- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1972 Topps José Cardenal

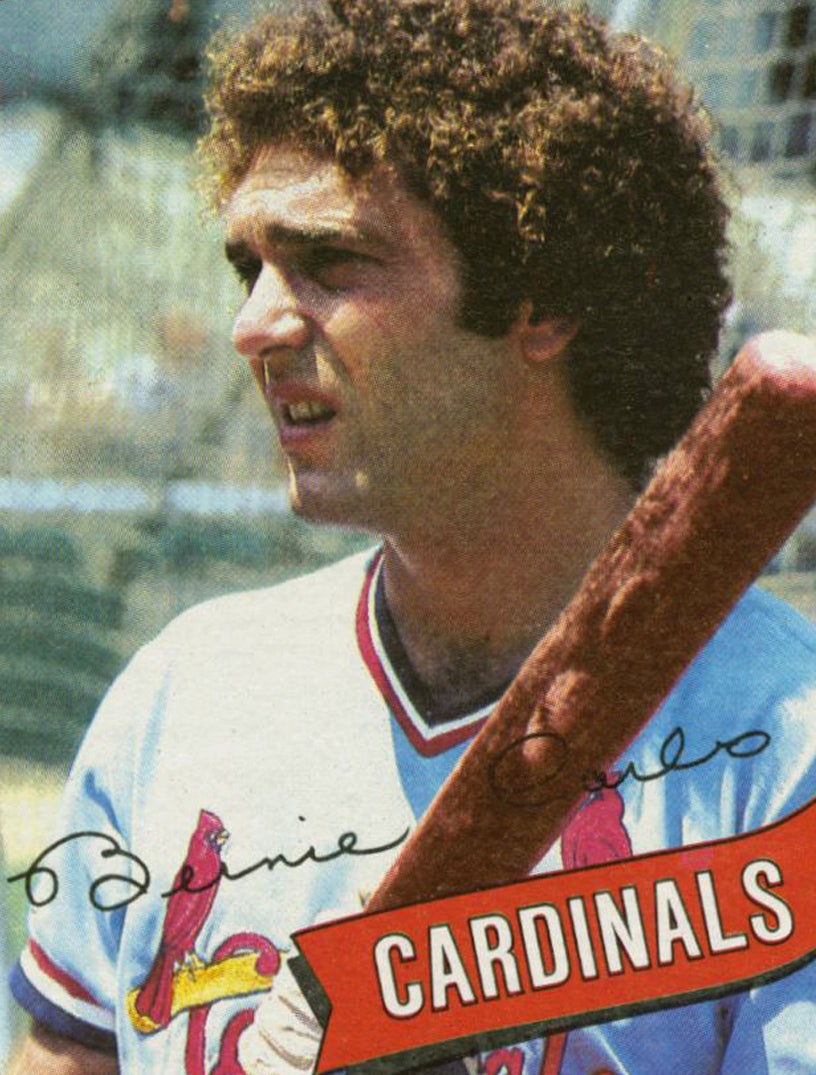

#CardCorner: 1972 Topps José Cardenal

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

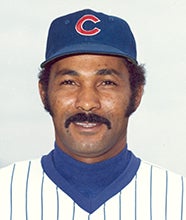

With the Chicago Cubs and the Cleveland Indians squaring off against each other in this year’s World Series, it only seems appropriate that #CardCorner should feature a well-traveled player who performed for both teams. He played for one franchise in the 1960s, another in the 70s, and a whole of lot of others along the way. He also happens to be one of my favorite characters, a colorful fellow and baseball lifer known as José Cardenal.

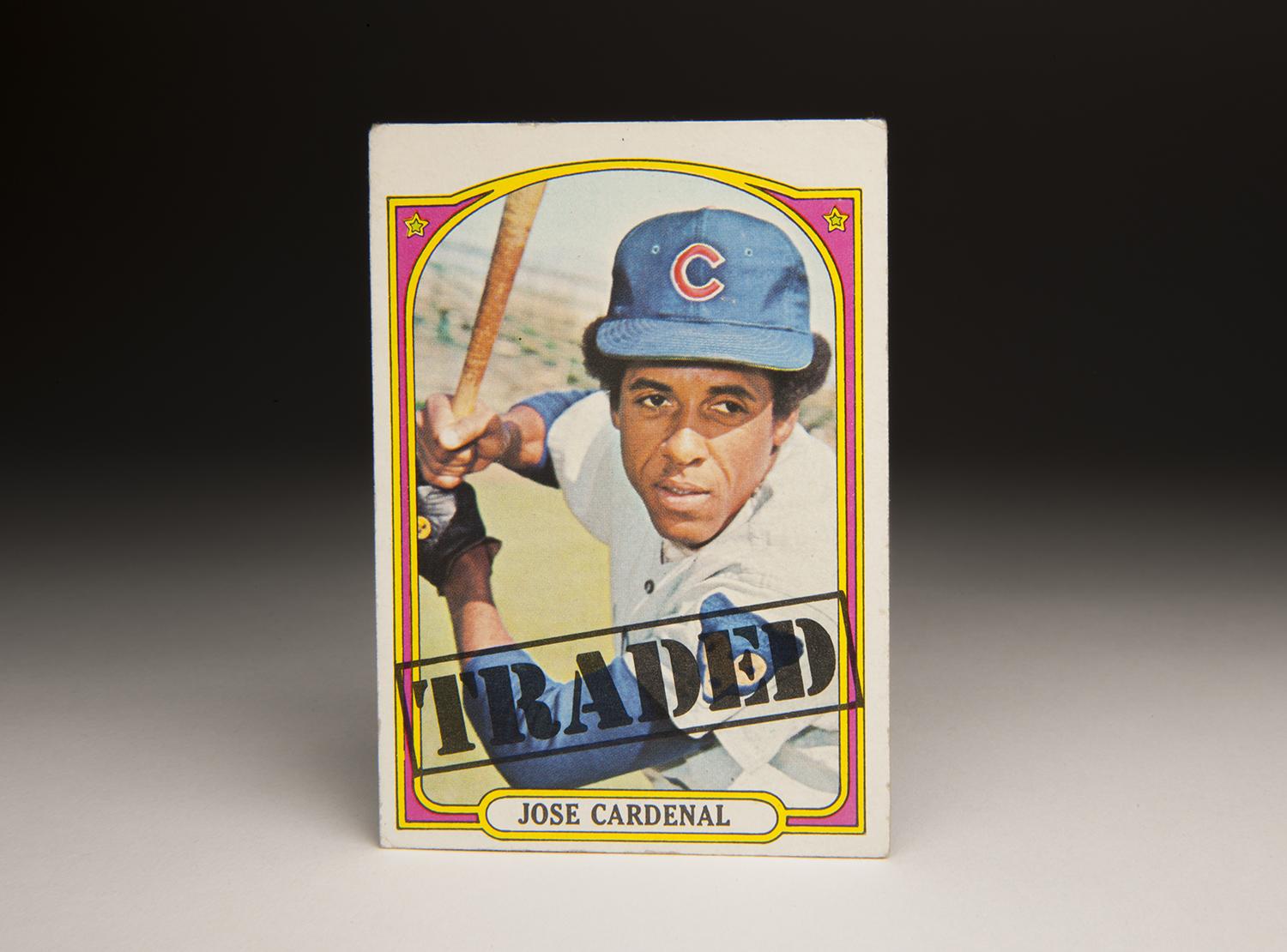

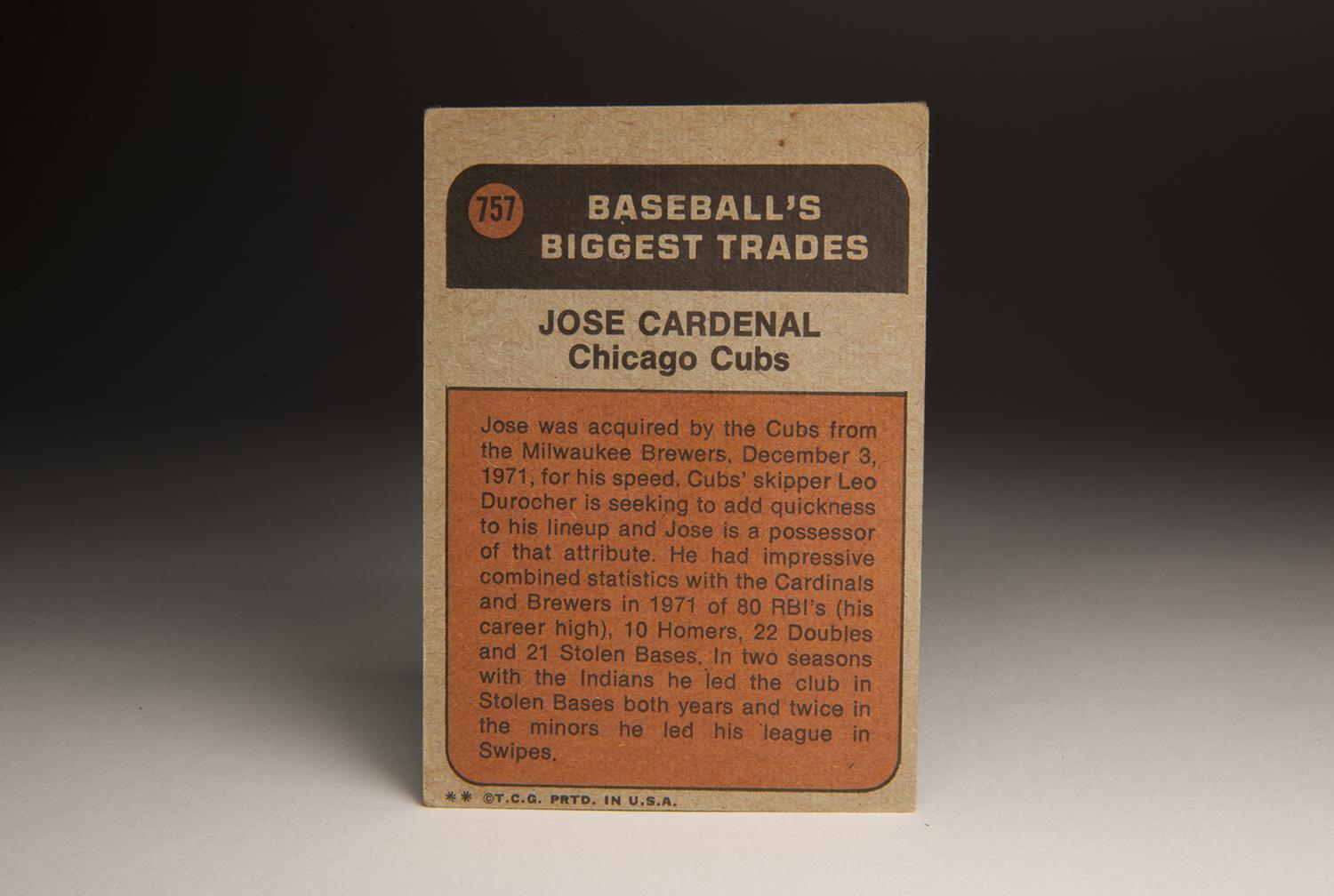

I collected my first card of Cardenal in 1972. Actually, the 1972 Topps set featured Cardenal on two different cards. His base card, the easier of the two to obtain, shows him with his 1971 team, the Milwaukee Brewers. After the ’71 season, the Brewers dealt him to the Cubs for outfielder Brock Davis and right-hander Jim Colborn. That trade made Cardenal’s base card somewhat outdated. Lo and behold, Topps had decided to experiment with something different in its 1972 set. For the first time in its history, Topps issued a series of “Traded” cards, which showed players who had recently been dealt, either during the winter or the spring, wearing the colors of their new teams. Included among the “traded” cards was an updated card of Cardenal, now wearing his new Cubs road uniform. That’s a high-numbered card, one that is a little bit more difficult to find on the market.

Topps’ decision to include “Traded” cards was likely a response to criticism that their cards were sometimes so dated that they did not reflect wintertime trades and other forms of player movement. Generally speaking, the first series of cards came out in February, right near the start of Spring Training. That didn’t give Topps the time to update their cards properly. Since traded players didn’t usually wear their new uniforms until Spring Training, there was little chance to showcase players with their new teams. (Of course, Topps did resort to airbrushing new colors onto old uniforms, but that often produced strange-looking cards.) But with Topps issuing other series of cards later in Spring Training, and even during the regular season, the company did have an opportunity to update the cards for some players. Topps seized that opportunity during the summer of ’72.

The Traded cards certainly had a distinctive look. While the colored frame around the border of the card remained, Topps removed the team name, which was normally presented in large, shadowed lettering, from the top of the card. The player’s name remained, in small lettering, at the bottom of the card. Now overshadowing the player’s name was the word “TRADED,” displayed at an angle and looking like it had been stamped with black ink onto the face of the card. This was a highly creative effort by Topps, one that gave the cards an improvised look. Believe me, young collectors in 1972 thought these stamped Traded cards were just about the coolest thing in cardboard.

In creating its subset of “Traded” cards, Topps was very selective. The company included six players: Steve Carlton, Jim Fregosi, Denny McLain, Joe Morgan, Frank Robinson and Cardenal. All were veteran players, all were brand names, and three of them were in the midst of Hall of Fame careers. Of the six, Cardenal might have been the least known. He also might have been the most colorful.

For a player like Cardenal, a Traded card was most fitting. After all, he had played for five franchises already, and would continue to move from team to team during the course of his lengthy career. He knew all too well what it was like to be traded, and the impact that it had in uprooting a player and his family. Despite the recent upheaval, Cardenal looks fairly relaxed on his Traded card, as he provides the photographer with a batting pose during Spring Training in Arizona.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

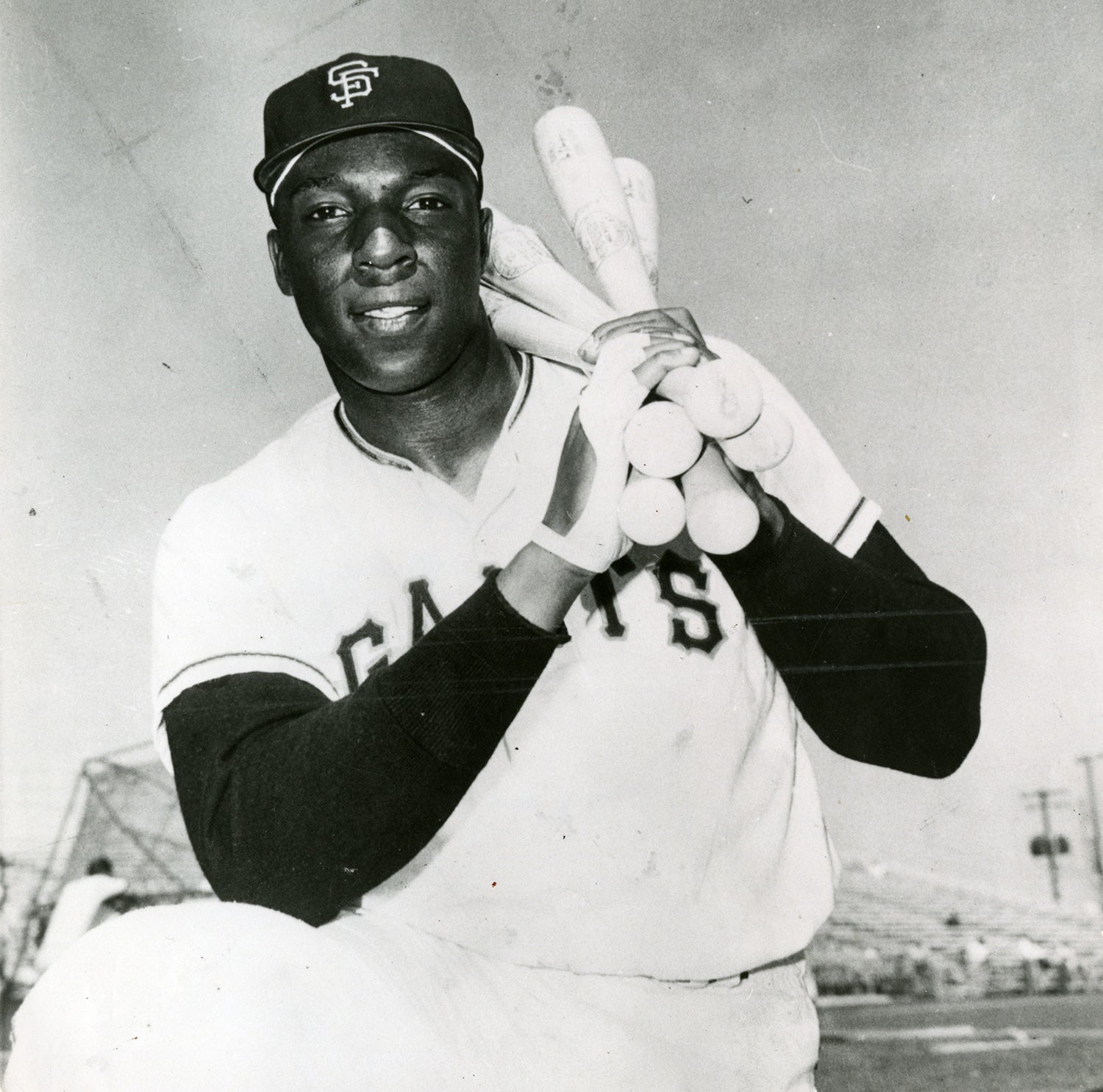

At one time, Cardenal seemed destined for superstardom, not for a well-traveled career that saw him make stops in St. Louis, Cleveland, Milwaukee, Chicago, Philadelphia, New York and Kansas City. In 1960, the San Francisco Giants signed him out of Cuba, making him one of the last players to leave the island before the restrictions created by the Castro/US conflict. By 1963, he was putting up huge numbers for Double-A El Paso. He hit 36 home runs, slugged .617, and stole 35 bases.

The Giants regarded Cardenal as a top-tier prospect who had speed, power, and the skills to play center field. A five-tool player, Cardenal had no discernible weakness in his game. His only mistake was playing for an organization that already had Willie McCovey, Willie Mays, and Felipe Alou in the outfield, with young talents like Matty and Jesus Alou, Bobby Bonds, Jim Ray Hart on the way.

Latino players dealt with many challenges in the major leagues, including the Giants. A common and unfair stereotype of Latino ballplayers in the 1960s charged them with being hotheads, unable to hold their temper.

For the most part, Cardenal played it cool, but he did lose his temper on at least one occasion. According to a story told by author Dan Epstein, Cardenal found himself being thrown at repeatedly by opposing pitchers in the Texas League. Playing for El Paso, he believed that the frequent knockdowns and beanball attempts were motivated largely by the color of his skin.

Perhaps influenced by Cardenal’s display of anger, the Giants decided to move him in a trade in November of 1964. They sent Cardenal to the Los Angeles Angels for a back-up catcher named Jack Hiatt. It was a puzzling move at the time, and remains so to this day.

The trade turned out to be the break that Cardenal needed. With a lack of quality outfielders, the Angels had plenty of playing time for Cardenal. The trade also gave him a chance to play against his cousin, Bert “Campy” Campaneris, the starting shortstop for the Kansas City A’s. In a game in late September of 1965, Cardenal became the first batter to step in against his cousin when Campy pitched as part of Charlie Finley’s nine-positions-in-a-day stunt. It was a remarkable coincidence.

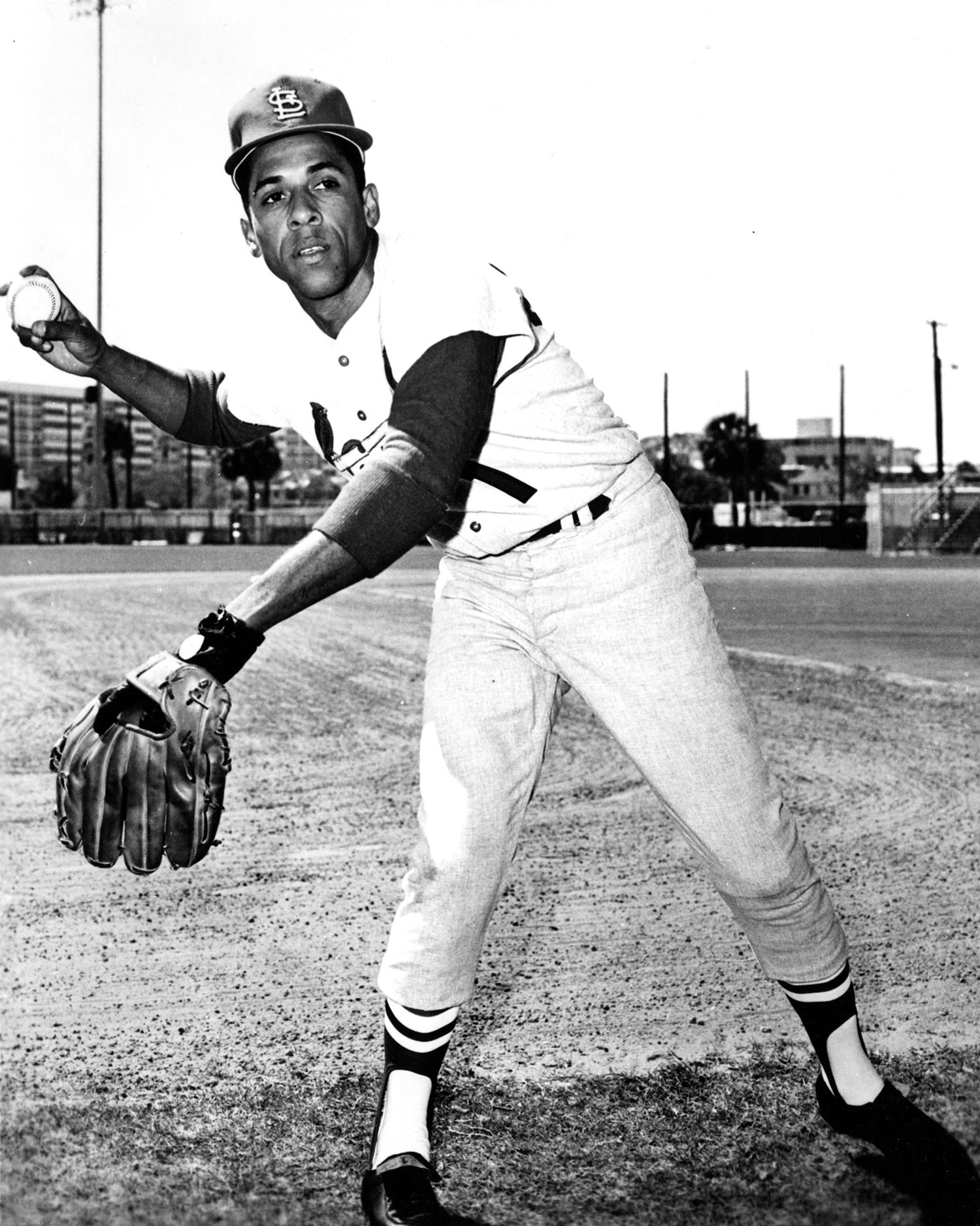

Cardenal showed promise with the Angels. In 1966, hit 16 home runs. But a poor performance in 1967 soured the Angels, who traded him to the Indians for infielder/outfielder Chuck Hinton. Cardenal played a capable center field and stole 76 bases over two seasons with the Indians, but his hitting production lagged. Looking for an outfielder with more punch, the Indians swapped him to the St. Louis Cardinals, in a straight-up trade for veteran outfielder Vada Pinson.

By now, Cardenal had started to establish his reputation for quirky behavior. For example, he liked to wear his uniform pants extremely tight, even though most players of the day wore flannels that looked loose and baggy. According to Seattle Pilots right-hander Fred Talbot, who was quoted by Jim Bouton in his classic Ball Four, Cardenal once sat out three straight games in winter league play because he could not find pants that were tight enough around his legs. That’s “did-not-play” because of loose pants.

In moving on to St. Louis, Cardenal became “Cardenal the Cardinal,” creating some marketing possibilities for the franchise. The Cardinals, playing half of their games on the expansive artificial turf of Busch Stadium, seemed like an ideal fit for a fast flychaser like Cardenal. With Cardenal in center and Lou Brock in left field, the Cardinals featured speed galore. Cardenal hit respectably for the Cardinals in 1970, but after a slow start to the 1971 season, he was on the move again. The Cardinals dealt him to the Milwaukee Brewers as part of a five-player deal that brought back middle infielder Ted Kubiak.

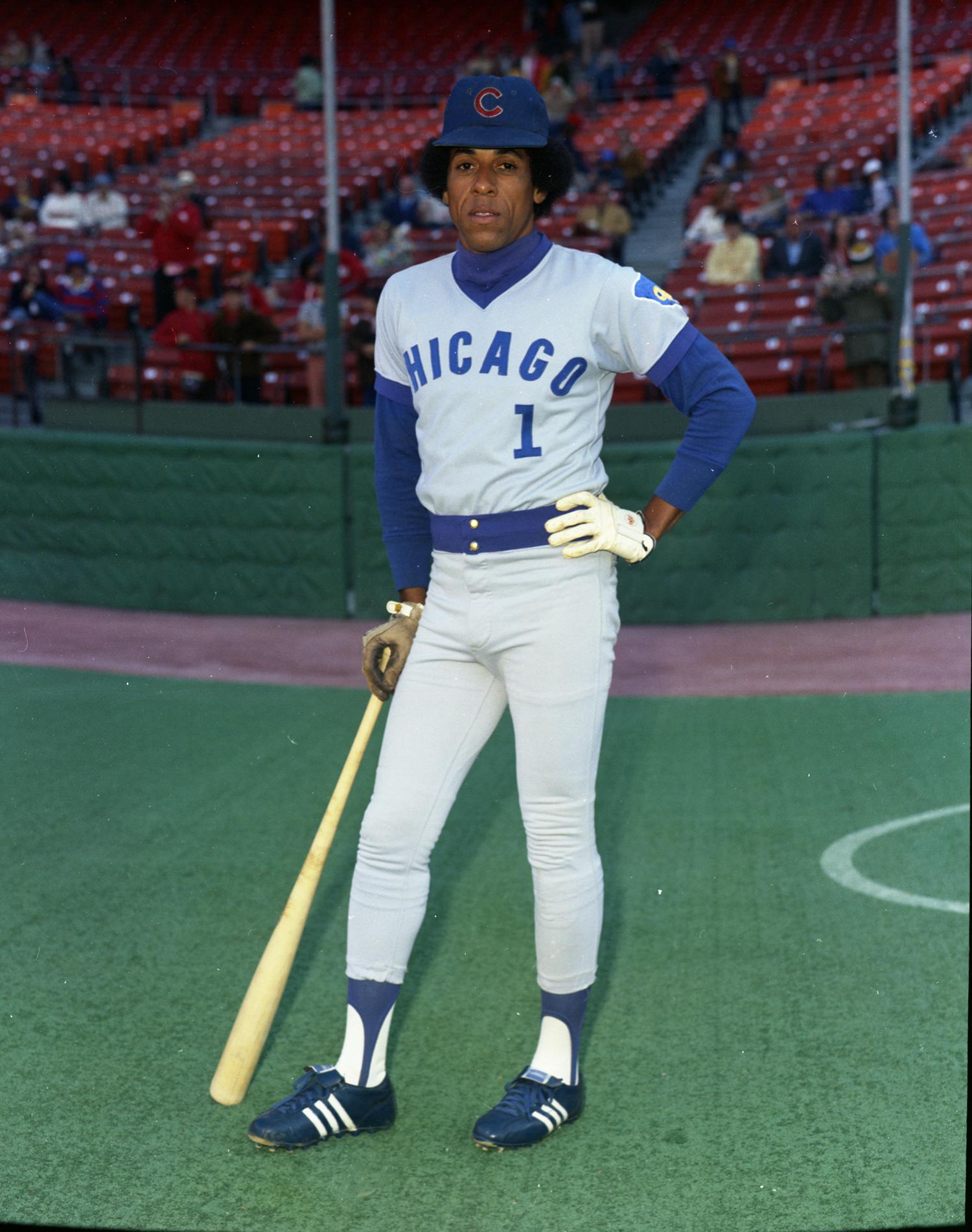

Cardenal played poorly during a half season with the Brewers. After the 1971 season, the Cubs acquired him in return for a package of three players, including Colborn and Davis. With Billy Williams in left field, Rick Monday in center, and Cardenal putting his speed and throwing arm to good use in right field, the Cubs assembled one of their best outfields in years. Cardenal would remain a fixture in front of the Wrigley Field ivy for six seasons.

In each of his first four seasons in the Windy City, Cardenal put up an OPS of over .800, including two seasons in which he received back-of-the-ballot consideration for National League MVP. In 1973, he led the Cubs in batting average and emerged as the team’s player of the year. Two years later, he batted a career-high .317 and drew 77 walks, the latter a career high. An underrated player, Cardenal became one of the National League’s better corner outfielders.

Culturally speaking, Cardenal also began to establish a unique physical appearance during his days in Chicago. He gradually started to grow out his hair longer. By the mid-1970s, Cardenal had established one of the largest Afros in the game, second only to Oscar Gamble (another former member of the Cubs and Indians). By the end of a typical game, Cardenal’s cap and helmet had left a notable indentation in his massive hair.

While playing for the Cubs, Cardenal became legendary for concocting strange excuses for an inability to play. In addition to his preference for skin-tight pants, there were bizarre eye injuries and nighttime distractions created by thoughtless crickets. During his first season with the Cubs, Cardenal claimed that he couldn’t see properly. The reason? He had woken up with his eyelid and his eyelashes stuck to his eyeball. “I woke up and my eye was swollen shut,” Cardenal explained to a reporter. “My eyelashes were stuck together. I couldn’t see, so I couldn’t play.”

One Spring Training with the Cubs, Cardenal told Cubs manager Jim Marshall that he couldn’t play in an exhibition game because some particularly loud crickets had kept him up the entire night. Marshall didn’t believe him, but gave the veteran outfielder the day off anyway.

By the end of the 1977 season, the Cubs realized that the aging Cardenal was no longer an everyday player. After the season, they traded him to the Philadelphia Phillies, where he struggled in a bench role. In 1978, the Phillies traded him to the New York Mets, where he played parts of two seasons as a utility outfielder. Then came a last hurrah with the 1980 Kansas City Royals. Signed off the waiver wire in late August, Cardenal batted .340 in 53 late-season at-bats and then delivered a pinch-hit in the ninth inning of Game 6 of the World Series.

In spite of his reputation for offbeat behavior, Cardenal remained in baseball as a coach, first with the Cincinnati Reds and then the New York Yankees. He particularly won respect for his knowledge of baserunning and outfield play, his two areas of expertise. Cardenal was a coach with the Yankees during their world championship season of 1996, when he became involved in a crucial play.

With the Yankees holding onto a 1-0 lead in the ninth inning of Game 5, Chipper Jones led off third base and Ryan Klesko led off first base, while John Wetteland faced Luis Polonia. Moments before the at-bat, Cardenal noticed that Paul O’Neill was out of position in right field. Cardenal waved frantically in the direction of O’Neill, telling him to move several steps toward right-center field.

Polonia swatted a Wetteland delivery toward the right-field alley, deep and seemingly with enough distance to reach the warning track. Racing toward the wall at Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium, O’Neill barely caught up with the drive, snaring it in the webbing of his glove. If not for Cardenal’s re-positioning, O’Neill would have had no chance at making the catch.

Cardenal eventually left the Yankees, coached for the Reds and Tampa Bay Rays for a while, and then took a job working in the front office of the Washington Nationals. At the end of the 2009, he announced his retirement from the game. That ended a professional career that spanned 50 years as a player, coach, and front office advisor.

It’s sad when we lose baseball lifers to retirement, especially characters like Cardenal, whose stories and escapades could fill volumes. Whether it was wearing pants so tight-fitting they could cut off his circulation, claiming that crickets kept him up at night, or growing his hair the size of a tumbleweed, José Cardenal made the game a little less routine and a lot more stylish.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame