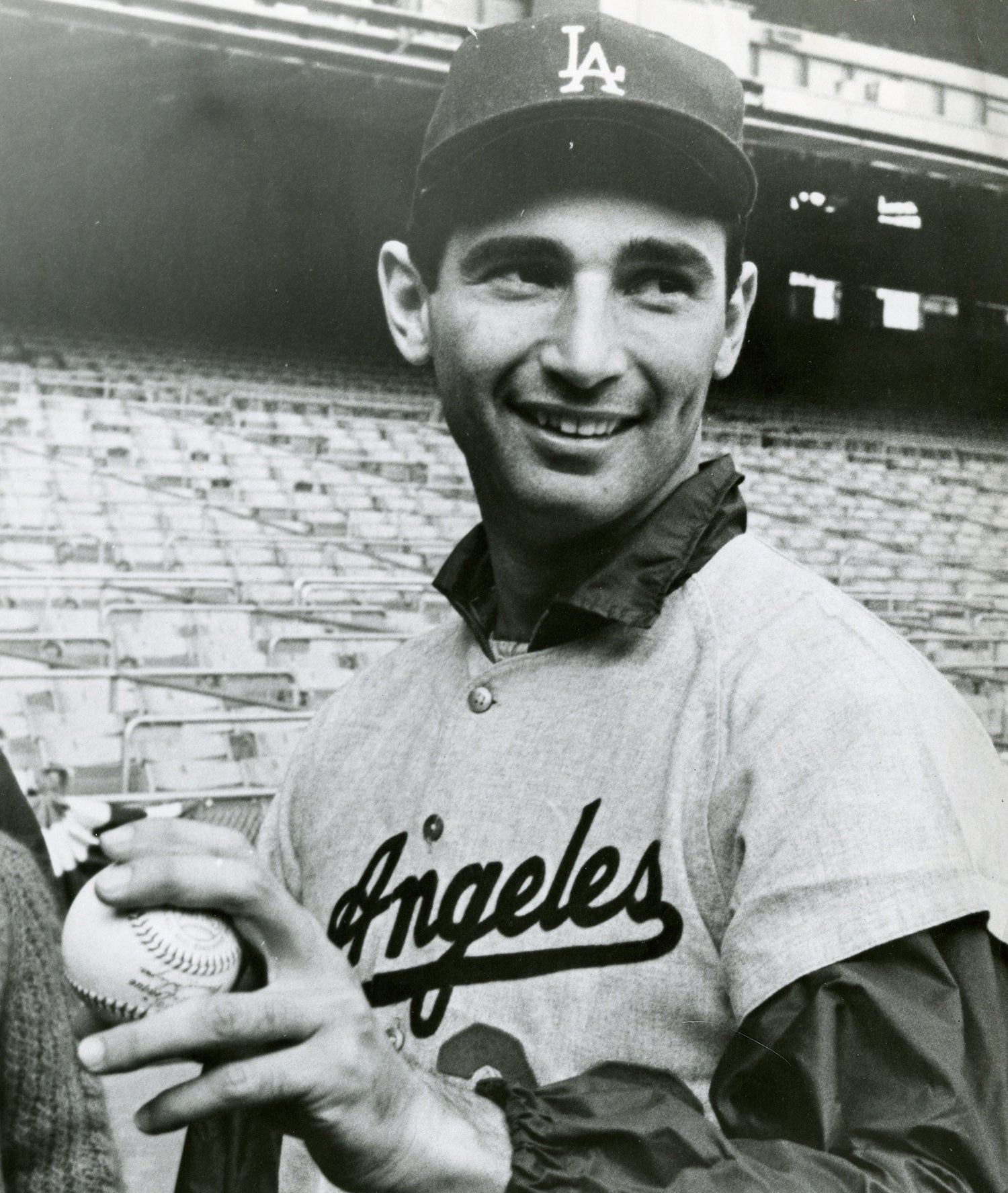

Produced in concert with Major League Baseball and narrated by actor James Stewart and broadcaster Curt Gowdy, the album had everything ball fans would have expected, from Russ Hodges’ heart-pounding call of Bobby Thomson’s Shot Heard Round the World to Vin Scully’s rhythmic, exquisitely paced description of Sandy Koufax striking out Harvey Kuenn to compete the Dodger legend’s perfect game.

It also had some surprises, including a scratchy recording of an aging ballplayer from the 19th century reminiscing about the days when teams depended on America’s railways to get from city to city.

“I was playing in Des Moines, Iowa, and you’d get on a train and you’d carry your bats and your own bag and your own uniform rolled up . . . you’d get on a train with the old wicker seats and they were burning coal, and you’d get in the car in July and August and go from Des Moines to Wichita, Kansas, all night, part of the next day, and if you’d open up the window you’d be eatin’ soot and cinders all night, and if you closed the window you’d roast to death.”

Baseball. Trains.

Without one, we never would have had the other.

“They kind of came along at the same time, and it was huge,” said author and historian Peter Morris, who has written extensively on 19th century baseball. “Any time something is new and popular, anything that’s a trend is going to hitch itself to that — metaphorically and in this case literally.”

And baseball in the mid-19th century was clearly trending upward.

“But the whole idea of trying to get nine people from one place to another was not at all easy, at a time when the roads were still pretty primitive and most of the transportation was by water,” Morris said. “Just getting over the Allegheny Mountains in the 19th century was an arduous task.”

In 1848, when the California Gold Rush began, many fortune seekers from the east would travel by boat around Cape Horn in South America and then head north to San Francisco. The first Transcontinental Railroad, which opened in 1869, changed that. As Stephen Ambrose wrote in “Nothing Like It in the World,” his wonderful biography of the Transcontinental Railroad, “ . . . less than a week after the pounding of the Golden Spike, a man or woman could go from New York to San Francisco in seven days . . . so fast, they used to say, ‘that you don’t even have time to take a bath.’”

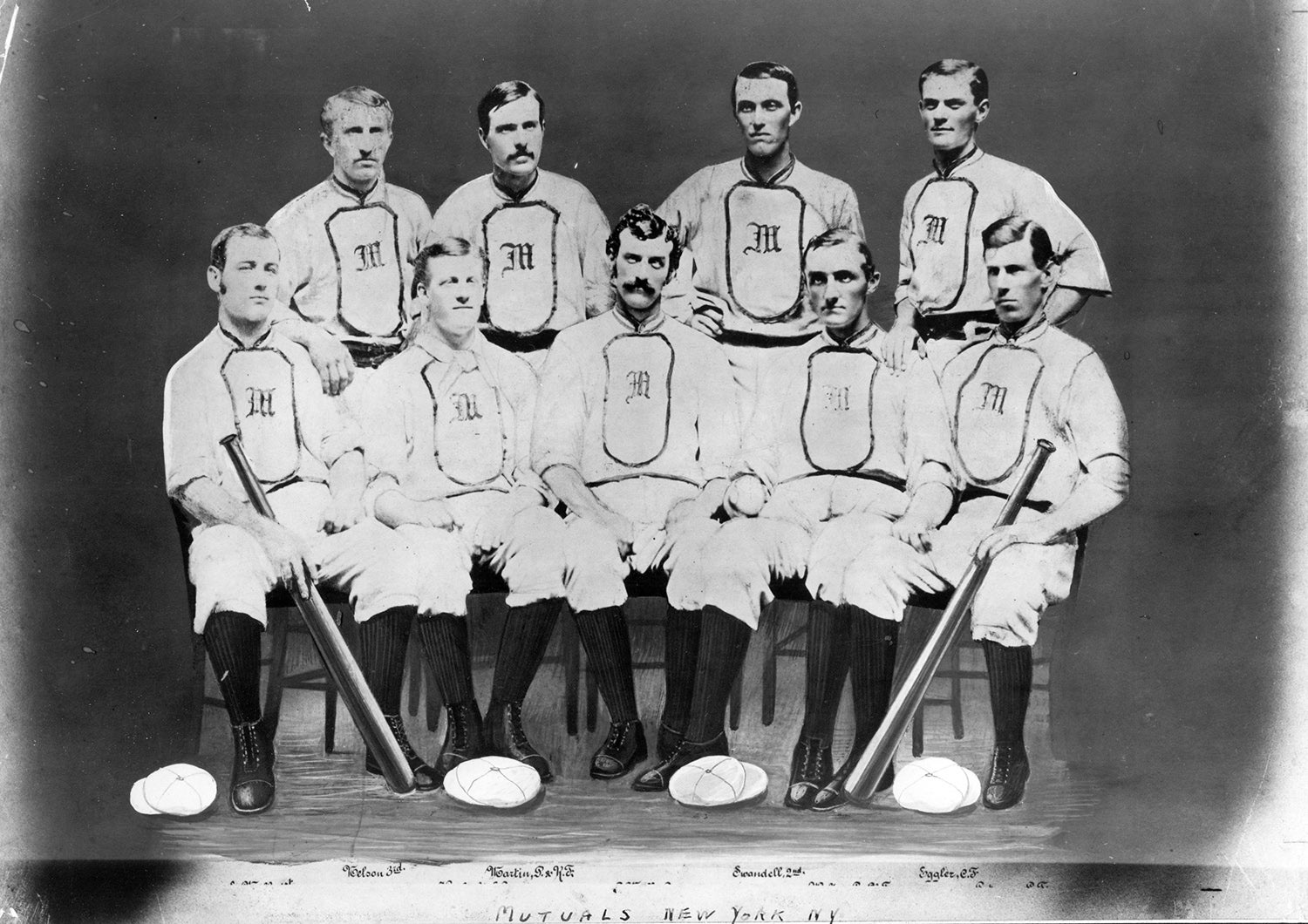

That very year — 1869 — was when Harry Wright founded one of the first openly professional baseball teams, the Cincinnati Red Stockings. And just like that, teams from one city were traveling to play teams in another city, teams that had different uniforms, different nicknames, and, especially, before the evolution of baseball, different rules.

“You really don’t have standard rules until you get teams from one city playing teams in the next city,” Morris said. “You had players in Cleveland playing by one set of rules, and you had players in Cincinnati playing by a different set of rules. But you see the rules start to become standard in the late 1860s as the railroad is connecting the country and you see the professional game of baseball coming. It’s really not a coincidence.”

Baseball would never have advanced to the degree of blossoming as America’s “National Pastime” had not the railroads become advanced to the degree that passengers could travel from one city to another in hotel-level comfort. Those wicker chairs and coal furnaces would over time be replaced by plush seating and steam engines; by the 20th century players were bedding down in sleeper cars and taking their meals in dining cars.

It was not always luxurious — certainly not by today’s standards. As the late Boston Red Sox outfielder Dom DiMaggio wrote in “Real Grass, Real Heroes”:

“The rookies traveled in the third car, the last one — the one that whipped from side to side every time the train went around a bend.”

But, wrote DiMaggio, “Ballplayers from the 1940s will tell you to a man that when baseball teams started flying, a certain bonding that held teams together went out of major league baseball. We got to know each other as only you can when you’re on a train together for 24 hours, or 36 or more.”

Red Sox traveling secretary Jack McCormack said he was given the same information by the late Johnny Pesky, who played with DiMaggio on the Red Sox in the 1940s and ‘50s.

“He told me the players got very close,” McCormack said. “A lot of card games, lot of time to talk to each other.”

This may be true, but just as the train was vital for the evolution of baseball’s transformation from various town teams to a national phenomenon, air travel made possible the 1957 moves of the Brooklyn Dodgers and New York Giants to Los Angeles and San Francisco, thus opening up the west coast for Major League Baseball.

But this isn’t to say that the train, in all its glory, has been dismissed by big league ball clubs as a mode of transportation. To this very day some east-coast teams still rely on trains from time to time, and for the same reasons the Cincinnati Red Stockings were using them in 1869 — because they’re the easiest way to get from Point A to Point B.

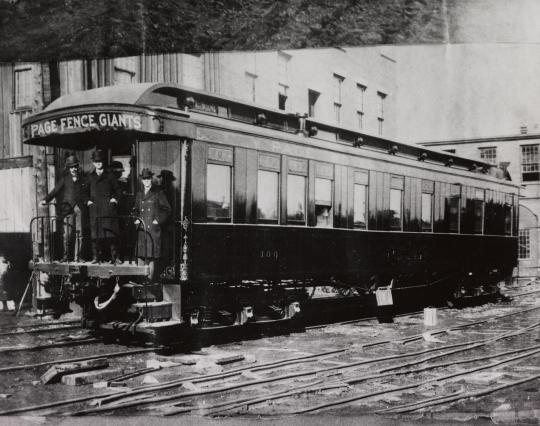

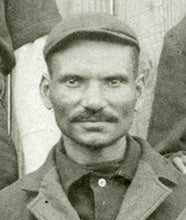

The Page Fence Giants, a top pre-Negro Leagues team of the 19th century that featured future Hall of Famer Sol White, traveled by train in a car that advertised the team. The advent of cross-country train travel in the mid-19th century allowed baseball to expand from a local to a national game. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

McCormack, as part of his job, has become a student of how teams traveled in the days before airports came into everyday use.

“That’s why Monday off-days came to be, because teams on the east were traveling to the west – Chicago and St. Louis,” McCormack said. “So you’d have those Sunday doubleheaders before making those 12 to 15-hour trips.

“I think it would be fun,” McCormack said. “It does get a little nostalgic, to me and to some of the players as well. I was thinking about that a while back when we were at the train station and there was a guy shouting, ‘Allllllll aboarddddd!’ and then, bango, you’re off in five seconds.

“It reminded me that we were doing something from days gone by. It was a good feeling.”

Steve Buckley is a senior writer for The Athletic