- Home

- Our Stories

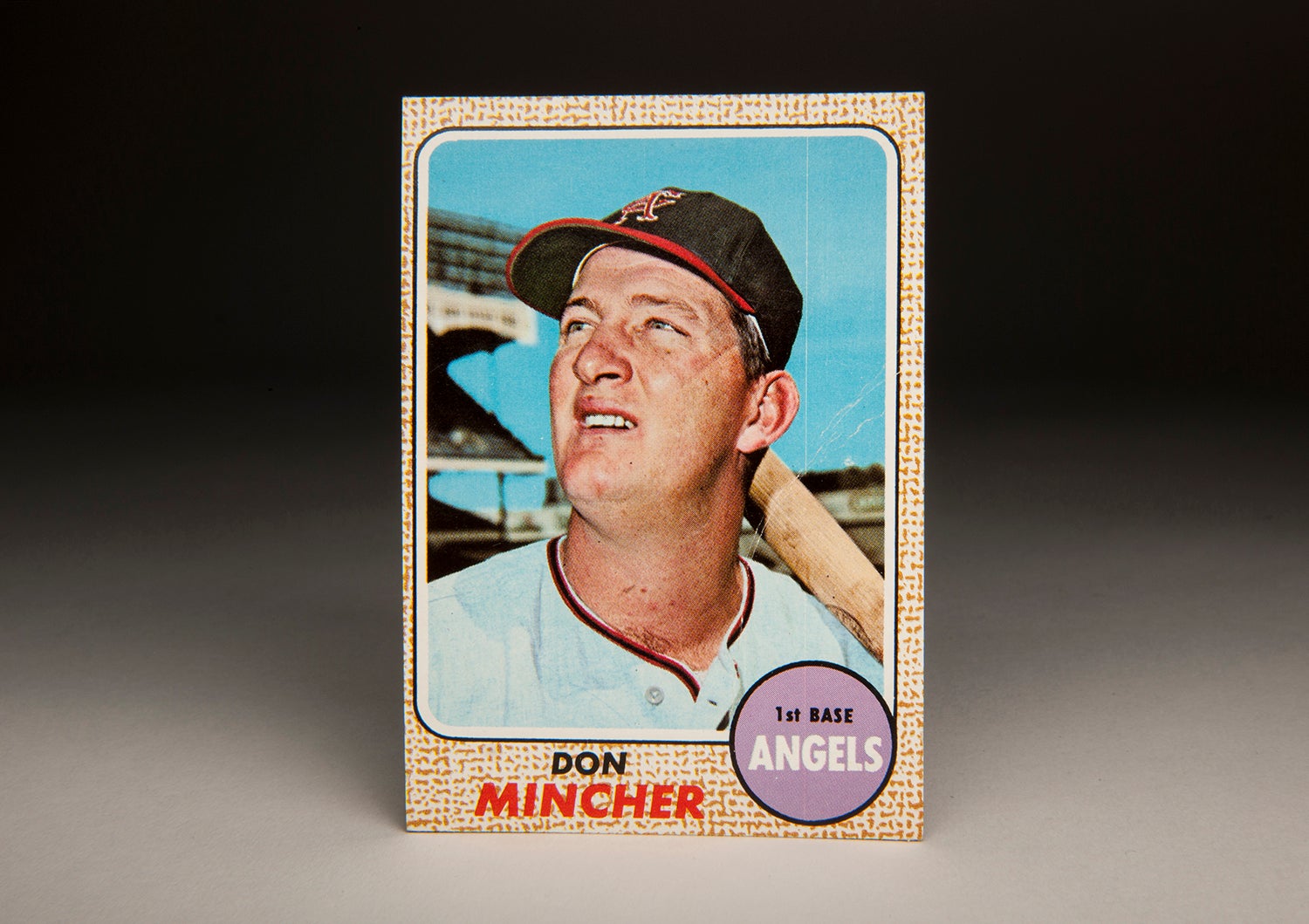

- #CardCorner: 1968 Topps Pete Ward

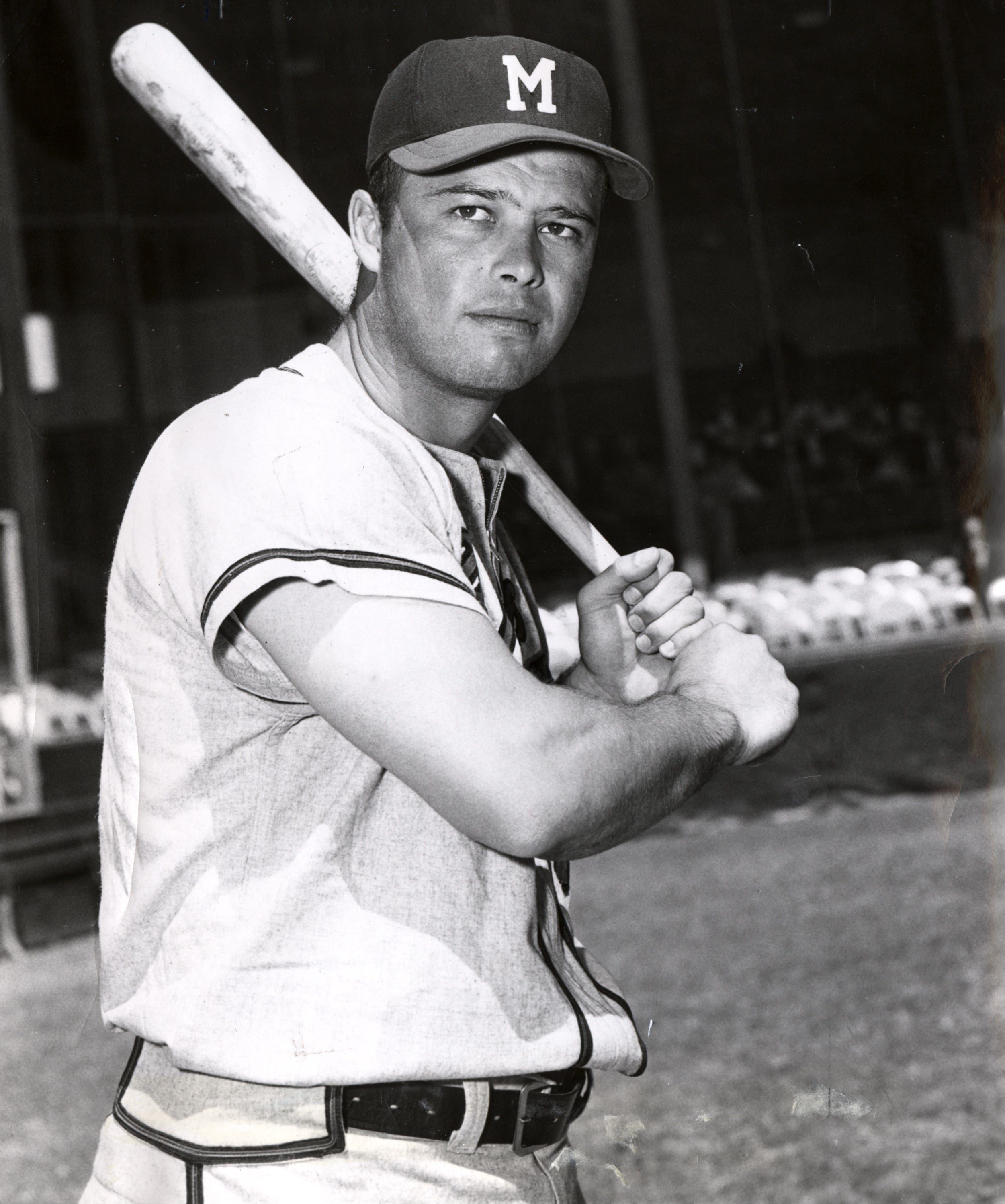

#CardCorner: 1968 Topps Pete Ward

In 1968, The Andy Griffith Show came to an end after an eight-year run, despite still being the most-watched television show in the country. The half-hour comedy, set in the fictional rural town of Mayberry, N.C., featured a beloved set of characters, from the bumbling deputy, Barney Fife (Don Knotts), to the scene-stealing barber, Floyd Lawson (Howard McNear), to the central figure of the show, the virtuous Sheriff Andy Taylor (Andy Griffith).

America loved those characters – and just about everything else about Mayberry.

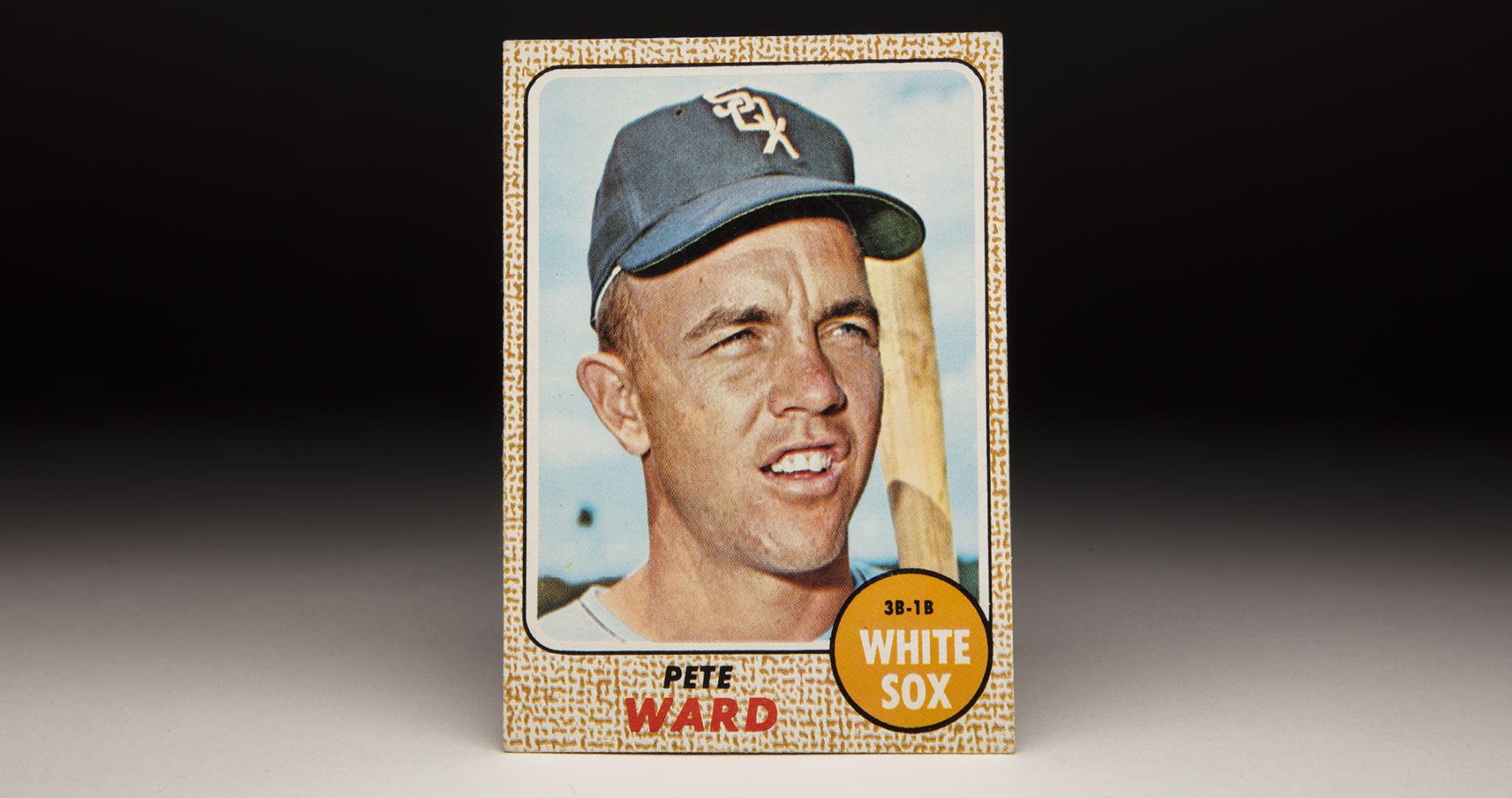

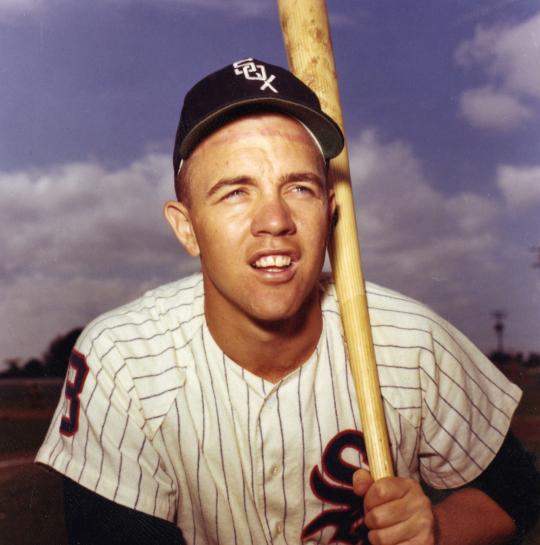

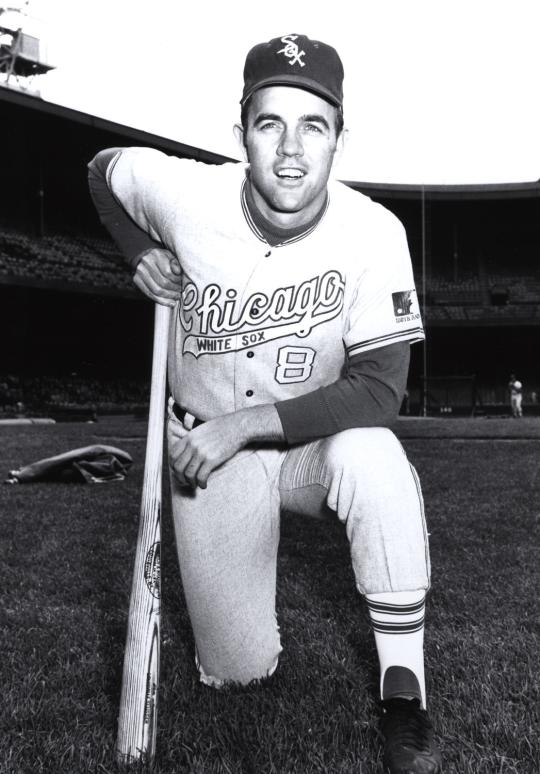

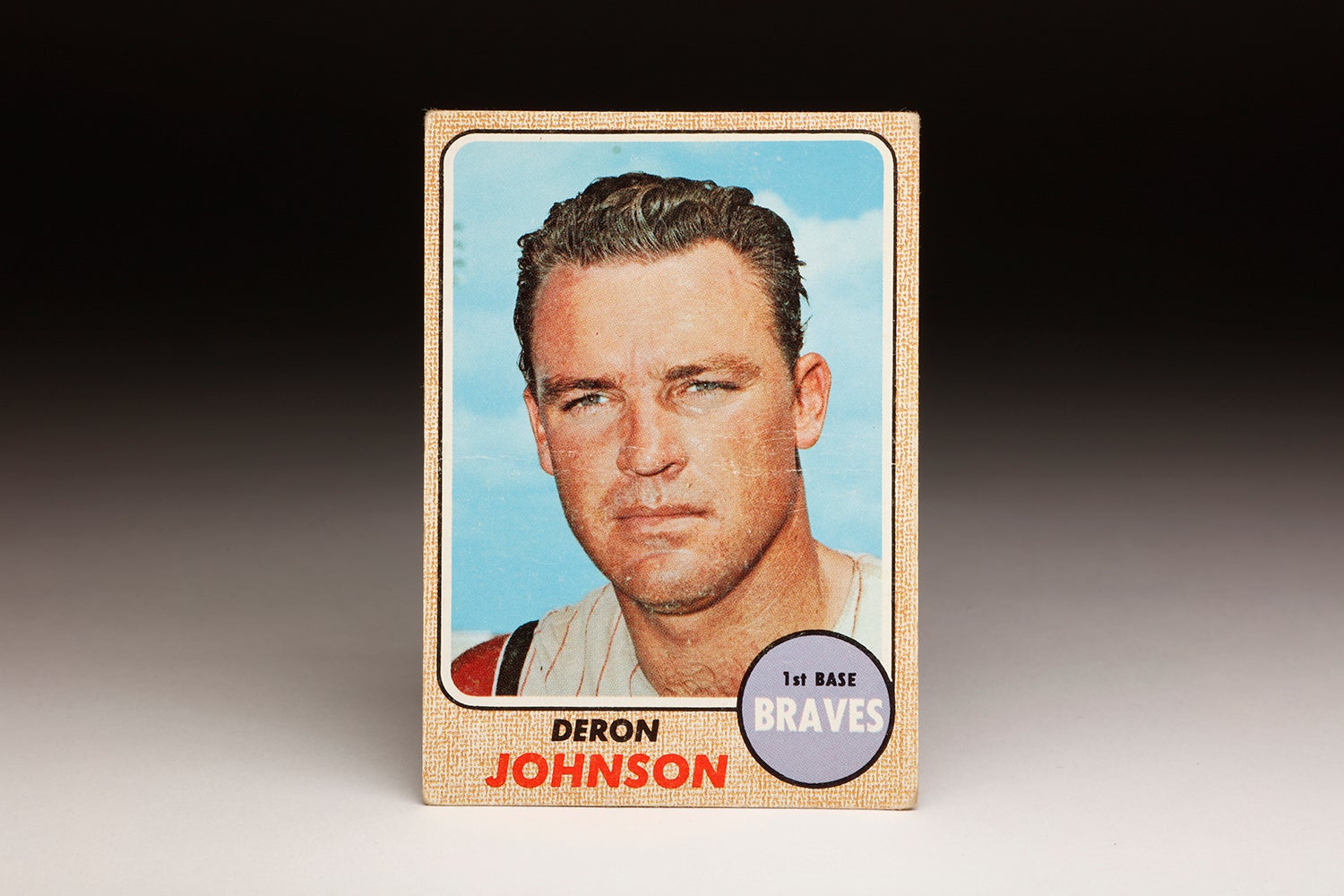

The same year that The Andy Griffith Show departed the CBS airwaves, the Topps Company released this card of Chicago White Sox third baseman Pete Ward. Based on his country boy appearance, young Pete looked like he would have fit in nicely on The Andy Griffith Show. With his squinting eyes, a large set of teeth, and his mouth curled into an “Aw shucks” kind of expression, Ward would have blended in seamlessly at Gomer’s Gas Station, at the Mayberry Diner, or at Floyd’s Barbershop, where Mr. Lawson would have regaled him with his hysterical ramblings about life, love and philosophy.

In reality, Pete Ward was not a country boy. He did not hail from North Carolina, or any part of the American South, for that matter. No, he was from the North – from Canada, to be more specific. He was born in the large Canadian city of Montreal, a place very different from Mayberry, but one that did not yet have a major league team.

The son of former NHL player Jimmy Ward, Pete and his family moved to Portland, Ore., so that the elder Ward could pursue a coaching opportunity. Pete attended Jefferson High School, located within the city limits. From there, Ward went to college, but he remained in Portland, matriculating at Lewis and Clark College. To this day, he is one of only two alumni of Lewis and Clark to make the major leagues.

Ward is one of those players who has seemingly become overlooked by the baseball mainstream. Unless you grew up with the game in the 1960s and early 1970s, it’s quite possible you have never heard of Pete Ward, much less know anything of substance about him. But at one time, Ward looked like a budding Hall of Famer, a kind of Eddie Mathews in-the-making. A left-handed hitting third baseman with power, Ward put up huge offensive numbers in his first two full seasons, narrowly missing out on a Rookie of the Year Award and twice finishing in the top 10 of American League MVP voting.

And then, as with so many other players, Ward’s career took a sudden and unwanted turn. He would never again match the statistics from his first two years with the White Sox. His career, as promising as it once seemed, would not even last 10 seasons. By his 32nd birthday, Ward was out of baseball. These are all reasons why Ward is somewhat forgotten today. But his story, as with so many players who faced obstacles and hardships, is worthy of a second look.

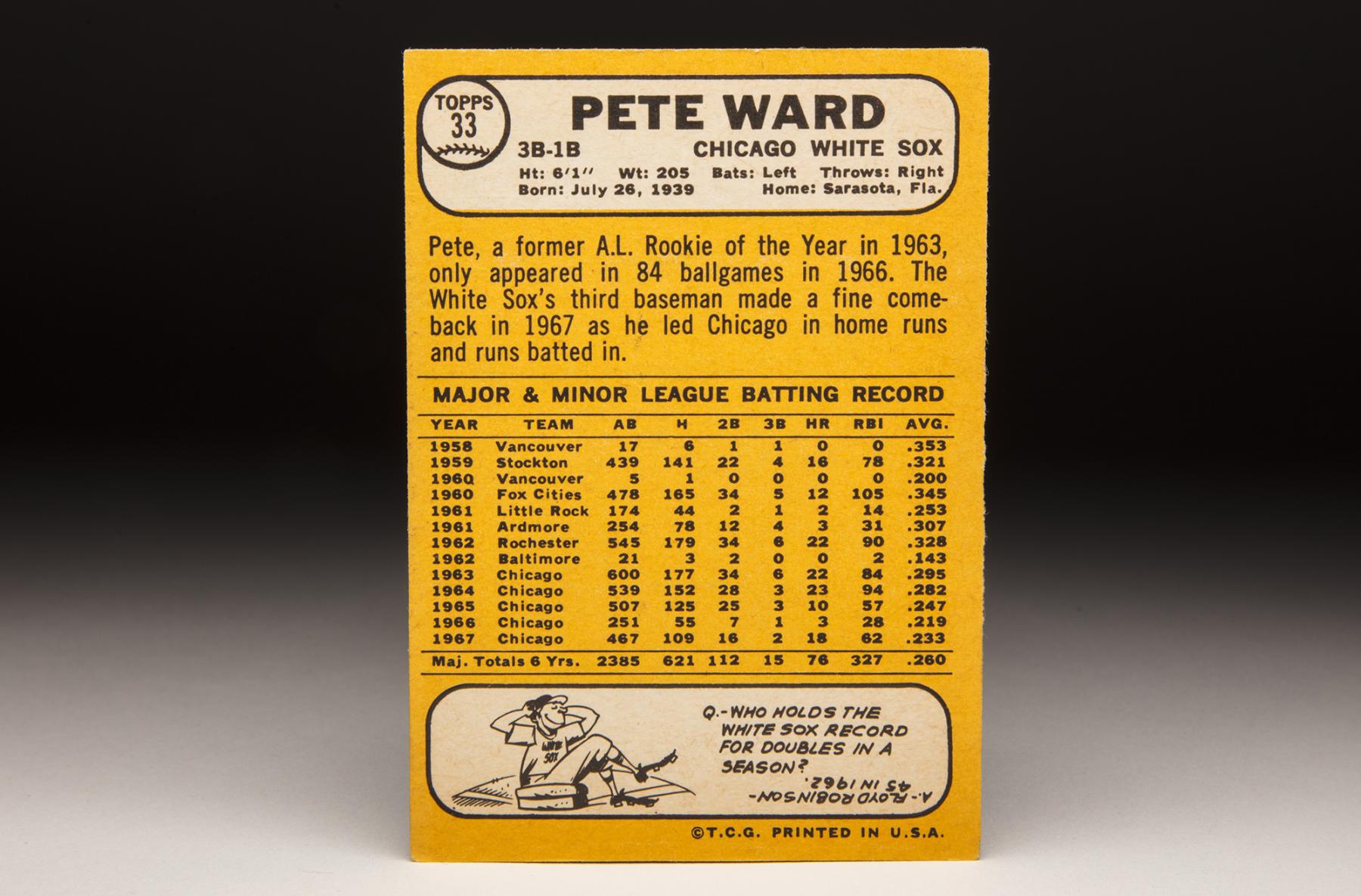

Ward’s professional career began in 1958, when he agreed to his first contract with the Baltimore Orioles. Signing late, Ward was assigned to Triple-A Vancouver of the Pacific Coast League. Even though he was only 20, he batted .353 in 11 games. He also raised some eyebrows with his unusual hitting style. Employing a grip straight out of the 19th century, Ward kept his hands about a half-inch apart as he held the bat. The gap would keep growing, to the point that he held his hands three to four inches apart.

Ward seemed capable of playing fulltime Triple-A in 1959, but the Orioles decided to assign him to their lower level Class C affiliate in Stockton. Predictably, Ward battered California League pitching to the tune of a .321 batting average. In 1960, he moved up to Class B, and then on to Double-A in 1961, when the Orioles switched him to the outfield. That’s also when Ward decided to change his batting grip. Believing that the split-hand grip was hurting his power, Ward brought his hands together in a more conventional style preferred by players of the era. He also spent most of his time living in a tent, which he shared with a teammate, located about a hundred yards from the ballpark.

Regardless of his living conditions, or the grip that he used at the plate, Ward continued to hit. Then came a call to Triple-A Rochester in 1962; there he batted .328 with 22 home runs and 76 walks. Clearly, Ward was ready for the big leagues.

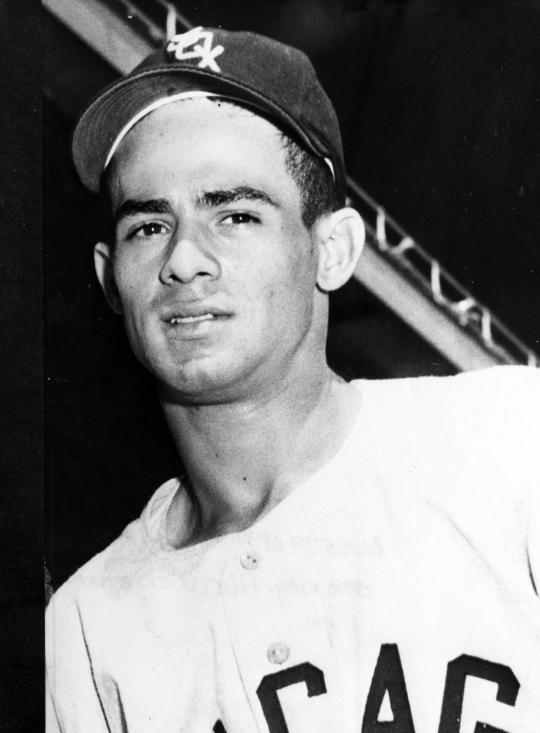

That chance would come late in 1962. With Brooks Robinson entrenched at third base, the Orioles used Ward in the outfield corners. He came to bat 21 times, picking up only three hits.

The Orioles needed help in the outfield, but they had doubts about Ward’s ability to handle either left field or right field. In the meantime, the O’s hoped to upgrade their middle infield. That winter, the Orioles engaged the White Sox in trade talks for All-Star shortstop Luis Aparicio and infielder/outfielder Al Smith. The price tag was hefty: reliever Hoyt Wilhelm, infielder Ron Hansen, outfielder Dave Nicholson, and Baltimore’s prized prospect, Ward.

Ward proved a perfect fit for the White Sox, where he replaced replaced the aging Smith at third base. At first, though, Ward did not make a good impression. When Sox manager Al Lopez first took note of Ward’s batting stance, he cried out, “Oh no,” according to an article in Sport magazine. “Is this what we gave up Aparicio for?” As Ward stepped into the batter’s box, he typically set himself into a deep crouch, while keeping his feet spread unusually apart.

“He does it all wrong,” White Sox coach Charlie Metro told Sport. “He hits off the front foot, and off the back foot. He’s never ready. He takes a terrible-looking cut.” But then something in Ward’s hitting process clicked in. “Until the bat makes contact,” Metro added, “and then that ball jumps.”

Indeed it did. As the Sox’ regular third baseman, Ward batted .295 with 22 home runs. He also drew 52 walks. With his patient approach, Ward reached base 35 percent of the time.

Ward also played the game hard. The antithesis of a showboat, Ward ran out every ball and loved to get his uniform dirty. As sportswriter Roy McHugh described, Ward would have fit in well with the “Gashouse Gang” St. Louis Cardinals of the 1930s. “Untidiness goes with his style,” wrote McHugh, “for Pete has come as a latter-day Gas House Gangster himself, a gabby, disheveled, hilariously absent-minded, impish anachronism who can hit.”

Ward’s hitting helped the White Sox win 94 games in 1963 and finish a strong second in the American League pennant race. Ward’s only flaw was the occasional defensive lapse; he sometimes struggled to make the routine play. But other than, Ward excelled. Narrowly missing out on AL Rookie of the Year honors, He finished second to teammate and close friend Gary Peters. (Ward did win the AL rookie nod from the Sporting News, however.) Ward also did well in the MVP voting; he finished ninth in the balloting, putting him in top 10 company with future Hall of Famers Al Kaline, Whitey Ford, Harmon Killebrew and Carl Yastrzemski.

While many rookies struggle in their second season – part of the dreaded sophomore jinx – Ward eluded any such problems. In 1964, he put up offensive numbers nearly identical to his rookie season. His batting average dropped a few points, but he increased his walks and his RBI totals, and again received MVP consideration. Ward finished sixth in the balloting in a year that saw his former teammate, Brooks Robinson, take home the award.

With two quality seasons in the book and Ward still only 27, the White Sox had every reason to believe that they solidified third base for years to come. Ward attended Spring Training in 1965 without incident, but shortly after the regular season opened, he became involved in a car accident. Riding as a passenger in a car that was rear-ended by another vehicle, Ward suffered a case of whiplash. At first, Ward felt fine, but a night of sleep left him feeling out of sorts.

“The day after the accident I woke up with a stiff neck,” Ward told Sports Illustrated. “I was never comfortable from that point on.”

Bothered by a sore neck and upper back, Ward slumped to a .247 batting average in 1965. His power fell off precipitously, as he finished the year with only 10 home runs.

In spite of his season-long struggles, Ward was scheduled to appear on the cover of the June 7 edition of Sports Illustrated. Just before the issue went to publication, Muhammad Ali scored a quick knockout against Sonny Liston. The editors at Sports Illustrated decided to change the cover story from baseball to boxing, going with Ali’s win and spotlighting what would become an iconic photo of Ali standing over Liston’s fallen body. Ward never did make the cover of the weekly publication.

The Sports Illustrated decision left Ward disappointed, but it was the neck injury from the car accident that caused the real long-term damage to his career. After his falloff in 1965, Ward hit so poorly in 1966 that he lost the third base job to Don Buford and became a utility man, filling in at third, first, and the outfield corners. Appearing in only 84 games, Ward batted .218 with three home runs.

The following summer, Ward made a comeback. He returned to the starting lineup, this time in left field, and hit 18 home runs. But he also struck out 109 times, batted only .233, and saw his slugging percentage fall below .400. Clearly, he was not the player he had once been in 1963 and ’64.

The 1968 season brought more of the same, including a career-low batting average of .216. By 1969, Ward was back to playing the utility man. In 105 games, he hit only six home runs.

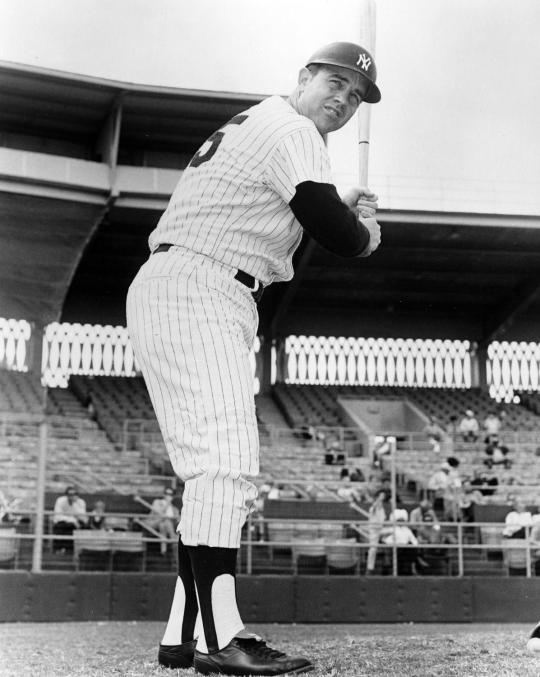

Ward was also on the wrong side of 30. Realizing that he would never recapture his early career glory, the White Sox traded Ward that winter, sending him to the New York Yankees for pitching prospect Mickey Scott.

With his left-handed bat and power potential, the Yankees hoped that Ward might be rejuvenated playing his home games at Yankee Stadium. Even with the short porch in right field, Ward hit only one home run on the season, and that came on the road. He did bat .260 in 66 games as a utility player, but the complete lack of power proved disappointing for the Yankees.

Still, the Yankees brought Ward back for Spring Training in 1971. On March 31, just before Opening Day, the Yankees opted to release Ward. At 33 years of age, Ward’s playing career had come to an end.

Ward, however, would soon rejoin the Yankees’ organization. In 1972, he began a six-year stint as a minor league manager in the Yankee system, culminating in an Eastern League championship. In 1978, the Atlanta Braves hired Ward for their major league coaching staff. Two years later, he returned to the minor league ranks, at first with the White Sox and then with the Pittsburgh Pirates.

In the 1980s, Ward left baseball entirely to join the travel industry, where he successfully ran his own company for years. He passed away on March 17, 2022.

While Ward’s playing career saw its share of setbacks – from a career-altering injury to the last-minute elimination from the cover of Sports Illustrated – he harbored no regrets.

He might not be a household name anymore, but there are still plenty of baseball fans who remember that “Aw shucks” smile and that toothy grin.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame