- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1973 Topps Gene Clines

#CardCorner: 1973 Topps Gene Clines

One of the joys of Hall of Fame Weekend is the sheer presence of so many former big league players at one time. Not only are 50-plus Hall of Famers expected to be in town for the weekend’s Induction Ceremony in Cooperstown, but there are also a number of other retired players who are scheduled to be in town at some point.

Official Hall of Fame Apparel

Proceeds from online store purchases help support our mission to preserve baseball history. Thank you!

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Some are here as invited guests of our six new inductees, while others have come to participate in autograph signings on Main and Pioneer streets. In some cases, the players have come here for both of the reasons. All of this contributes to what is essentially a festival of baseball and its history. Even for fans who have attended an All-Star Game or a World Series, there is nothing quite like the atmosphere that comes with Hall of Fame Weekend.

One of the many retired players who was often in Cooperstown for the big event was Gene Clines, a former player and a longtime coach. Clines became one of the game’s most respected coaches, particularly when it came to the art of hitting. That’s just one of many chapters in the fascinating baseball life of Gene Clines.

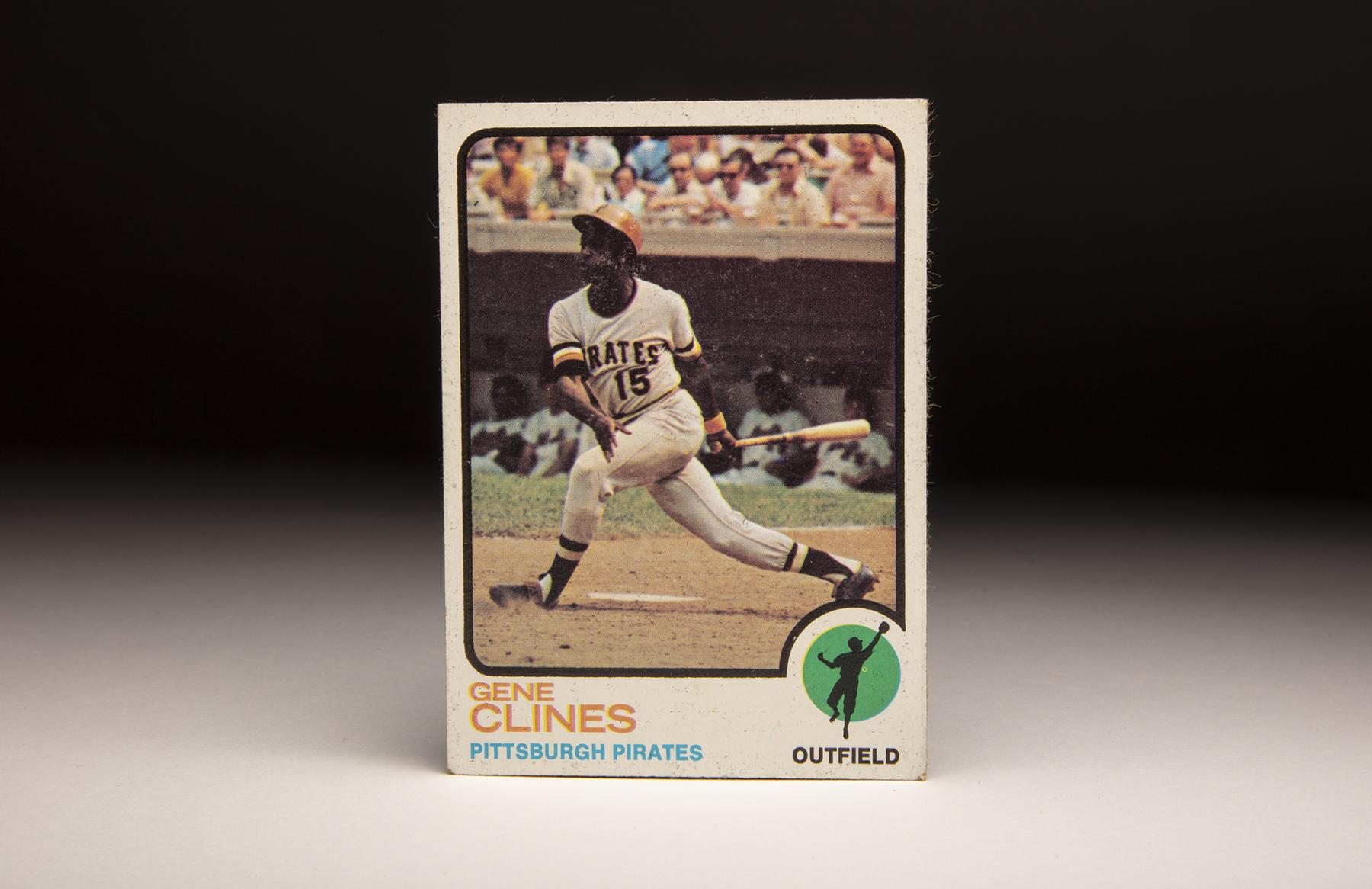

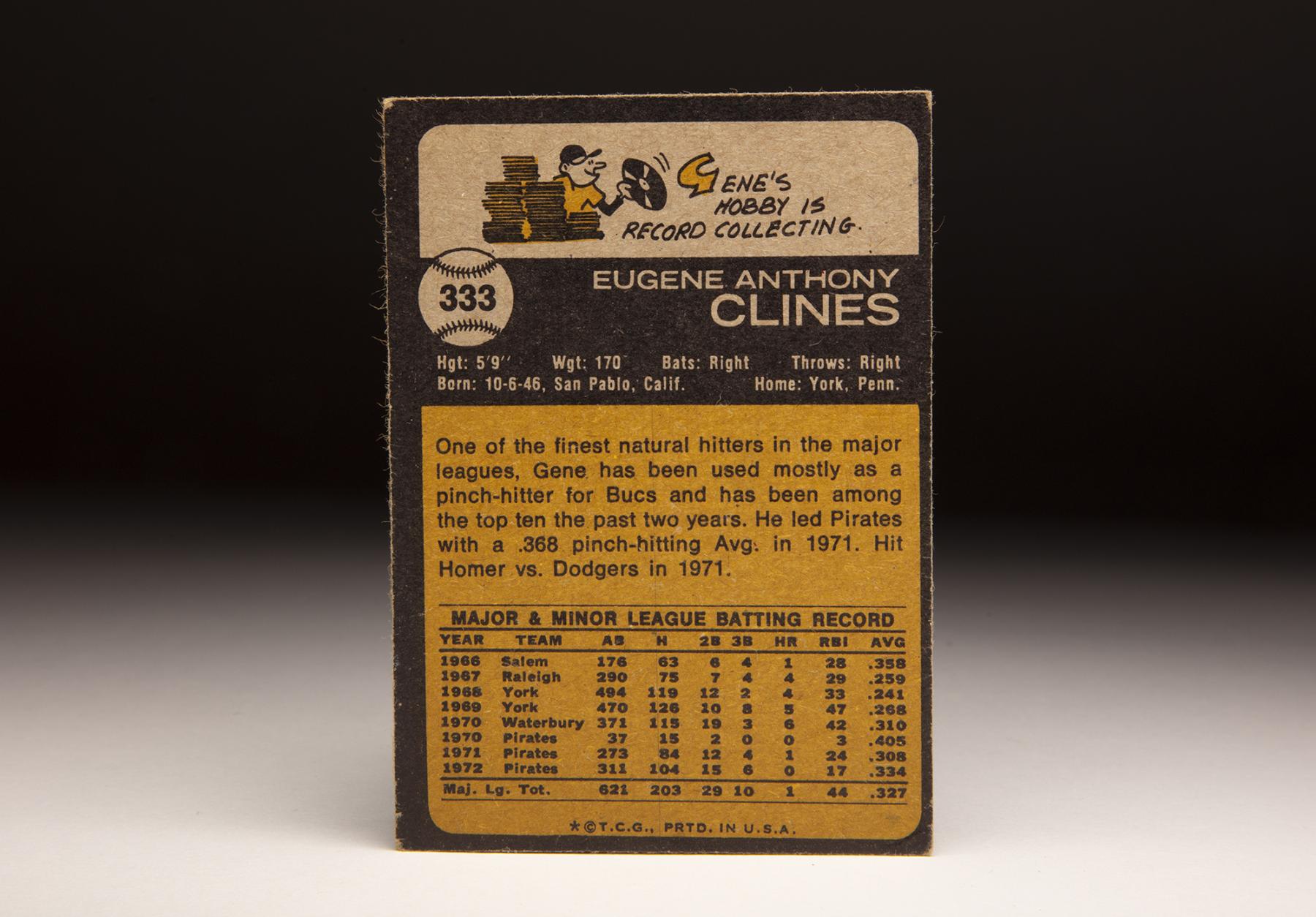

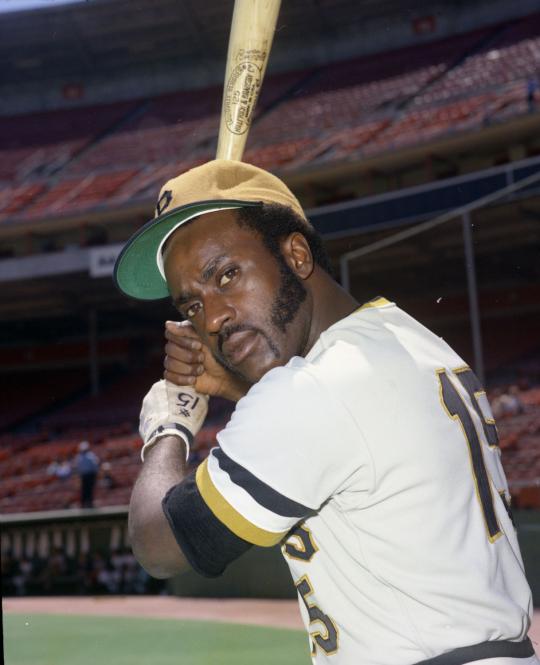

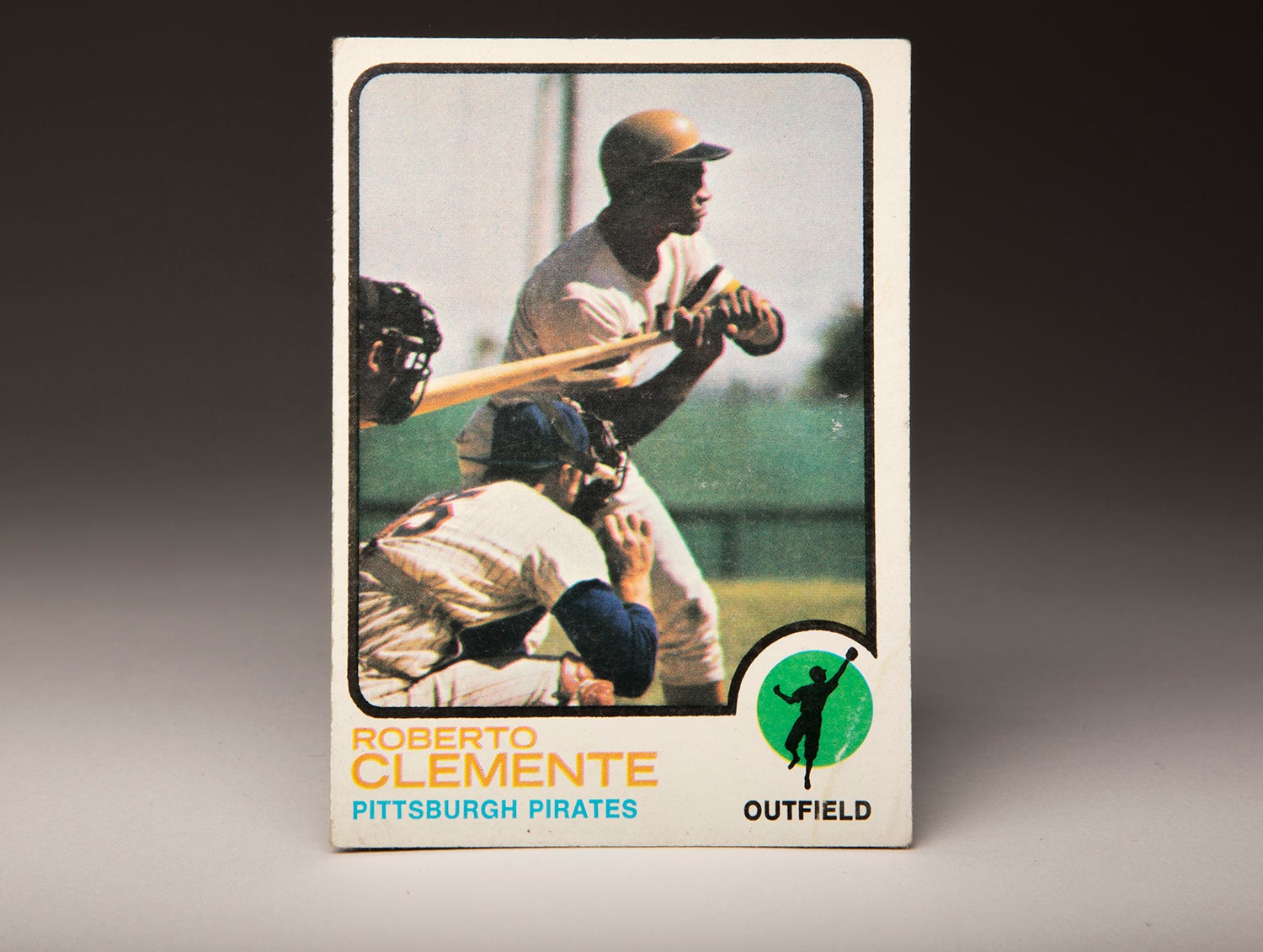

Of all the Clines cards produced by Topps, my favorite is the card from 1973. It’s one of the better action shots in the set. Taken at Shea Stadium, as so many of the Topps photos were back in the 1970s, the photo gives us a glimpse into the New York Mets’ dugout, but the background is not clear enough for us to make out any of the numbers or the faces of the Mets’ players. Yet it does give us a pretty good look at Clines and his 5-foot-9-inch frame.

The photograph shows Clines near the end of his swing. Having just released his bottom hand, which is now fully open, Clines is still holding onto the bat with his top hand. I particularly like the way the card shows his legs in motion. His back leg is fully extended and seems to be supporting most of his weight, while his front foot front has landed rather awkwardly, tipped to its left side while it kicks up some dirt from the home plate area.

This is not exactly the balanced follow-through that a hitter desires, but it does give us a glimpse into the complexity of a completed swing. There is just so much going on, between the hands, arms, and legs; no wonder hitting a baseball is the hardest feat in modern team sports.

As a young player in the Pittsburgh Pirates’ system, Clines showed talent with a bat in his hand – and on the bases. He had little power, but could hit for average and run like “The Flash.” He first drew the Pirates’ attention while he was in high school, where he was not only a standout ballplayer but a champion high jumper. Taken in the sixth round of the 1966 MLB Draft, Clines received his first professional assignment to Salem of the Appalachian League, where he promptly batted .358 with an .897 OPS. He also stole 15 bases in 18 attempts.

In 1967, the Pirates bumped Clines up to full-season Single-A ball. The higher level of competition proved demanding; Clines batted only .259 with a mere 15 walks against 64 strikeouts. Despite those struggles, the Pirates challenged Clines by promoting him again in 1968, this time to the Double-A Eastern League. Clines again struggled, hitting only .241 with 30 walks against 82 strikeouts.

In 1969, the Pirates decided to have Clines repeat Double-A York – with far better results. He batted a more respectable .268, drew 48 walks, and fully utilized his baserunning skills by stealing 63 bases. Given his outright speed, it was no surprise that Clines earned the nickname of “Roadrunner.”

In 1970, the Pirates moved their Double-A affiliate to Waterbury, where Clines played his third consecutive season in the Eastern League. This time around, Clines mastered Double-A pitching, to the point that the Pirates brought him to Pittsburgh in mid-June. Clines would later return to Double-A, but then received a callback from the Pirates in August. Used as a utility outfielder who played left, center, and right field, Clines batted .405 in 37 sporadic at-bats. Although the sample size was small, the Pirates took notice. In 1971, they included him on their Opening Day roster.

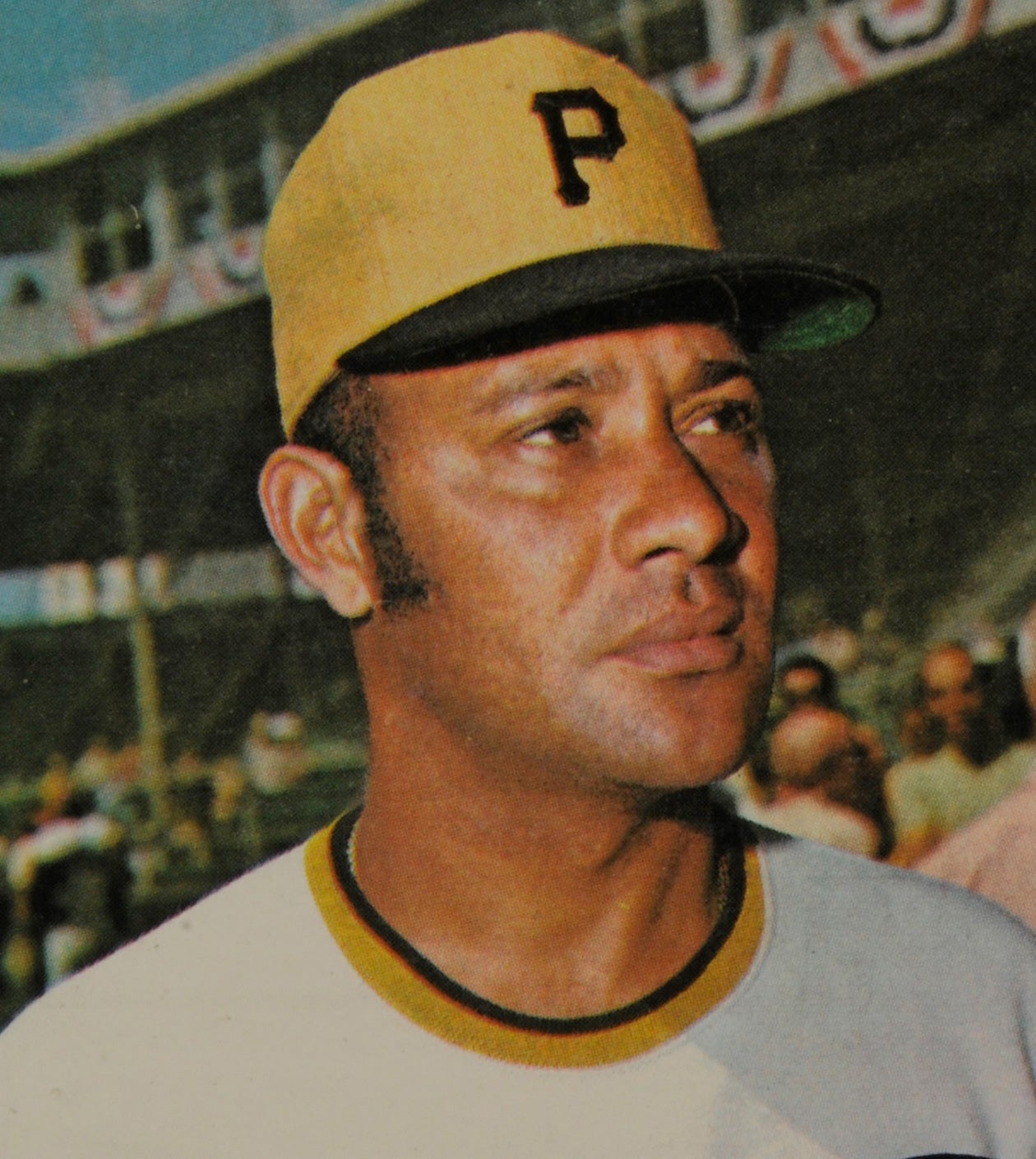

The Pirates gave Clines a substantial role on the ’71 team. Not only did they use him as a backup to Willie Stargell in left field and Roberto Clemente in right, but they gave him significant playing time as the starting center fielder against left-handed pitching. Prospering in a time-sharing arrangement with Al Oliver, Clines batted .308, reached base 36 percent of the time and stole 15 bases. He also took part in a sometimes-overlooked part of baseball history. On Sept. 1, Clines started in center field and batted second, as the Pirates assembled the first all-black lineup in major league history.

While players like Clemente, Stargell, Dock Ellis, and Steve Blass garnered most of the headlines, Clines became part of a second tier of Pirate support players who did their part in pushing the team to an Eastern Division title. In the NLCS against San Francisco, Clines picked up one hit in three at-bats, as the Bucs won the series, three games to one.

The World Series brought Clines even more playing time; he came to bat 11 times and appeared in three games. While he collected only one hit, the Pirates as a team pulled off one of the most monumental upsets in October history, stunning the favored Baltimore Orioles in seven grueling games.

With a World Series ring now in his collection, Clines did not rest on his laurels. In 1972, he assembled his best season, while playing for new manager Bill Virdon, who had replaced the retiring Danny Murtaugh. Platooning in left field with another key role player, Vic Davalillo, Clines batted .334 average in 311 at-bats, and even earned some support in National League MVP balloting. Some within the Pirates’ organization felt that Clines was on the verge of becoming a star.

After a strong start in 1973, Virdon eventually installed Clines as the Pirates’ everyday right fielder. He replaced a struggling Manny Sanguillen, who had done his best to succeed Clemente, who died in a wintertime plane crash. Soon after moving into right field, Clines tore ligaments in his right ankle, forcing him to the sidelines. When he returned to action, he struggled at the plate, perhaps still bothered by the after-effects of the injury.

By season’s end, Clines was batting a mediocre .263, an average that might have been more acceptable if Clines hit with power. Once again, Clines had become a victim of the numbers game in the crowded Pirates’ outfield, this time because of the presence of two young sluggers, Dave Parker and Richie Zisk. In response, Clines complained regularly to Pirates management about his sporadic playing time.

That winter, a series of trade rumors circulated around Clines, but he remained with the Pirates as the team reported for Spring Training in 1974. That summer, Clines would experience the most difficult season of his career. Off the field, he dealt with the loss of his father. On the field, Clines batted a career-low .225. A wave of young outfielders coming up through the Bucs’ minor league system – headlined by Parker and Zisk – forced Clines to the sidelines more and more.

Given the glut of outfield talent in Pittsburgh, a trade made sense. That winter, the Bucs dealt Clines to the New York Mets for backup catcher Duffy Dyer. Clines could hardly contain his glee.

“I’m happy to be gone from the Pirates,” Clines told the New York Times. “They made up their minds a long time ago that I didn’t fit into their plans, and there was never a thing I could do to change their minds.”

Clines hoped that the Mets, a team with a thinner outfield than the Pirates, would give him more playing. It didn’t happen. Clines struggled at the plate, limiting him to 205 at-bats. For the season, he batted a meager .227. After the season, the Mets moved on, dealing Clines to the Texas Rangers for switch-hitting outfielder Joe Lovitto. The Rangers gave Clines more playing time than the Mets or Pirates had ever done, but the results proved to be mixed. Clines batted .276, but drew only 16 walks and failed to hit a home run.

Dissatisfied with Clines lack of production and inability to reach base more often, the Rangers traded him to the Chicago Cubs for left-handed reliever Darold Knowles. In 1977, Clines settled into a role as a utility outfielder, batting .293. The following summer, he slumped to .258. Clines again complained about a lack of game action, but manager Herman Franks explained that he considered Clines the “heart of the club.”

In an interview with the Sporting News, Clines replied to the curious assessment with a classic response: “If I’m the heart,” said Clines, “then his heart is having a seizure.”

Early in the 1979 season, the Cubs placed Clines on waivers, effectively ending a career that had once seemed so promising. Some of the stardom that eluded Clines as a player would occur during a long career in coaching.

After being released by the Cubs, Clines remained with the organization as a coach. He then joined the Houston Astros as a minor league hitting instructor before earning a promotion to the major league staff in 1988. Clines later worked as a coach for the Seattle Mariners and Milwaukee Brewers.

After the ‘96 season, the Giants named Clines their major league hitting instructor under manager Dusty Baker. While with the Giants, Clines developed a reputation as one of the game‘s finest hitting coaches. His skills included the ability to strike a positive chord with the team’s best player, Barry Bonds. Clines also drew considerable praise from many of the Giants’ veteran hitters, including Jeff Kent, who raved about his coach’s manner and approach.

Clines’ work as a hitting coach found its roots during his days as a player, particularly with the Pirates. That’s where he observed the batting techniques of his teammates.

“Dave Cash, Willie Stargell, Roberto Clemente, we watched each other so much we knew each other’s swings,” Clines told Henry Schulman of the San Francisco Chronicle. “If we were having problems in certain situations, we kind of policed ourselves.”

In 2003, Clines left the Giants when Baker received an offer to manage the Cubs. Clines joined Baker in Chicago, giving him a chance to coach in the same city in which he had played. Five years later, Clines joined the Los Angeles Dodgers as their minor league hitting coordinator. After three seasons of on-field work, the Dodgers promoted him to a position as senior advisor of player development, which he held before rejoining the Giants as a special assistant.

Despite being so highly regarded along the way, Clines has never quite achieved his dream job of managing a major league team.

That’s unfortunate, given Clines’ intelligence, his understanding of hitting, his communication skills and his ability to relate to players of today. For whatever the reason, Clines never received the chance to lead his own team. It’s a stiff reminder that there are only 30 major league managerial jobs available at one time.

In the case of Clines, who passed away on Jan. 27, 2022, it should not diminish what has been a fine and lengthy career as a baseball lifer. It’s a career that included a World Series ring, a chance to play with legends like Clemente and Stargell, a long run as a wise old batting coach, and untold respect from so many he has taught over the years.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame