- Home

- Our Stories

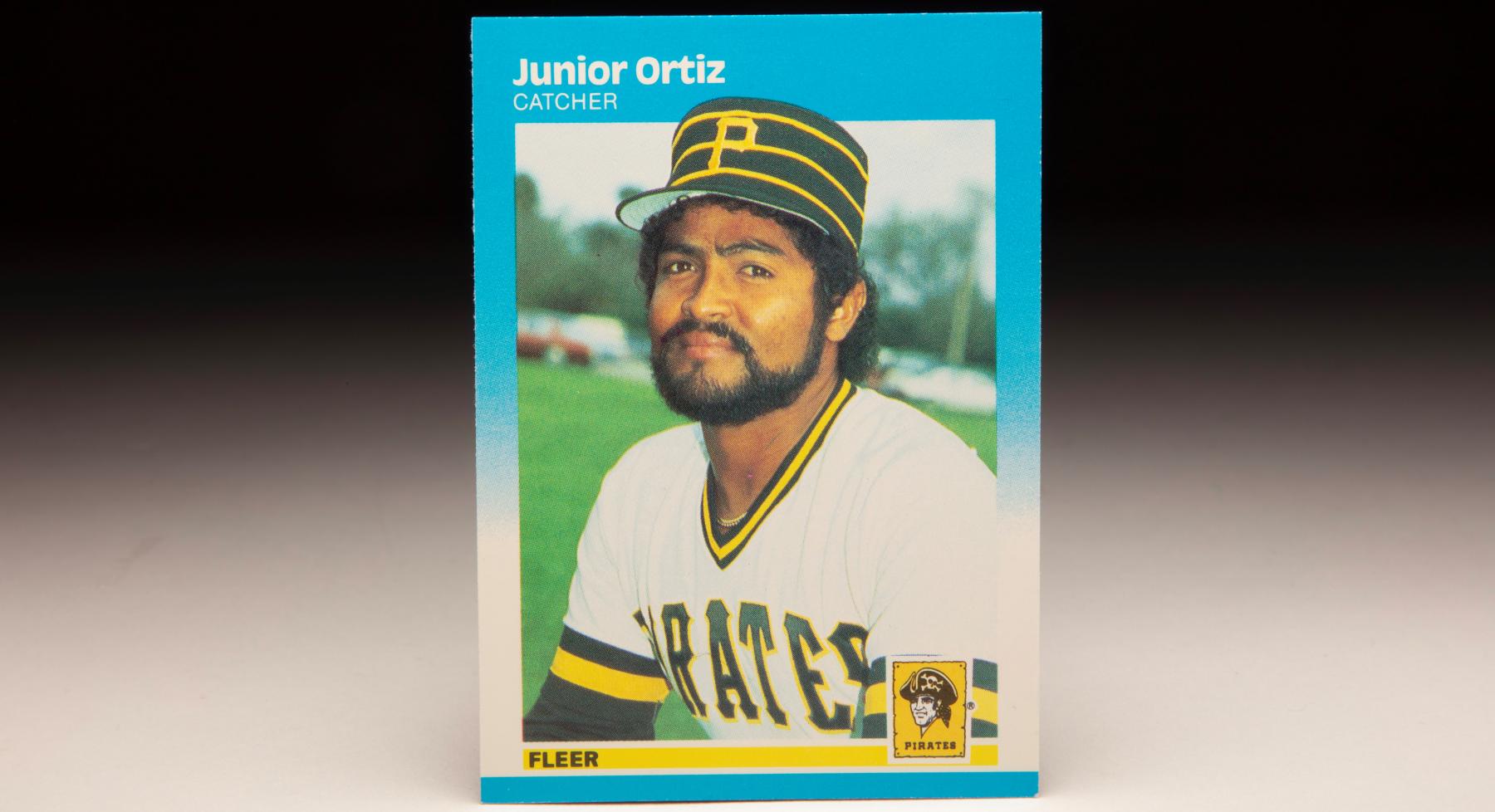

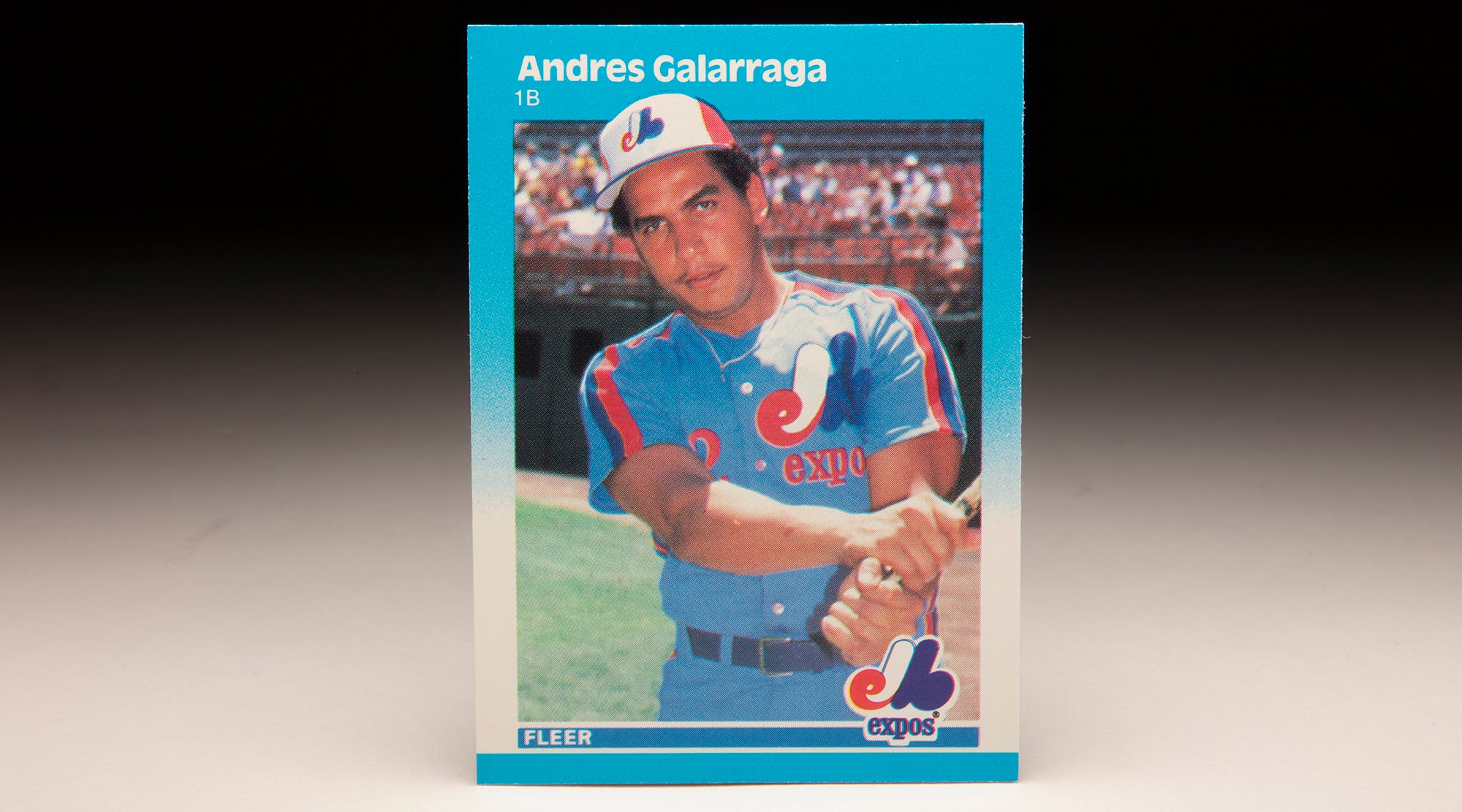

- #CardCorner: 1987 Fleer Junior Ortiz

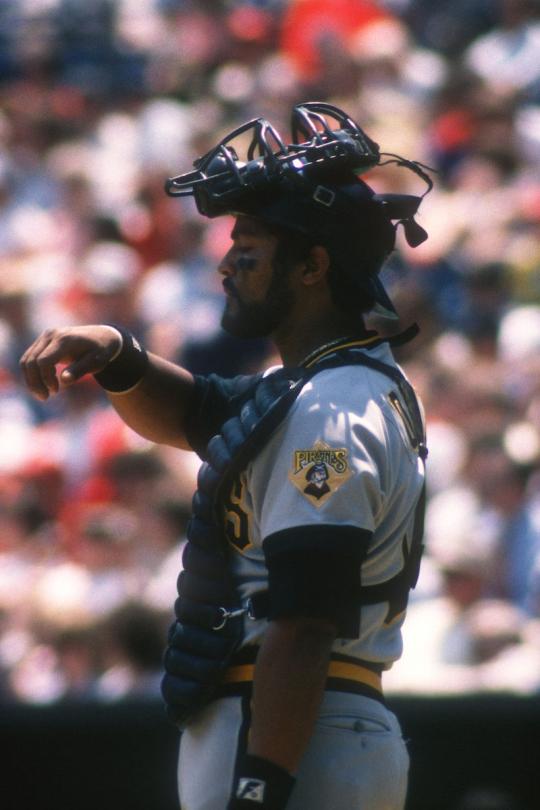

#CardCorner: 1987 Fleer Junior Ortiz

In the year’s prior to the creativity driven by the internet, conformity ruled in big league baseball. And uniform numbers were no exception.

High numbers were to be avoided. Pitchers rarely wore single digits. And few wanted to be associated with a zero.

Al Oliver changed all that in 1978 with the Texas Rangers. George Scott followed with the Royals a year later. But when Pirates catcher Junior Ortiz donned No. 0 in 1989, it was still an oddity throughout the game.

Two years later, Ortiz became the first player in World Series history with zero on his uniform. His play helped the Twins win the Fall Classic and became a highlight of a 13-year big league career as a respected reserve catcher.

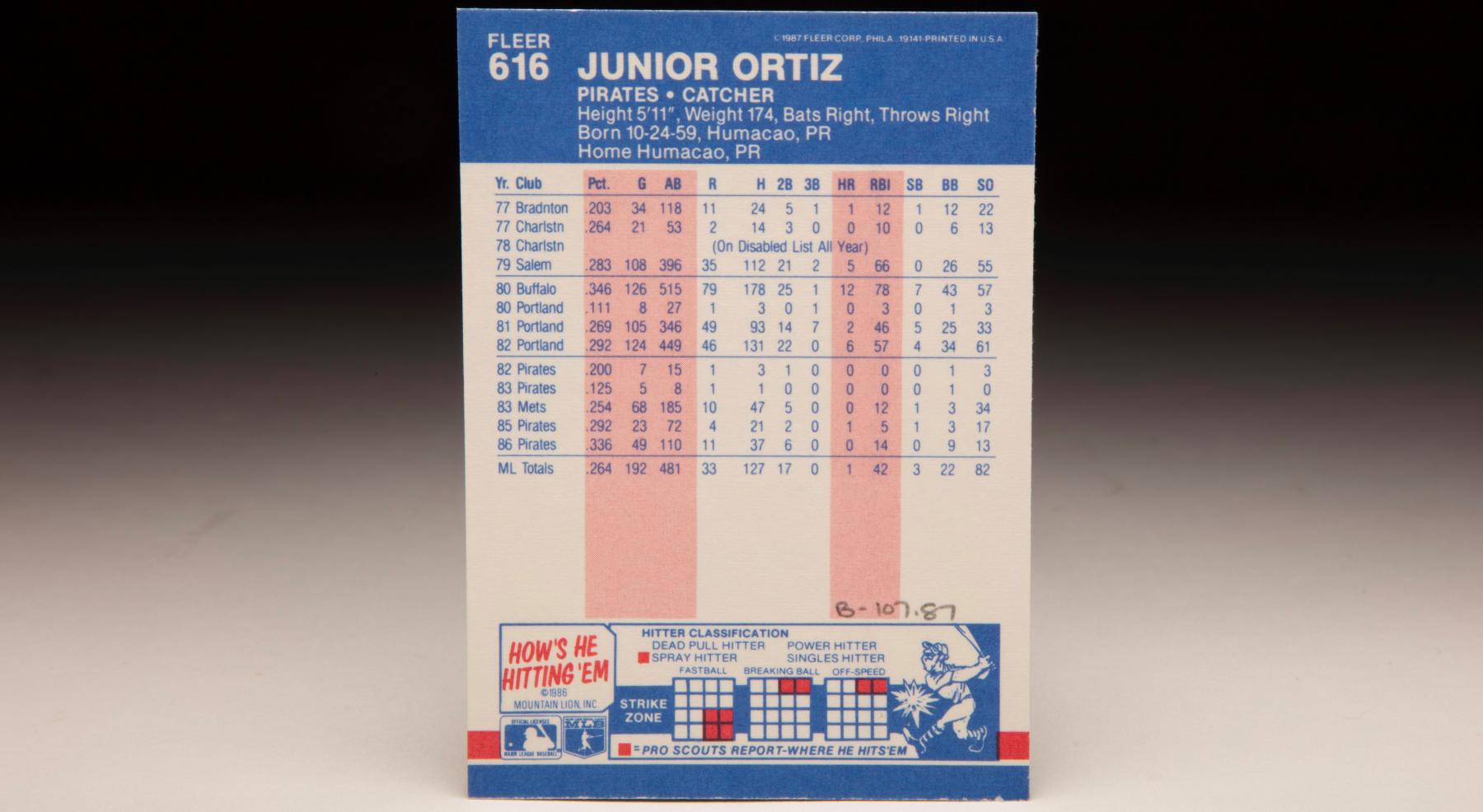

Born Oct. 24, 1959, in Humacao, Puerto Rico, Ortiz signed with the Pirates as an amateur free agent on Jan. 18, 1977. Future All-Star catcher Tony Peña was a step ahead of Ortiz in Pittsburgh minor league system, but Ortiz steadily moved up the chain: Playing Rookie and Class A ball in 1977, returning to Class A Charleston in 1978 and then finding his stride as a 19 year old at Class A Salem in 1979 – hitting .283 with five homers and 66 RBI in 108 games while showing off his powerful right arm.

In 1980, Ortiz starred at the plate for Double-A Buffalo – the same place where Peña hit 34 home runs the year before. In 126 games for the Bisons in 1980, Ortiz hit .346 with 79 runs scored, 12 homers and 78 RBI, earning a spot on the Eastern League All-Star team. He was rewarded with a promotion to Triple-A Portland at the tail end of the season and an invitation to Pittsburgh’s big league Spring Training camp in 1981.

Ortiz began the ’81 campaign with Portland and spent the whole year with the Beavers, hitting .269 with two homers and 46 RBI. But with Peña now in the big leagues and on his way to becoming a star, the Pirates had no room for Ortiz. He returned to Portland in 1982 and hit .292 with 22 doubles and 57 RBI in 124 games before being called up to the big leagues in September, where he had three hits in 15 at-bats over seven games.

Now out of minor league options – as was another young Pirates catcher, Brian Harper – Ortiz was caught in a numbers crunch.

“I’d like to solve the problem before we go to Spring Training,” Pirates general manager Harding Peterson told the Associated Press in December of 1982.

But despite the Mets showing interest in acquiring Ortiz, Peterson made no move. The Pirates opened the season with five catchers on the roster: Peña, Ortiz, Harper, Steve Nicosia and Gene Tenace. Manager Chuck Tanner juggled the lineup by using Harper in the outfield and Tenace mostly as a pinch hitter. But with the durable Peña playing almost every day, little time was left for Ortiz – who played in only two games before June 1.

On June 14, the Pirates and the Mets finally consummated a deal that had been discussed for months, with Pittsburgh sending Ortiz and minor league pitcher Arthur Ray to New York for outfielder Marvell Wynne and pitcher Steve Senteney.

“I know I can play every day and be a regular catcher,” Ortiz told United Press International. “I wanted to come to New York because I have family in New York, I have an aunt and uncle in Brooklyn.

“Everyone knows about my arm. The league knows my arm and I think the league respects my arm.”

Many executives – including Peterson – thought the Mets had solved their catching issues for years to come.

“The Mets got a catcher they desperately need,” said Peterson, “and Ortiz, No. 3 with the Pirates, will be a top catcher for 10 or 12 years.”

The Mets immediately made Ortiz their starting catcher, while Wynne moved into the Pirates lineup as their center fielder. But while Wynne scored 66 runs over 103 games and staked his claim to a starting job in 1984, Ortiz hit .254 but with little power (slugging .281) over 68 contests.

Then in 1984, Ortiz lost the starting job to youngster Mike Fitzgerald and totaled just 98 plate appearances in 40 games, hitting .198. The Mets dropped Ortiz from the 40-man roster – and the Pirates claimed him in the Rule 5 Draft.

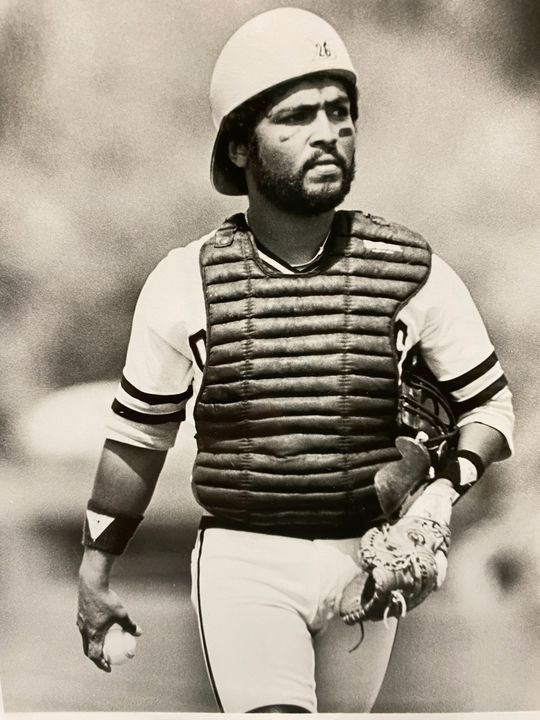

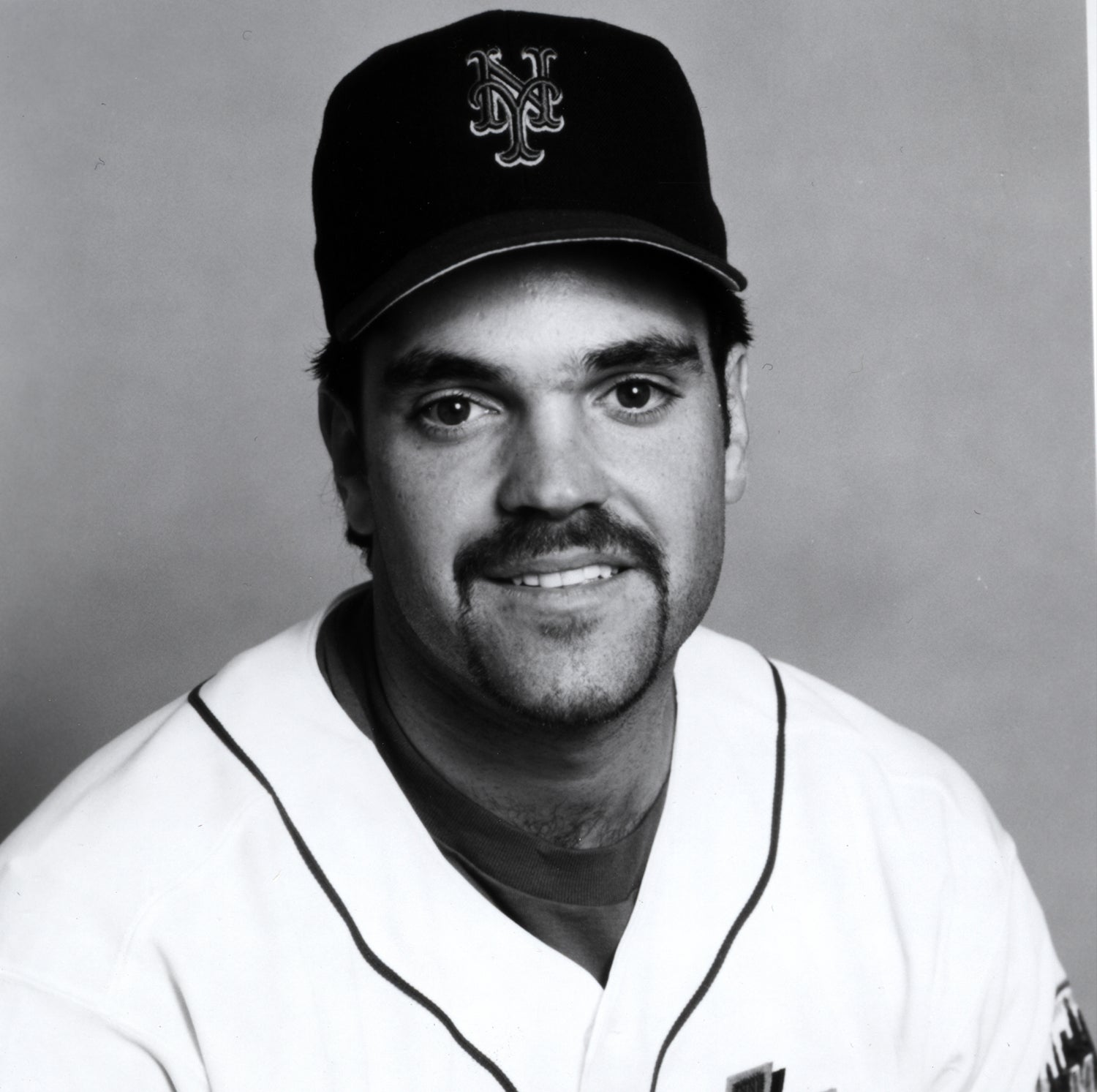

In 1980, showcasing his talent with the Buffalo Bisons, Junior Ortiz hit .346 with 79 runs scored, 12 homers and 78 RBI, earning a spot on the Eastern League All-Star team before being called up to the Pirates. (Courtesy Pittsburgh Pirates)

Share this image:

Ortiz made the Opening Day roster as Peña’s backup but saw little time throughout the season’s first five months. With Peña playing nearly every inning of every game, Ortiz appeared in just 15 contests through August despite the fact that Pittsburgh carried no other catchers on the roster. Ortiz made eight starts in September and October as the Pirates wound down a season where they lost 104 games.

Ortiz finished the season with a .292 batting average.

Following the season, Tanner was dismissed and replaced by Jim Leyland. And though the team was undergoing a massive rebuild, Ortiz found his job safe – thanks to unwavering support from Leyland.

Ortiz hit a splendid .336 off the bench in 1986, appearing in 49 games as Peña’s backup. Since that season, only five catchers have hit at least .336 and appeared in at least 49 games in one season: Mike Piazza (three times), Joe Mauer (twice), Jorge Posada, Iván Rodríguez and Don Slaught.

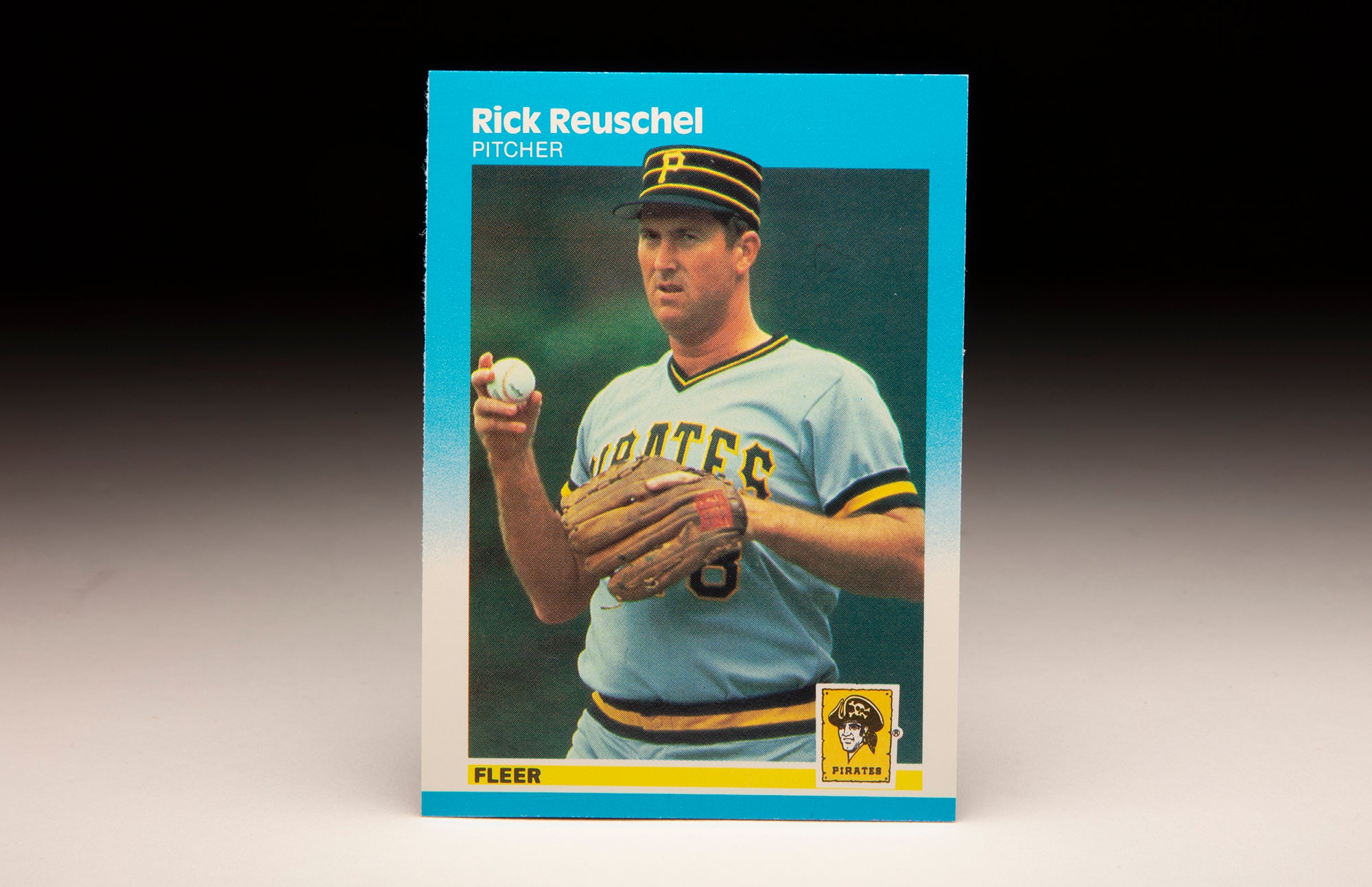

Then, on April, 1, 1987, the Pirates made a blockbuster trade that defined their future – sending Pena to the Cardinals for outfielder Andy Van Slyke, pitcher Mike Dunne and catcher Mike LaValliere.

“We were in St. Petersburg, playing the Cardinals, and (Pirates general manager) Syd (Thrift) came to me,” Ortiz told the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette following the trade. “At the time, I thought it was a strange question. He said: ‘Junior, I want to ask you something serious. No messing around.’ He asked me how many games did I think I could catch in a season.

“I said I thought I could play 85 or 90. After that, I was smelling something.”

With LaValliere a lefty-hitting catcher, Leyland suddenly had a platoon that looked viable.

“It’s not a bad trade,” Ortiz said about the deal. “We finished in last place the last three years, and I think this year we will not finish in last place.”

Ortiz proved correct as Pittsburgh went 80-82 in 1987, finishing fourth in the NL East. Ortiz and LaValliere split the catching duties, with LaValliere hitting .300 while winning the Gold Glove Award and Ortiz batting .271 while establishing career-highs in games (75), hits (52) and RBI (22).

The 1988 season saw the Pirates improve to 85-75 as Ortiz hit .280 in 49 games, once again platooning with LaValliere. But in the Pirates’ 11th game of the 1989 season – on April 16 – LaValliere suffered a severe left knee injury when the Expos’ Rex Hudler collided with him while scoring on a Nelson Santovenia single.

LaValliere missed the next two-and-a-half months of action, and Ortiz struggled at the plate as the regular catcher – hitting just .221 at the point where LaValliere returned in July.

By the end of the season, Ortiz was hitting .217 in 91 games and the Pirates brought in Don Slaught to be the right-handed half of their platoon when they executed a December trade with the Yankees.

On April 4, 1990, Pittsburgh traded Ortiz and minor leaguer Orlando Lind to the Twins in exchange for minor league pitcher Mike Pomeranz. At the time, no Pirates player had been with the team longer than Ortiz.

In Minnesota, Ortiz joined his former Pirates teammate Brian Harper as the Twins’ backstops. Harper, a right-handed hitter like Ortiz, hit .294 in his second full season as a starter while Ortiz hit .335 in 71 games as the backup. But Minnesota finished 74-88 and in last place in the AL West.

The 1991 season, however, would be a different story. Minnesota signed free agent pitcher Jack Morris to anchor the rotation, and Scott Erickson – who had gone 8-4 with a 2.87 ERA as a rookie in 1990 – blossomed into a 20-game winner in 1991.

Ortiz hit just .209 as Harper’s backup but became Erickson’s personal catcher – receiving praise from around the league for his handling of Erickson and other Twins pitchers.

Erickson preferred all-black socks and spikes – and painted Ortiz’s cleats to match.

“I told him we might as well look alike,” Ortiz told the Sioux Falls (S.D.) Argus-Leader. “And right now, we’re not going to change. It seems to work.”

After starting the season 2-9, the Twins caught fire and reeled off a 15-game winning streak in June. They won the AL West with a record of 95-67 and then defeated the Blue Jays in five games in the ALCS, with Ortiz catching Erickson in Game 3 – a 3-2 Minnesota win.

The Twins appeared poised to face Ortiz’s former team, the Pirates, in the World Series – but the Braves rallied from a 3-games-to-2 deficit to defeat Pittsburgh.

“I was really mad,” Ortiz told the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette after the Pirates lost Game 7 to the Braves in the NLCS. “Jim Leyland deserves to be in a World Series. He’s a great manager.”

In the World Series, Ortiz started behind the plate in Erickson’s starts in Games 3 and 6 and totaled one hit in five plate appearances overall as the Twins won in seven games. When Gene Larkin delivered his World Series-winning pinch-hit in the 10th inning of Game 7, Ortiz was the only position player remaining on the Twins’ bench.

“Since I’ve been in the big leagues, my dream was to be in a World Series,” Ortiz told The New York Times. “To be able to say, after I retire, that I was there.”

Following the World Series, Ortiz became a free agent – and on Dec. 16, he signed a minor league deal with the Indians. He won the job as Sandy Alomar Jr.’s backup in Spring Training and appeared in 86 games as Alomar battled injuries, hitting .250 with 24 RBI. A year later, Ortiz appeared in 95 games – the most of any Cleveland catcher as Alomar was again hurt – hitting .221 while helping a youthful Indians staff featuring José Mesa, Charles Nagy and Mark Clark.

But as he did in Pittsburgh, Ortiz changed teams just before the Indians became postseason contenders when he was traded to the Rangers on March 23, 1994, in exchange for players to be named later that became minor leaguers Igor Oropeza and Andreaus Lewis.

Ortiz hit .276 in 29 games as the backup to Iván Rodríguez during a season that was cut short by a strike. He signed with the White Sox as a free agent on Dec. 9, 1994, but when the strike was not resolved he became a replacement player in March of 1995. He had more years of service than any of the other replacement players.

“Since I don’t know how long I am going to play in the big leagues, this is a new opportunity for me,” Ortiz told the Associated Press. “I will take all the heat. That was the decision I chose.”

But when the strike ended in April, Ortiz had no place on the White Sox’s roster and was sent to Triple-A Nashville. He batted .186 in 64 games that season, never receiving a chance to return to the majors – in 1995 or ever again.

“Obviously, if I had to do this all over again, I would have never crossed the line,” Ortiz told The Record of Hackensack, N.J. “I did something wrong and now I’m paying for it.”

Ortiz finished his 13-year career with a .256 batting average over 749 games, totaling 484 hits and 186 RBI. Defensively, he posted a .986 fielding percentage and threw out 32 percent of the runners who tried to steal on him – which was right in line with the league average for the seasons he played. In four of his final five big league seasons, Ortiz threw out more than 40 percent of runners trying to steal.

But beyond the stats, Ortiz left a legacy as a dependable backup catcher – and a popular teammate.

“He’s got a joyful personality,” Scott Erickson told The New York Times about Ortiz during the 1991 World Series. “That always pays off, no matter what you’re doing, don’t you think?”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Official Hall of Fame Merchandise

Hall of Fame Members receive 10% off and FREE standard shipping on all Hall of Fame online store purchases.