- Home

- Our Stories

- Paige’s induction in 1971 changed history

Paige’s induction in 1971 changed history

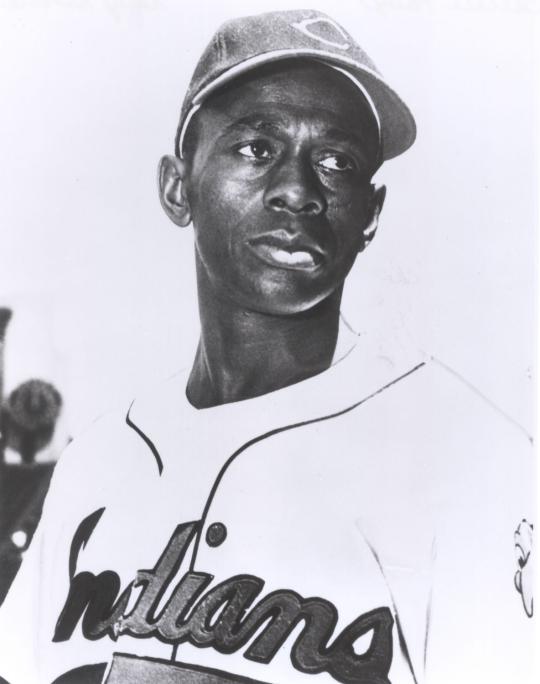

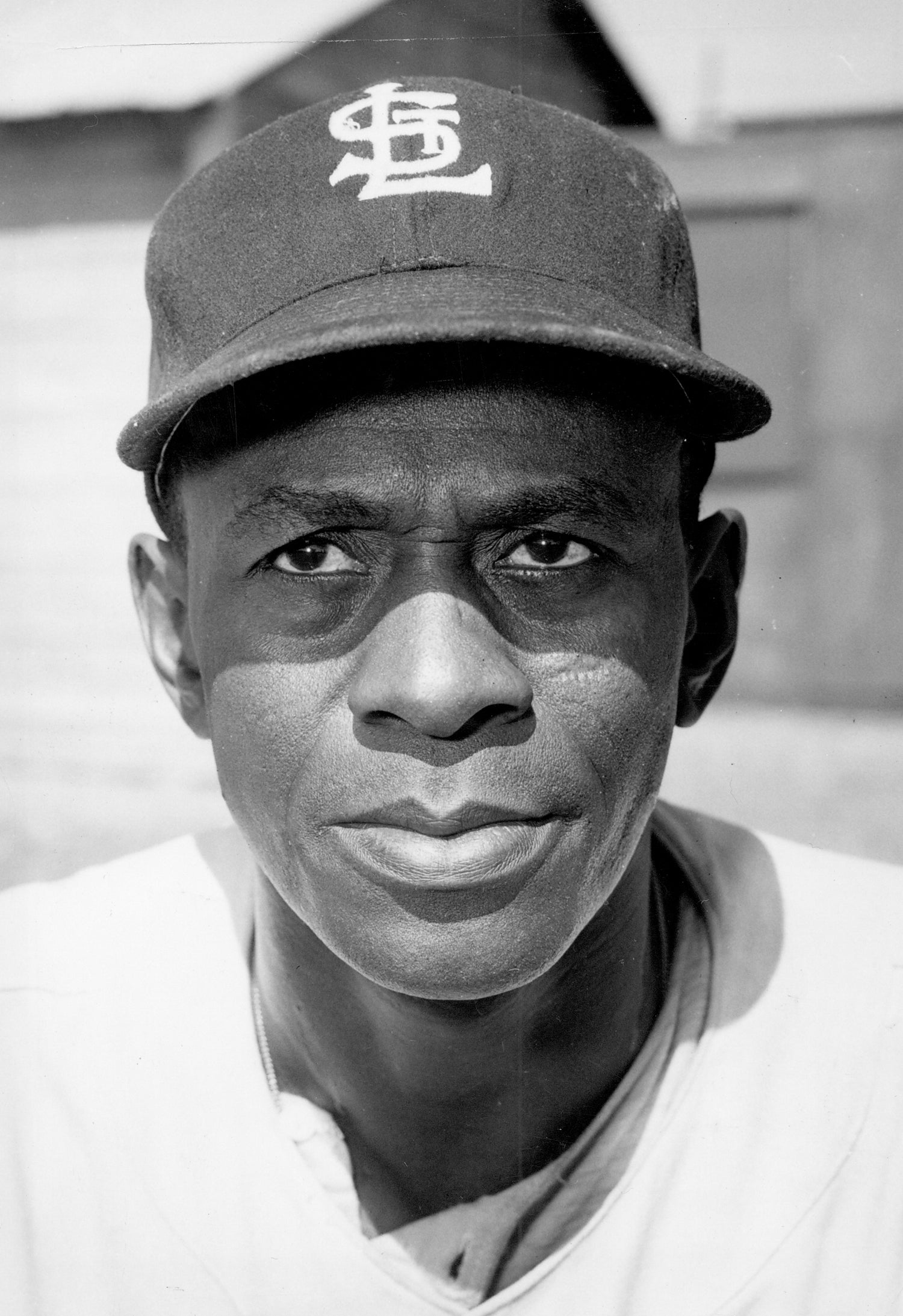

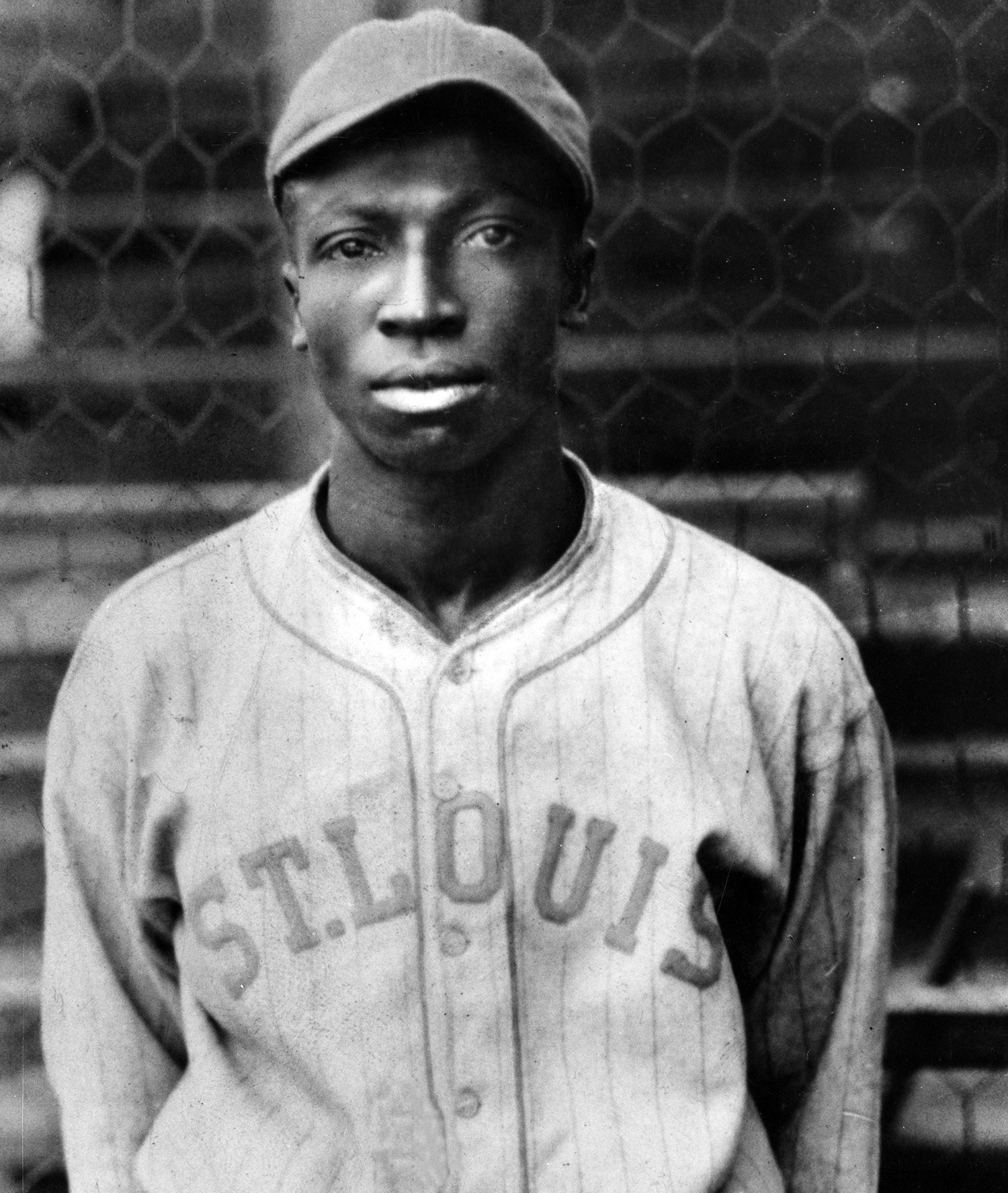

When Satchel Paige made history as the first ballplayer elected to the Hall of Fame based solely on time spent in the Negro Leagues, a new era began in Cooperstown.

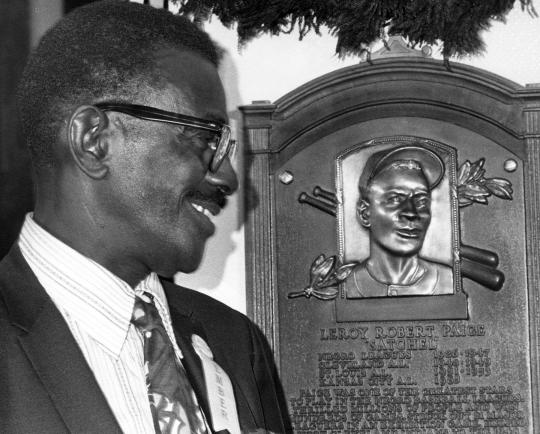

“I am the proudest man on the earth today,” said the ageless right-hander on Aug. 9, 1971 as part of his induction speech that ended with a bronze plaque in the hallowed halls of Cooperstown, “and my wife and sister and sister‐in‐law and my son all feel the same. It's a wonderful day and one man who appreciates it is Leroy ‘Satchel’ Paige.”

While the Hall of Fame already included such Black stars as Jackie Robinson and Roy Campanella – former Negro League players who starred in the formerly segregated big leagues for 10 seasons apiece – the road to baseball immortality was bumpy for the supposed 65-year-old Paige (who refused to reveal his actual age).

Arguably the biggest drawing card in Black baseball, the lanky and legendary Paige starred on pitching mounds from Canada to the Dominican Republic. From the late 1920s through the 1940s, his time with the Birmingham Black Barons, Pittsburgh Crawford and Kansas City Monarchs enhanced the natural showman’s appeal to the fans. And stints with the Cleveland Indians and St. Louis Browns while in his 40s exposed him to a new audience.

Many have claimed it took the words of Ted Williams, the great Boston Red Sox slugger, as part of his Hall of Fame induction speech on July 25, 1966, to provide the impetus for change as for as Cooperstown recognition for the Negro League stars such as Paige.

Speaking for those without a voice, those who had been shunted aside, those with little hope of ever joining the National Pastime’s fabled fraternity, Williams said: “Inside this building are plaques dedicated to baseball men of all generations and I’m privileged to join them…And I hope that someday the names of Satchel Paige and Josh Gibson in some way can be added as a symbol of the great Negro players that are not here only because they were not given a chance.”

Hall of Famer and Negro League veteran Monte Irvin once said, “(Williams’) speech had an impact. He did change some minds. The writers picked up on it, and some of the powers-that-be at the Hall of Fame had to kind of perk up and take notice.”

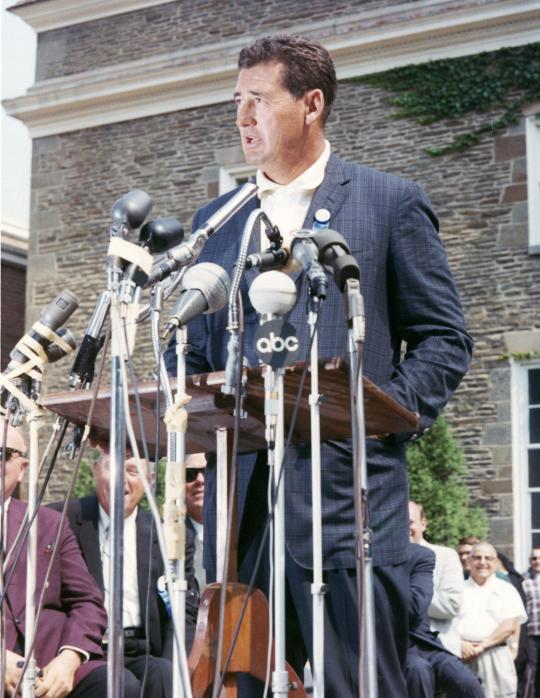

The Baseball Writers’ Association of America, the group that annually votes on major league players for Hall of Fame inclusion, would later take up the cause. At the 1969 Hall of Fame Induction Ceremony, BBWAA President Dick Young, who would earn the BBWAA’s Lifetime Achievement Award in 1978, spoke eloquently on the subject before thousands of spectators.

“Until now, there has been one failing, and the baseball writers intend that this should be rectified,” Young said. “Nobody questions, certainly, the credentials of these great ballplayers on my right. They all belong. But we do ask the question, why should Waite Hoyt and Stanley Coveleski be in the Hall of Fame and not Satchel Paige? Why should Roy Campanella be in the Hall of Fame and not Josh Gibson?

“There are other men, great ballplayers, who certainly have a place here in this shrine. They were not part of organized ball. When the rules were set up, one of the rules was that you should excel for a period of 10 years because time proves a man’s worth. And it might be said that Satchel Paige did not play major league ball for 10 years and that Josh Gibson did not play major league ball for 10 years. But was that their fault, gentlemen? The answer, of course, is obvious.”

The cause became reality on Feb. 3, 1971, when Commissioner Bowie Kuhn announced the formation of a special 10-man committee, the Committee on Negro League Veterans, which included Roy Campanella, Judy Johnson and Monte Irvin, to select the top Negro League stars of the pre-1947 era “as part of a new exhibit commemorating the contributions of the Negro leagues to baseball.” But they weren’t to be actual Hall of Famers because they didn’t play major league ball for the required 10 seasons.

Plaques honoring these Negro league stars were to be in a “special” wing from the existing 117 Hall of Fame plaques at the time.

“I wouldn’t call it a compromise,” Kuhn said. “The rules for selection to the Hall of Fame are very strict and I think those standards are correct. Through no fault of their own, these stars of the Negro Leagues didn’t have major league exposure.

“The purpose here is to recognize the great contributions made by the Negro Leagues and I think the stars should be identified and recognized by the public.

“The Hall of Fame is not segregated. In addition to being a brick building, it’s a state of mind.”

Allowed to choose one player per year, the Committee unanimously selected Paige on Feb. 9, 1971.

“I don’t feel segregated,” said Paige at a press conference that day. “I’m proud to be wherever they put me in the Hall of Fame.

“Every year I played, I said that was my best year. I know this is my best year.”

Not all agreed.

“If the blacks go in as a special thing, it’s not worth a hill of beans. It’s the same rotten thing all over again,” said Hall of Famer Jackie Robinson, the player who broke down big league baseball’s color barrier in 1947. “They deserve to be in it but not as black players in a special category. Rules have been changed before. You can change rules like you change laws if the law is unjust.”

And the rules were changed, with approval by the Hall of Fame board of directors, with Kuhn and Hall of Fame President Paul Kerr announcing on July 8, 1971, that Paige and future inductees would be given full membership.

“I was just going along with the program and I didn’t have no kick or no say when they put me in that separate wing,” Paige said, “but getting into the real Hall of Fame is the greatest thing that ever happened to me in baseball.

“All we players in the Negro Leagues could do was hear about the Hall of Fame. Now it’s real.”

The Committee on Negro League Veterans, which disbanded in 1977, would subsequently elect Josh Gibson, Buck Leonard, Monte Irvin, “Cool Papa” Bell, Judy Johnson, Oscar Charleston, Martin Dihigo and Pop Lloyd.

So it was on Aug. 9, 1971, five years and two weeks after Williams made his bold pronouncement, that Paige did indeed became a Hall of Famer.

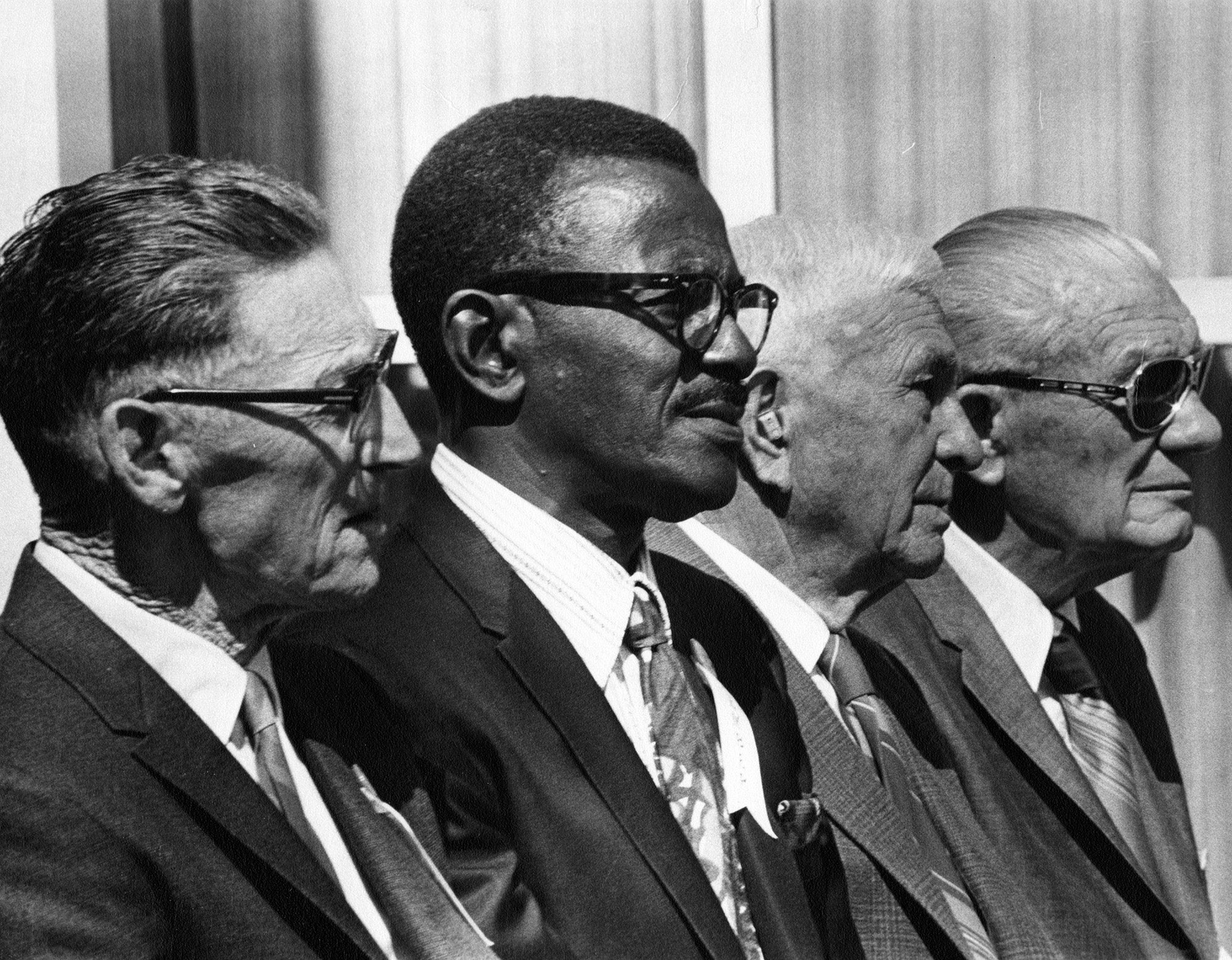

On a stage constructed outside the Hall of Fame Library, and with approximately 2,500 fans stretched out on the grass in Cooper Park, Paige entered the sport’s most exclusive fraternity along with Dave Bancroft, Jake Beckley, Chick Hafey, Harry Hooper, Joe Kelley, Rube Marquard and George Weiss.

“The institutions of man ultimately come down to people, to their achievements and their failures, their glories, their tragedies, their charm, and their peculiarities,” said Baseball Commissioner Bowie Kuhn. “Baseball glories and revels in its people, more so than any institution I know of. The ultimate glory of baseball is Cooperstown, the glory is the Hall of Fame and its members. The greatest day of the baseball year is this day when we honor anew the incomparable champions of our national pastime.

“There are only 126 members from the day it began. This then is the ultimate glory of baseball, this then is Bancroft and Beckley and Hafey and Hooper and Kelley and Marquard and Paige and Weiss.”

Paige’s brief induction speech alternated between humorous and serious.

“Since I've been here I've heard myself called some very nice names,” Paige said. “And can remember when some of the men in there called me some bad names when I used to pitch against them.”

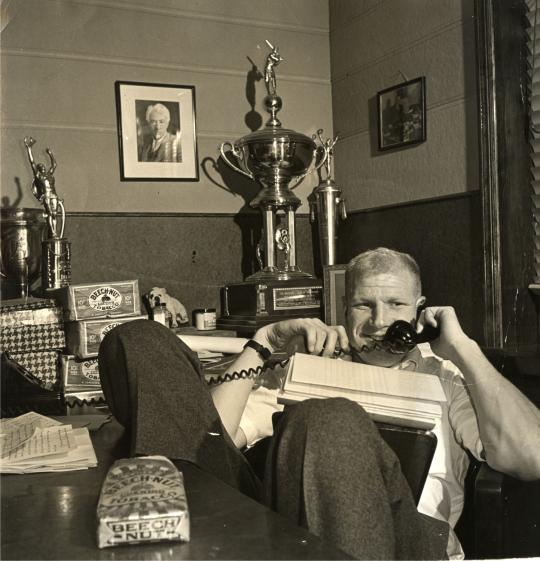

And Bill Veeck, who attended the festivities, was thanked for bringing Paige to the “majors” in 1948.

“Then there was that fellow who got my age mixed up when he called me to Cleveland,” Paige said. “They told him to get anyone but Paige — he's too old to vote. When you got me, they was fixin’ to run us both out of Cleveland, if I didn’t do well. Well, Mr. Veeck, I got you off the hook today.”

And, as always, Paige’s reputed age was a topic.

“I don’t think we’ll ever get that straightened out. I got my birth certificate with me, but they won’t accept that,” he said. “They got my age mixed up when I went to Cleveland, and now they say the guy in Alabama (where Paige was born) gave me the wrong certificate.”

Today, inside the Hall of Fame’s Plaque Gallery, Paige’s bronze plaques reads: “Paige was one of the greatest stars to play in the Negro Baseball Leagues. Thrilled millions of people and won hundreds of games. Struck out 21 major leaguers in an exhibition game. Helped pitch Cleveland Indians to the 1948 pennant in his first big league year at the age 42. His pitching was a legend among major league hitters.”

Bill Francis is the senior research and writing specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum