- Home

- Our Stories

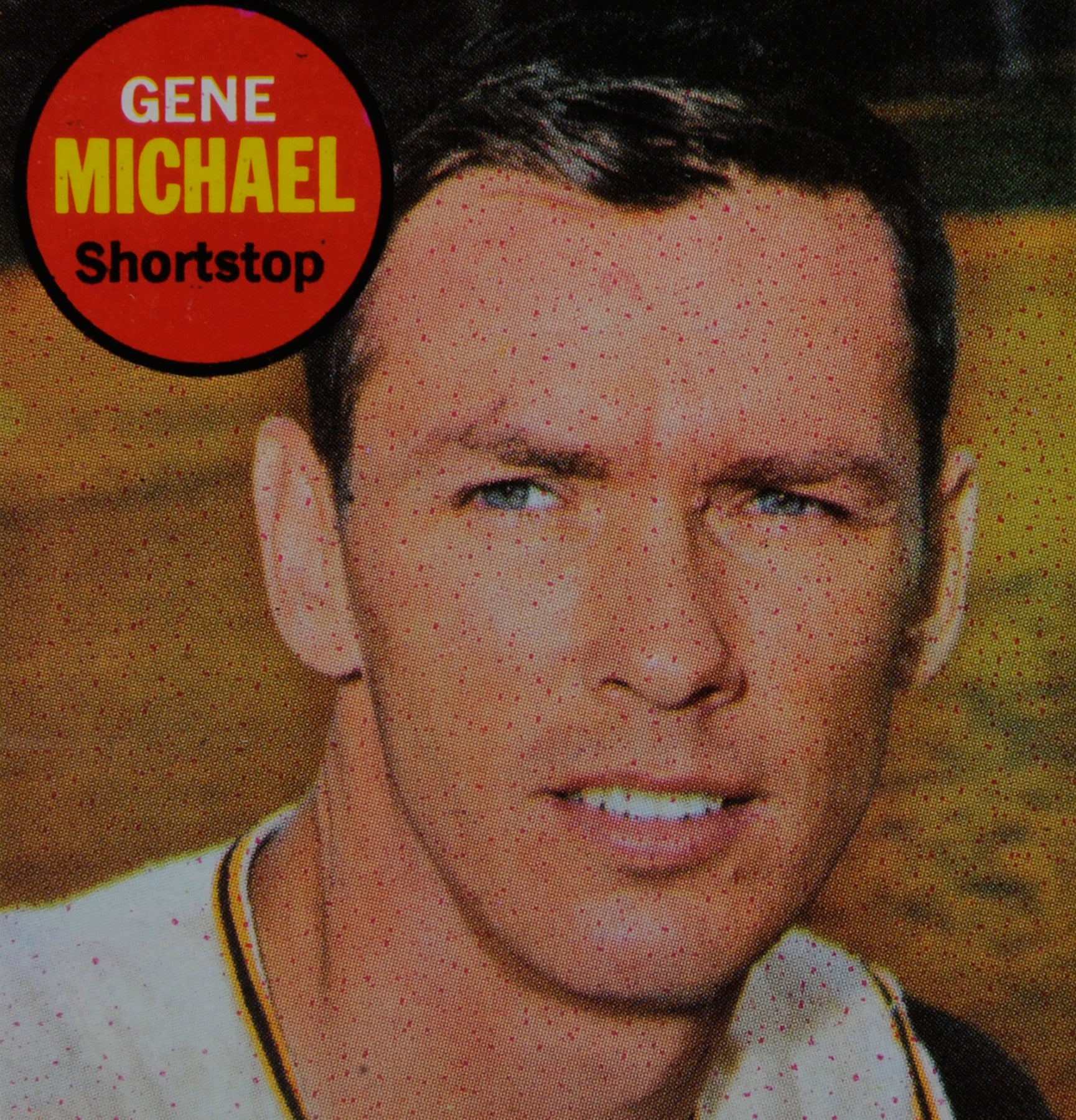

- #CardCorner: 1972 Topps Bob Robertson

#CardCorner: 1972 Topps Bob Robertson

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

During the early stages of this year’s postseason, Jose Altuve of the world champion Houston Astros did something that has been rarely done in either the playoffs or the World Series. He hit three home runs in a single game, scoring the unusual hat trick in Game 1 of the Division Series against the Boston Red Sox.

Later on, Enrique Hernandez clubbed three home runs in a Championship Series game for the Los Angeles Dodgers. A few other notables have enjoyed a three-homer game during the postseason, including Hall of Famers Babe Ruth (in both the 1926 and ‘28 World Series), Reggie Jackson (the 1977 World Series), and George Brett (the 1978 ALCS). The names of some of the other players to accomplish this might not be as recognizable. In 2002, Adam Kennedy of the Los Angeles Angels hit three home runs in an ALCS game; that was rather remarkable, since Kennedy hit all of 80 home runs for his career and was never regarded as a power hitter.

That leaves us with another intriguing name: Bob Robertson. In the 1971 National League Championship Series, Robertson slugged three home runs in Game 2 for the Pittsburgh Pirates. While the name might not be recognizable to many fans today, the story was different in 1971; if you followed the game in the early 1970s, you would not have been all that surprised to see Robertson go deep three times. He had extraordinary power at the height of his career, enough to garner comparisons to the great Ralph Kiner, who had preceded him in Pittsburgh several decades earlier. Others called him a younger version of Harmon Killebrew.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

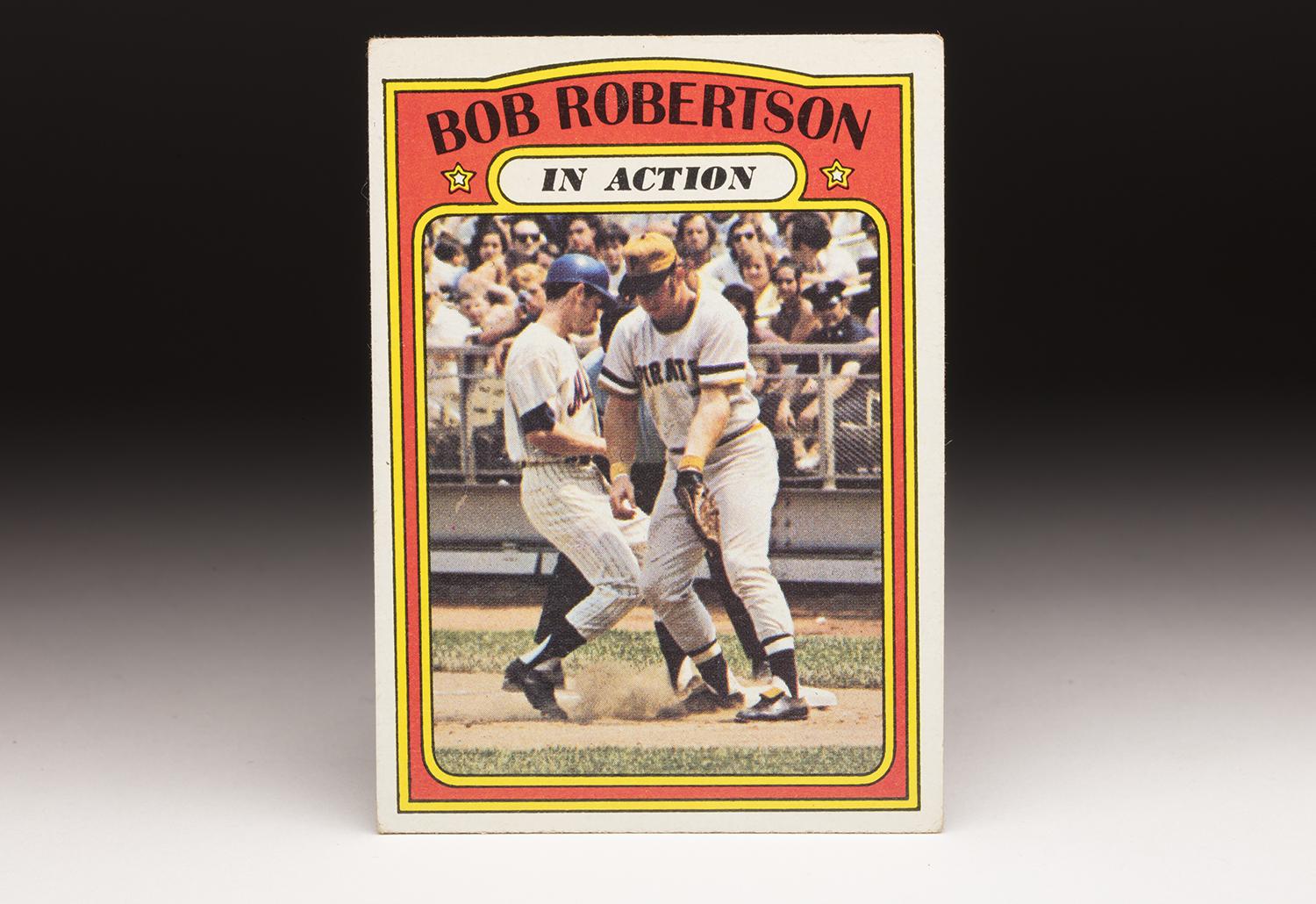

A gander at Robertson’s 1972 Topps “In Action” card reinforces the notion that he had substantial power. Although the action shot does not show him with a bat in his hands, and instead has him taking a pickoff throw at first base during a 1971 game at Shea Stadium, it does give us a glimpse at his muscularity.

Let’s juxtapose the frame of Robertson and his Popeye-like figure against the more ordinary build of New York Mets shortstop Bud Harrelson. The photograph reminds me of the old television show, Land of the Giants, which was cancelled only two years before the card came out. It was a show about astronauts who had landed on a planet that they originally believed to be Earth, only to realize that it was an alien planet where the inhabitants possessed the average build of a New York City skyscraper. On the card, Robertson takes on the role of the giant, while Harrelson looks more like the ordinary human.

In some ways, I’m exaggerating the size of Robertson. He wasn’t that much bigger than Harrelson, but he did outweigh him by about 45 pounds. More than anything, it is the size of Robertson’s forearms that really stand out. In the years before weightlifting became common practice for big league players, Robertson looked like a guy who did free-lifting curls by the dozen. In an era when most ballplayers were similar in size to the general population, Robertson stood out as a Bunyanesque character, someone whose arms were thick enough and strong enough to pick up an opposing baserunner, lift him off the ground, and carry him into the first base dugout.

Not only does Robertson look like a block of granite on this Topps card, but his glove also takes on a supersized quality. It seems about as large as a cesta in the sport of Jai alai, capable of holding multiple baseballs at once. I imagine that when Robertson slapped a tag on a baserunner with that frying pan-sized mitt, it felt less like a tickle and more like a lead apron being dropped onto bare skin.

Robertson’s career reached its peak with his three-homer game in 1971, but his journey to Pittsburgh began several years earlier in 1964. That happened to be the final year in which amateur players could sign with any team of their choosing, rather than be subject to the MLB Draft. The red-haired Robertson signed on with the Pirates’ organization, which assigned him to the distance reaches of the Appalachian League, a rookie league at the time.

Playing third base for a team in Salem, Va., Robertson immediately made an impression. He hit 13 home runs in only 70 games, batted .302, and posted an OPS of .884.

From 1964 to 1966, Robertson moved up quickly through the Pirates’ system, jumping from Rookie Ball to Class A and then to Double-A. His first bit of physical adversity came in the middle of the 1966 season, when a pitch struck him on the wrist, chipping one of the bones. Pirates’ doctors recommended that surgery not be performed, feeling that an operation would not help. So Robertson played with a kind of arthritic pain in his hand, which affected his hitting in the latter half of 1966 and into 1967.

In spite of the injury, the Pirates moved Robertson up to Triple-A Columbus in 1967. Robertson hit with power, but batted only .256, in part because of his hand injury. Yet, the Pirates still rewarded him with a late-season promotion. Robertson hit only .171 in his 1967 debut, an indication that he wasn’t quite ready, which was certainly understandable given that he was all of 20 years old.

Another physical setback hit Robertson in 1968. Prior to the season, he developed an obstruction in his kidney, a condition that required surgery. The situation was so serious that Robertson missed all of the 1968 season, completely negating what could have been a valuable year of development.

For some players, such a development could have stalled a career, but Robertson worked hard to return to action in 1969. On the basis of a strong Spring Training performance, he made the Pirates’ Opening Day roster. The Pirates put Robby at first base, but a slow start to the season indicated that he needed more minor league time. In the middle of May, he returned to Triple-A Columbus. Now fully healthy, he clubbed 34 home runs and slugged a torrid .589 in 422 at-bats. The Pirates then brought him back for another look in September.

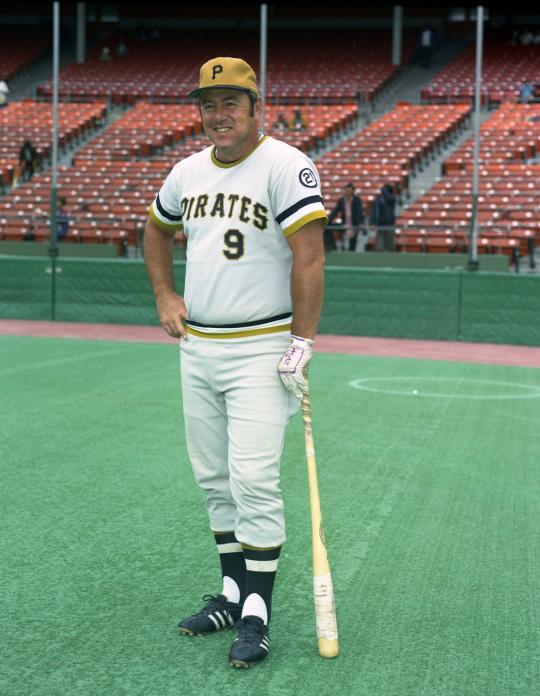

As the Pirates prepared for the 1970 season, they viewed Robertson as an important piece to their infield puzzle. Healthy and ready to hit major league pitching, Robertson split time at first base with Al Oliver to start the season, but became the everyday first baseman by midsummer. He emerged as a force – hitting .287 with 27 home runs in 117 games. Among Pirate players, only Willie Stargell hit more home runs. Playing a huge role in the Bucs winning 89 games and taking the National League East, Robertson earned some back-of-the-ballot support for league MVP.

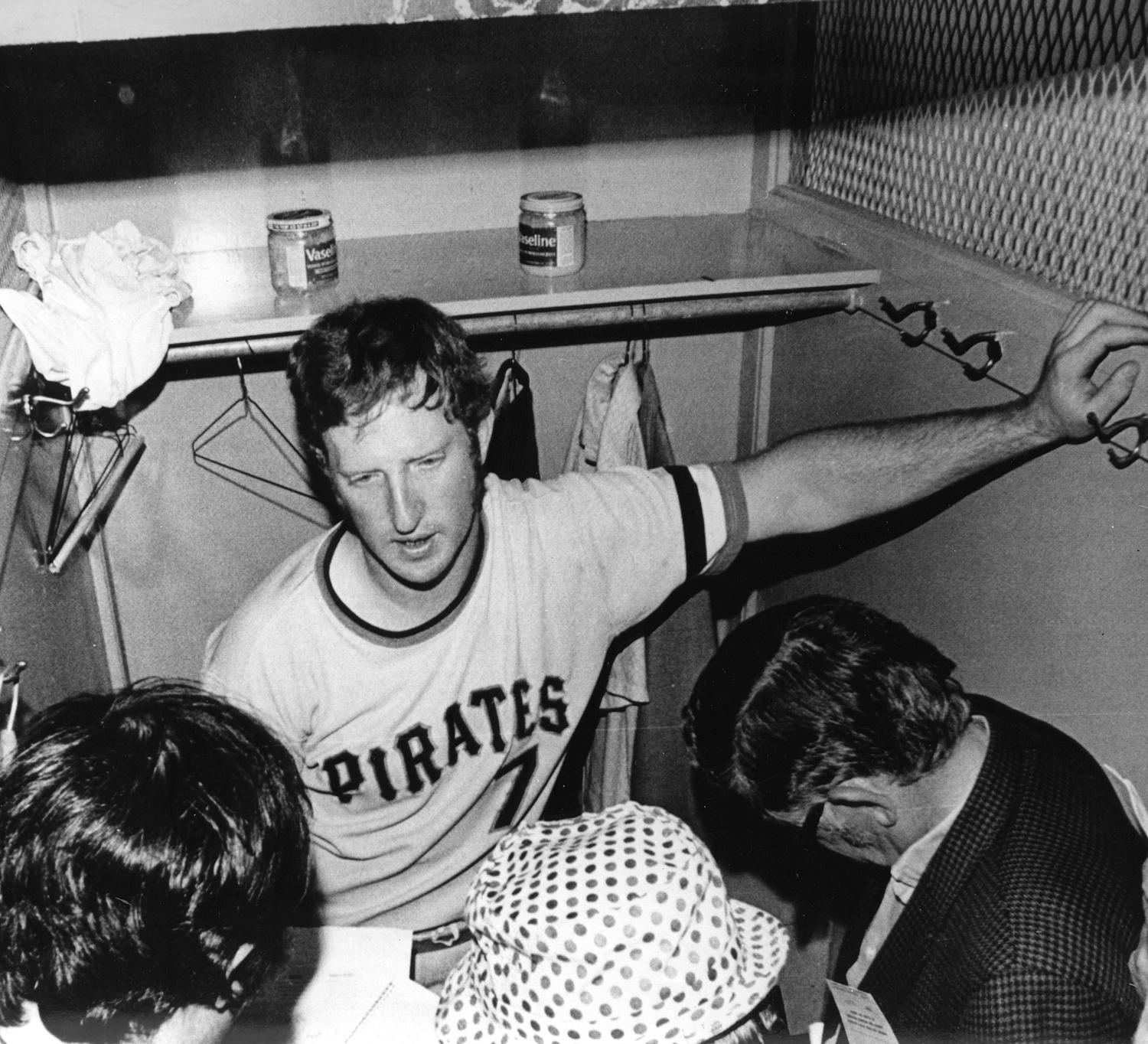

Not only did Robertson’s power production open eyes within the organization, but so did his work ethic and serious approach to the game. Robertson worked hard and played hard. His serious nature also contributed to a nickname in the Pirates’ clubhouse. Some of his Pirates teammates, legendary for their enthusiasm in needling others and making jokes, dubbed him with a nickname.

“I call him ‘Grumpy,’ ” Hall of Fame second baseman Bill Mazeroski told All Sports magazine in 1971. “He’s always walking around with a scowl on his face.”

If Robertson struggled through a bad game, he might show up the ballpark the next day in a tense mood. For his part, Robertson claimed that he wasn’t actually grumpy; he was just very serious about his job. “It’s all business, no pleasure with me,” Robertson informed Pittsburgh writer Jim O’Brien.

Robertson’s work ethic carried over to his defensive play. While he had limited range as a third baseman, he took pride in his efforts at first base. Although big and bulky, he owned surprising agility and soft hands.

Robertson became especially adept at pulling off one of the toughest plays in a first baseman’s playbook: the 3-6-3 double play. Opposing scouts raved about Robertson’s ability to pick up ground balls, pivot toward second base, and make accurate throws. Scouts instructed their hitters to bunt away from Robertson, and instead try to direct the ball toward third base or the pitcher.

Fully established as a first baseman, Robertson put up another good season in 1971. Still, there were obstacles. A variety of problems with his knees caused him to miss 31 games. The condition of his knees at least partially accounted for Robby’s long home run drought; he did not hit a single home run from Aug. 25 until the end of the regular season.

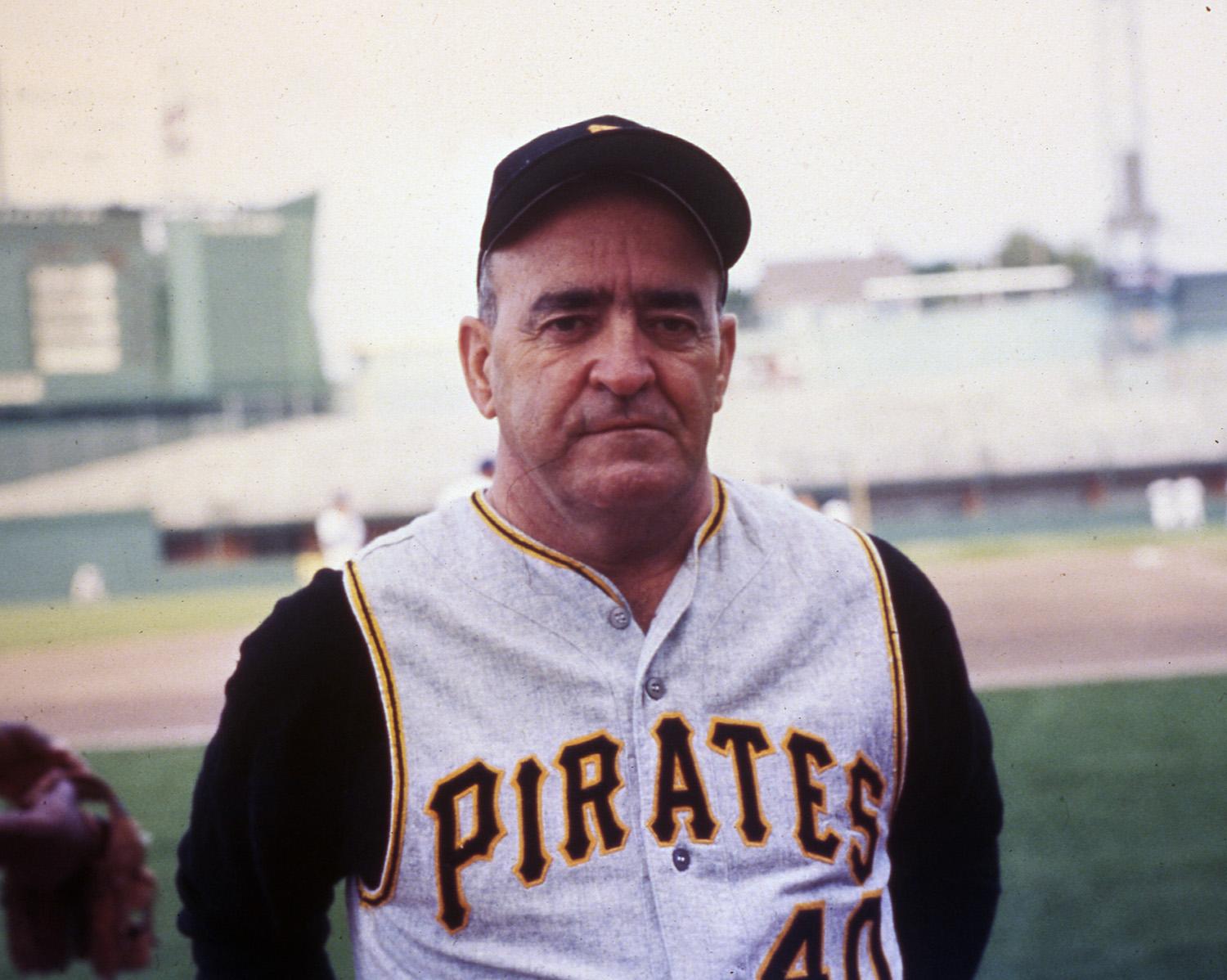

In Game 3 of the 1971 World Series, Pirates manager Danny Murtaugh called for Bob Robertson to bunt, but Robertson hit a home run instead. After Robertson apologized for the miscommunication, Murtaugh joked, "Under the circumstances, there will be no fine.” (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

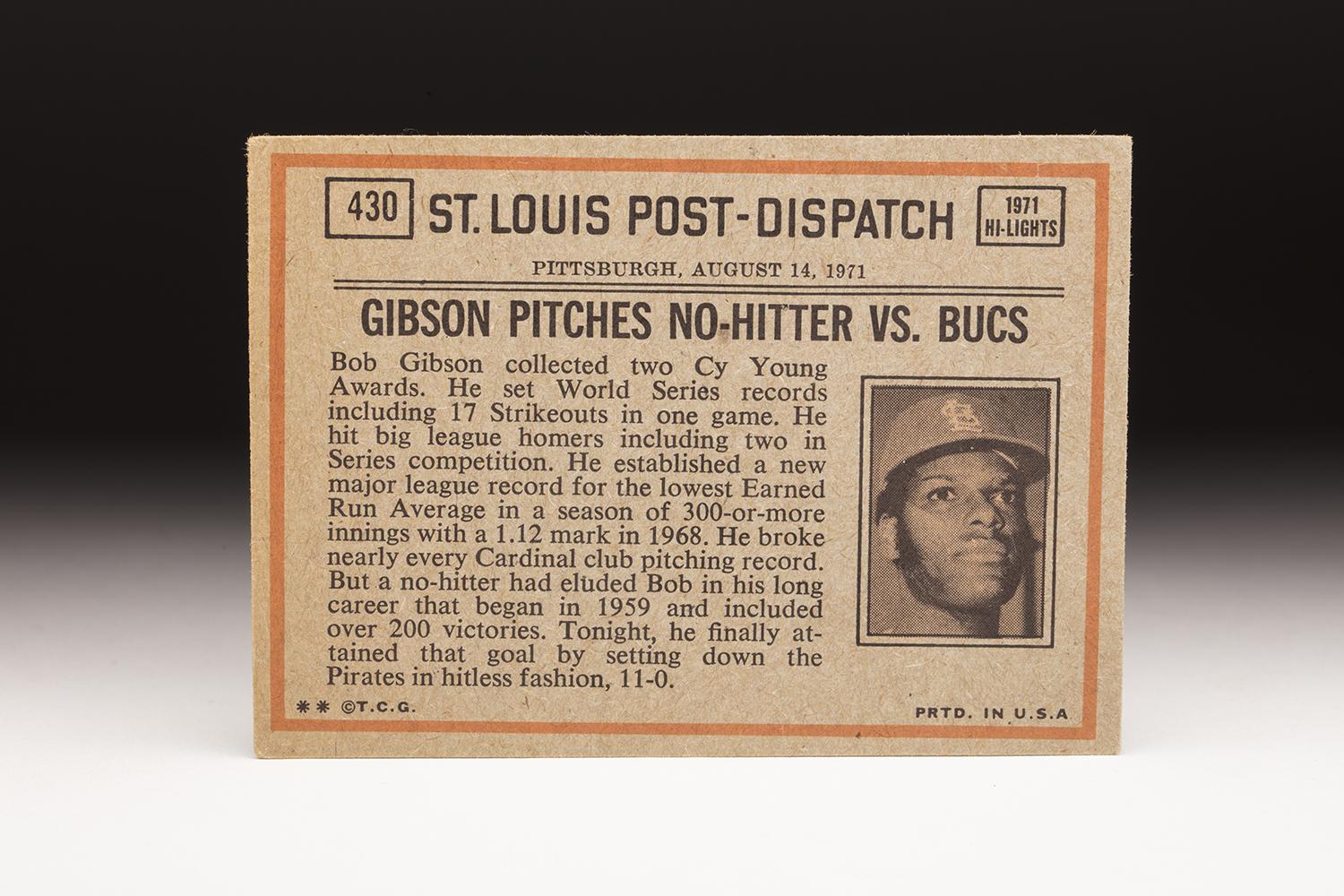

The home run tailspin finally ended in Game 2 of the NLCS against the Giants. After narrowly missing a home run and settling for a double in his first at-bat, Robertson came to bat a second time, with the Pirates trailing, 2-1. Robertson sliced a pitch from left-hander John Cumberland down the right field line, chasing Dave Kingman into the corner. Kingman raced to the Candlestick Park foul line, leapt for the ball, and appeared to make an impressive off-balance catch. But as he collided with the foul pole, the ball came loose and landed on the other side of the fence for a home run.

In the seventh inning, Robertson added a three-run homer against another lefty, Ron Bryant. And then came a solo shot against a third southpaw, Steve Hamilton, in the ninth, topping off a 9-4 blowout win for the Pirates. Robby’s sudden barrage made national news. Perhaps spearheaded by Robertson’s power surge, the Pirates went on to win the next two games and take the pennant. More spotlight moments would await in the World Series.

After dropping the first two games to the Baltimore Orioles, the Pirates faced a critical Game 3 at Three Rivers Stadium. With the Pirates leading 2-1 in the seventh, Roberto Clemente reached on an error and Stargell drew a walk. Robertson stepped into the batter’s box against Baltimore left-hander Mike Cuellar.

With the count one-and-one, Pirates manager Danny Murtaugh noticed that Brooks Robinson was playing deep at third for the Orioles. He signaled to Frank Oceak, his third base coach, calling for the slugging Robertson to lay down a bunt. For some reason, Robertson did not see the sign.

Instead of squaring to bunt, Robertson unleashed a full uppercut swing. He drove the ball deep toward right field. Several seconds later, the ball landed beyond the 385-foot sign at Three Rivers Stadium.

After Robertson crossed the plate, Willie Stargell wryly whispered to him, “Nice bunt, Robby.” Stargell’s comment tipped off Robertson to the fact that he had missed the bunt sign. Robertson jogged back to the dugout and turned to Murtaugh, saying sheepishly, “I guess I fouled it up, huh?” Murtaugh responded calmly, “Possibly. But under the circumstances, there will be no fine.”

Thanks in large part to Robertson, the Pirates won the game, and then took the third and fourth games, before squeezing out a 2-1 victory in Game 7. In so doing, the Pirates completed one of the largest upsets in Fall Classic history.

Now basking as world champions, the Pirates felt confident about their young first baseman. Some members of the media wondered if Robertson might be able to hit 50 home runs in a season. It seemed possible, but it would never happen. In fact, the Pirates had already seen the best of Robertson.

At the start of the 1972 season, Robertson struggled terribly. He remained in a slump for most of a long, unproductive summer. The season became more difficult when Bill Virdon, who had succeeded Murtaugh, decided to use Willie Stargell at first base, instead of the outfield. Virdon moved Robertson back to third base, where he platooned with Richie Hebner. Robertson also served as a backup first baseman and left fielder. Finding the part-time role disruptive, Robertson finished the season with a miserable .193 batting average.

In 1973, during the aftermath of the tragic loss of Roberto Clemente, the Pirates momentarily considered using Robertson as an outfielder, but ultimately returned him to first base. Then came a pivotal setback that would change his career. During a game at Wrigley Field, Robertson ran into foul territory in pursuit of a pop-up. As he approached the dugout, Robertson ran through a small puddle of mud and briefly lost his footing, slipping for just an instant.

After the game, Robertson’s right knee swelled up to the size of a softball. He had to resort to draining the knee each day. The Pirates’ medical staff eventually recommended that he undergo an operation to repair ligament damage. Robertson would undergo two more operations on the knee. He would also struggle with chronic back pain, which was so bad that he would have to endure three different surgeries. That made for a total of six surgeries.

The line of injuries undercut Robertson’s career, preventing him from becoming the next Kiner or the next Killebrew, as some scouts had predicted. After hitting 53 home runs in 1970 and ‘71, Robertson hit only 48 home runs over the span of the next four seasons. He was now a part-time player.

Robby remained in Pittsburgh through Spring Training of 1977. On March 31, the Pirates released their one-time slugger; Robertson responded by filing a grievance, claiming that he had an injured back and should have been placed on the disabled list, which would have entitled him to full pay. One day before the arbitration hearing, the Pirates agreed to give Robertson his full salary for 1977.

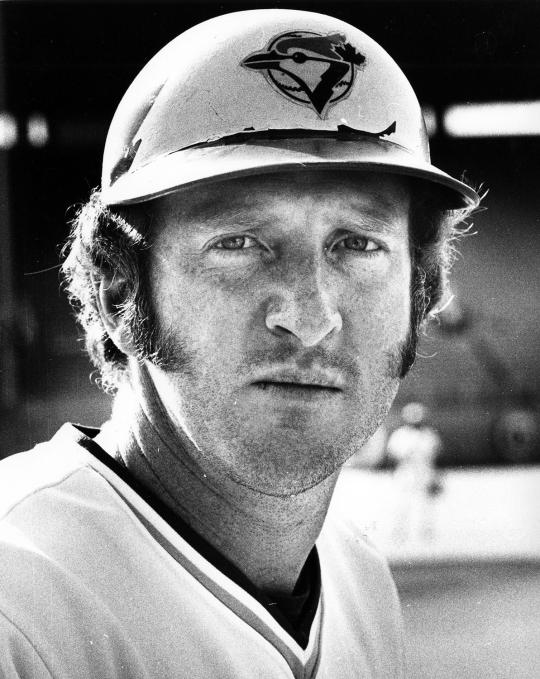

Robertson would have to settle for work with expansion teams. In 1978, Robby found a temporary home with the Seattle Mariners, who had just entered the American League in 1977. The Mariners thought that Robertson would be perfect for the friendly dimensions of the Kingdome and its foul poles, only 316 feet from home plate. But his back continued to bother him, preventing him from gaining a foothold in Seattle. He then spent a short time with the Toronto Blue Jays, another new franchise, but hit a meager .103 in 29 at-bats.

By this stage of his career, Robertson could not take extra batting practice or extra infield without his back locking up. Realizing that he simply could not play any longer, Robertson decided to retire, leaving the game at the age of 32.

His playing days over, Robertson turned to private business. He ran his own advertising agency and also hosted motivational seminars. Other than a brief stint as an Astros minor league hitting instructor in the early 1990s, he has mostly worked outside of the game. Yet, he has maintained a connection to baseball as an active participant in Pirates alumni events.

Years ago, I had the chance to cross paths with Robertson. Back in 1997, the Hall of Fame’s multimedia department was putting together a tribute video for beloved Museum executive Bill Guilfoile, who was retiring as the institution’s public relations director. Bill had previously worked with the Pirates as their PR man. In assembling the video, we interviewed a number of people whom Bill had worked with during his days in Pittsburgh. Robertson was one of those folks.

I can tell you that Robertson was easily one of the most cooperative, outgoing players of all those we met. He told us so many stories that showed the human side of the gentlemanly Guilfoile, who passed away in 2016.

By the way, Bob Robertson wasn’t grumpy at all that day. He still looked big, but not grumpy. Quite the opposite, he was cordial and fun.

Sometimes the nickname just doesn’t fit the player at all.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame