- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1988 Topps Frank Lucchesi

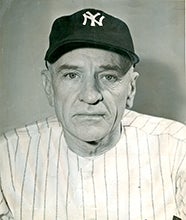

#CardCorner: 1988 Topps Frank Lucchesi

Over the weekend, I was doing some remote control surfing (or channel changing, as we used to say back in the day), when I stumbled across a favorite old movie: The 1983 version of Scarface, directed by Brian de Palma. At one time derided as an overly violent and soulless film, Scarface has gained in appreciation over the years, to the point where it is genuinely regarded as a cult classic in the genres of crime, mafia and action movies.

One of the main characters in the film is the affable but laughable cartel leader Frank Lopez, played so beautifully by the late character actor, Robert Loggia. With his distinctive look, raspy voice, and ability to portray both malicious and sympathetic characters, Loggia became one of my favorite character actors, a versatile sort who could handle comedy, drama and virtually everything in between.

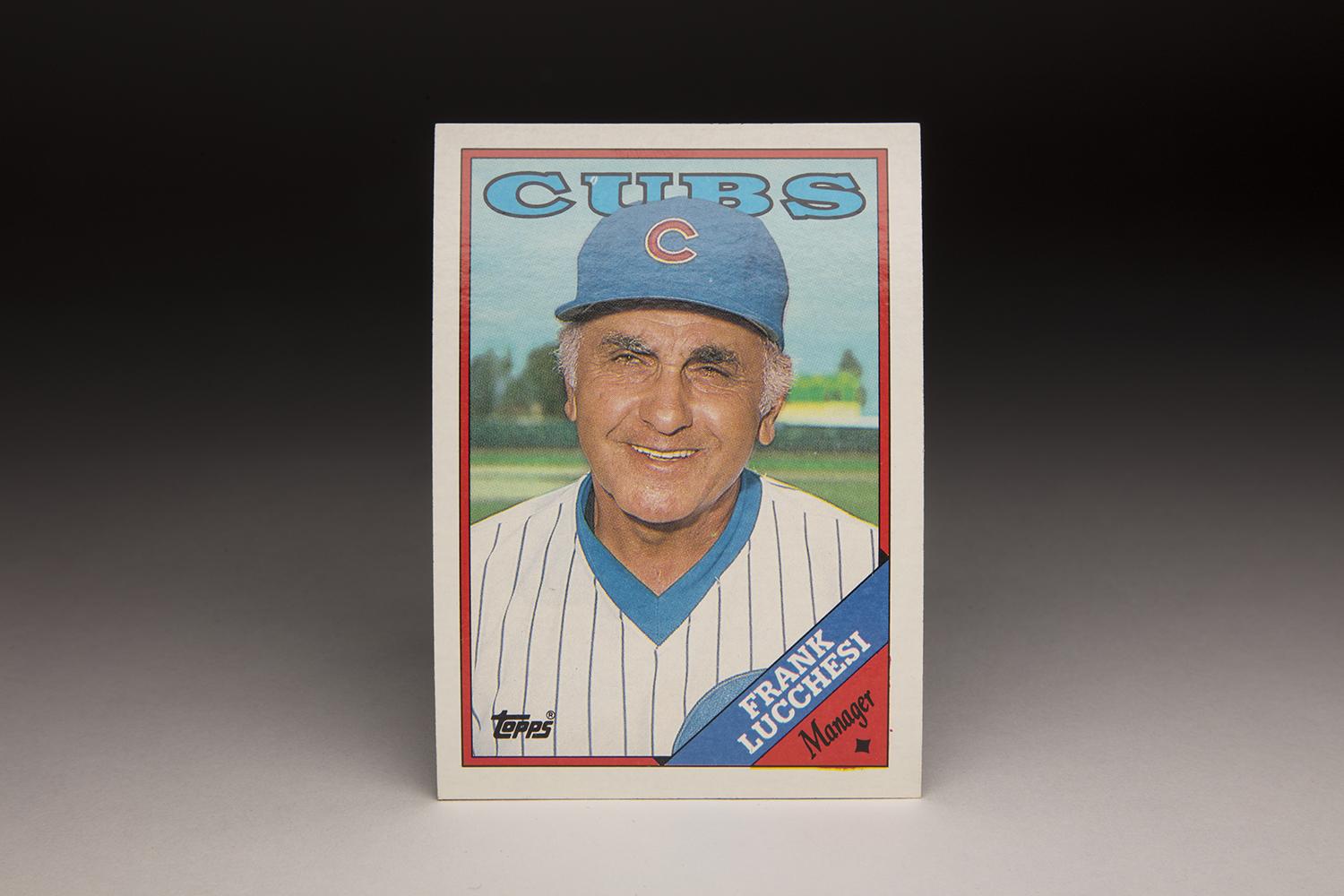

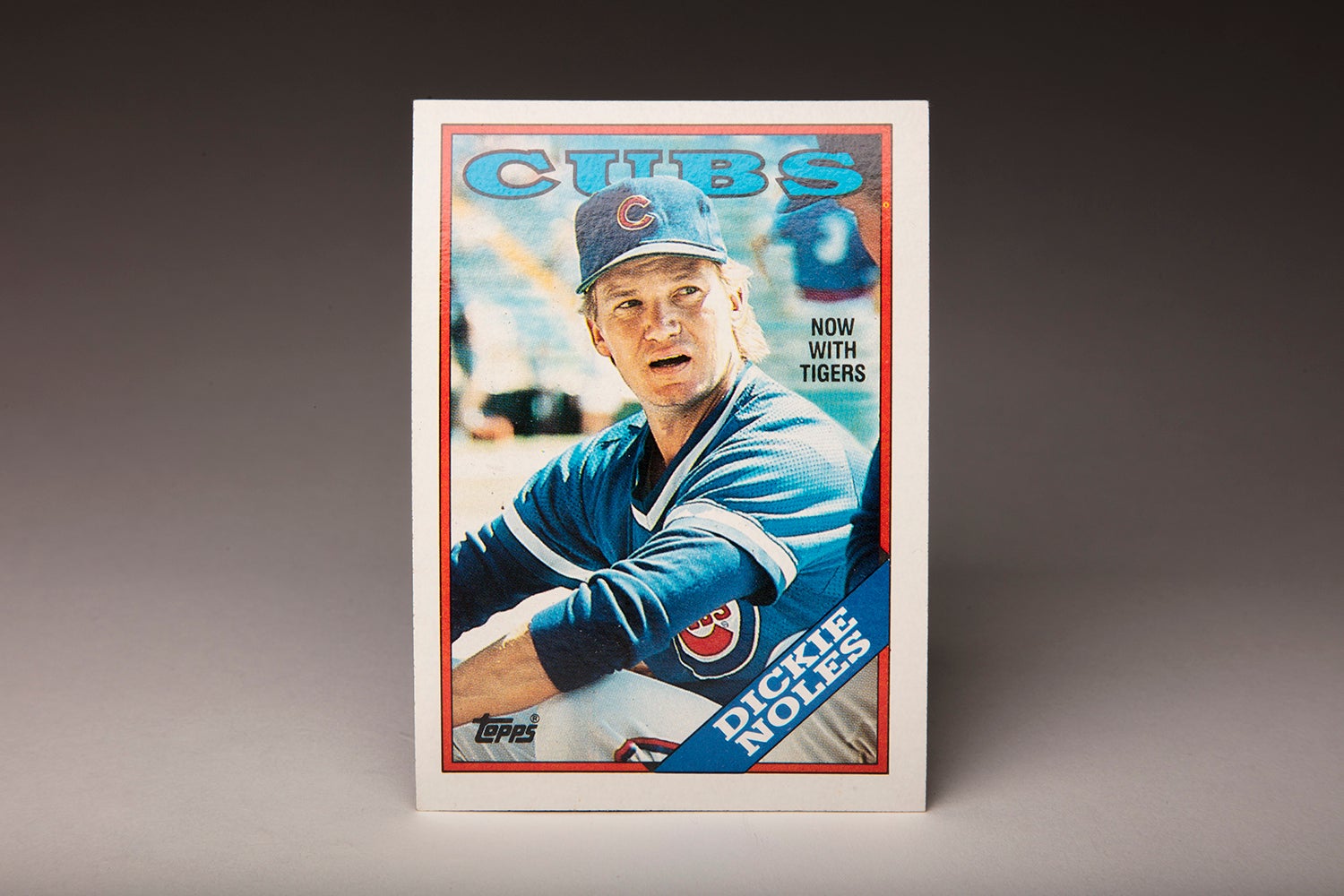

Shortly after watching Scarface for about the 47th time, I happened to stumble upon a 1988 Topps card of Chicago Cubs manager Frank Lucchesi. I was immediately struck by how much Lucchesi, in the late 1980s, looked like Loggia, or at least a slightly heavier version of the actor. From the thick, dark eyebrows to the gray hair to the tanned skin, the likenesses in their features could have made them brothers. The coincidence of Loggia playing a character named Frank also gave them another point in common.

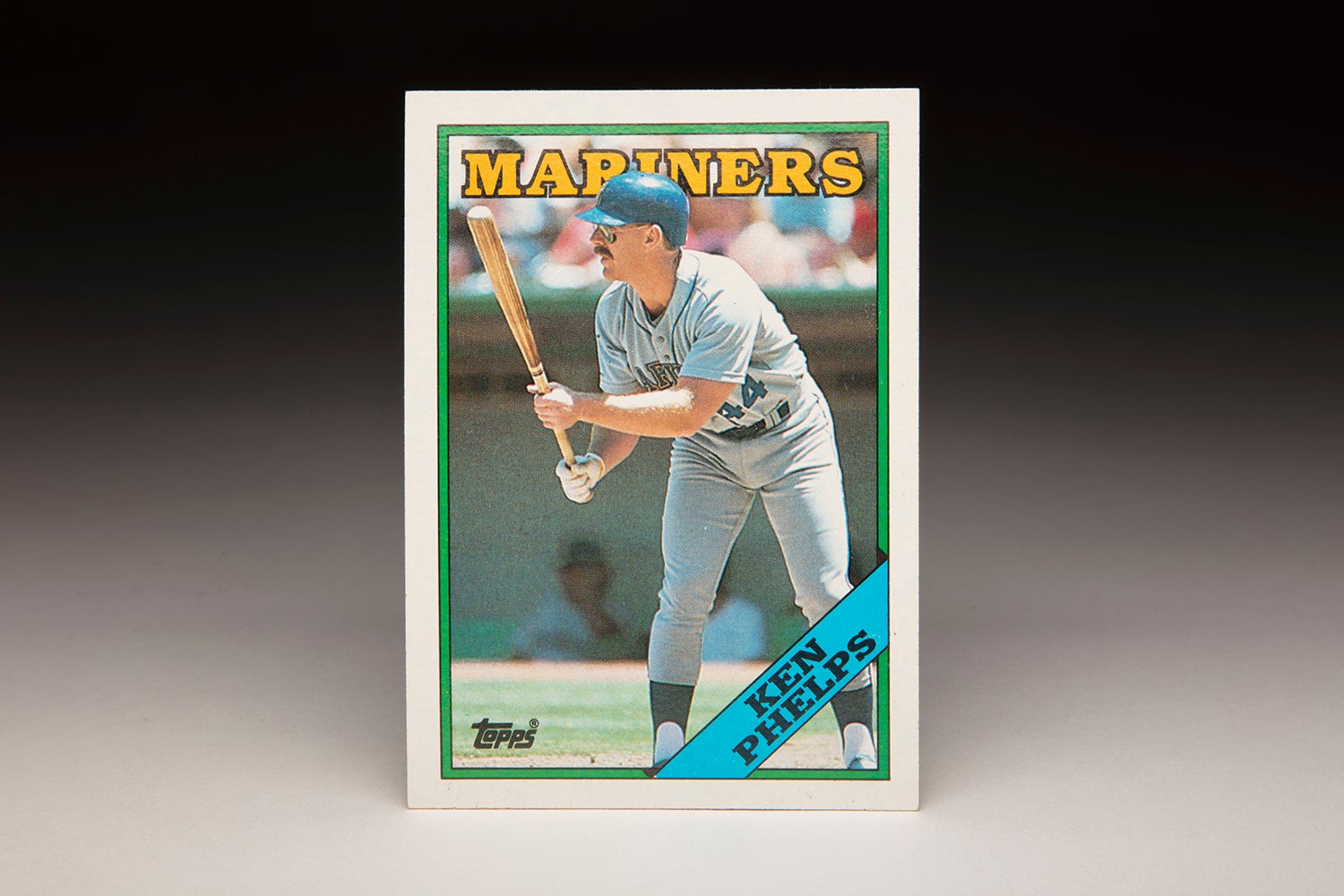

For Frank Lucchesi (pronounced Loo-KAY-zee), his 1988 Topps card was his swansong in the major leagues. He had not managed at that level since being fired by the Rangers in 1977, only to return to the dugout as the Cubs’ interim manager at the tail-end of the 1987 season. The Cubs then replaced Lucchesi after the ’87 season, making his 1988 card somewhat obsolete and bringing his major league managerial days to an end. Lucchesi would manage in the minor leagues in 1988, but his days as a big league field boss were done.

While manager cards are generally not as desirable as player cards, they are sometimes just as interesting. Billy Martin’s 1972 Topps “In Action” card shows him arguing with an umpire. Several cards of the 1960s show the manager with his hand cupped over his mouth, as he is barking out orders to his players. In Lucchesi’s case, we not only see the similarity to a famous character actor, but we also see a manager who is distinctly older, one who is closer to the end of his career than he is to the beginning. At the time this photograph was taken, Lucchesi was already 60 years old. In today’s game, where field managers seem to be hired at younger and younger ages, Lucchesi would have stood out as a Methuselah among big league skippers.

Lucchesi also represented an exception to the rule on another front. Unlike the majority of managers, Lucchesi never played in the major leagues. His professional playing career began in 1945, when he signed with the independent Portland Beavers of the Pacific Coast League. That was as high as he would advance. The following year, he found himself playing in the Class B Western International League (WIL). From there, he signed with the New York Yankees’ organization, which assigned him to Victoria, also in the WIL.

A moderately talented outfielder who stood only 5-foot-7, Lucchesi lacked power and strong hitting skills. As Lucchesi once told the Associated Press, a conversation with a Yankee scout made it quite clear that he was not a prospect. “Joe Devine told me once that the closest I’d ever get to Yankee Stadium as a player was to see it on a postcard,” Lucchesi recalled while laughing. Instead, Lucchesi survived on speed, hustle, and defense, along with a sense of determination shown by few other players. He also displayed enough of a mental grasp of the game that he became a player/manager for Medford in 1951.

Tragedy nearly ended his career only three years later. It was May of 1954, while Lucchesi was managing Pine Bluff of the Cotton State League. A vicious line drive hit him in the head. The incident forced him to undergo brain surgery in order to remove a blood clot that had developed.

Even after the surgery, the perseverant Lucchesi continued to manage and play, even though he was bothered by lingering side effects. By 1956, doctors told him that he should retire from playing and stick to managing. He followed their orders, only to return to playing duty two months later when one of his outfielders went down with an appendectomy. Lucchesi played out the season, then accumulated one more at-bat in 1957, before retiring as a player. That allowed him to concentrate fully on managing, and eventually led to an association with the Philadelphia Phillies.

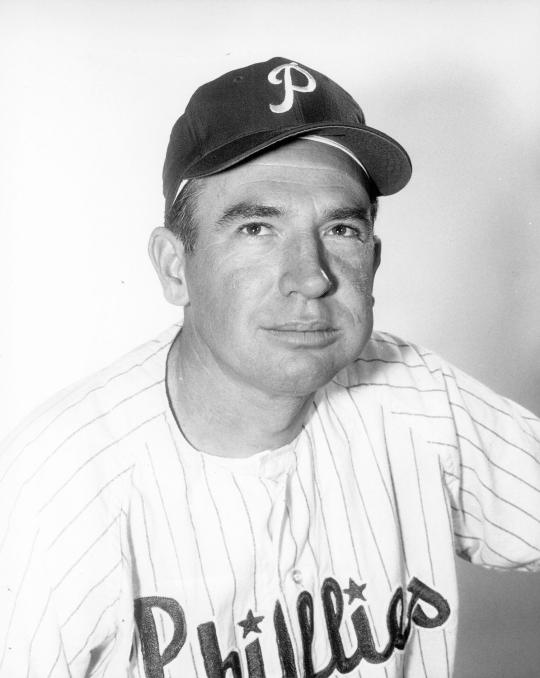

Working within the Phillies’ system, Lucchesi became a highly accomplished minor league manager. Over the span of 13 seasons, he guided his clubs to six pennants, while taking home five Manager of the Year titles. He showed a penchant for developing prospects, including future big leaguers like Dick Allen, Larry Bowa, Rick Wise and Ferguson Jenkins.

Lucchesi also established a colorful reputation. Fiery and intense, he willingly took on umpires who ruled against his team. While managing at Chattanooga, Lucchesi argued with the home plate umpire, who promptly ejected him. Not wanting to leave, Lucchesi sat down on home plate. He refused to leave, at least until ballpark security physically removed him from his perch.

Lucchesi was also highly quotable, making him a favorite of the local media. On one occasion, he took a quote from John F. Kennedy and twisted it to make it appropriate for baseball. “It’s not what the ballclub can do for you,” Lucchesi told his players, “but what you can do for the ballclub.” He also featured a streak of Casey Stengel, once referring to “amphetamines” as “amphibians.”

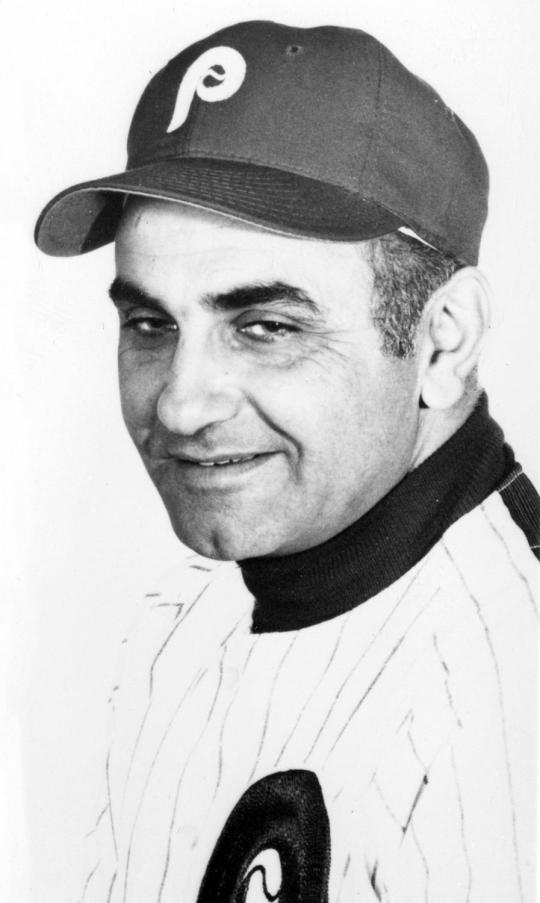

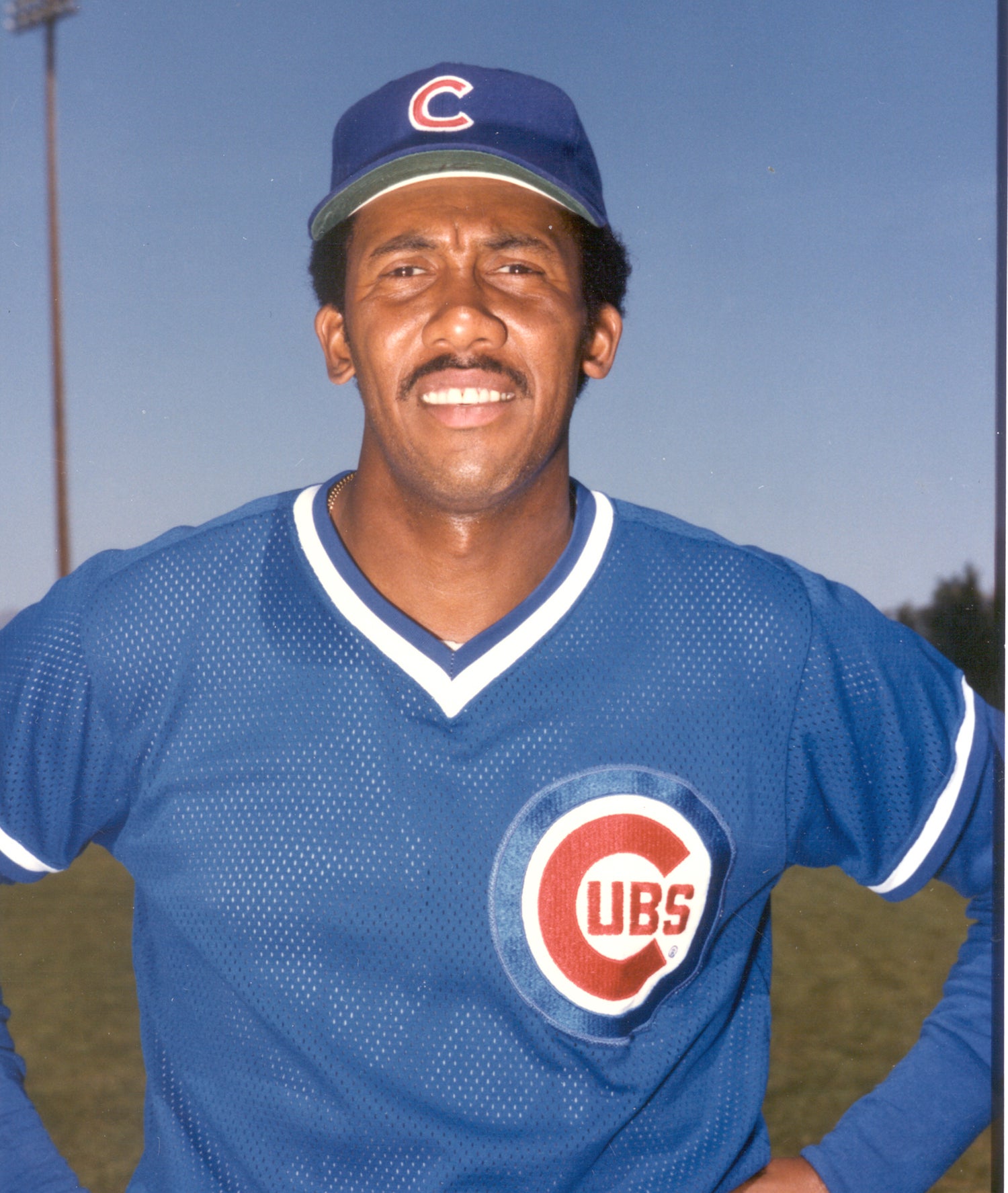

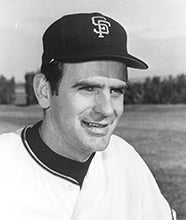

For all of his minor league success, Lucchesi found himself blocked by the Phillies’ major league manager, Gene Mauch. Known as one of the game’s most intelligent field bosses, Mauch remained on the job through the middle of the 1968 season, when a feud with Allen resulted in him losing his job. Some Phillies insiders thought the organization would turn to Lucchesi, but his minor league teams had struggled for three straight seasons, finishing under .500 each time. Rather than tab Lucchesi, the Phillies gave the job to one of their coaches, Bob Skinner.

At the end of the 1969 season, the Phillies finally gave Lucchesi the chance to manage. Soon after, the Phillies traded Allen, further fueling speculation that Lucchesi and Allen had feuded while both toiled at Little Rock in 1963. Lucchesi later denied the allegation, maintaining that he and Allen had gotten along well. For his part, Allen maintained that Lucchesi had offered him little support during his difficult days in Little Rock, when the young slugger dealt with a torrent of racial abuse.

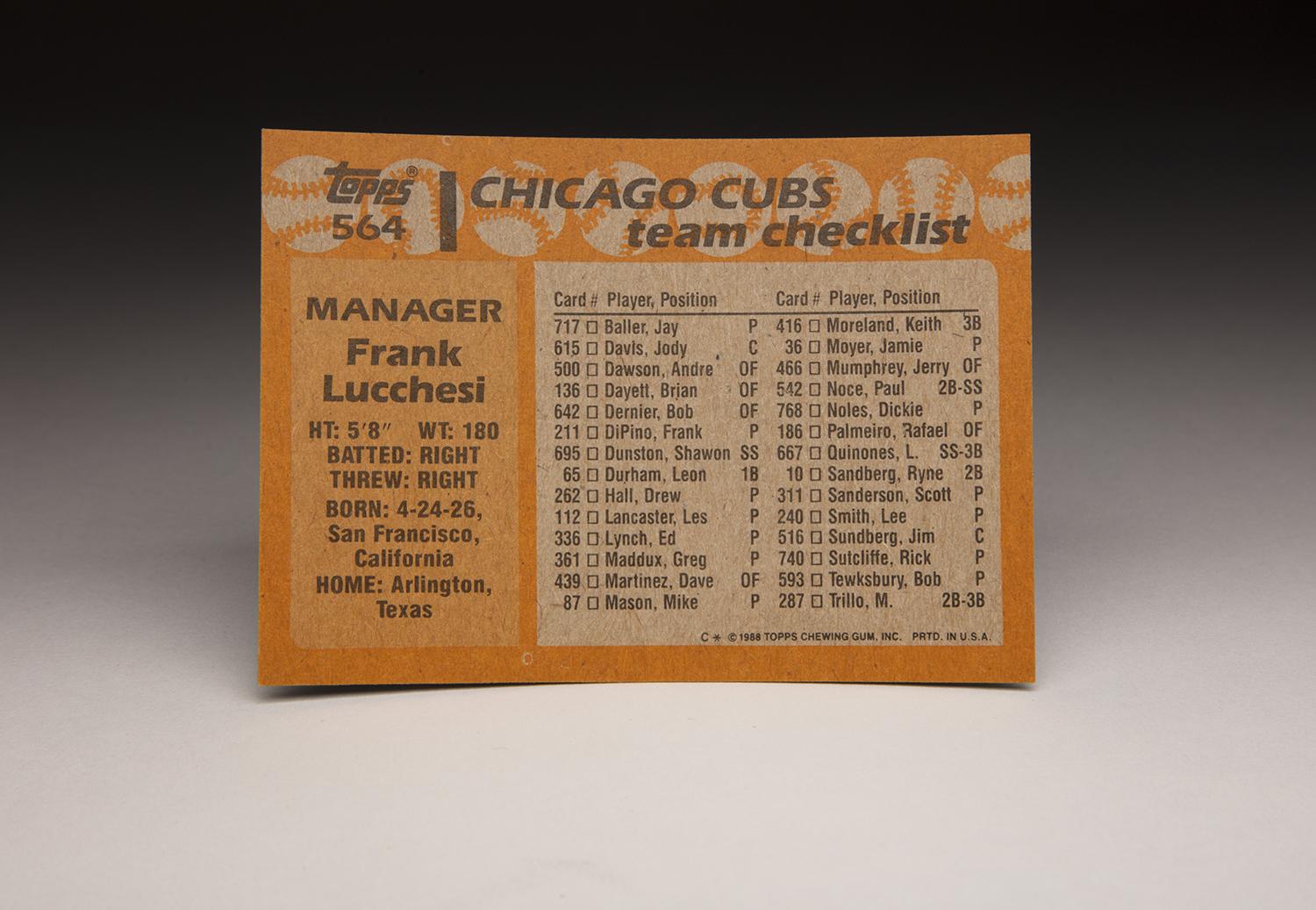

In contrast to Allen, the city of Philadelphia reacted warmly to the news of Lucchesi’s hiring, in part because of the large local Italian-American population. On April 7, 1970, he made his managerial debut for the Phillies at Connie Mack Stadium, where he received a standing ovation. When he saw the show of support, he could not contain himself emotionally.

“It was an honor,” Lucchesi said many years later in an interview with Ken Mandel of MLB.com. “When they introduced me, I got a standing ovation and it brought tears to my eyes. I still have the picture on my wall. The press wrote about how long I had waited and how I was an underdog.”

As the Phillies’ rookie skipper, Lucchesi stressed speed and defense. The Phillies responded by committing the fewest errors in the National League, running the bases aggressively, and improving their win total by 10 games in 1970. Thanks to such improvement, Lucchesi earned some support in the NL Manager of the Year balloting.

While the Phillies showed improvement under Lucchesi, they generally lacked the kind of talent needed to escape the second division. In 1971, their projected starters at shortstop and third base combined to hit no home runs. Their corner outfielders did not produce, either for average or power. And in the Phillies’ starting rotation, only one pitcher (Rick Wise) posted a winning record and an ERA under 3.00. Lucchesi tried all sorts of remedies, including the onetime selection of his starting lineup out of a hat, but nothing worked. It all added up to a last-place finish in the National League East.

The situation only worsened in 1972. At the same time, Lucchesi had to deal with a personal struggle: The illness of his wife. (She would eventually recover, but the situation put a strain on Lucchesi.) After a good start to the season, the Phillies endured a brutal slump. At one point, they lost 19 of 20 games. By July, their record stood at 26 wins and 50 losses, costing Lucchesi his job. Several Philadelphia writers, citing Lucchesi’s understanding of the game, felt that the firing was completely unjust.

Even after his firing, Lucchesi continued to show a caring side to his personality. Before being let go, he had promised a six-year-old boy undergoing heart surgery that he would be his guest for a day at Veteran Stadium. Even though he was now out as Phillies skipper, Lucchesi made sure to follow through on his promise.

At first, Lucchesi chose to remain with the organization in a lesser role, but he found the situation awkward and left the Phillies completely. Rumors swirled that he might join the San Diego Padres as a coach, or the Rangers as their manager, succeeding Ted Williams. None of those jobs came to fruition. Instead, Lucchesi agreed to manage the Oklahoma 89ers of the American Association in 1973.

After one season back in the minor leagues, Lucchesi returned to the major leagues – this time as Billy Martin’s third base coach with the Rangers. Lucchesi became Martin’s chief lieutenant and also emerged as a sometime manager. With the volatile Martin often on the receiving end of umpire ejections, Lucchesi found himself managing the Rangers from time to time.

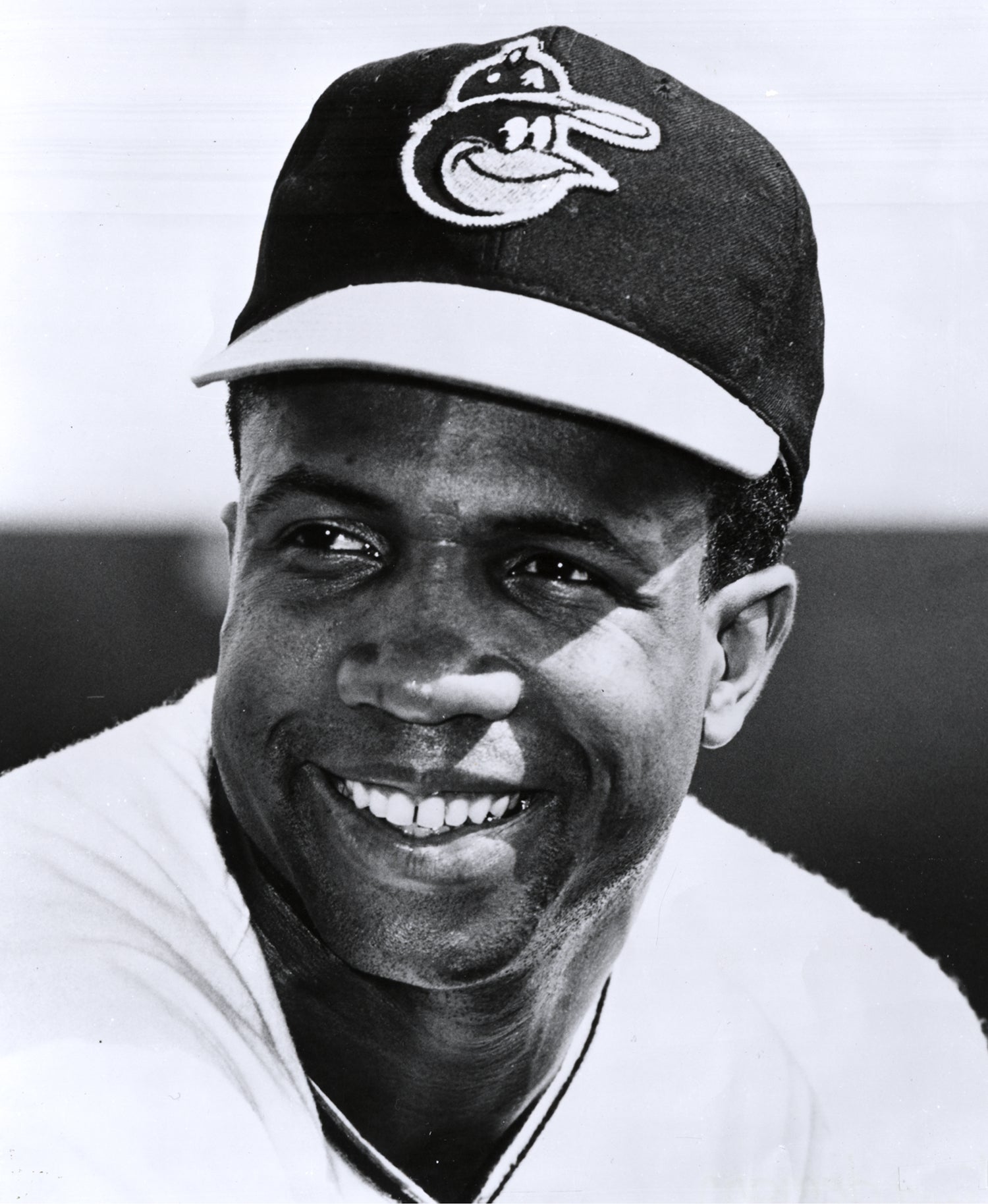

In October of 1974, the Cleveland Indians sought a replacement for their fired manager, Ken Aspromonte. Among the rumored candidates to fill the position was Lucchesi. It’s not clear if the Indians actually interviewed Lucchesi, but they instead made national news by choosing Frank Robinson, who became the first black manager in the major leagues. So Lucchesi returned to the Rangers’ coaching staff for the 1975 season.

The Rangers did not play well for Martin in 1975. With a record seven games below .500, the Rangers fired Martin on July 20. They offered Lucchesi the chance to manage the team, at least on an interim basis. At first, Lucchesi hesitated, because of his closeness to Martin; he didn’t want to be seen as somebody who had positioned himself to replace his friend. Ultimately, Lucchesi accepted the Rangers’ offer, a decision that angered Martin and led to a falling out.

As the Phillies had done previously, the Rangers showed immediate improvement under Lucchesi, winning 35 games against 32 losses over the balance of the season.

The team’s late-season performance convinced the Rangers to bring Lucchesi back for the 1976 season.

On April 7, 1970, Frank Lucchesi made his managerial debut for the Phillies at Connie Mack Stadium, where he received a standing ovation. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

After Gene Mauch was dismissed as Phillies' manager mid-way through the 1968 season, the Phillies turned to Bob Skinner (pictured above). (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

The Phillies’ starting rotation under Frank Lucchesi in 1971 had only one pitcher (Rick Wise, pictured above) post a winning record and an ERA under 3.00. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

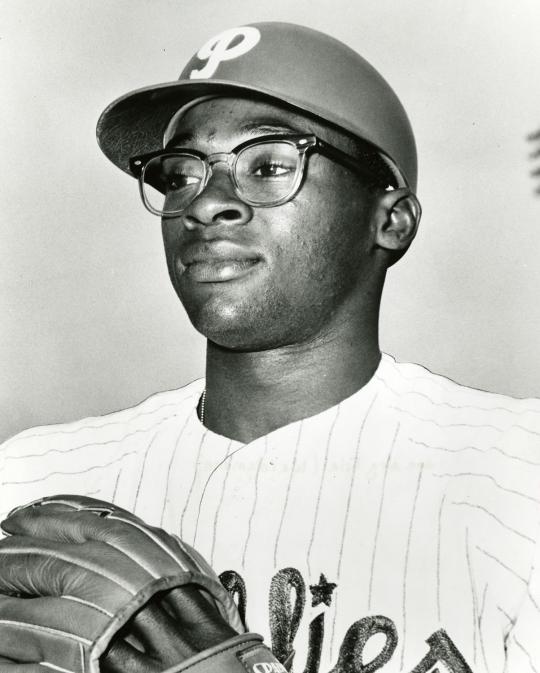

While working in the Philadelphia Phillies' farm system, Frank Lucchesi showed a penchant for developing prospects, including future big leaguers like Dick Allen (pictured above), Larry Bowa, Rick Wise and Ferguson Jenkins. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

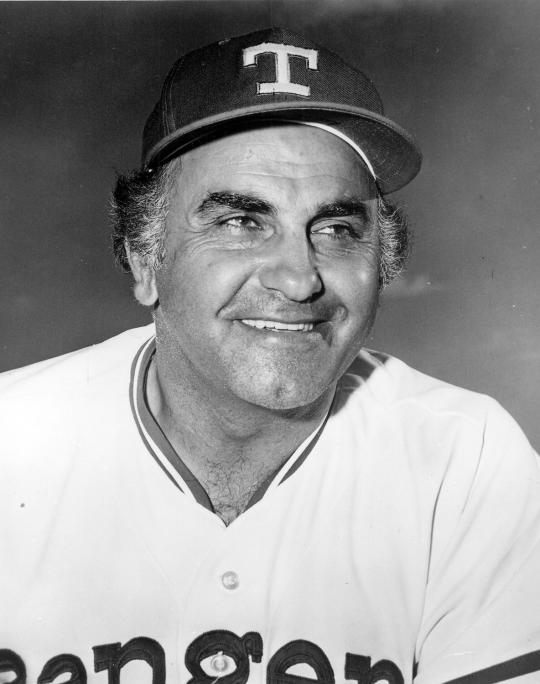

After serving as Billy Martin’s third base coach with the Texas Rangers, Frank Lucchesi became the team’s manager in 1975. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

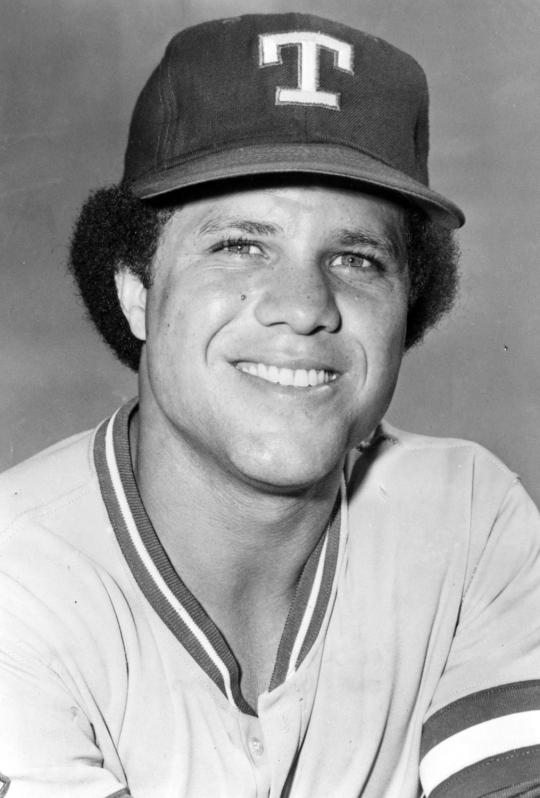

While serving as Rangers manager in the spring of 1977, Frank Lucchesi had to choose between veteran Lenny Randle and rookie Bump Wills (pictured above) as the team’s starting second baseman. Lucchesi’s selection of Wills led to a confrontation between the manager and Randle. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

The Rangers played well to begin the season, winning 20 games and losing 12 over the first five weeks. But Lucchesi never felt comfortable, mostly because of the presence of owner Brad Corbett, who was known for meddling in the affairs of the team. Eventually, the Rangers slumped, enduring a terrible stretch of play in July and August. They would finish the season under .500, and though Lucchesi would receive a contract extension that winter, he felt anything but secure.

The spring of 1977 would put Lucchesi in the national spotlight, but for the most unwanted of reasons. The situation initially involved a battle for the Rangers’ second base job between veteran Lenny Randle and rookie Bump Wills, the son of the great Maury Wills.

Based on the early weeks of Spring Training, Lucchesi appeared to favor Wills. Lucchesi played Wills about twice as often as the veteran Randle. Randle believed Wills was receiving preferential treatment. Although Lucchesi praised Randle as the “hardest worker we have in camp,” he soon announced that Wills had won the job.

On March 24, Randle rushed into the Texas clubhouse, packed up his clothes, and told reporters that he was leaving camp. Two of Randle’s Rangers teammates, Mike Hargrove and Gaylord Perry, talked to the unhappy infielder and advised him to remain at Spring Training. They suggested that Randle try to work out the situation with Lucchesi. Randle took their advice.

When Lucchesi learned about Randle’s planned departure and subsequent change of mind, he told the media that he would have preferred that Hargrove and Perry did not speak to Randle at all. “I wish they’d have let him go,” Lucchesi said. “If he thinks I’m going to beg him to stay on this team, he’s wrong. I’m sick of punks making $80,000 a year moaning and groaning about their situation.” In 1977, a salary of $80,000 was regarded as good money, even with the advent of free agency.

Yet, it really wasn’t the reference to Randle’s salary that irritated the situation. It was Lucchesi’s choice of the word “punks.” The Texas media ran with Lucchesi’s characterization, saying that “punks” carried racial implications, especially when coming from a white manager in describing a black player. Lucchesi would not apologize to Randle for his use of the word, but he reportedly confided to coaches that he regretted using the word in describing the infielder.

Usually pleasant and outgoing, Randle showed little immediate anger over the remark. In fact, he repeatedly joked with teammates about being a “punk.” A few days later, Randle approached Lucchesi on the field prior to an exhibition game against the Minnesota Twins in Orlando, Fla. The two men appeared to be having a calm, civil conversation. Then, without warning, Randle threw a punch at Lucchesi, hitting him in the side of the face. Still wearing street clothes, the 49-year-old manager fell to the ground and landed on his backside. Randle punched him two more times, putting Lucchesi flat on his back. As Randle started toward Lucchesi again, Rangers shortstop Bert Campaneris interceded, pushing his teammate away and preventing additional damage.

Lucchesi suffered a litany of injuries: three fractures to his cheekbone, a concussion, two broken ribs, and an injured back. Rangers management responded quickly to the act of violence, announcing the suspension of Randle for 30 games. Additionally, the Rangers fined Randle $10,000, a substantial amount at a time when most players made under $100,000 in a season.

Remarkably, Lucchesi would return to manage the Rangers only eight days after the incident. But neither he nor Randle would last the season in Texas. Once the suspension ran its course, the Rangers traded Randle to the New York Mets for a player to be named later (infielder Rick Auerbach). As for Lucchesi, he guided the team to a record of .500 in the early months of the season, but feuded with general manager Eddie Robinson. On June 22, with the Rangers only four games out of first place in the American League West, Robinson fired Lucchesi.

In retrospect, Lucchesi felt that the incident with Randle had expedited his firing. At one point, he sued Randle, before settling the case out of court. Randle would offer apologies to Lucchesi on numerous occasions, but the manager refused to accept them, reportedly because of his bitterness over losing his job.

Though no longer the manager, Lucchesi decided to remain with the organization as a scout and then returned to a uniformed role as a coach in 1979 and ’80. From there, he took a minor league managing job with the Cleveland Indians, and put in some time as a coach with the Dodgers and Cubs. When the Cubs decided to fire Gene Michael as their manager, general manager Dallas Green approached Lucchesi about taking the position on an interim basis. The Cubs played miserably for Lucchesi, winning only eight of 25 games, but the players liked their short-term manager, admiring him for his knowledge and toughness.

Even though Lucchesi was strictly an interim hire, Topps put out a card for him as part of its 1988 set. It would turn out to be his final baseball card. Yankees owner George Steinbrenner approached Lucchesi about becoming a scout. Billy Martin, having reconciled with Lucchesi, had urged Steinbrenner to make the offer, but Lucchesi turned it down, instead taking a job as a minor league manager. After the 1989 season, Lucchesi retired for good and returned to his home in Texas, where he lived until his death on June 8, 2019.

All these years later, it’s somewhat disheartening that Lucchesi is still best known for being on the receiving end of an attack from a player. Perhaps now a few people will also take note of his curious resemblance to Robert Loggia.

Better yet, it would be nice for people to recognize Lucchesi as a man who was dedicated to baseball for five decades, as a player, coach, scout, and manager. The term “baseball lifer,” the ultimate compliment that can be given in our game, would fit Frank Lucchesi to a T.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum