- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1969 & 1977 Topps Chuck Hartenstein

#CardCorner: 1969 & 1977 Topps Chuck Hartenstein

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

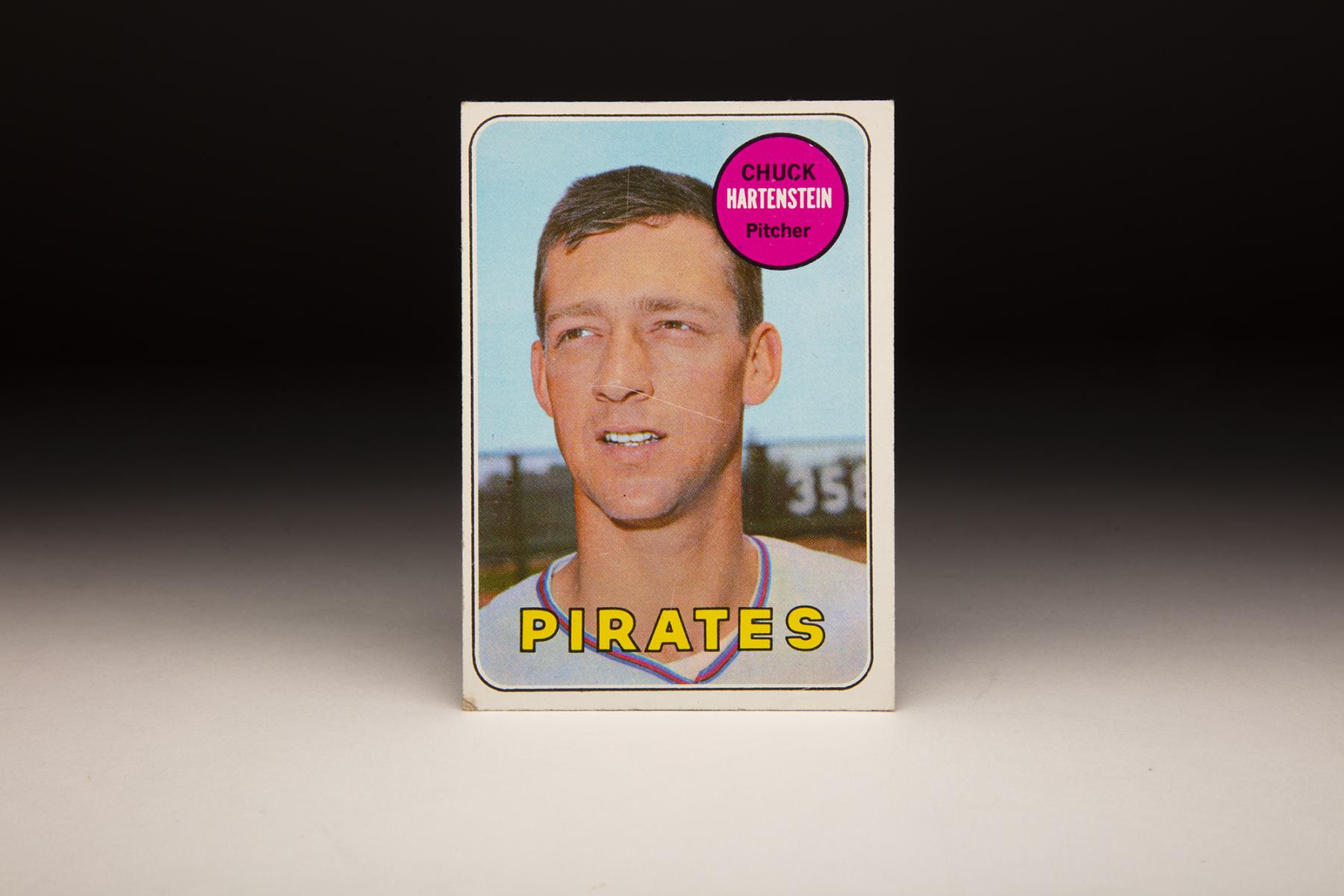

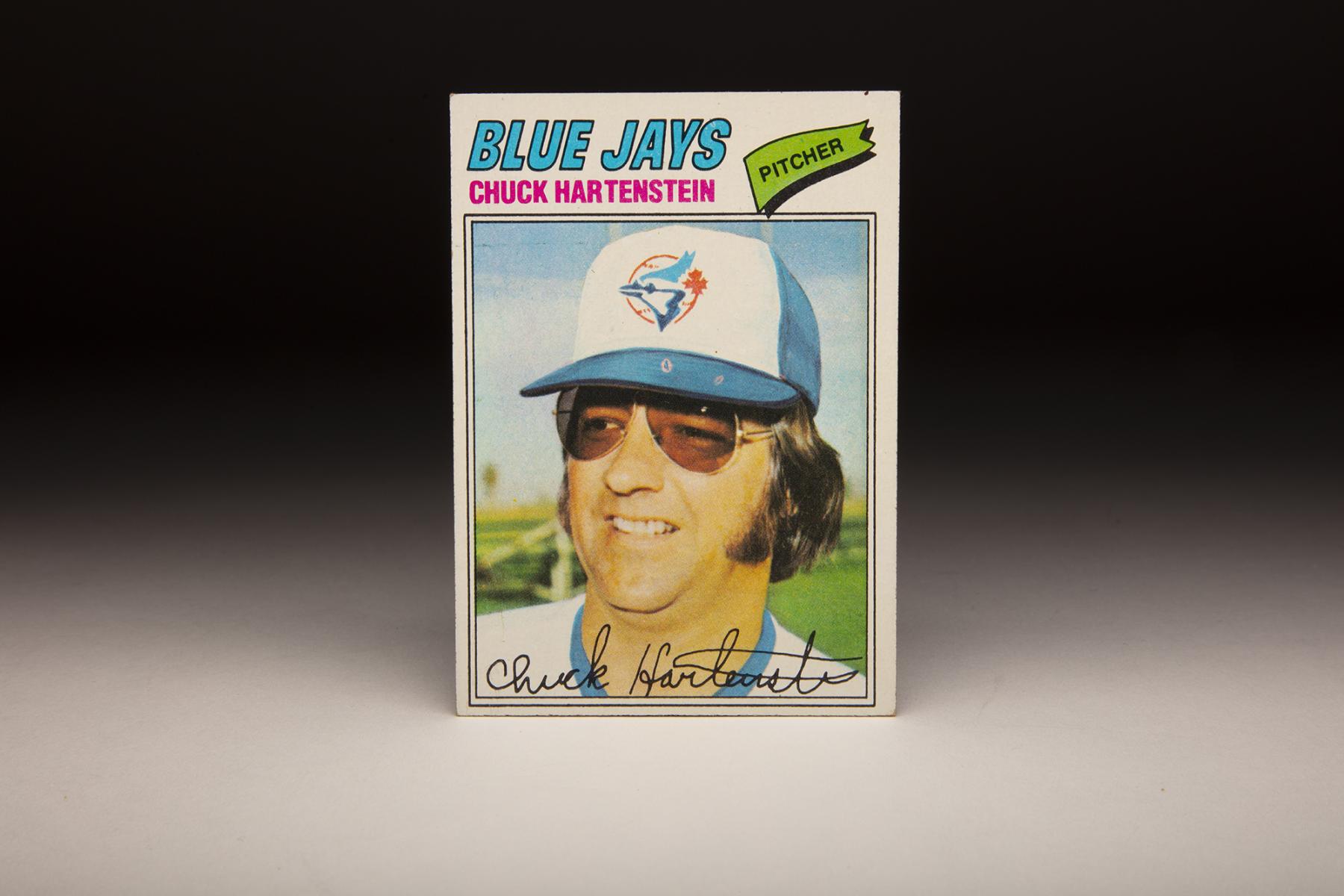

Could the players shown on these two cards really be the same man?

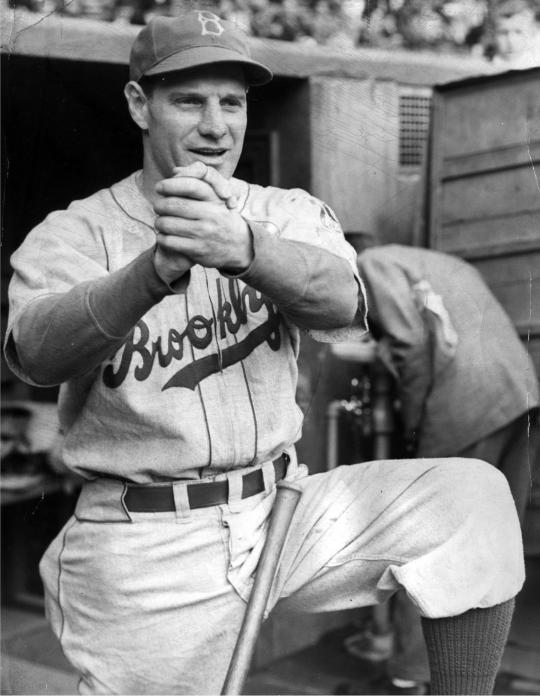

The first card, part of Topps’ 1969 set, shows a player who appears to be extremely thin, with a long neck, and a clean and tidy haircut that was consistent with baseball fashion of the day.

Official Hall of Fame Apparel

Proceeds from online store purchases help support our mission to preserve baseball history. Thank you!

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

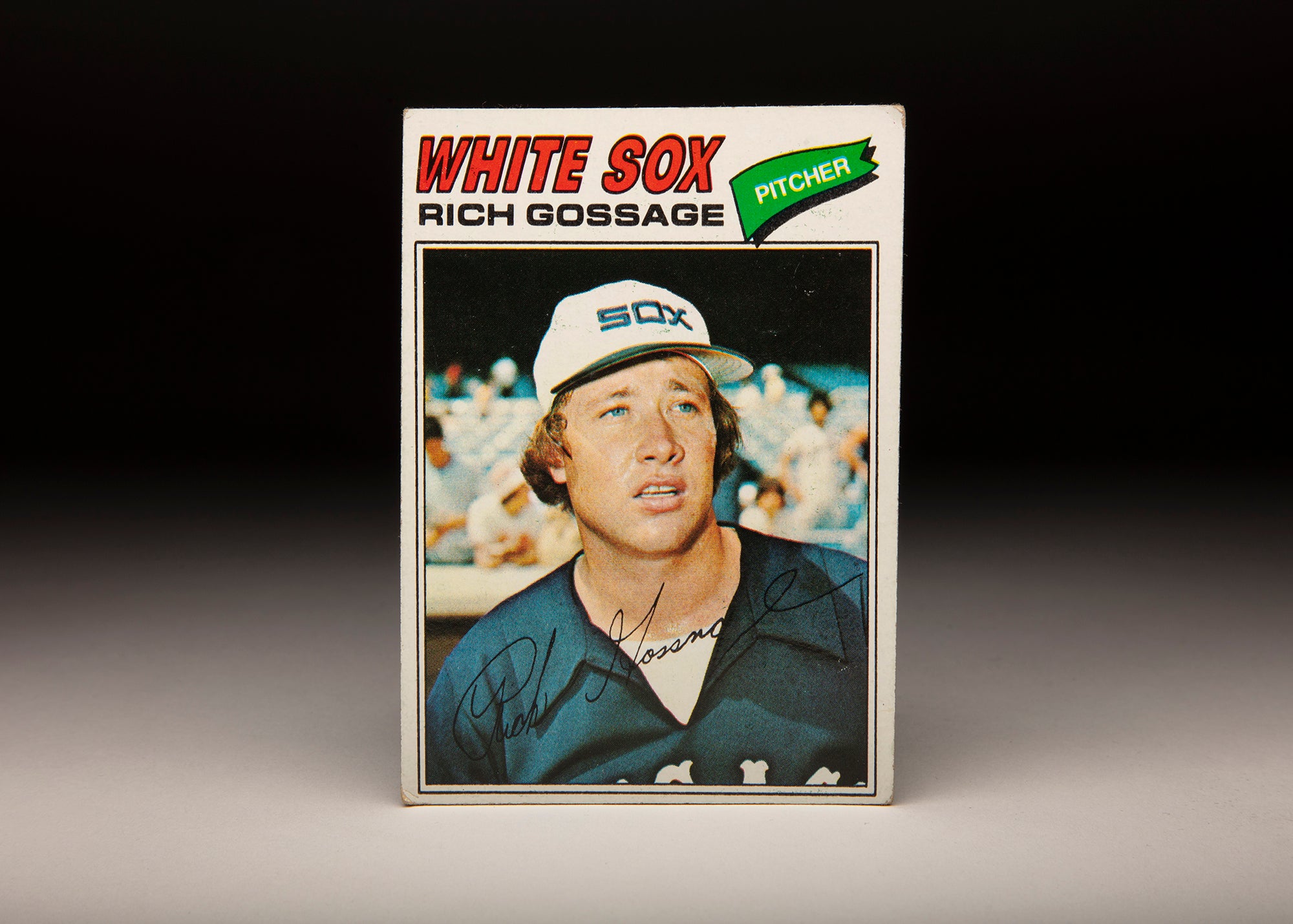

The second card, which came out eight years later as part of the 1977 set, gives us a player who is far heavier, perhaps as much as 40 pounds so. He is equipped with a double chin, heavy sideburns, and long flopping hair that cover his ears, along with a large pair of aviator sunglasses.

Are these really two photographs of the same man, albeit separated by eight years?

Well, yes. Yes, they are. There is no mistaken identity here. There were not two different Chuck Hartensteins who pitched in the major leagues in the 1960s and 70s. That is Chuck Hartenstein on the 1969 Topps card, and that is the same Chuck Hartenstein on the 1977 card. Different looks, but the same person.

The cards serve as evidence that a lot can change in the span of eight years. They also give us a glimpse into a story of a pitcher whose major league career had seemingly ended in 1970, only to find new life, however briefly, during the expansion season of 1977.

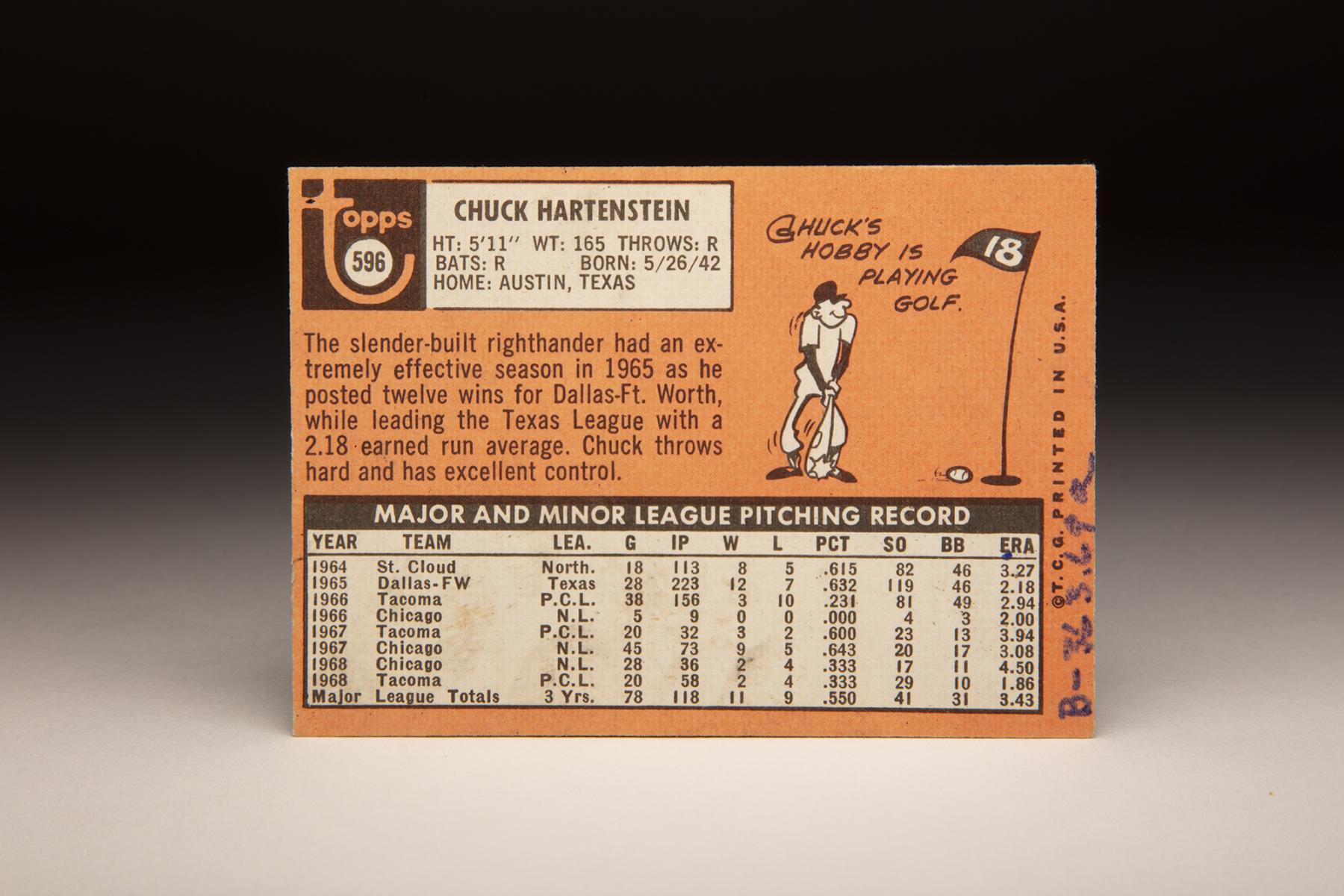

In actuality, Hartenstein also appeared on a card in the 1970 Topps set, but it doesn’t give us a particularly good view of the right-handed relief pitcher, nor does it quite give us the contrast that we see between the 1969 and ’77 cards. After appearing on the Topps cards in ’69 and ’70, Hartenstein did not appear in any of the next six Topps sets: 1971, ’72, ’73, ’74, ’75 or ’76. And that was for good reason. Hartenstein did not pitch in the major leagues during any of those seasons.

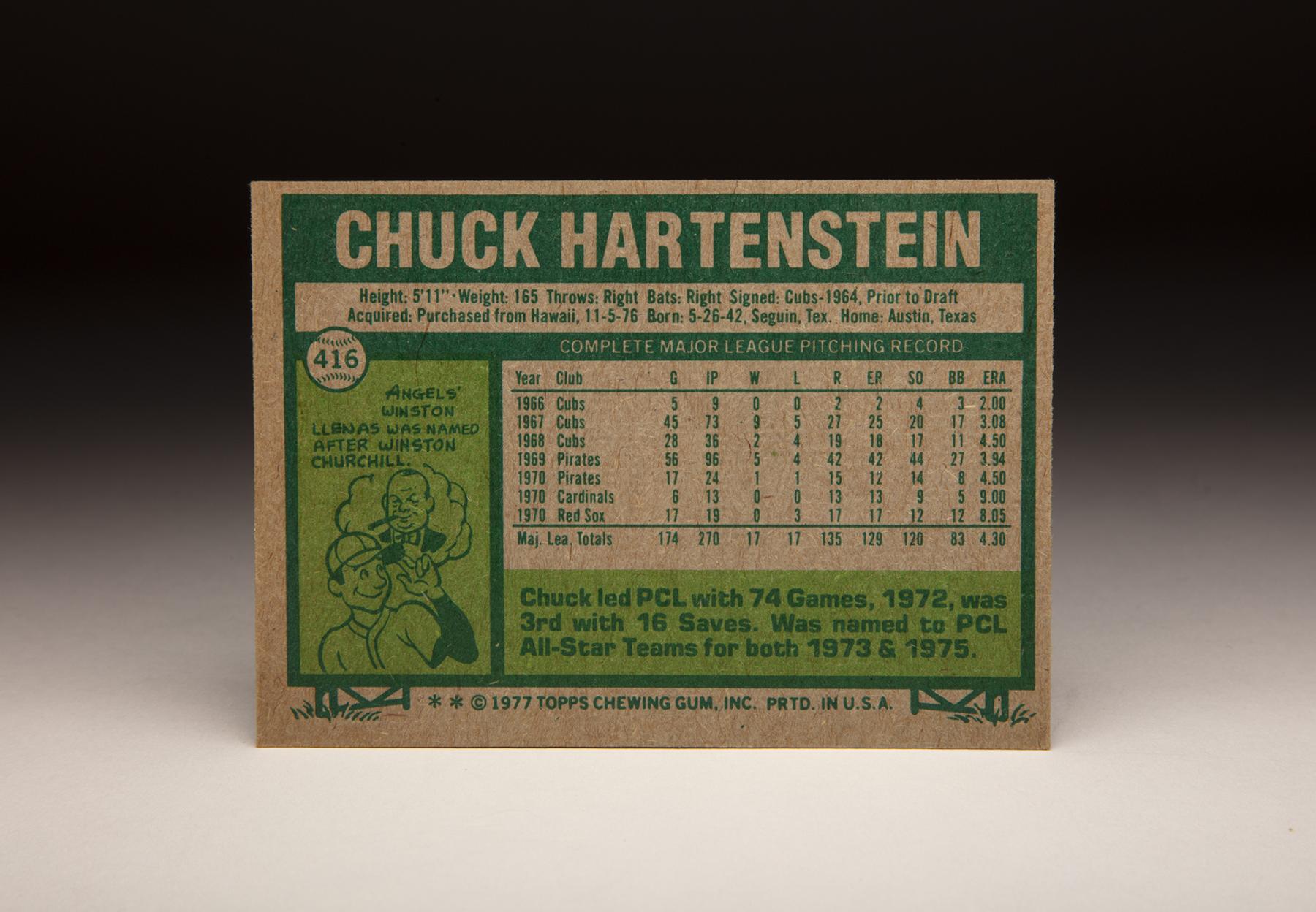

Much to his credit, Hartenstein did not give up his quest to continue his career. He toiled in the minor leagues for almost all of that interim period, long enough to maintain a foothold in the game until the expansion Toronto Blue Jays came calling in 1977. While that follow-up pitching tenure did not last very long, it did allow Hartenstein to pursue a second career as a coach.

Hartenstein’s first career as a pitcher began 13 years earlier. The Chicago Cubs signed him as an amateur free agent in 1964, four years after he turned down a bonus from the Detroit Tigers.

“I couldn’t accept it,” Hartenstein told writer James Enright, “since I promised [Bibb] Falk that I would fulfill the four-year scholarship which he offered me (at the University of Texas).” With his commitment to Texas fulfilled, Hartenstein felt free to sign with the Cubs, who assigned him to St. Cloud of the Class A Northern League. There he racked up 15 starts, pitched 113 innings, and recorded an ERA of 3.27. In 1965, the Cubs promoted him to Double-A Dallas/Ft. Worth of the Texas League, where he pitched even better. He won 12 of 19 decisions and posted an ERA of 2.66.

Even though Hartenstein was all of 5-foot-11 and weighed only 150 pounds, he impressed the Cubs so much that they brought him up to the big leagues in September. He appeared in one game – as a pinch-runner. Unfortunately, Hartenstein had injured his arm late in the ’65 minor league season, preventing him from making his first pitching appearance for the Cubs.

In the spring of ’66, Hartenstein reported to Spring Training on time, but unable to crack 60 miles an hour with his fastball. In an effort to diagnose the problem, he asked his wife to shoot some home movies of him while pitching; the film showed Hartenstein that his mechanics were out of synch. Correcting the problem, he began to throw harder and stretched out the tendons in his arm, which had become restricted. Now throwing freely and with ease, Hartenstein recovered to pitch on Opening Day for Tacoma, the Cubs’ Triple-A affiliate in the Pacific Coast League.

Hartenstein won only three out of 13 decisions for Tacoma, but that was mostly a product of bad luck and lack of run support. With an ERA of 2.94, Hartenstein was roughly a run better than the league average in the hitter-friendly PCL.

In September, the Cubs rewarded Hartenstein with his second promotion to the big leagues, this time with a chance to pitch in an actual game. Using him in long relief, the Cubs saw him scatter eight hits in nine innings, while putting up an ERA of 1.93 in five games.

After a brief return to Tacoma in April and May of 1967, the Cubs brought Hartenstein back to Chicago in June. They used him out of the bullpen the remainder of the season, but not just in the middle innings. Pitching frequently in the eighth and ninth innings, Hartenstein notched 11 saves to lead the Cubs’ staff. Employing a sidearm motion and a sinkerball that had been taught to him by Cubs pitching guru Fred Martin, Hartenstein posted an ERA of 3.08 and appeared to be well on his way to emerging as a key member of Leo Durocher’s bullpen.

“Nothing seems to disturb him,” Durocher told famed writer Jerome Holtzman, corresponding for the Sporting News. “He is really something.”

Hartenstein also picked up a nickname that summer. Writers and teammates began to call the quiet, polite right-hander “Twiggy,” an homage to his exceedingly lean appearance. (It was also a reference to British model Lesley Hornby, another rail-thing figure known universally as Twiggy.)

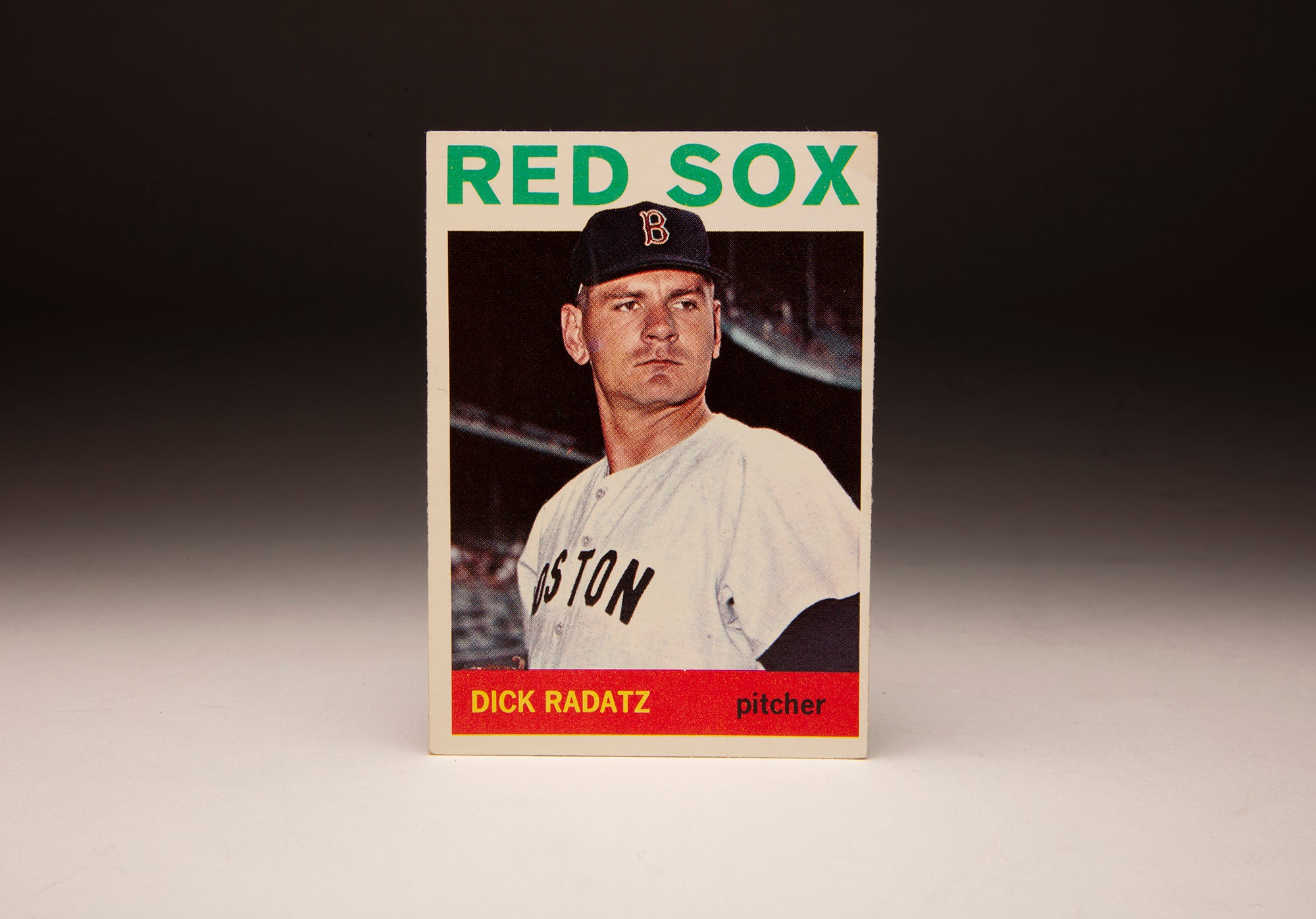

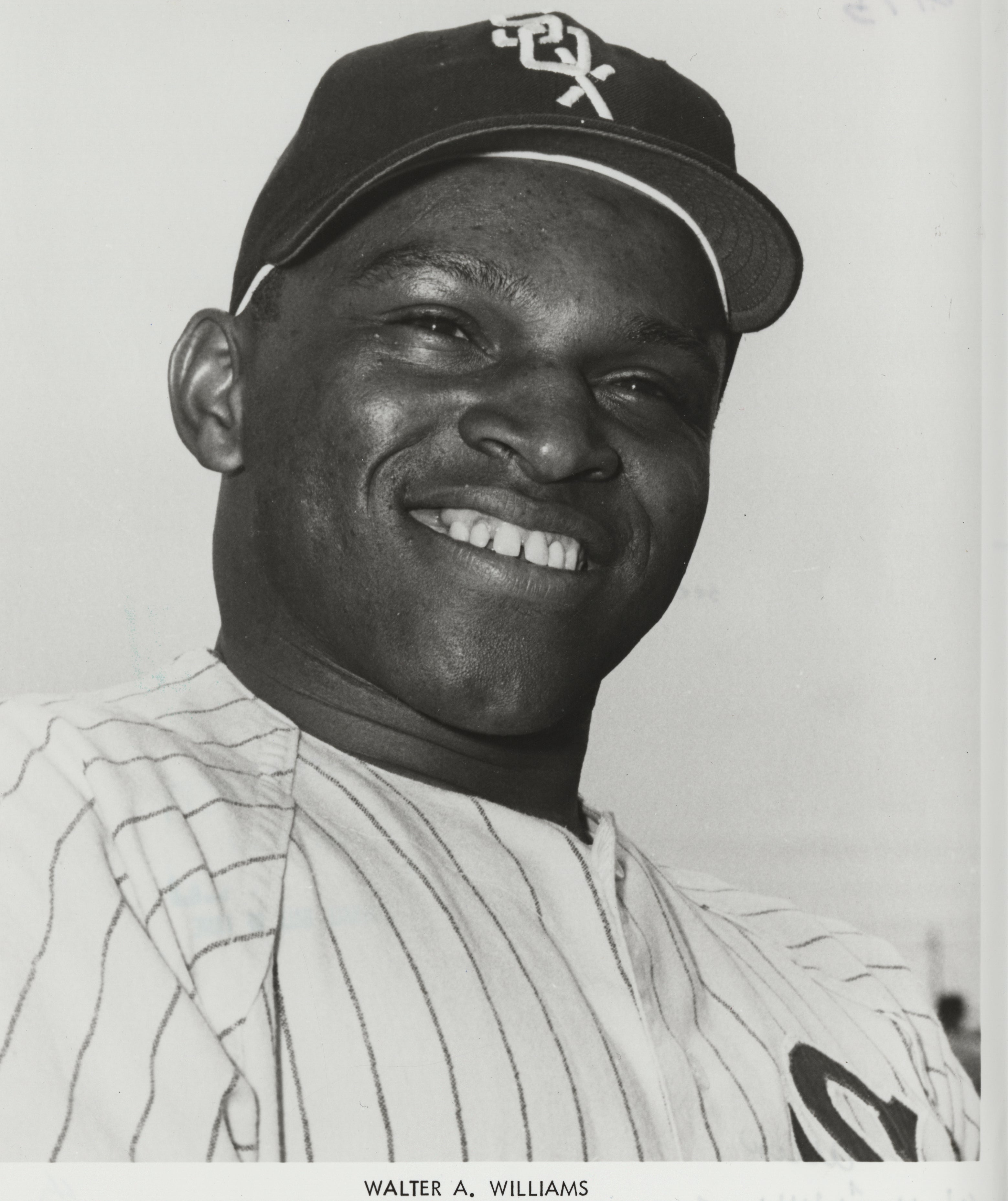

According to Holtzman, the nickname had been given to Hartenstein by teammate Dick Radatz, the man known as “The Monster,” who looked as different from Hartenstein as Lou Costello did from Bud Abbott. But in actuality, the nickname came from another Cub, Hall of Famer Billy Williams, who lockered next to Hartenstein. When Williams saw a group of writers huddled around Hartenstein, he yelled out to his teammate, “Twiggy!” The writers heard the moniker and began to use it in their game stories.

Hartenstein embraced the nickname. “I was happy to get the recognition. Most ballplayers look alike,” he told sportswriter Bill Christine of the Pittsburgh Press. “It gave me some identity.”

The 1968 season would turn out to be the Year of the Pitcher, but it was not the year of Hartenstein. Surprisingly, the Cubs demoted him to Tacoma just before Opening Day.

Upon his return to Chicago, he was unable to regain his role as the Cubs’ relief ace and saw his ERA balloon to 4.54.

Throughout the season, Hartenstein struggled in his relationship with Durocher. The two men differed in how the relief pitcher should be used. At one point, Hartenstein asked Cubs general manager John Holland to trade him. That winter, Holland obliged, sending Hartenstein to the Pittsburgh Pirates for reserve outfielder Manny Jimenez.

With no updated photographs of Hartenstein wearing the black and gold of the Pirates, the Topps Company resorted to an old file photo of him wearing a Cubs jersey – and no cap. Hartenstein would spend the entire season 1969 season in Pittsburgh, appearing in 56 games with an ERA of 3.95.

It was a decent season for Hartenstein, but the Pirates wanted better from him in 1970. During Spring Training, pitching coach Don Osborn approached Hartenstein about ditching his sidearm motion and adopting an overhand pitching delivery. Hartenstein tried the new style, but struggled, both in the spring and during the regular season. By June, the Pirates had seen enough. They waived Hartenstein, who soon found work with the St. Louis Cardinals.

To put it bluntly, Hartenstein flopped in St. Louis. He appeared in six games, allowing 13 earned runs in 13 innings. By late July, the Cardinals gave up on the veteran righty, sending him to the Boston Red Sox in a conditional trade.

Hartenstein fared no better in Boston than he had in St. Louis. In September, the Red Sox demoted him to Triple-A Louisville, even though the Triple-A season had come to an end. On New Year’s Eve, the Red Sox shed his contract, sending him to the Chicago White Sox in a cash transaction.

Hartenstein would never pitch for the White Sox. In 1971, he toiled for Chicago’s Triple-A affiliate, the Tucson Toros. And then in 1972, the players’ strike interrupted the start of the major league season. In order to save money, Sox general manager Roland Hemond cut Hartenstein loose, but he convinced Toros management to bring back Hartenstein on a minor league deal.

Although Hartenstein again spent the entire summer in the minor leagues, he enjoyed playing for manager Larry Sherry and pitched some of the best ball of his career, recording an ERA of 3.00 with 16 saves in 114 innings. Hartenstein praised Sherry for using him properly, allowing him to thrive in the minor league setting.

Just before Spring Training in 1973, the White Sox traded Hartenstein to the San Francisco Giants, who assigned him to Triple-A Phoenix. He would spend the next two seasons pitching in short relief, doing dependable work for managers Jim Davenport and Rocky Bridges.

Hartenstein reported to Spring Training in 1975, only to be given his unconditional release by a Giants team that had no room in its bullpen for an aging reliever. No one could have blamed Hartenstein, now 32 years old, for quitting the game, but he chose to pursue other a job with other teams. In May, he found work with the Triple-A Hawaii Islanders, who had become a haven for former major leaguers. With Honolulu’s warm weather and tantalizing beaches, there were far worse places to play in the minor leagues. For the next two seasons, Hartenstein pitched beautifully out of the Islanders’ bullpen.

By managing to keep himself in circulation, Hartenstein bridged the gap to baseball’s latest round of expansion. Two new teams, the Seattle Mariners and Toronto Blue Jays, were preparing to play their inaugural season in 1977. Scouts from the Blue Jays took notice of Hartenstein at Hawaii. On Nov. 5, the Blue Jays officially purchased his contract from Hawaii and invited him to the team’s first Spring Training camp.

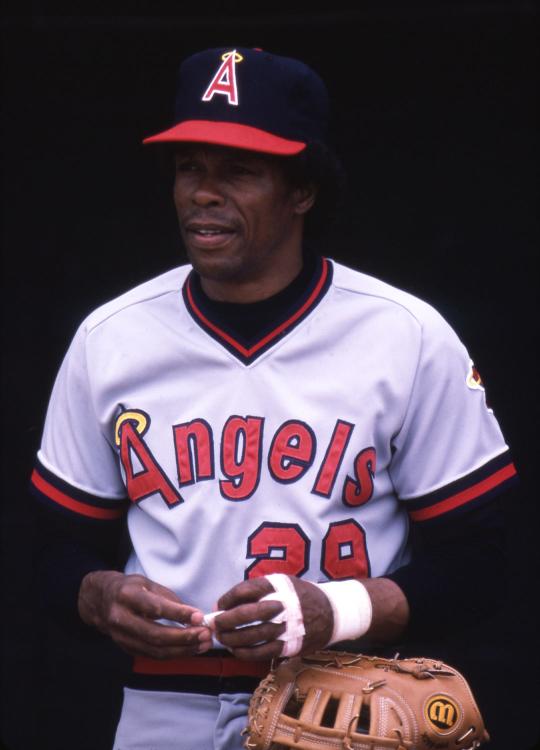

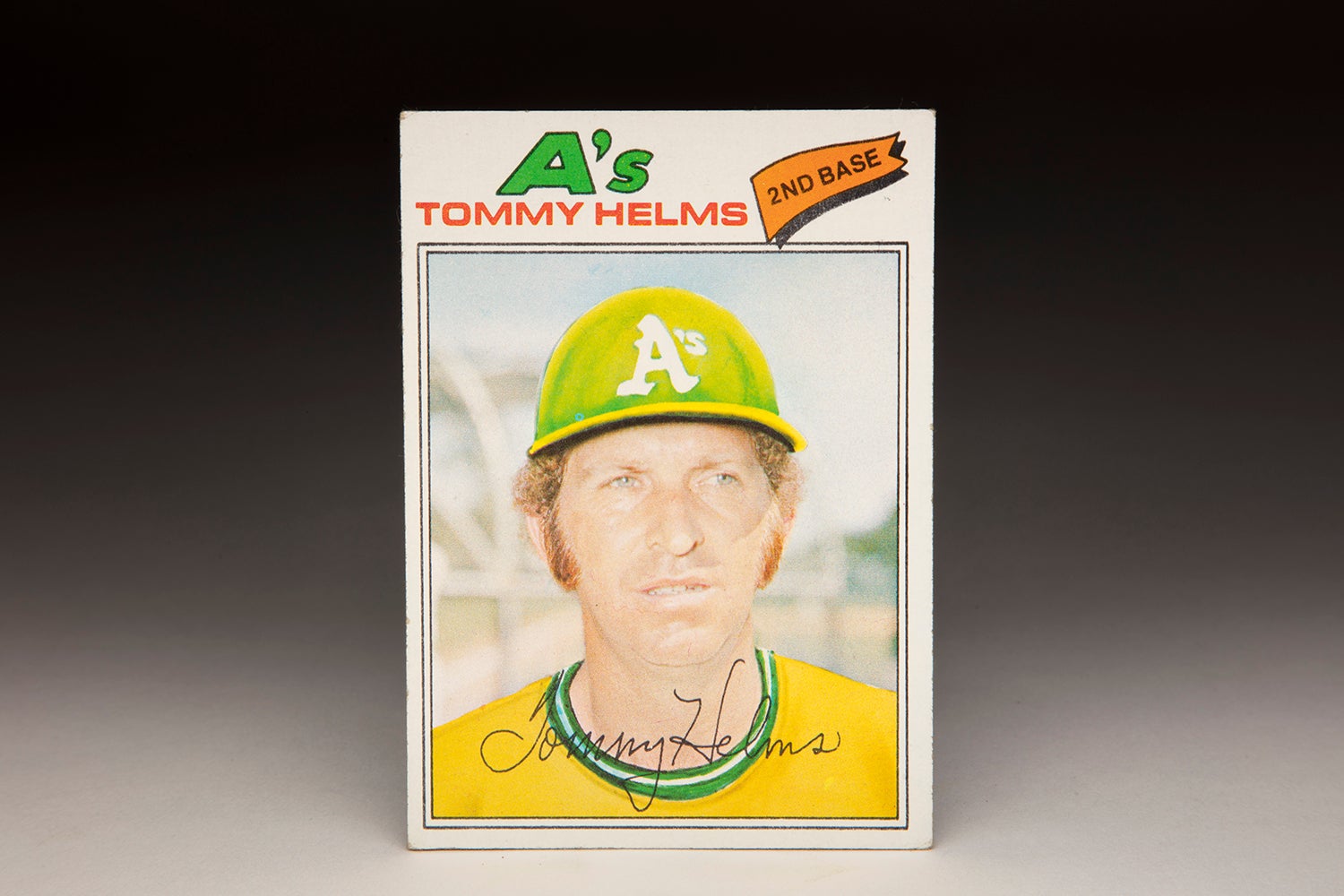

With the news that Hartenstein had been added to the Jays’ 40-man roster, the Topps Company responded by issuing a card for him as part of its 1977 set. Sure enough, Hartenstein made Toronto’s Opening Day roster, appearing in uniform for the team’s first game at Exhibition Stadium. He made seven relief appearances in April and May before being hit in the pitching hand by a Rod Carew line drive. The comebacker broke Hartenstein’s right thumb, keeping him out of action for the next month and a half.

As he recovered, Hartenstein did some work as an advance scout for the expansion Jays. He then returned to the mound in July, making six more appearances for the franchise. Though he did not pitch well, he garnered enough service time to qualify for a full major league pension.

On Sept. 2, the Blue Jays officially announced that Hartenstein had become their minor league pitching instructor. He remained in that position through the end of 1978, when the Cleveland Indians hired him as their major league pitching coach. A managerial change in Cleveland ended that job one year later, but Hartenstein found work in the minor leagues for much of the 1980s before becoming the Milwaukee Brewers pitching coach in 1987. Then came a series of scouting opportunities with several organizations before he decided to retire from the game in 1995.

By the time he left the game, Hartenstein had put in over 30 years. It was a career that could have ended much sooner, if not for his perseverance and his determination. By extending his career in the minor leagues, he created options for the future, allowing himself one more taste of the major leagues, and then long tenures as a coach and as a scout.

Chuck Hartenstein could have given up, but hard work led to a better path.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame