- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1972 Topps Phil Regan

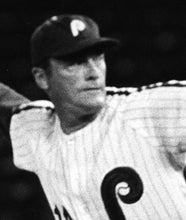

#CardCorner: 1972 Topps Phil Regan

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

Clichés have long inhabited baseball. One of the standby sayings goes something like this: “Baseball is a young man’s game.” Like a lot of clichés, it rings mostly true.

Statistical surveys, championed by the likes of Bill James, maintain that most players enjoy their prime seasons when they are 27 or 28 years old. Increasingly, major league teams have turned to youth, eschewing older free agents in their 30s for young, untested, and unproven players in their 20s. Younger players not only seem to possess greater athletic skills – and therefore the ability to produce more – than their thirtysomething counterparts, but they generally come less expensive in a game where longevity can lead to a more lucrative paycheck.

Official Hall of Fame Apparel

Proceeds from online store purchases help support our mission to preserve baseball history. Thank you!

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Younger managers have also become part of a trend. It used to be commonplace to see managers in their 60s, even occasionally in their 70s. In today’s game, there are no managers who are 70 or older, while only eight of the 30 managers are 60 or older. (At 65, Joe Maddon of the Chicago Cubs is the dean of current day skippers.)

In today’s game, it is more common to see managers in their 40s (there are currently 12), some of whom have been hired with little prior managerial experience. The belief is that more youthful skippers are more open to accepting analytics and are also better suited to the rigors of a long season, better at relating to younger players, and more equipped to handle the demands of the modern media.

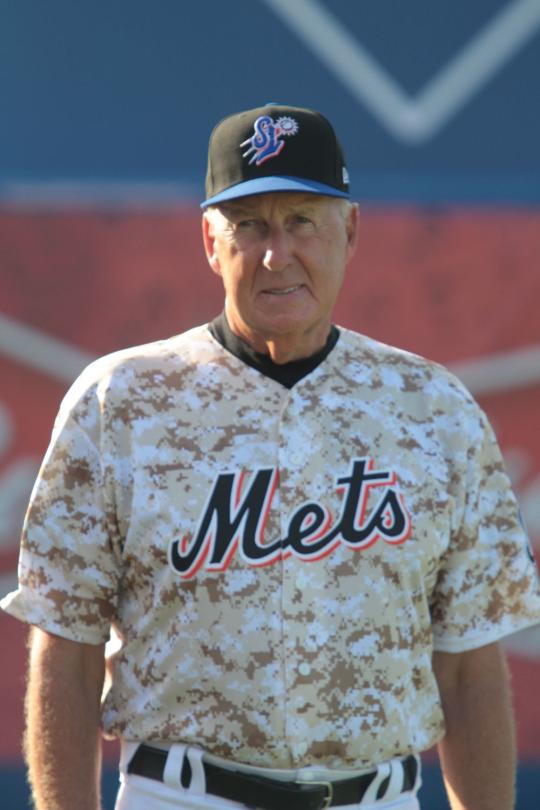

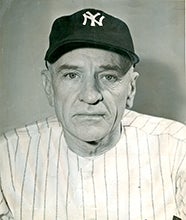

That’s the landscape of baseball today. And then comes along an 82-year-old baseball lifer named Phil Regan, who put at least a temporary halt to the trend earlier this season when the New York Mets hired him as a midseason replacement to their staff. Regan is not a player (obviously) or a manager – at least not any more – but he is the Mets’ pitching coach. Back in June, the Mets brought him in to replace the 53-year-old Dave Eiland.

The decision to hire Regan was mocked by some of the New York media, but Regan paid little attention to the mocking. Under Regan’s watchful eye, the Mets’ pitching staff, both in terms of the bullpen and the starting rotation, has improved. Regan seems to be having an impact, though he’s not just doing it with old school techniques. Rather, Regan has found success with a mix of old school wisdom and new school analytics, which he embraces openly. He’s also relied on his knowledge of current Mets pitchers, many of whom he coached when they came up through the club’s farm system.

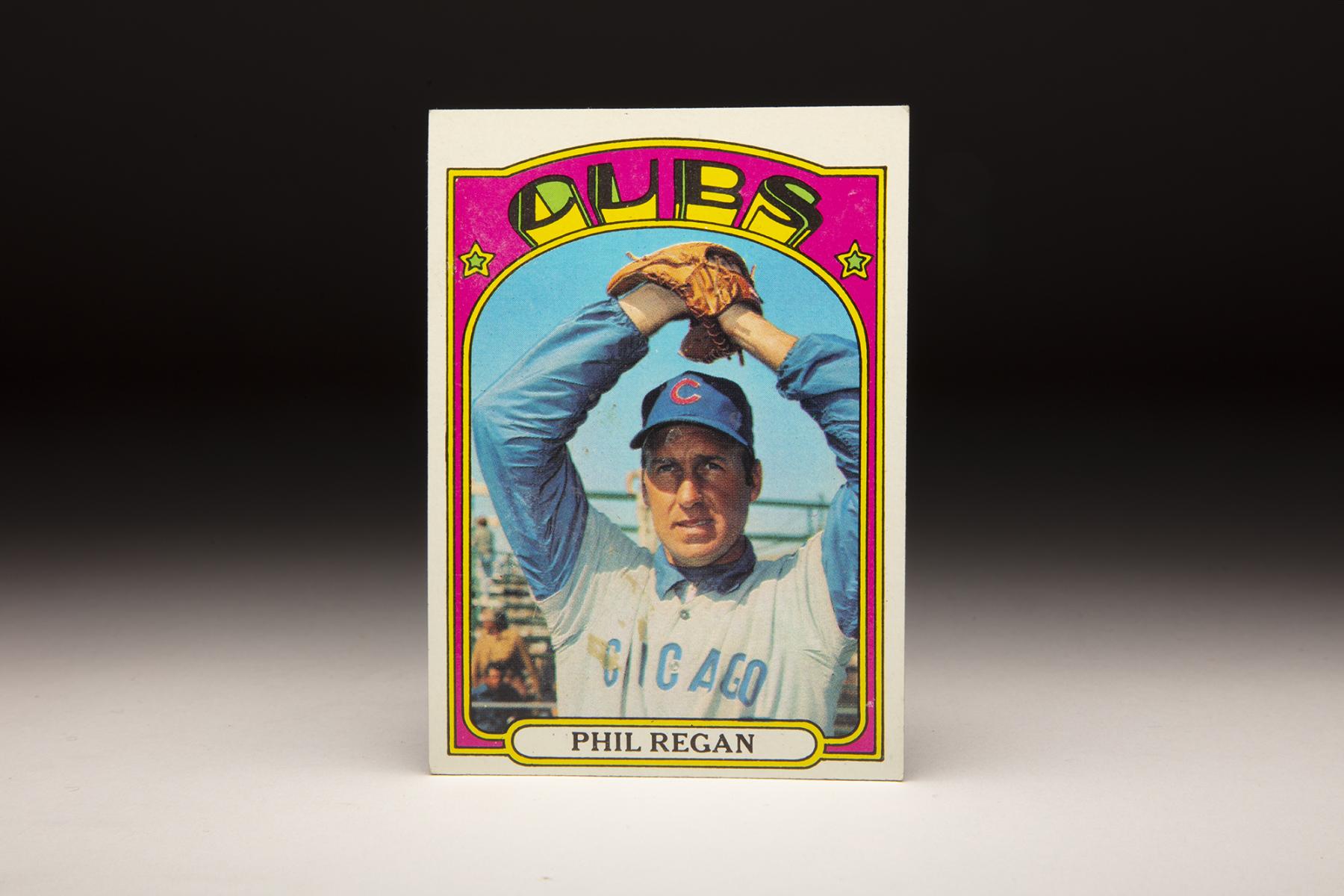

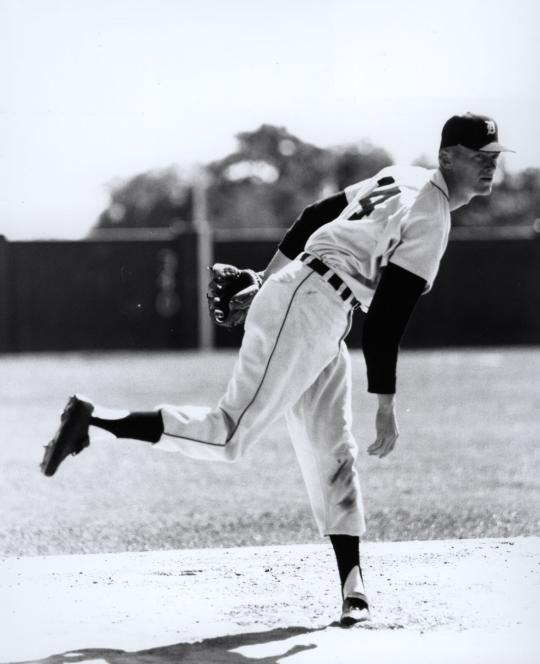

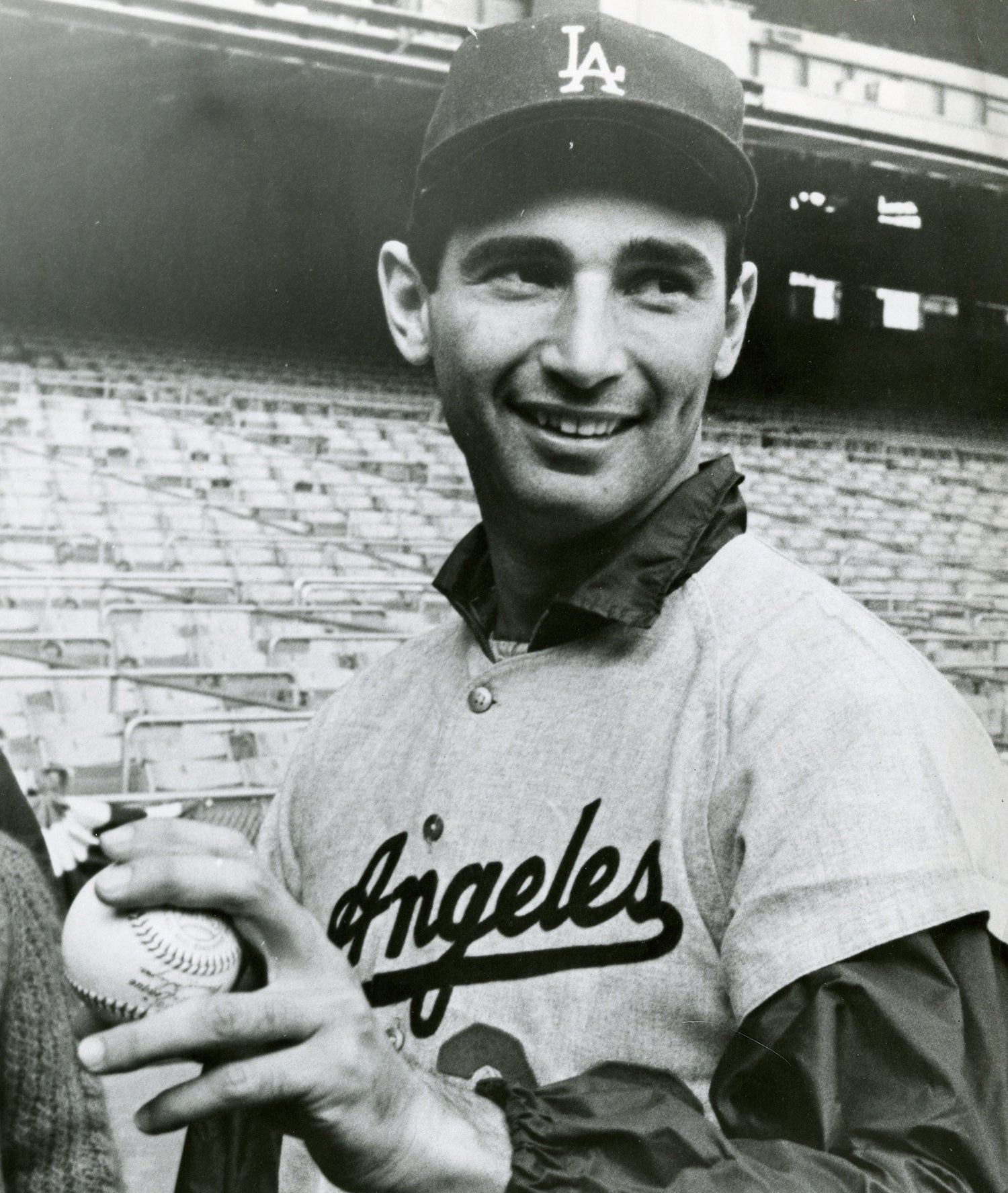

Regan was a pitcher himself – as evidenced by the pose on his 1972 Topps card – and a good one. In fact, he was an excellent all-around athlete at the amateur level. At Michigan’s Wayland Union High School, he starred in three sports, including football and basketball. But it was his pitching that drew the attention of the nearest major league team, the Detroit Tigers. After Regan attended Western Michigan University for one year, he signed his first professional contract with the Tigers in 1956.

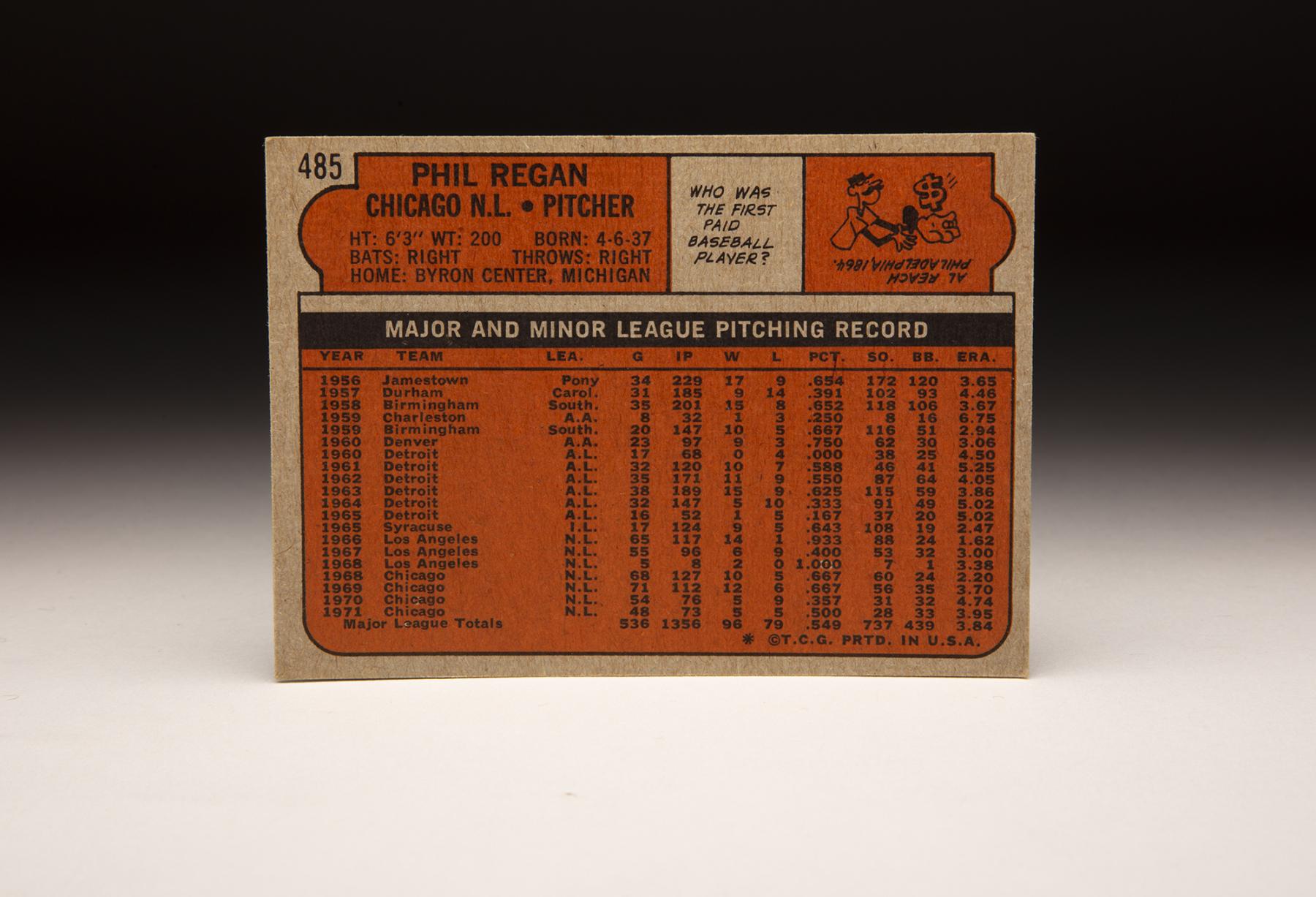

Regan worked his way methodically through the Tiger farm system making stops in Jamestown (N.Y.), Durham, Birmingham and Denver before finally earning a promotion to the Tigers’ roster in the middle of the 1960 season. (His first major league manager became Jimmy Dykes, a longtime baseball man who was born in 1896. That allows us to make a connection between Regan and the 19th century.) Using the 23-year-old right-hander as both a reliever and starter, the venerable Dykes watched Regan struggle as a rookie. Pitching a total of 78 innings, he lost all four of his decisions while sporting an ERA of 4.50.

Though Regan was not overly impressive, the Tigers felt that he could contribute as a long reliever and spot starter in 1961. He made the team out of Spring Training, but fared even worse in his sophomore season than he had as a rookie. In 120 innings, he struck out 46 batters while walking 41. His ERA rose to 5.25, a mark that was likely pushed higher in an expansion season that was dominated by hitting and home runs.

In 1962, the Tigers gave Regan a chance to start more often. In 23 starts, he pitched to an ERA of 4.02 while winning 10 of 17 decisions. The following season, he took on a greater role in the starting rotation, winning 15 games and striking out 115 batters. Regan ranked as the No. 3 starter on the Tigers, behind future Hall of Famer Jim Bunning and left-handed ace Hank Aguirre.

Still only 26 years old and possessing a good sinking fastball and a deceptive slider, Regan appeared to have settled in as a longtime starter in Detroit. But the 1964 season saw him endure a setback. With an ERA that jumped over 5.00, Regan won only five games and lost 10. Within the Tigers’ rotation, two young starters and future aces, Mickey Lolich and Denny McLain moved ahead of Regan in the pecking order.

The situation only worsened in 1965. Regan pitched so poorly at the start of the season that the Tigers sent him to Syracuse, their Triple-A affiliate.

While Regan might have thought that he had left minor league ball for good, he was now facing the reality of a return to life in the bush leagues – and an encounter with an old ballpark in Syracuse.

“The thing I remember about MacArthur Stadium was that at about nine o’clock at night the mosquitoes came out,” Regan told Syracuse.com in a recent interview. “They tell me it was built on a dump, the ballpark was. I’m telling you, there was some big mosquitoes there, too. They used to light fires in the bullpen to smoke them out and things like that to keep them away.”

While swatting away mosquitos, Regan learned to throw a new pitch during his time in Syracuse: It was a pitch that would help make him effective once again: a “greaseball.” Given the illegal nature of the greaseball, Regan and the Tigers did their best to hide the identity of the pitch.

Regan dominated at Triple-A Syracuse, but the Tigers remained concerned about his long-term potential, even with the aid of a greaseball. That winter, the Tigers shopped Regan and found a taker in the Los Angeles Dodgers. In exchange for Regan, the Tigers picked up utility infielder Dick Tracewski.

The trade would turn out to be a boon for the Dodgers. Recognizing that Regan’s repertoire of pitches didn’t stand up well over eight or nine innings, Dodgers manager Walter Alston made a wise decision in converting him to the bullpen.

In short time, Regan became the Dodgers’ relief ace, posting an ERA of 1.62 and a remarkable WHIP (walks and hits over innings pitched) of 0.934. Regan also led the National League with 21 saves and added 14 wins against one loss.

On several occasions, Regan entered games in which the Dodgers were tied or trailed, quickly saw the Dodgers take the lead, and then held on to emerge with a victory. In one game, Regan relieved Sandy Koufax, who had pitched brilliantly for eight innings but left the game with a 1-1 tie. Regan then came in, the Dodgers scored, and Regan picked up the win. He also picked up the nickname, “The Vulture,” in the process.

“When I came into the clubhouse, Koufax said, ‘Regan, you’re a real vulture getting my wins like that,’ ” Regan told David Laurila of Fangraphs. “A reporter heard that, and it went from there. I must have gotten a thousand of these little rubber vultures that people would send me. A zoo was even going to put a [live] vulture in the bullpen, but the Dodgers, or somebody, wouldn’t let them do it.”

Still, the colorful nickname would stick with Regan for the balance of his career.

Some fans and media members referred to the nickname in a derisive fashion, but the voters for National League MVP held a different opinion. They voted Regan a seventh-place finish, an unusually high placement for a relief pitcher of that era. Regan would also win Comeback Player of the Year honors.

More importantly, Regan received a chance to participate in his first postseason. After winning the pennant, the Dodgers faced the Baltimore Orioles in the World Series. The Dodgers would lose all four games, but Regan pitched scoreless relief in each of two Series appearances.

Regan did not pitch as well in 1967, losing the relief ace role to left-hander Ron Perranoski. Still, he gave the Dodgers 96 innings of good relief while keeping his ERA under 3.00. He also furthered his reputation as a thrower of the greaseball, or spitball.

That summer, Sports Illustrated featured an article claiming that as many as 25 percent of major league pitchers threw a spitball in 1967. The article also mentioned four of the leading practitioners of the spitball, naming Don Drysdale, Gaylord Perry, journeyman righty Bob Shaw and Regan.

A reporter then asked Regain if it was true that he threw a spitter. Offering a diplomatic answer that sounded almost Stengelese in tone, Regan told the writer, “I can’t come right out and tell you that I now throw the spitter, but I’d say I don’t use it nearly as much as everybody thinks.”

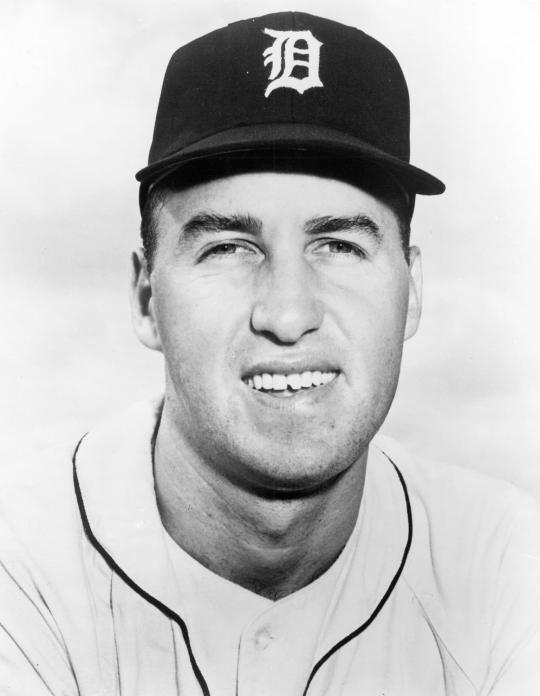

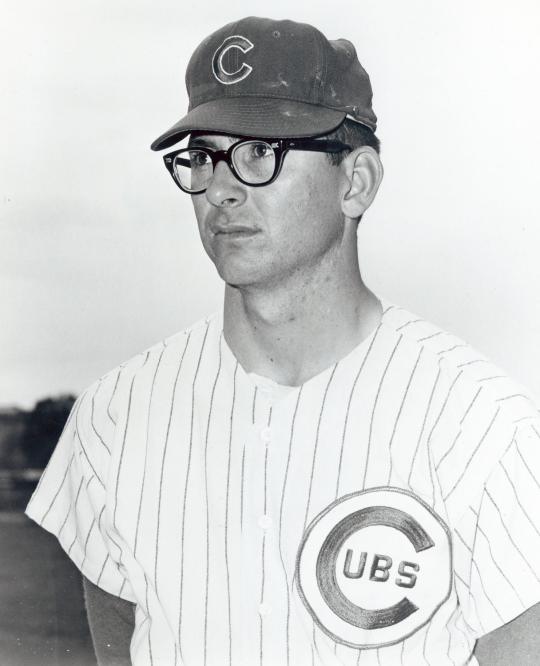

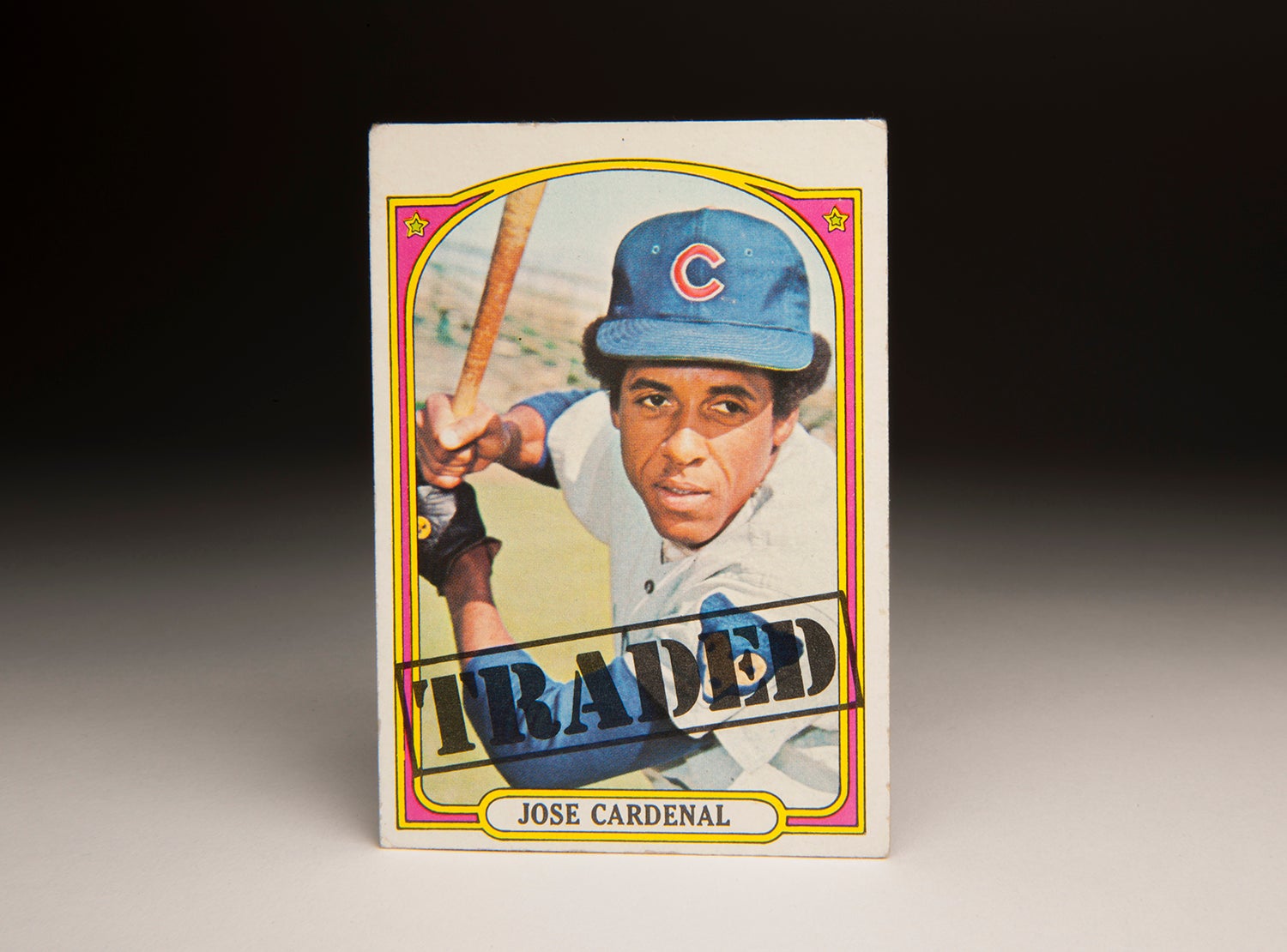

Regan continued to pitch well for the Dodgers at the start of 1968, but with Perranoski also around, the Dodgers had the luxury of two standout, late-inning relievers. Hoping to strengthen other areas of the club, the Dodgers made a trade in late April, sending Regan to the Chicago Cubs in a deal for outfielder Ted Savage and left-hander Jim Ellis.

The Cubs gladly made Regan their relief ace (or closer, in today’s parlance) and watched him save 25 games over the balance of the season. Even with a late start on closing games that summer, Regan earned his second National League Fireman of the Year Award.

Regain remained effective in the relief ace role in 1969, even as the Cubs squandered a sizeable midseason lead over the upstart Mets. Ever the workhorse, Regan appeared in 71 games and logged 112 innings. Some observers of the Cubs felt that Regan was overworked, hurting his performance out of the bullpen during the final two months of the season.

The toll of the 1969 season may have been felt the following year, too. Now 33, Regan saw his ERA balloon to 4.76, his worst mark since his days in Detroit. He eventually lost the role of closer and moved into long relief.

In 1972, Regan appeared on his final Topps card as a player. The photo shows him in Spring Training (presumably during 1971) feigning his windup while wearing his road Cubs jersey over a windbreaker. That latter fashion choice was a common look for players in Spring Training, perhaps a way to sweat off some pounds after the long winter.

Yet it is Regan’s face that has always stood out to me. With his roundish, sun-bleached look, Regan appears much older than his actual 34 years. When I first saw this card many years ago, I would have guessed he was at least 40 in this photo. Then again, a number of players from the 1960s and 70s look older on their cards than their counterparts of today. I’ve heard it said that the proliferation of day games in the 1960s, at a time when sunscreen was not as effective as it would later become, contributed to a more weathered look for players. Perhaps there is something to this.

Regan’s 1972 Topps card would become dated by June, when the Cubs sold his contract to the cross-town Chicago White Sox. Called on only 10 times over the span of seven weeks, he drew his release on July 20, ending his career after 13 seasons.

Regan went home to Michigan and began working as the head coach at Grand Valley State University. He remained there through 1982, when he returned to professional baseball as a minor league coach with the Seattle Mariners. From there, he took a job in the Dodgers’ organization as a scout. He then found his true niche working as a major league pitching coach, first with the Cleveland Indians and later with the Baltimore Orioles and the Cubs. In 1995, the Orioles gave him a chance to manage the team, albeit for just one season.

Regan then found work as a minor league instructor for the Tigers before joining the Mets as a roving pitching coach. He continued to toil quietly away from the spotlight, until the Mets made news when they announced his hiring as their new pitching coach.

Forty-seven years after appearing on a baseball card that made him appear older than he was, Phil Regan is still going strong at the age of 82.

The Vulture is proving that baseball needs the wisdom of its older guys, too.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame