- Home

- Our Stories

- Feller, Paige teamed up for 1946 barnstorming tour

Feller, Paige teamed up for 1946 barnstorming tour

A historic barnstorming tour, with teams led by two of the greatest pitchers in baseball history, took place soon after World War II and helped usher in a new era of opportunity.

It also changed the face of big league travel.

The year was 1946 and the Second World War had only ended the previous September. While the 16-team major leagues – still a year away from breaking its longstanding color barrier – had stayed afloat during the conflict, many ballplayers who served in the military were heading home hoping the layoff hadn’t affected their game. Hundreds had traded in their baseball togs for military uniforms, maybe none more renowned than Bob Feller.

Official Hall of Fame Merchandise

Hall of Fame Members receive 10% off and FREE standard shipping on all Hall of Fame online store purchases.

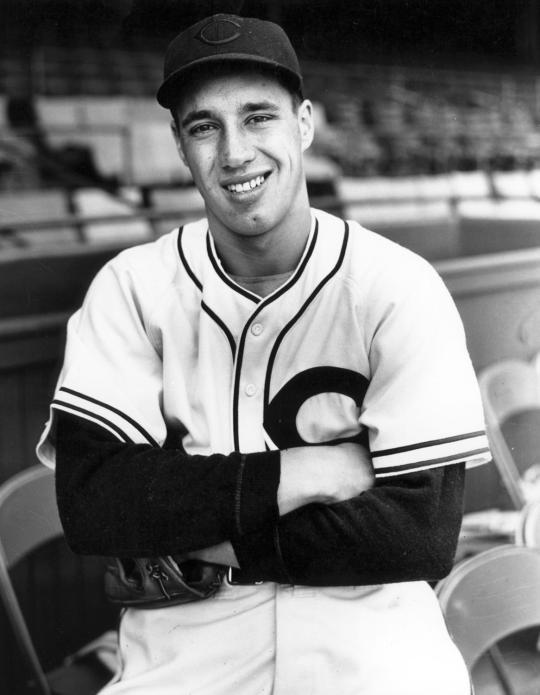

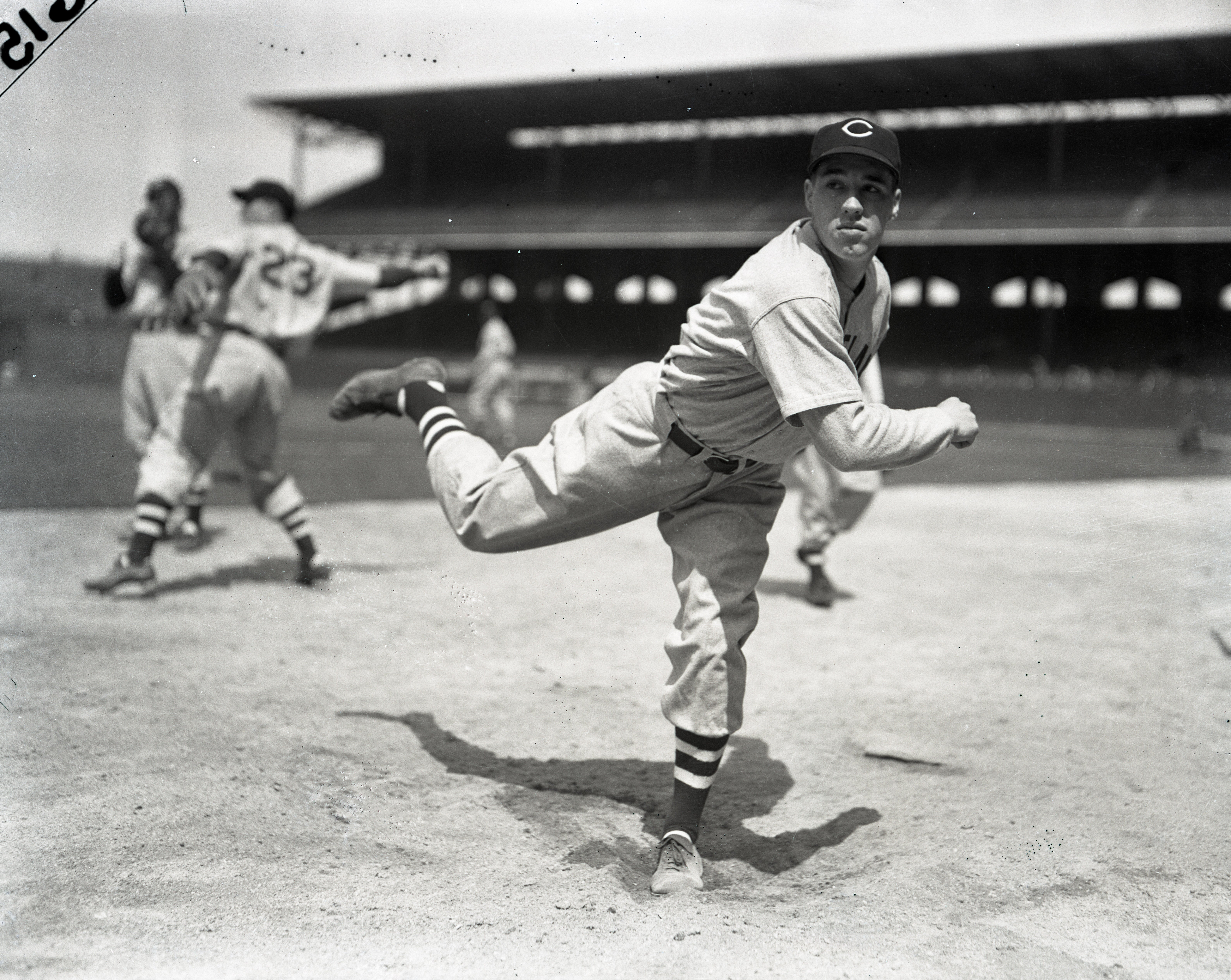

Feller burst on the baseball scene with the Cleveland Indians in 1936 before he had even finished high school. Arguably one of the hardest throwers of all time, “Rapid Robert” fanned 15 St. Louis Browns in his first major league start. Soon he was the game’s top pitcher, averaging 25 wins a season and leading the league in strikeouts from 1939-41. But the day after Japan bombed Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, the 23-year-old enlisted in the Navy missed most of the next four seasons.

It was while aboard the USS Alabama that Feller, a savvy entrepreneur his entire adult life, began to seriously consider a unique barnstorming tour pitting a team of white big leaguers against a squad made of Negro League stars as a way to augment his big league salary when he returned to the field.

“I had it all laid out,” Feller told William Marshall, author of "Baseball’s Pivotal Era, 1945-1951."

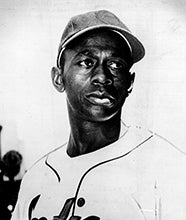

“I knew what I was going to do and I knew the people personally that I was going to have get the black clubs together – the Kansas City operator, Mr. (J.L.) Wilkinson, and Satchel Paige and many others that I wanted to oppose us.”

After making nine starts for the Indians at the end of the 1945 season upon his postwar return, Feller reclaimed his throne as one of the sport’s top hurlers in ‘46 with an America League-best 26 wins and 348 strikeouts. It was in mid-July of Feller’s stellar comeback campaign that he announced plans for a coast-to-coast exhibition tour featuring an all-star squad made up of players from both the American and National leagues and a team of the nation’s finest Negro League players.

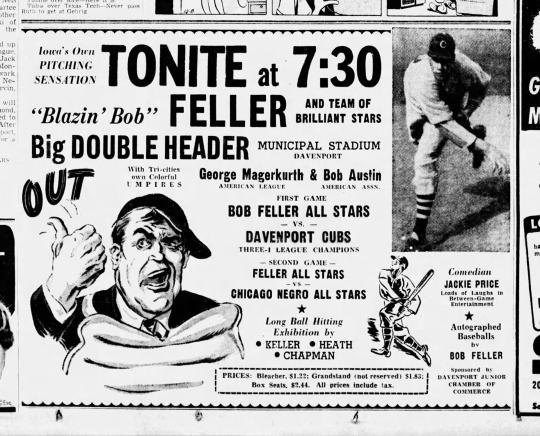

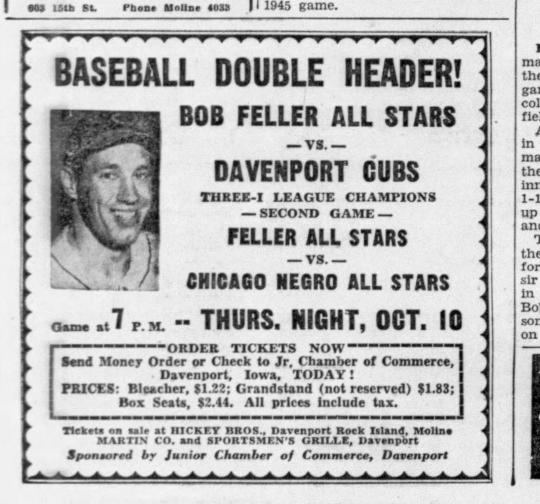

Having obtained from Commissioner A.B. “Happy” Chandler’s permission to carry the tour beyond the 10-day barnstorming limit, the 27-year-old Feller’s ambitious plans by September called for a 27-game tour beginning Sept. 30 at Pittsburgh with the itinerary including stops in such outposts as Cleveland, Chicago, Cincinnati, Baltimore, Newark, New York, Columbus, Dayton, Louisville, Davenport, Des Moines, St. Paul. Omaha, Wichita, St. Louis, Kansas city, Denver, Los Angeles, San Diego, Vancouver, San Francisco, Seattle, Portland and Tacoma. Feller even set a game in Versailles, Ky., home of Chandler.

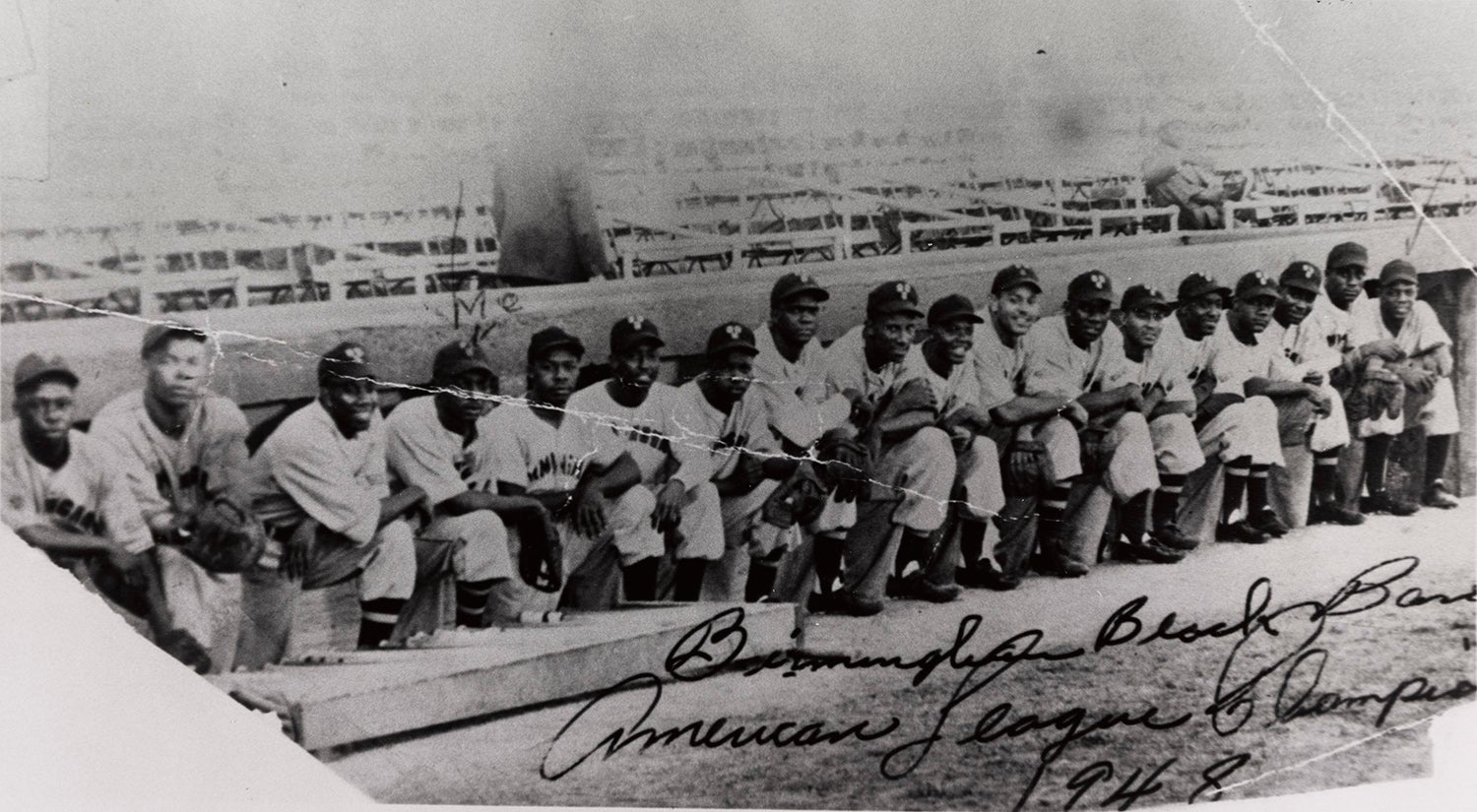

Teammates on Bob Feller’s All-Stars included Bob Lemon, Mickey Vernon, San Chapman, Charlie Keller, Spud Chandler, Phil Rizzuto and Stan Musial. Satchel Paige’s All-Stars, among the top performers from both the Negro American League and Negro American League, included Max Manning, Barney Brown, Hilton Smith, Buck O’Neil, Hank Thompson, Art Wilson, Howard Easterling and Quincy Trouppe.

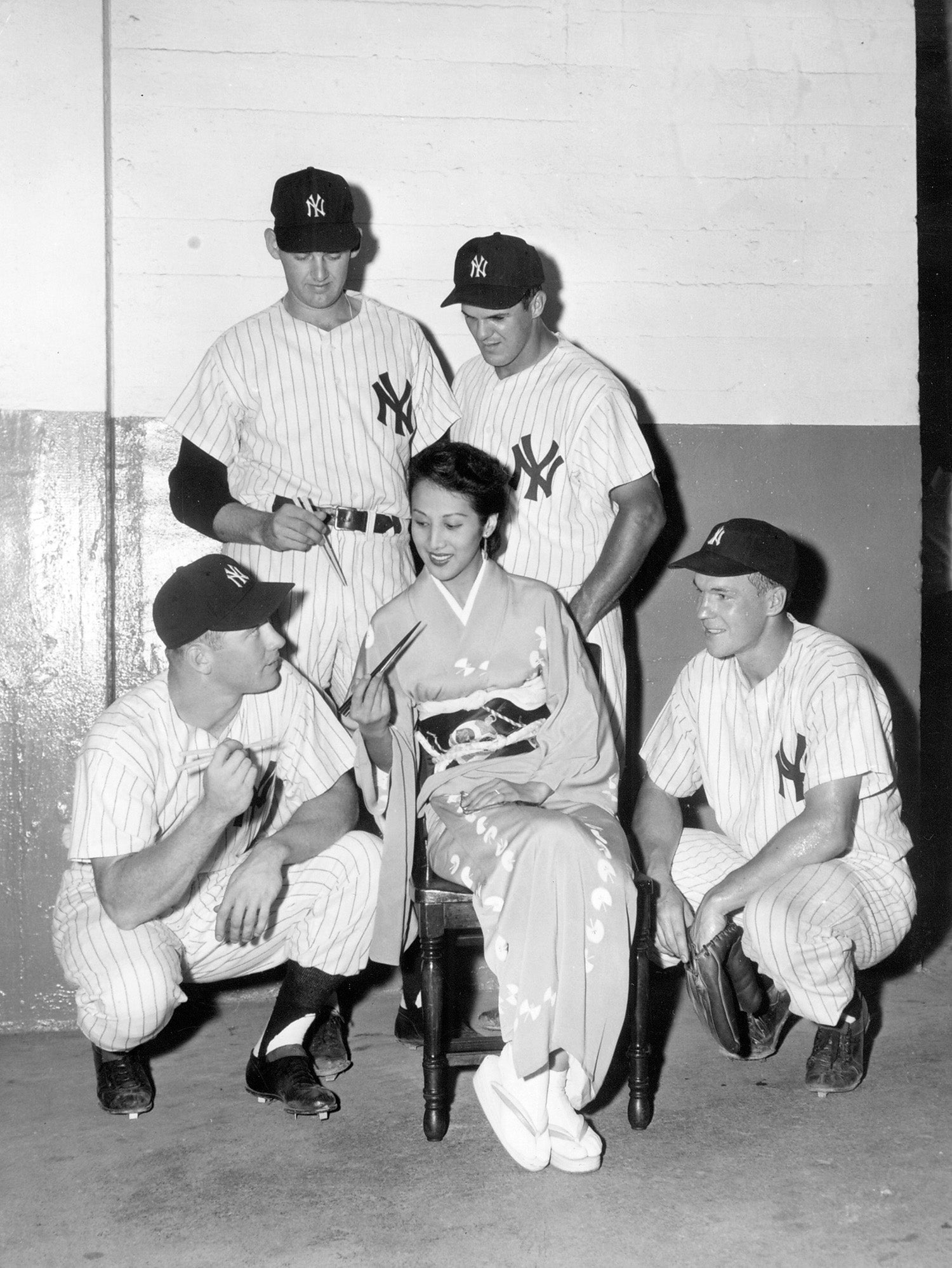

In his autobiography "Now Pitching, Bob Feller," the “Heater from Van Meter” wrote about the elaborate logistics that went into his planned transcontinental trek in 1946. No one had ever attempted to use airplanes to crisscross the country, let alone playing a game in the afternoon then flying to a second game that night hundreds of miles away.

“I had put together a full roster of players whose combined annual salaries in the majors exceeded two million dollars,” Feller wrote. “The owners of the teams didn’t like that. They said they were concerned about their players getting hurt while barnstorming. Then they really objected when they found out how were travelling. We were going to fly.

“That was unheard of for professional sports teams. They took trains. They said I was exposing their athletes to even greater dangers. But I chartered two DC-3s for a month from Flying Tigers Airlines. We had ‘Bob Feller’s All-Stars’ painted on the side and took off to play 35 games in 27 days. We were the only baseball teams travelling by air. No other barnstorming tours were doing it yet, and the major league teams hadn’t started flying either. We were pioneering the practice of a professional sports team travelling that way. Today it’s hard to imagine teams going any other way.”

Feller had a longstanding affinity for air travel, as newspapers across the country wrote about the then 22-year-old fireballer learning to fly in 1941. As was reported in The New York Times in Sept. 24, 1941, he had been taking flying instructions at Cleveland Airport for three weeks and had soloed for the first time a week prior.

“Feller is interested in flying for the sport only,” said instructor Don Patrick. “He has flown a lot of miles on airlines and had been thinking about lessons for the past two years.”

Having special access to an airplane that October came in handy for Feller.

“The only two games I missed conflicted with a contract I had made to appear at a milk convention in Atlantic City,” he wrote. “We were playing in California at that point of the tour, so I flew all night from Sacramento, made my appearance in Atlantic City, and flew all night again to rejoin our tour in California.”

While big league teams traveling by airplane increased with the West Coast expansion of the Dodgers and Giants in 1958, trains were the dominant mode of transportation for baseball players for decades. After the first major league team to fly to a game, the Reds, who went from St. Louis to Chicago on June 8, 1934, there were sporadic flights over the next decade, but it not until after World War II that plane travel became common.

There were reports in 1946 that a pair of future Hall of Famers were paid thousands of dollars by their teams to not take part in Feller’s barnstorming tour that offseason partly due to the fear of planes crashing.

“Some of the owners objected to what I was doing so much they paid their stars not to barnstorm with me,” Feller wrote in "Now Pitching, Bob Feller."

“Tom Yawkey, the owner of the Red Sox, paid Ted Williams $10,000 to stay home so he wouldn’t get hurt playing in a game or killed in a plane crash. Yawkey’s counterpart in Detroit, Spike Briggs, paid Hal Newhouser the same amount.”

According to Feller, not only did he cover all the air travel, he also carried “millions of dollars of liability insurance if either ballclub, black or white, went down.”

Buck O’Neil, in his autobiography, "I Was Right On Time," addressed not only the air travel, but also the racial component involved in the 1946 barnstorming tour.

“I was looking ahead myself during the (Negro Leagues) series, to the biggest barnstorming tour ever, when Satchel Paige and Bob Feller were going to square off against each other with their own all-star teams in games all across the country,” O’Neil wrote. “I was excited to be chosen for the Satchel Paige All-Stars, along with guys like Hilton Smith, Gene Benson and Quincy Trouppe, because I knew I’d be making more money in one month than I had made in the last six. And I was excited to able to play against guys like Mickey Vernon, Phil Rizzuto, Johnny Sain and Stan Musial right after the big-league World Series.

“But I may have been most excited about taking my first plane ride, since both teams traveled in (DC-3s), just like Satchel had been doing for some time. That’s when we found out how the other half lived.

“I also felt that, even though it was black against white, this tour was an event that could have a real effect on big-league integration, because it took place after Jackie (Robinson) had proven himself, and if a lot of us weren’t that lucky, we could at least prove ourselves against big-leaguers in these games.”

In Fay Vincent’s book, "The Only Game in Town," Feller told the former baseball commissioner: “We were interested in one thing, making money. I mean what else is there; yes we put on a good show; there was racial rivalry, not amongst the players, but amongst the fans. And we got a few laughs, they’re great friends of mine. They love me dearly. I love them dearly. I know all the guys. We made more money in that month of October than we made all year round.”

By the time the tour concluded in California at the end of October, approximately a quarter of a million fans had witnessed this unprecedented tour.

Stan Musial, who led the National League with a .365 batting average in 1946, joined Bob Feller’s All-Stars after helping the Cardinals capture the ’46 World Series. He told the Sporting News he didn’t care too much for the tour’s one-night stands.

“Good money in it, though. I sure wouldn’t do it if we couldn’t fly. It must be might rugged making jumps on a plane. At least we get some rest this way.”

The tour was described by Satch, Dizzy & Rapid Robert author Timothy M. Gay as “the most ambitious baseball undertaking since John McGraw and Charles Comiskey dreamed up their round-the-world junket in 1913.”

The Sporting News, in its tour wrap-up story on Nov. 6, 1946, called Feller the game’s greatest “money” pitcher, estimating he made $80,000 barnstorming from New York to California that year. In the 27 days the tour visited 32 cities in the United States, 17 states and British Columbia.

“Sure, I’m tired,” said Feller, “but who wouldn’t be after travelling 15,000 miles? My arm is in great shape, though, and in a few days I’m going to settle down and relax for a couple of months.

“After all, you know a fellow is only young once and I’m going to make as much money as I can while I can.”

Bill Francis is the senior research and writing specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum