- Home

- Our Stories

- Radio Days

Radio Days

This story is excerpted from the book Memories from the Microphone: A Century of Baseball Broadcasting, which is available to pre-order by clicking here.

An old British Broadcasting Company radio series, Listen With Mother, began each program by asking, “Are you sitting comfortably? Then I’ll begin.”

On Friday, Aug. 5, 1921, baseball on the air began commercially, if not always comfortably, over America’s first licensed radio station, Pittsburgh’s KDKA. More than a century of the pastime has now been ferried to the republic through the air by the wireless, as it was first known, and later television.

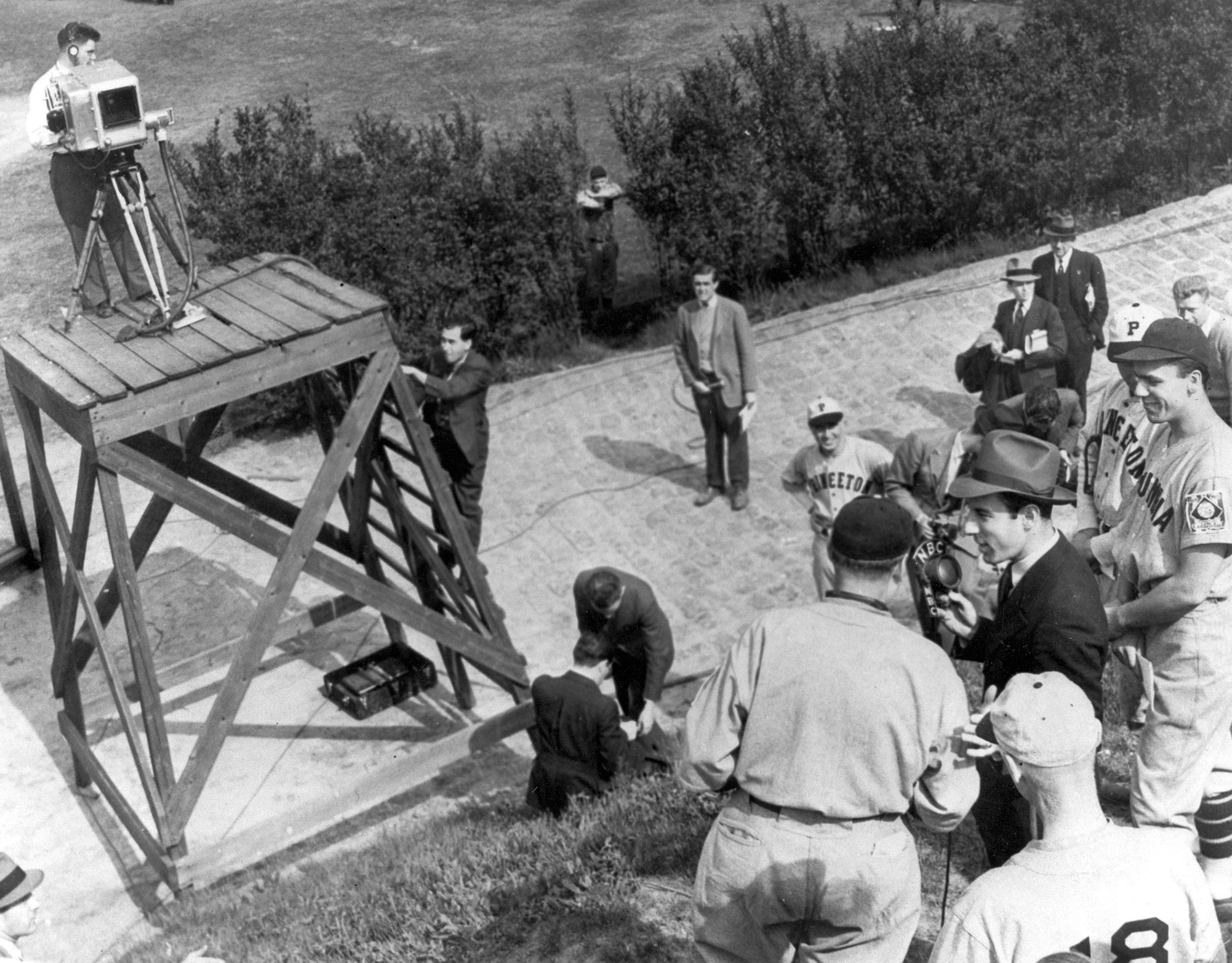

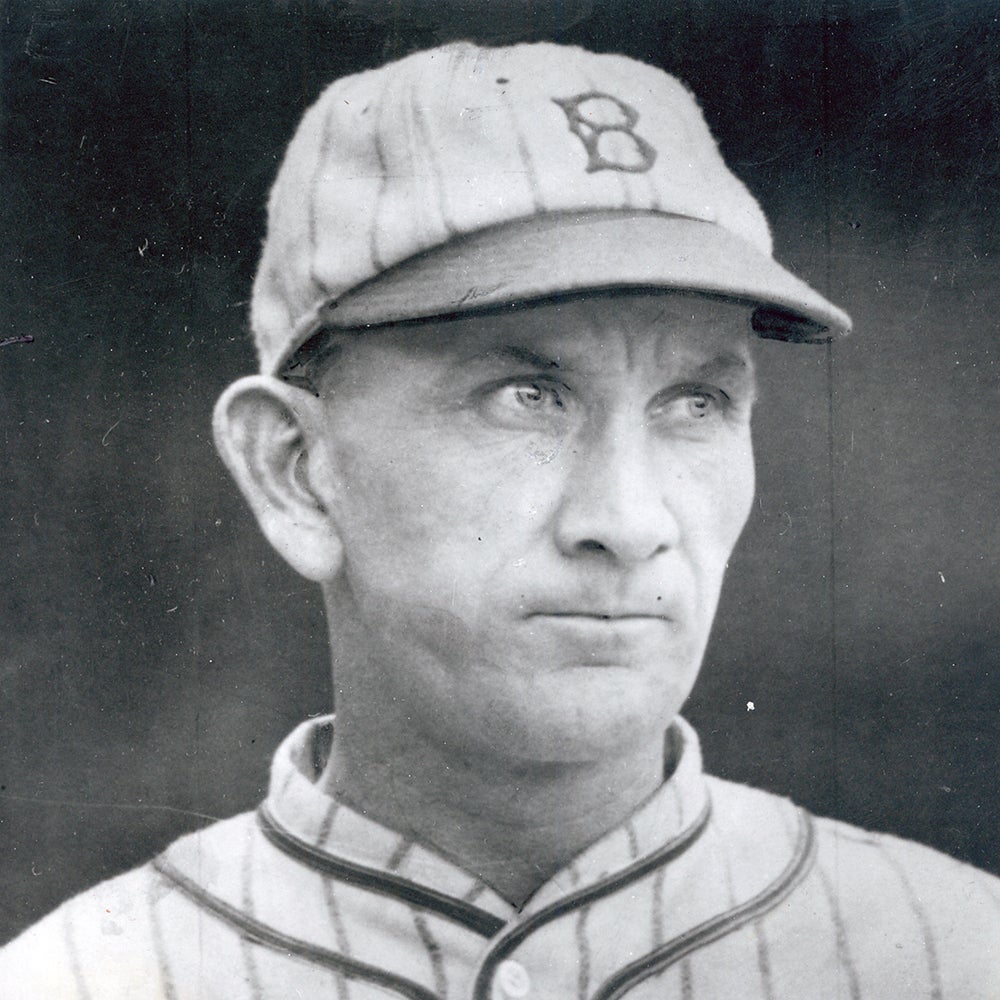

Since baseball has long seemed wed to both, it is natural to assume that it must have long been in harmony with each. In fact, Harold Arlin was winging it that August afternoon at Forbes Field in suburban Pittsburgh as he described the first major-league baseball game ever broadcast – play-by-play, carried by a microphone – inventing an art form as he spoke.

After that game’s final pitch – Pittsburgh 8, Philadelphia 5 – Arlin’s voice was critiqued by a listener as “clear, crisp, resonant, and appealing.” In time, as “The Voice of America,” it made him what The London Times called “the best-known American voice in Europe”, indeed “the world’s most popular radio announcer.” He also invented the celebrity interview in the 1920s, emerging for a while as a celebrity himself.

Such a future would have seemed more improbable than the sheer fact of radio – sound, through the air! – when Arlin, 25, and several other Westinghouse Electric and Manufacturing engineers visited the company’s KDKA rooftop East Pittsburgh studio in 1920. “What’s that?” Harold had said several days earlier, eying the shack studio from outside the plant. Inside, he now saw a microphone about which the same question could be posed.

“It looked like a tomato can with a felt lining. We called it a mushophone.”

Earlier that day, Tuesday, Nov. 2, KDKA received a broadcast license as the first commercial radio station: thus, eligible to broadcast. Moreover, it had a lot to announce – since the date was Election Day, KDKA’s on-air debut reporting Warren Harding’s presidential landslide win over James M. Cox. According to The New York Times, “curiosity led Arlin” to apply for the on-air job. He was hired, instantly.

Arlin was born in La Harpe, Ill., raised in Carthage, Mo., and schooled at the University of Kansas. In an exquisitely small field, he was starting at the top. In 1921, Harold did Davis Cup tennis, aired West Virginia-Pittsburgh football and gave baseball scores. On Aug. 5, 1921, needing other programming, he drove to the city’s Oakland section, bought a seat at Forbes Field, put a scorecard on a wooden plank, and converted a telephone to microphone.

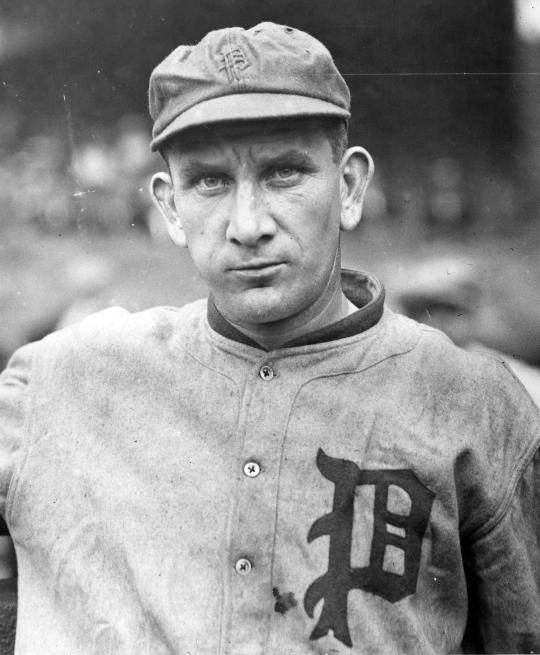

What did the pathfinder sound like that afternoon? KDKA then had only one-hundred-watt power v. today’s 50,000 watts that takes it around the world (AM radio signals bounce around the globe after the sun goes down). Few people had a wireless. The transmitter did or didn’t work. The crowd often drowned Arlin out. No one knew who listened, or how long. The game itself lurched: first inning, Phillies, 4-2, on Cy Williams’ homer; Pirates, 5-4; the Phils tied at five; eighth-inning singles give Pittsburgh the W. Thirteen runs on 21 hits careened around the yard, including three Pirates doubles and a triple.

The game took one hour and fifty-seven minutes.

Ironically, Cox’s 1920 running-mate was Franklin D. Roosevelt, the 1933-1945 president for whom, coining the famed Fireside Chat, his favorite medium was radio and its baseball premiere his kind of game: “lots of action for my money.” Forbes was also his kind of place, letting “outfielders scramble and men run the bases.” Left and right field originally loomed 360 and 376 feet from the plate, respectively. A gargantuan in-play flagpole in center field stood 462 feet away.

Four years earlier, legendary shortstop Honus Wagner had retired. In 1920, Pie Traynor debuted, a stalwart at third. A local saying went: “So and so doubled down the left-field line, and Traynor threw him out.” His plot of grass lay adjacent to the University of Pittsburgh’s Cathedral of Learning and scenic Schenley Park – to Sports Illustrated, “the loveliest setting of any major-league field.” Added Reach Baseball Guide of Forbes Field: “It has not its superior in the world.”

Daily Arlin saw a “tub load to describe,” but no one had even “told me I had to talk between pitches,” he said. “Our guys at KDKA didn’t think that baseball would last on radio. I did it sort of as a one-off project.”

As station wattage leapt, so did his marquee. His news show on the station—another first – starred such celebrities as French general Ferdinand Foch, British statesman David Lloyd George, movie star Lillian Gish and then-Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover.

One 1920s day a rather eminent baseball player in Pittsburgh for an exhibition game agreed to appear on air. At the William Penn Hotel studio, Babe Ruth even found a speech written for him. Introduced by Arlin, the man George Will called “the first national superstar, the man who gave us that category,” found himself unable to say a word.

Desperate, Harold took the speech and started reading it as if he were Babe Ruth. As he did, the Bambino silently leaned against the wall, sweating and smoking one cigarette after another. “We pull it off,” Arlin said, letters to KDKA hailing Babe’s calm, assured voice. Harold’s task became to find time to broadcast as much baseball as he would like, airing the Pirates sporadically through 1924, both pleasance and pioneer.

“I was [later] a foreman by day,” he said, “and I’d do KDKA at night.” In 1923, Arlin made the first shortwave broadcast to Great Britain, South Africa, and Australia. In 1925, Westinghouse transferred him to a personnel job in Mansfield, Ohio. A writer said: “To thousands, he seems almost a member of the family.” By now, more than one million Americans owned a receiver.

“TV leaves nothing to the imagination,” Harold said. His medium, on the other hand, left all.

On Election day 1952, KDKA asked Arlin to reminisce about Harding-Cox and report that night’s Dwight Eisenhower-Adlai Stevenson result. Twenty years later the Pirates held a Day in his honor, team play-by-play icon Bob Prince having him broadcast to listeners grown old. Aptly, grandson Steve Arlin pitched for the San Diego Padres, that day’s Pittsburgh rival. Yet it is an incident from a quarter-century earlier that best showed Harold’s mix of modesty and steel.

In 1947, many in Mansfield wanted to name its high school football stadium “Arlin Field.” For more than an hour, the school board, which he served as president, argued the merits, Harold strongly and futilely against. Years later the board’s vote still upset him because it was “one of the few times in my life that no one would listen to me.”

The once “Voice of America” died March 14, 1986, at 90, in Bakersfield, Calif. Many obituaries praised “the man who started play-by-play.”

Curt Smith, to USA Today “the voice of authority on baseball broadcasting,” is the author of more than a dozen books. A former Speechwriter to President George H.W. Bush, he is a Gannett News Service columnist and Senior Lecturer of English at the University of Rochester.