- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1973 Topps Dave Nelson

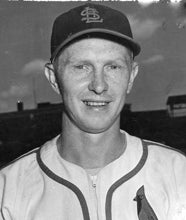

#CardCorner: 1973 Topps Dave Nelson

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

As we move closer and closer toward the holiday season, it’s inevitable to start thinking about the members of the baseball world who have left us this year.

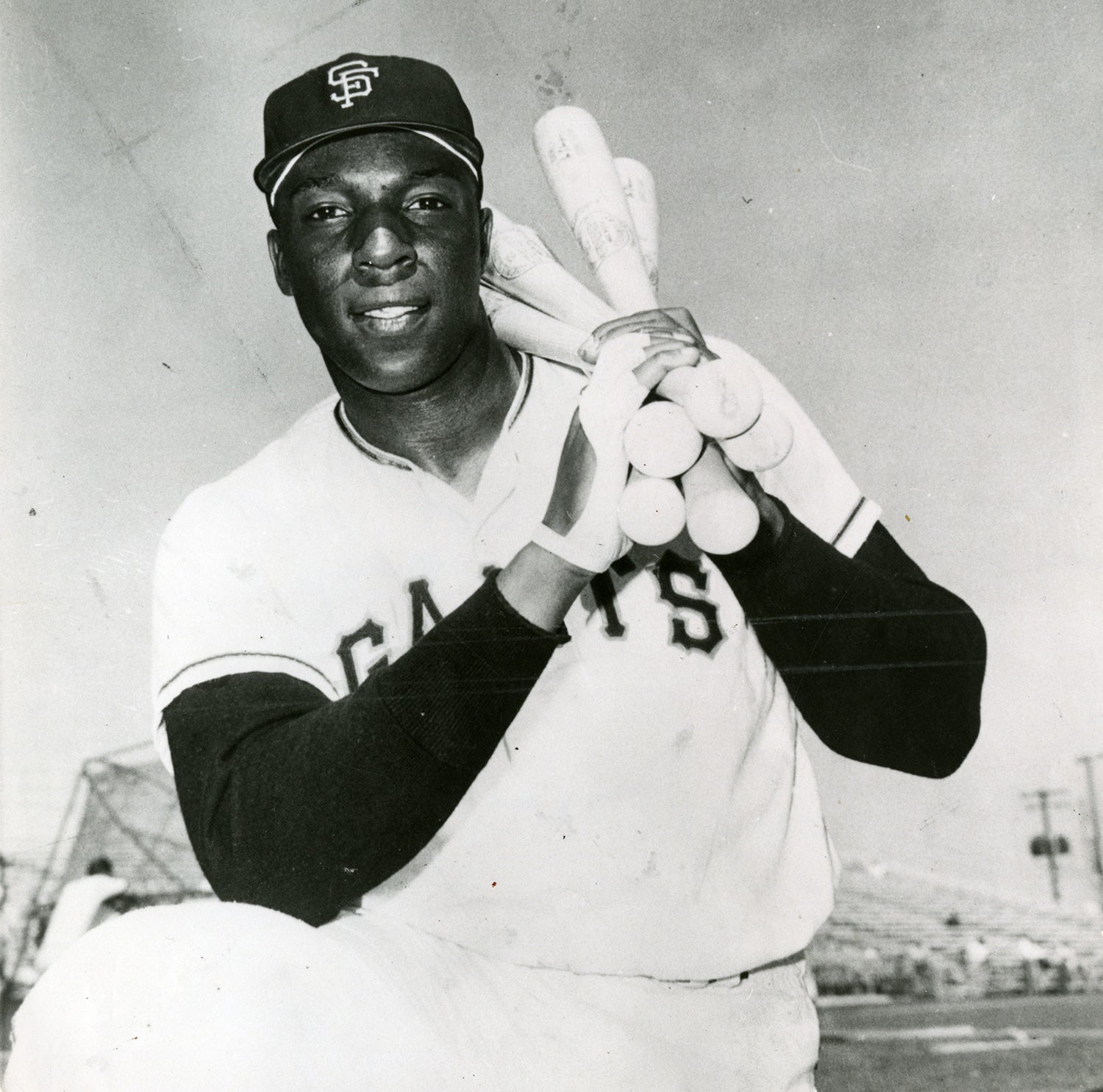

From the ranks of the Hall of Fame, we have lost Willie McCovey, beloved member of the San Francisco Giants and one of the most intimidating hitters of the last 60 years. The year has also been marred by the death of Red Schoendienst, so accomplished as both a player and manager and one of the icons in St. Louis Cardinals history.

There have been others, too. Bob Bailey, Ed Charles, Tito Francona, Oscar Gamble, Bruce Kison, Wally Moon, Marty Pattin and Rusty Staub are among the many departed of 2018, all leaving behind legacies that recall earlier eras in the game’s history.

Bailey, Charles, Gamble, Kison, and Moon have all been profiled in this space. All of them had memorable careers, and all had at least one intriguing card that deserved further exploration. Another man worthy of being added to the list is a lesser known player, but one who still had an impact, both as a standout basestealer and as one of the game’s highly beloved ambassadors.

The late Dave Nelson, or Davey Nelson as he was often called, was one of the fastest runners of the 1970s. His speed was the strength of his game, ahead of his versatility – the latter trait allowing him to play several infield and outfield positions. His most famous achievement involved his speed and came during a game in 1974, when he stole second base, third base and home plate – all in one inning.

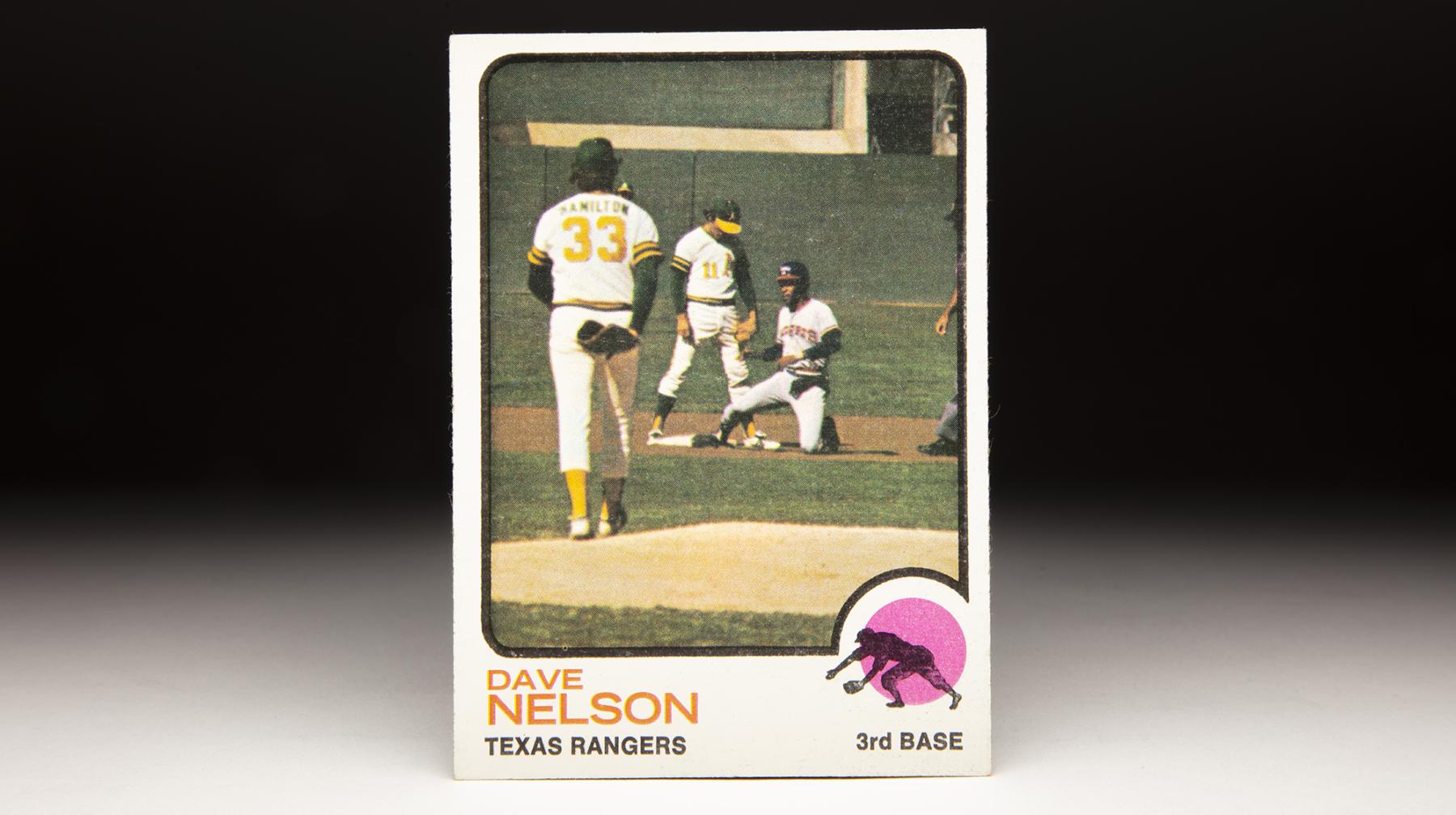

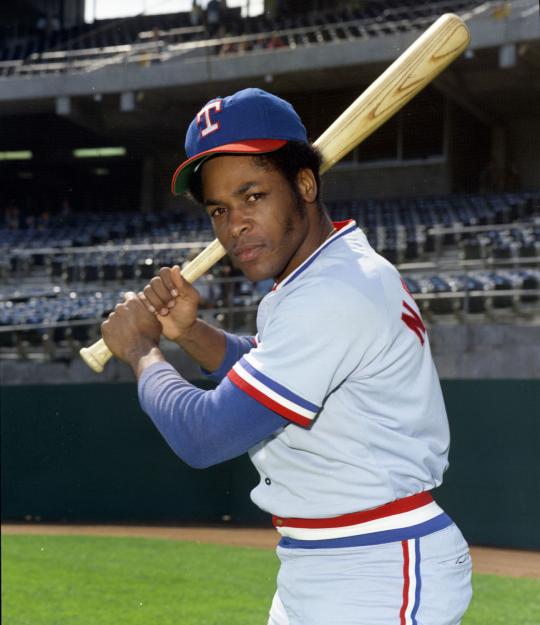

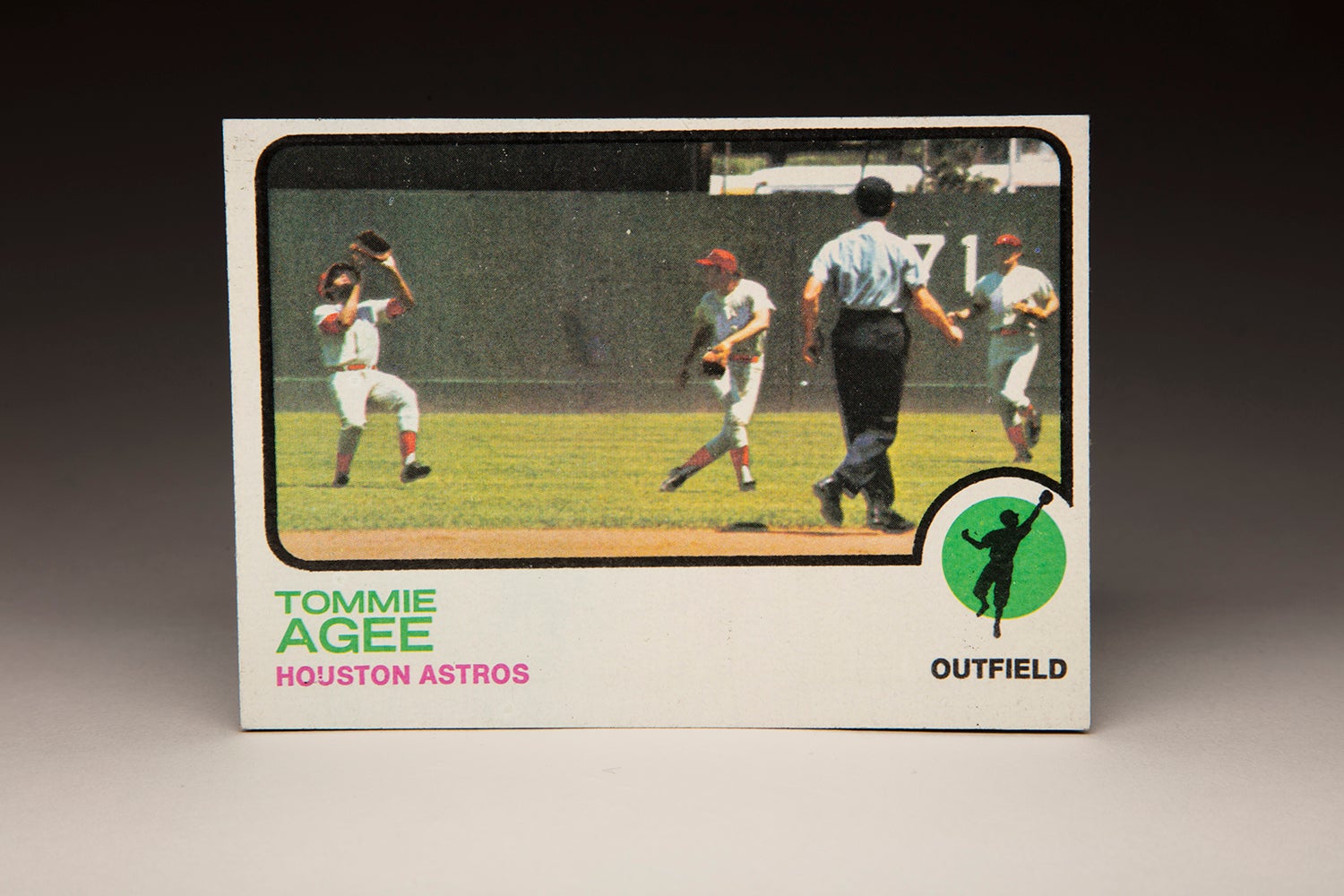

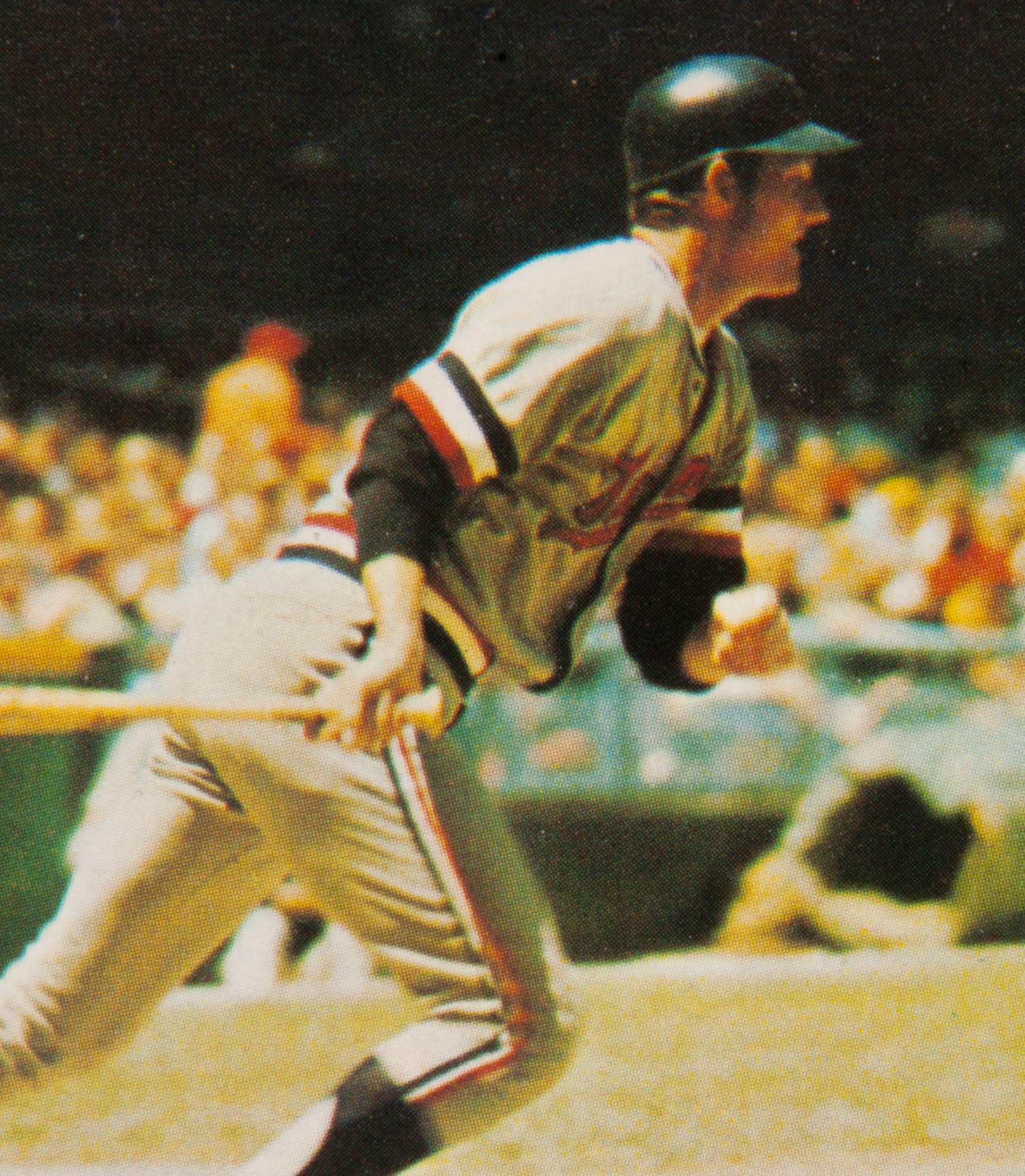

Heading into the 1973 season, Davey Nelson was regarded as one of the game’s most dangerous base stealing threats. He had stolen 51 bases in 1972, despite batting only .226 with a mere .324 on-base percentage. Fittingly, Nelson’s 1973 Topps card shows him stealing one of those bases.

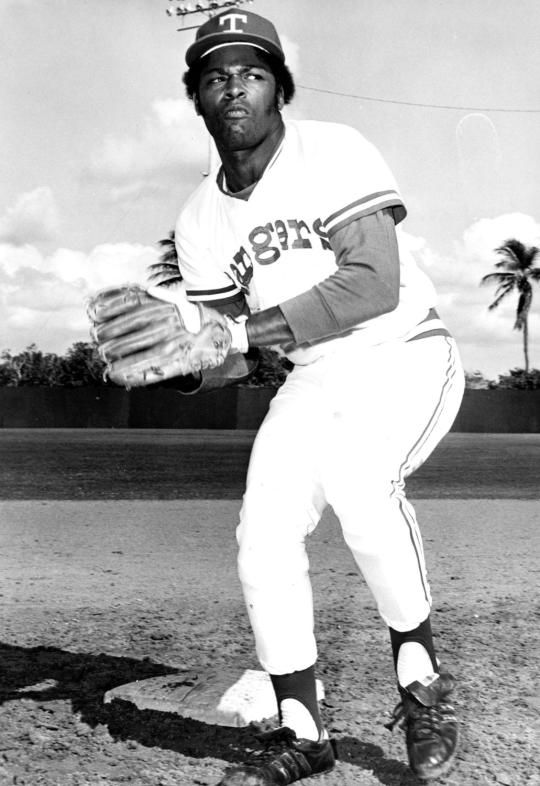

Nelson, wearing the road grays with blue and red trim that the Texas Rangers featured during their first year of existence, is one of three players to make an appearance on the card. The other two are members of the Oakland A’s: Middle infielder Ted Kubiak (No. 11) and left-handed pitcher Dave Hamilton (No. 33). Ironically, both of those players are more prominent on the card than Nelson himself. Hamilton is striking a bit of an odd pose, his back turned from home plate as he wraps his glove around his back. In the meantime, Kubiak has his head down, his eyes focused on Nelson’s right leg.

In trying to figure out when and where the game was played, the Oakland uniforms give us an important clue. The A’s are wearing their all-whites, which they used only for Sunday home games at the time. So the venue must be the Oakland Coliseum. To make our sleuthing a little easier, a check of Baseball-Reference.com shows us that Nelson appeared in only one game at Oakland that summer; it occurred on July 30. Playing in the first game of a doubleheader, Nelson singled twice against Hamilton, the Oakland starter, and stole bases each time. It’s impossible to know which of the stolen bases was captured by Topps, but it’s safe to say that the play happened during that game, which the Rangers won, 4-2.

The Nelson card is typical of what Topps offered in 1973. Anxious to include as many action shots as possible, Topps often presented cards with multiple players, sometimes as many as three or four at a time. At times, it was hard to figure out who the featured player was, particularly when Topps included several players from the same team. And in many cases, the featured player appeared the smallest on the card, as a kneeling Nelson does on this one.

Still, there is something artistic about the Nelson card. Even on this strange canvas, Nelson remains the focal point, the center of interest. Our eyes are drawn toward him because of the other two players. Hamilton is walking toward Nelson, while Kubiak’s eyes are staring right at the kneeling baserunner, hoping that Nelson’s foot will come off the bag. Nelson is the recipient of our attention – as he should be.

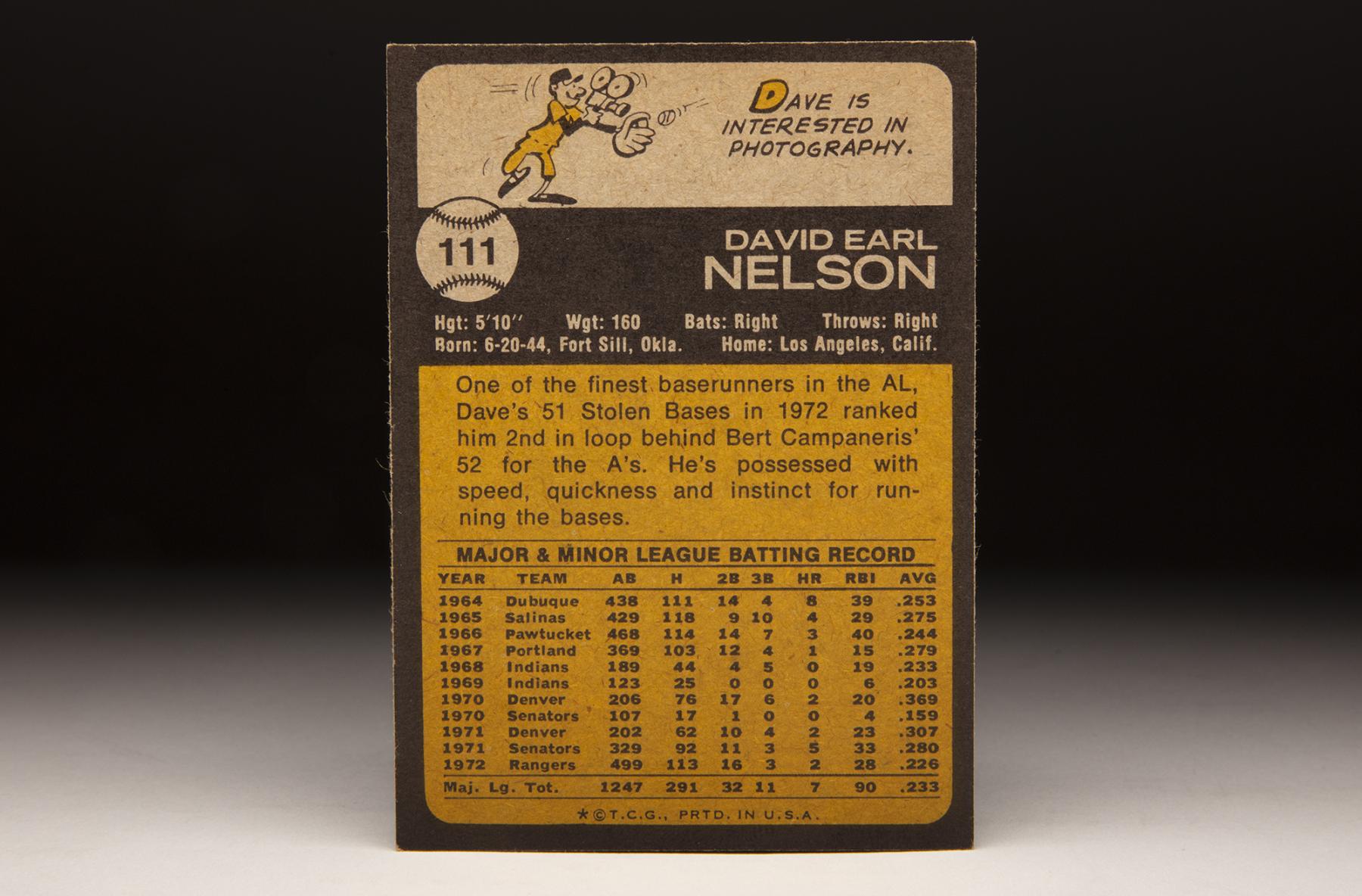

By 1973, Nelson had established a reputation as one of the American League’s most dynamic and aggressive baserunners, but his career began nearly a decade earlier. The Cleveland Indians signed Nelson to his first pro contract prior to the 1964 season and assigned him to Class A Dubuque. He would spent two seasons in Single-A before moving up to Double-A in 1966. Playing for Pawtucket of the Eastern League, he batted only .244 but did draw 70 walks and stole 57 bases. His fielding at second base, with 28 errors in 127 games, represented a concern.

Given his speed and his ability to get on base, the Indians still regarded him as worthy of a promotion to Triple-A Portland. He actually hit better there, lifting his batting average to .279 and remaining a force on the basepaths. He also played better defensively, cutting down his errors and improving his range.

In the spring of 1968, Nelson came to Spring Training and so impressed the Indians that he was named the “most outstanding player in Spring Training” by the team’s writers and broadcasters. More importantly, he made the Indians’ roster as a backup to second baseman Vern Fuller and shortstop Larry Brown. On Opening Day, Nelson made his debut while his parents watched from the box seats. Playing mostly as a bench player, the fleet rookie batted only .233 and struggled to reach base. But when he did, he made an impact, stealing 23 bases.

Nelson returned to the Indians in a similar role in 1969, but his hitting bottomed out. His batting average fell to nearly .200, and with fewer opportunities to run, he stole only four bases. Nelson’s performance so disappointed the Indians that they traded him that winter, sending him to the Washington Senators as part of a package for pitchers Dennis Higgins and Barry Moore.

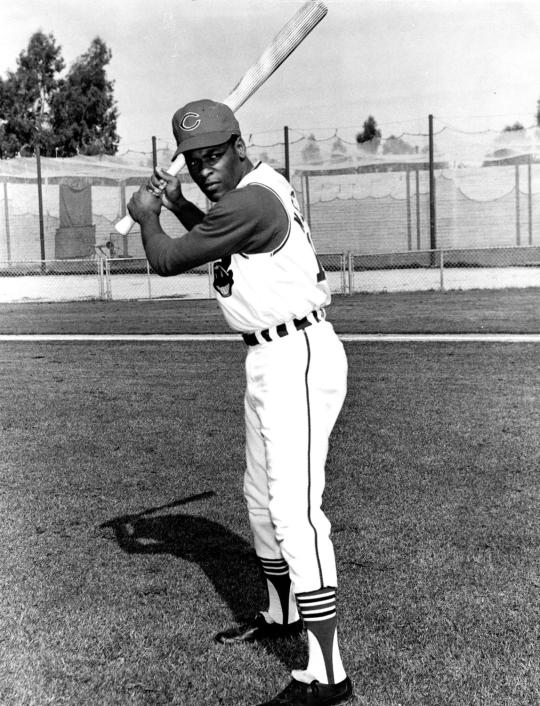

Nelson hoped that a change of scenery would boost his career, but the first half of the season turned into disappointment. Nelson struggled badly, his batting average falling to .127 in early June, when the Senators optioned him out to Triple-A Denver. Afforded the chance to play every day in the Mile High City, Nelson hit a robust .369 with 20 stolen bases.

The Senators brought him back in September and gave him a chance to play regularly at second base, but his hitting improved only slightly. That left his status in doubt for the 1971 season.

During the spring of ’71, Senators manager Ted Williams made a change with Nelson. Williams converted him to third base, where he felt that his defensive skills would be better suited. Nelson was hardly the classic corner man; in fact, he had never hit a home run during his first three major league seasons. But the move to third base seemed to help his stamina – and his hitting.

After starting the season at Denver, Nelson returned to Washington in June. Williams worked with him on his hitting, encouraging him to hit with more power. Nelson responded by hitting five home runs. Nelson showed major improvement in another way, too. Serving mostly as a No. 2 hitter, but occasionally batting leadoff, Nelson lifted his batting average to .280.

Nelson became one of the more stable elements of a franchise in upheaval. The 1971 season marked the final year of the Senators in Washington. As it became evident that owner Bob Short was intent on moving the franchise, the fans expressed their displeasure, culminating in a riot on the final day of the regular season. Somehow, Nelson remained above the fray, playing well, and making the offseason move to Texas along with the rest of the franchise.

In 1972, Nelson’s batting average fell off to .226, but he embraced Williams’ philosophy of patience, drawing a career-best 67 walks. He put the walks to good use, stealing a league-leading 48 bases. At one point, Nelson drew a favorable comparison to a legendary basestealer from an earlier era.

“Nelson studies the pitchers… And for the first two or three steps, he has tremendous explosion,” said Don Drysdale, now a Rangers broadcaster, in an interview with the Associated Press. “That’s what Maury [Wills] had in his prime. He didn’t have blazing speed, but he could get into high gear.”

Nelson also received praise from his Hall of Fame manager. “He shows excellent judgment,” Ted Williams told the AP. “He reminds me a lot of Luis Aparicio in his prime.”

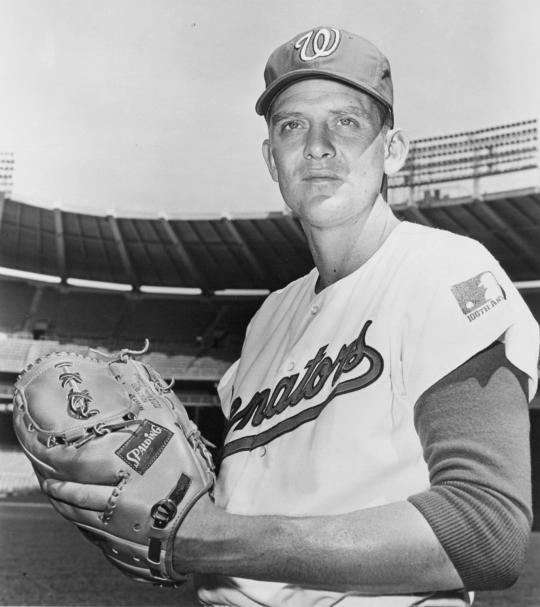

While Nelson’s speed dominated his game in 1972, he would broaden his skill set in 1973. A new manager, Whitey Herzog, took over the team and switched Nelson back to second base, but he only played better. In fact, he earned the first and only All-Star Game selection of his career. For the season, Nelson hit a career-high .286 while also reaching high-water marks in home runs and RBI.

Toward the tail end of the season, the Rangers fired Herzog, eventually replacing him with Billy Martin. Nelson became a Martin favorite, admired for his hustle and his willingness to play with obvious pain. Martin likened Nelson to Jackie Robinson, praising him for his daring baserunning style and aggressive approach to playing.

Across the game, Nelson gained admiration for his gregarious personality. As Red Smith wrote for The New York Times, “Dave Nelson’s outgoing charm conceals one of the most larcenous natures in the American League.” Nelson’s “larceny” had to do with his ability to steal bases, a total of 94 over the last two seasons.

The Rangers hoped for more of the same in 1974. But at one point during Spring Training, it appeared that Nelson might be changing teams. Rumors circulated about the New York Yankees having strong interest in Nelson, whom they regarded as Horace Clarke’s successor at second base. One rumor had the Yankees sending a left-handed pitcher, either Fritz Peterson or Sam McDowell, to the Rangers for Nelson.

As hard as the Yankees tried to entice the Rangers, Texas turned down multiple offers for Nelson. Unfortunately, injuries would soon alter his season in a different way. On May 11, Nelson collided with teammate Lenny Randle, resulting in a broken nose. Then came injuries to his ankle and knee in mid-July, as he attempted to turn a double play. The various injuries, including a torn ligament in his ankle, limited him to 121 games and took a toll on his hitting and speed. He batted .236 and stole only 25 bases, his lowest total since 1971.

Nelson reported to Spring Training in 1975 determined to make a full recovery from his ankle injury. He played well in exhibition games, continuing to impress Martin with his grit and toughness. But the pain in his ankle returned early in the season. An examination showed the development of a bone spur on his ankle. Doctor prescribed surgery, which put him on the shelf until the middle of August.

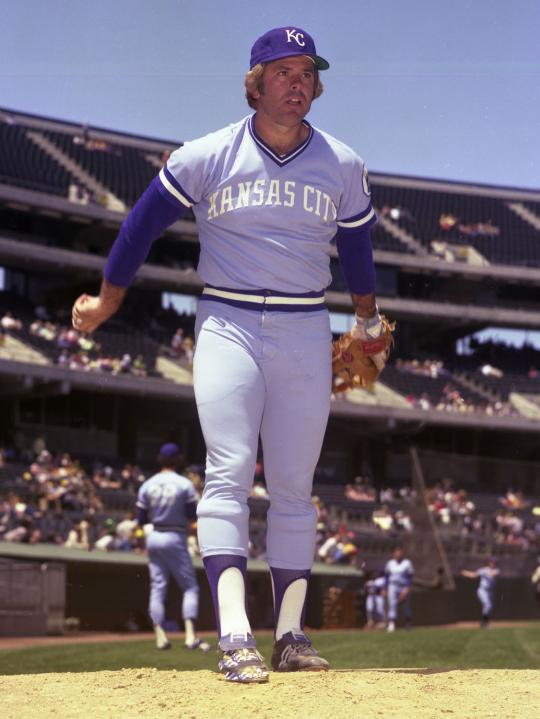

The cascade of injuries resulted in a lost season for Nelson. He played in only 28 games, batting a mere .213. His range in the field was also affected. The poor season, coupled with his advancing age (he was now 31), sealed Nelson’s fate with the Rangers. That winter, they traded him to the Kansas City Royals as part of a package for veteran right-hander Nelson Briles.

In joining the Royals, Nelson knew that his days as an everyday player were over. The Royals already had Frank White and Cookie Rojas at second base, and a young George Brett manning third. Nelson played the role of utility man, filling in at second, first base, and as a DH, all while stealing 15 bases off the bench.

While Nelson saw his playing time cut, he also saw a benefit with the Royals, who won their first division title in 1976. That gave Nelson his first shot at the postseason; he would appear in two games against the Yankees, who defeated the Royals in a dramatically played five-game series.

The 1977 season resulted in an even more reduced role for Nelson. He played in only 27 games, a career low, and stole only one base. The Royals brought Nelson back for Spring Training in 1978, but he couldn’t crack the Royals’ deep and improving roster. On April 1, the Royals gave Nelson his unconditional release. Rather than pursue opportunities in Japan or Mexico, the 33-year-old opted for retirement.

While his baseball skills had declined, Nelson still had something to offer the game. In 1980, he did some coaching at Texas Christian University before returning to the major leagues as a coach with the Chicago White Sox. He later did some work for the Oakland A’s and Montreal Expos, sandwiched around a brief broadcasting tenure with the Chicago Cubs. Then came a stint with the Indians, his original team, first as a coach and then as a broadcaster.

In 2001, Nelson began a long association with the Milwaukee Brewers. He became the team’s first base coach, worked the broadcast booth for a spell, and then moved on to the front office as the director of alumni relations. With his amiable personality, Nelson became a natural as the head of the Brewers’ alumni group, fostering strong relationships with many of the team’s retired players. Nelson was one of those people who could meet a stranger for the first time – and make a friend for life.

As much as Nelson loved baseball, he also cared about folks outside of the sport. He took on a number of charitable causes, including the founding of a boarding house for South African children left orphaned by the AIDS epidemic. To friends and colleagues, that kind of selfless involvement was typical of Nelson.

Nelson was continuing to work for the Brewers when he noticed some difficulty swallowing in August of 2017. He paid a visit to the doctor, who gave him a grim prognosis: Stage 4 liver cancer that had already spread to his esophagus. Nelson underwent treatment, regained his sense of taste and seemed to be doing well, but then the cancer took hold again. In April of 2018, he lost the battle, passing away at the age of 73.

Nelson’s death stirred reactions across the baseball globe. Perhaps the words of Rangers broadcaster Tom Grieve, a onetime teammate, best described Nelson. “What a great guy,” Grieve told Adam McCalvy of MLB.com. “I've known Dave since I first began playing baseball. My first Major League Spring Training in Pompano Beach, [Fla.], the first person I met was Dave Nelson. He had a red Corvette, and he asked me out to dinner. “He was one of those people you could say that everybody liked him.”

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame