- Home

- Our Stories

- Clemente’s 3,000th hit nearly made history twice

Clemente’s 3,000th hit nearly made history twice

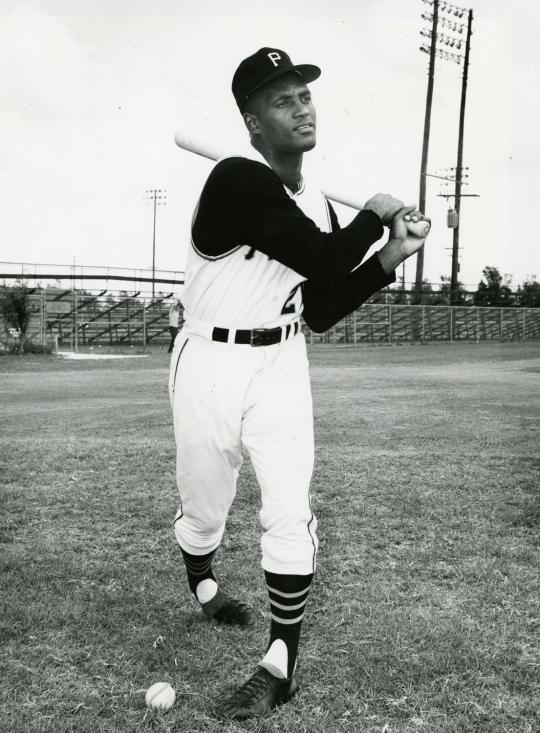

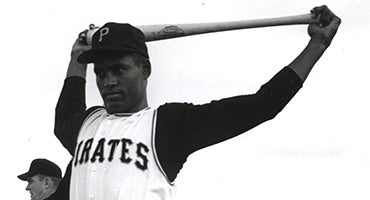

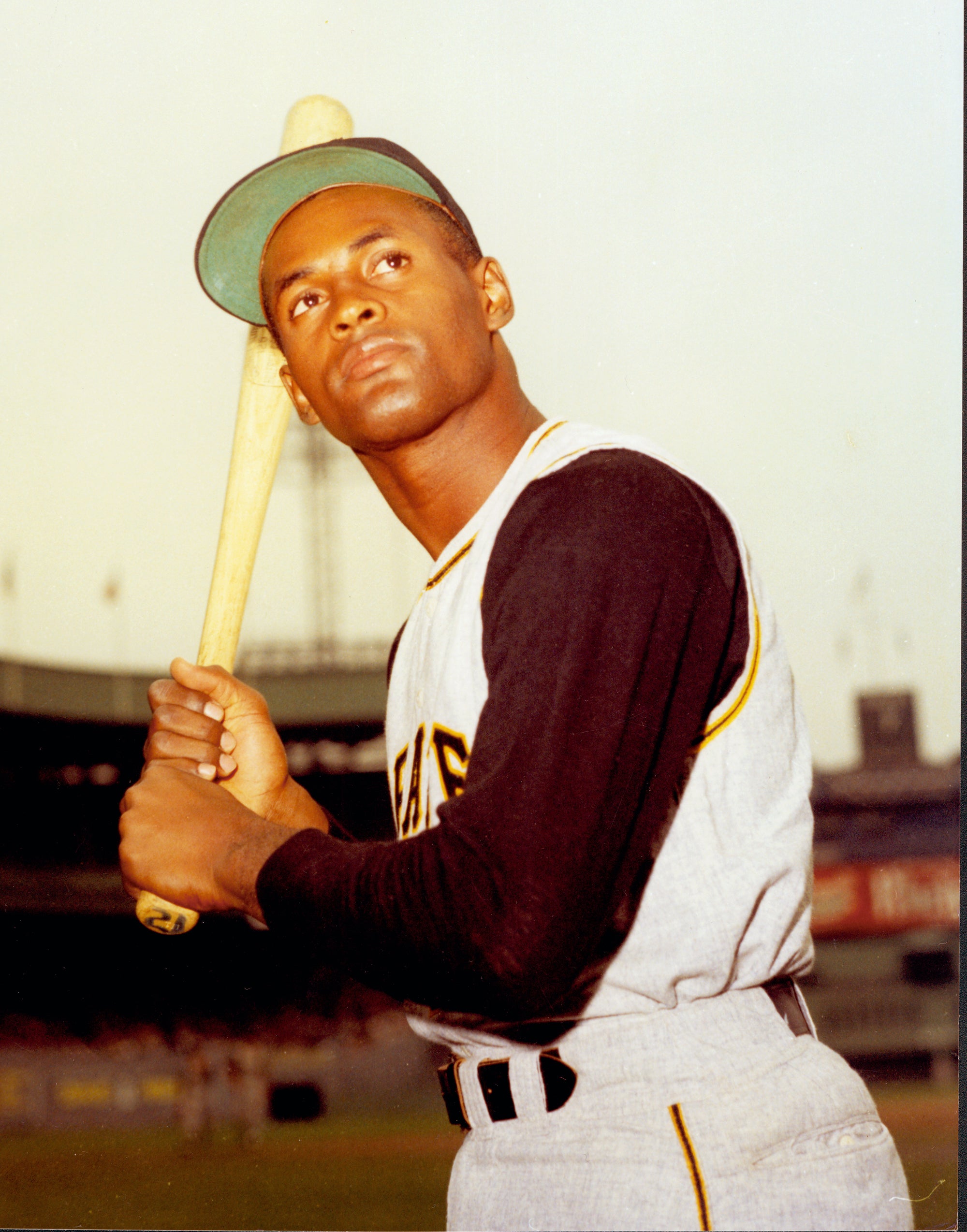

Of all of the individual milestones achieved by Roberto Clemente, a list that includes batting titles, an NL MVP Award and numerous All-Star Game selections, one stands above the rest. It was his long-awaited 3,000th hit. And as no one could have foreseen, that milestone hit turned out to be the final hit of his regular season career.

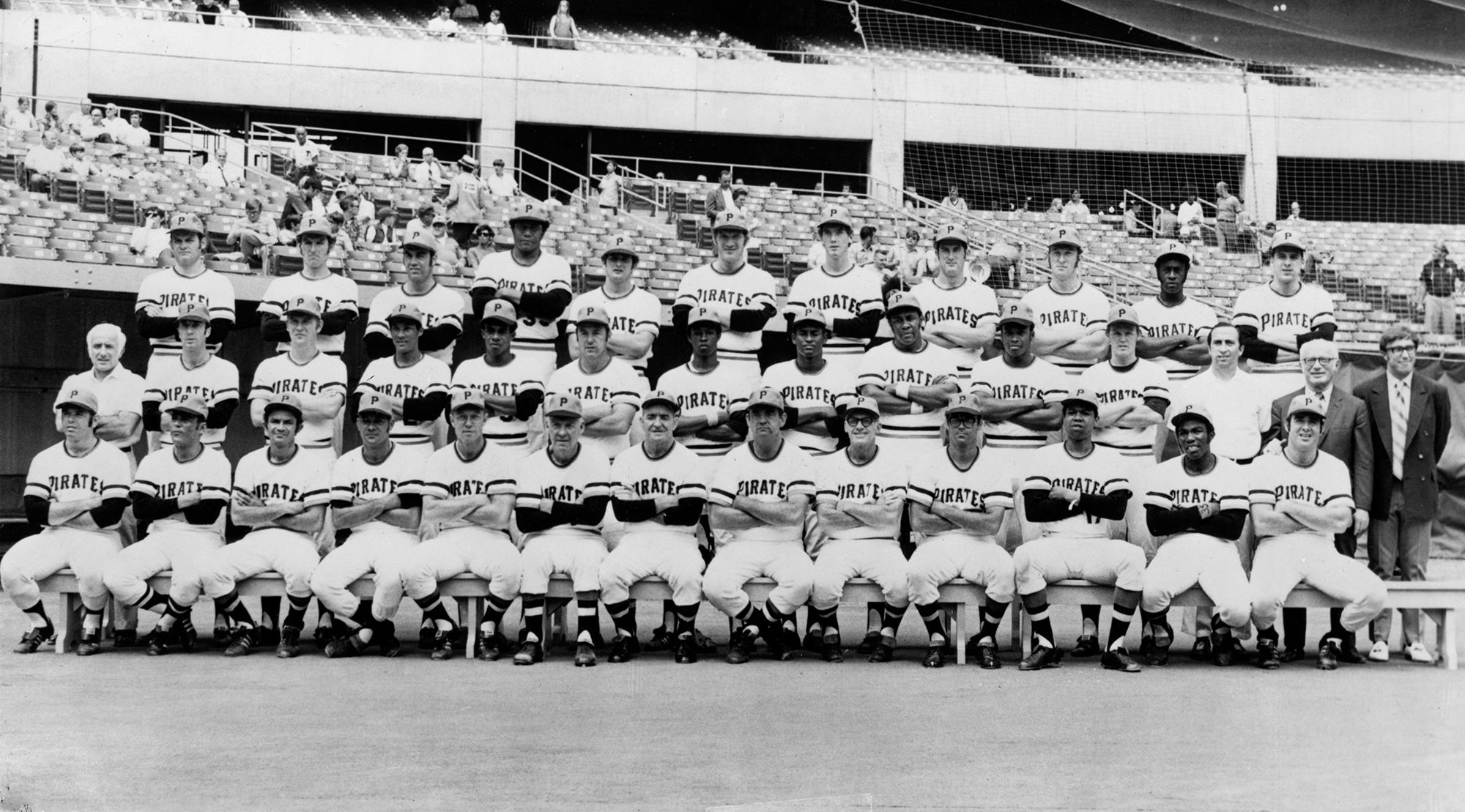

At the beginning of the 1972 season, Clemente and most Pittsburgh Pirates fans thought that he would reach the mark by August, but a spate of injuries limited the veteran outfielder’s playing time that summer. As the Pirates moved into the final days of their regular season schedule in September, it now seemed questionable that Clemente would reach 3,000 at all that season.

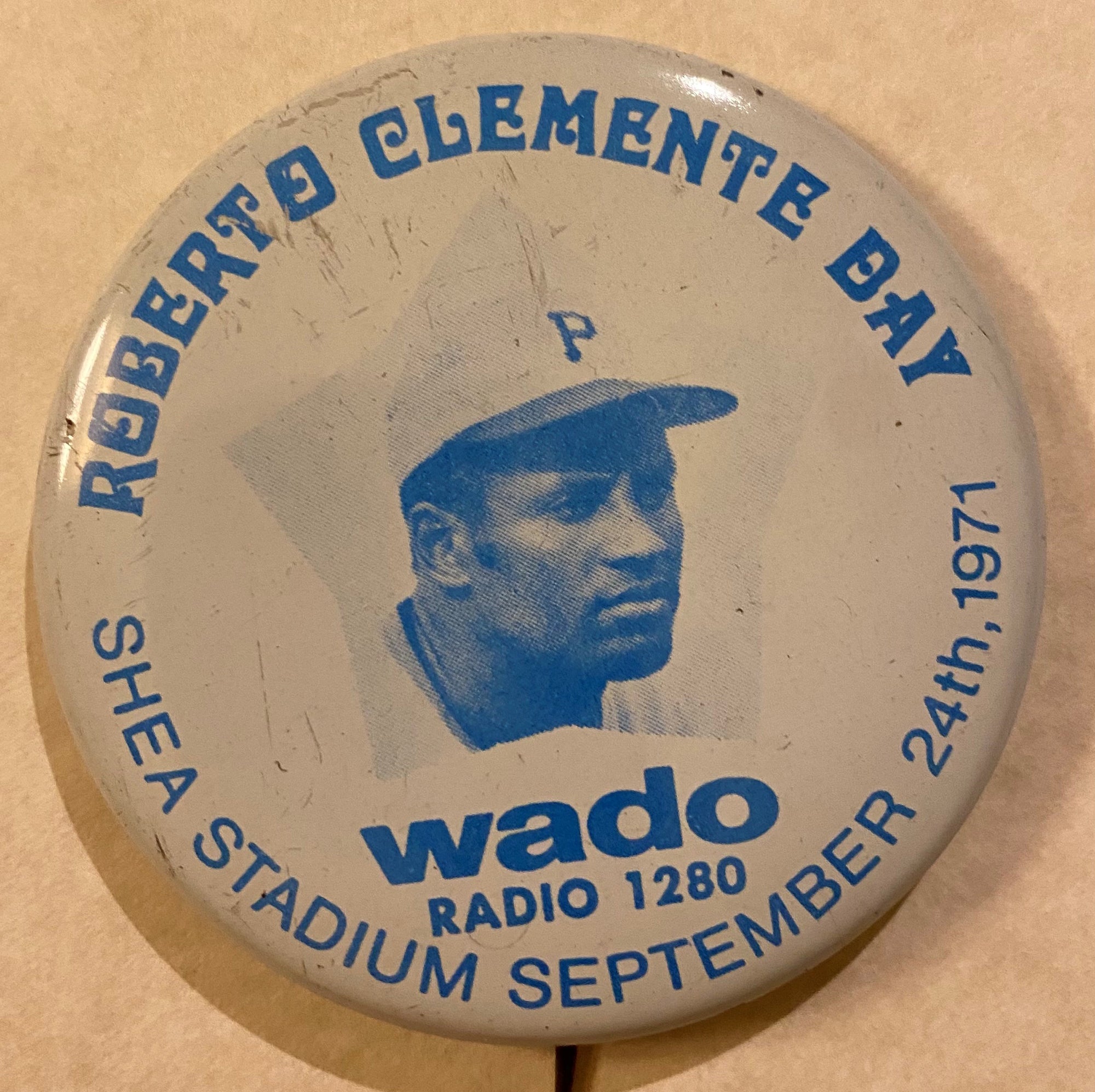

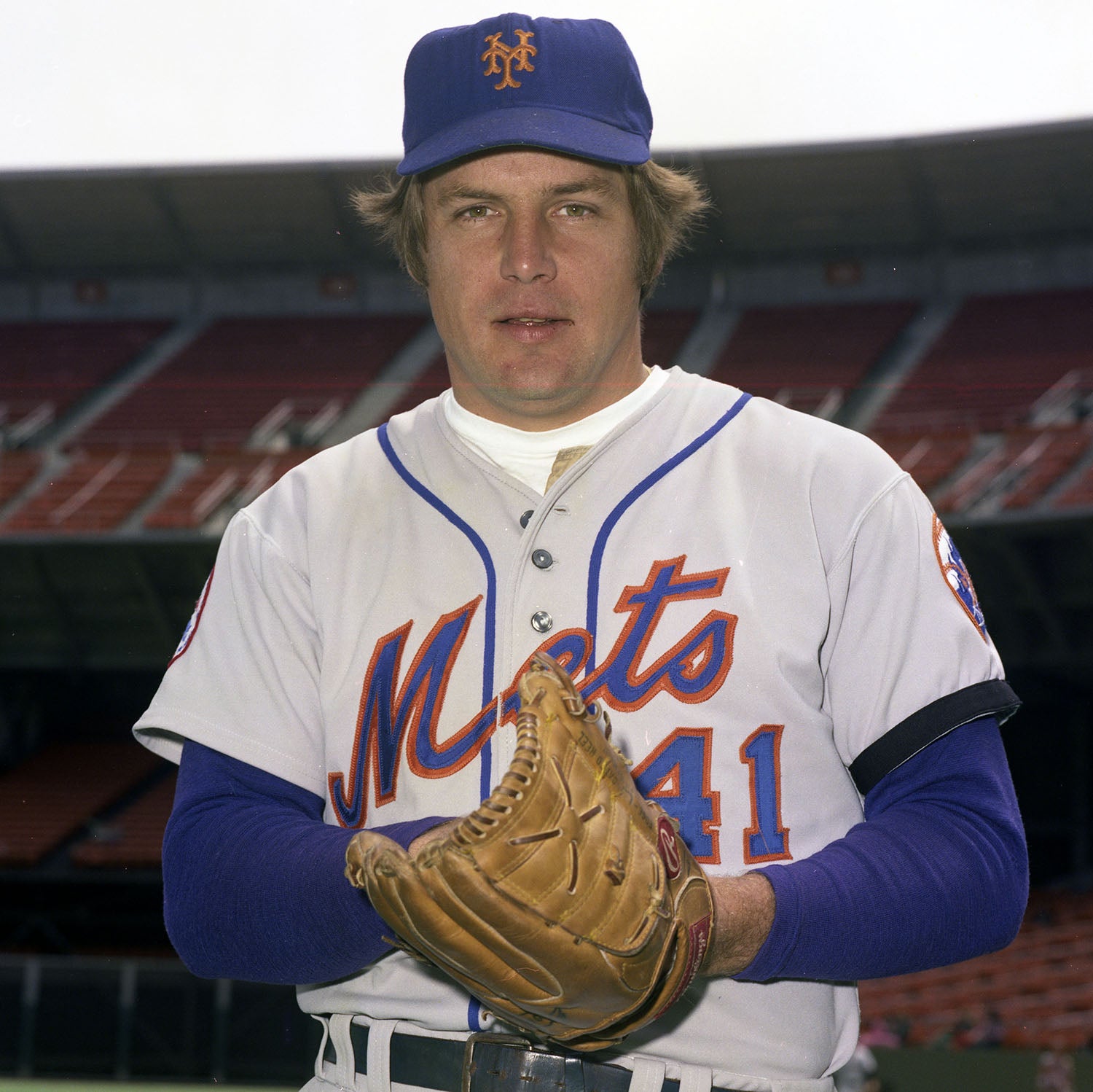

With the Pirates already having clinched the National League East, manager Bill Virdon debated the merits of resting Clemente vs. having him continue an all-out pursuit of 3,000. Clemente, of course, wanted to play. As the Pirates readied to play their final full weekend series of the regular season, he stood at 2,999. Playing at Three Rivers Stadium on a Friday evening, Clemente faced New York Mets ace Tom Seaver and tapped a bouncing ball up the middle. Second baseman Ken Boswell tried to field the grounder, but the ball caromed off his glove. The message on the scoreboard at Three Rivers Stadium almost immediately flashed “Hit”—No. 3,000. The crowd of over 24,000 fans erupted loudly.

Moments later, the scoreboard flashed another message: “E.” That indicated that Boswell, usually a surehanded infielder, had made an error. The fans booed the decision lustily. Official scorer Donald “Luke” Quay, a writer and editor for the McKeesport Daily News, had apparently ruled the play an error from the outset, but the scoreboard operator mistakenly thought that he heard someone in the press box yell, “Hit.” The misunderstanding resulted in a premature celebration by the fans and by Clemente, who had already been presented with the ball by first base umpire, John Kibler.

After the game, Clemente initially expressed frustration with the scoring decision. “It was a hit all the way,” he told reporters in the Pirates’ clubhouse. Clemente believed that Charley Feeney, a longtime writer for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, had made the scoring decision. A few moments later, Clemente learned that it was Quay.

Of all the writers who covered the Pirates, Clemente liked Quay the best. In fact, they were friends. So when Clemente learned that it was Quay who ruled the error, he softened his tone. He was not about to allow a scoring decision affect his friendship. Clemente took the ball and signed it for Quay, while leaving a humorous message for his good friend. “It was a hit,” Clemente inscribed on the first line. On the second line, he wrote, “No, it was an error.” And then came the third line, “No it was superman Luke Quay. To my friend Luke with best wishes—Roberto Clemente.”

Restored to good spirits, Clemente would have to continue his quest for 3,000 the next day – Sept. 30, a Saturday afternoon game. Clemente faced Jon Matlack, an impressive young left-hander who would soon win National League Rookie of the Year honors. In his first at-bat against Matlack, Clemente struck out. He would have to wait for his second chance until the fourth inning.

Clemente led off the fourth against Matlack. While Bob Prince announced the game on the Pirates’ flagship station, KDKA, Luis Mayoral delivered the Spanish language play-by-play for a radio station in Puerto Rico. “It was something like 3:07 in the afternoon,” recalls Mayoral. “A little bit over 13,000 fans were in the stands. Fourth inning. Jon Matlack was pitching. Yes, I saw that.”

Matlack jumped ahead on the count with a first-pitch strike. Then came Matlack’s second pitch, a curve ball. The pitch hung a bit, allowing Clemente to make hard contact, lacing the ball toward the left-center field gap. Neither Mets left fielder John Milner nor center fielder Dave Schneck would have a chance to make the catch. There would be no dispute of hit vs. error on this play. By the time that Schneck retrieved the ball and threw it toward the infield, Clemente easily steamed into second base with a clean, no-questions-asked double.

With that hit, Clemente became the 11th player in major league history to reach the 3,000-hit circle. He also became the first Latino to achieve the milestone.

As Clemente stood atop second base, umpire Doug Harvey retrieved the ball from Mets shortstop Jim Fregosi. Harvey handed the ball to Clemente, shaking his hand during the brief encounter. Clemente then handed the ball off to his first base coach, Don Leppert, who kept the ball in his back pocket for safekeeping.

Although the crowd at Three Rivers Stadium was small that day – only 13,117 in attendance – the fans were loud. They took to their feet and cheered raucously, maintaining the applause for more than a minute. Not knowing what to do next, Clemente awkwardly placed his hands on his hips and rolled his neck, the latter movement a ritual that he often did during his at-bats.

“I feel bashful when I get a big ovation,” Clemente told Milton Richman of United Press International after the game. “I am really shy. I never was a big shot and I never will be a big shot.”

After play resumed, Clemente eventually came around to score as part of a three-run Pirates rally. In the top of the fifth inning, Clemente ran out to right field and received another standing ovation from the fans at Three Rivers.

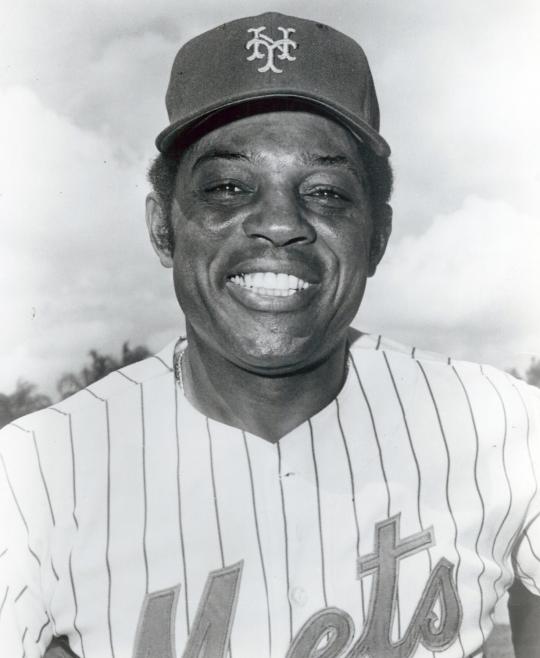

When Clemente and the Pirates returned to the dugout at the end of the half-inning, Clemente received a different kind of acknowledgement. Willie Mays, now a part-time player with the Mets, made his way from the visiting dugout over to the Pirates’ bench. Although Clemente and Mays were never particularly close, they had played together one season in winter ball during the mid-1950s. The two stars clearly respected each other. Mays hugged Clemente, congratulating him on the milestone.

Clemente did not bat again that day. In the fifth inning, with the Pirates on the way to a 5-0 win, Bill Virdon gave Clemente the rest of the day off, pinch-hitting for him with another future Hall of Famer, Bill Mazeroski. After the game, Clemente spoke to reporters and dedicated his 3,000th hit to the fans of Pittsburgh and to a man named Roberto Marin, who had first coached him in softball so many years earlier in Puerto Rico.

No one realized it at the time, but Clemente’s 3,000th hit would be the last regular season hit of his career. Virdon rested Clemente on Sunday, played him only in the field in a Tuesday game, and then sat him out on Wednesday, the final day of the regular season.

Clemente would collect four more hits during a disappointing National League Championship Series loss to the Cincinnati Reds, but since those hits came in the postseason, they would not count toward his career total.

Then came the tragic fates of winter. The New Year’s Eve mission of mercy to Nicaragua ended in a plane crash, killing five men, including Clemente, who was just 38. Clemente had planned to play one final season for the Pirates before embarking on a post-playing career that might have involved public service in government, or perhaps even a second career in baseball as a manager.

The year of 1972, which had started with such promise, turned out to be the last of Clemente’s life. It was also our last chance to watch his remarkable brilliance, exemplified on the day that he reached the milestone of 3,000.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum