- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1966 Topps John Blanchard

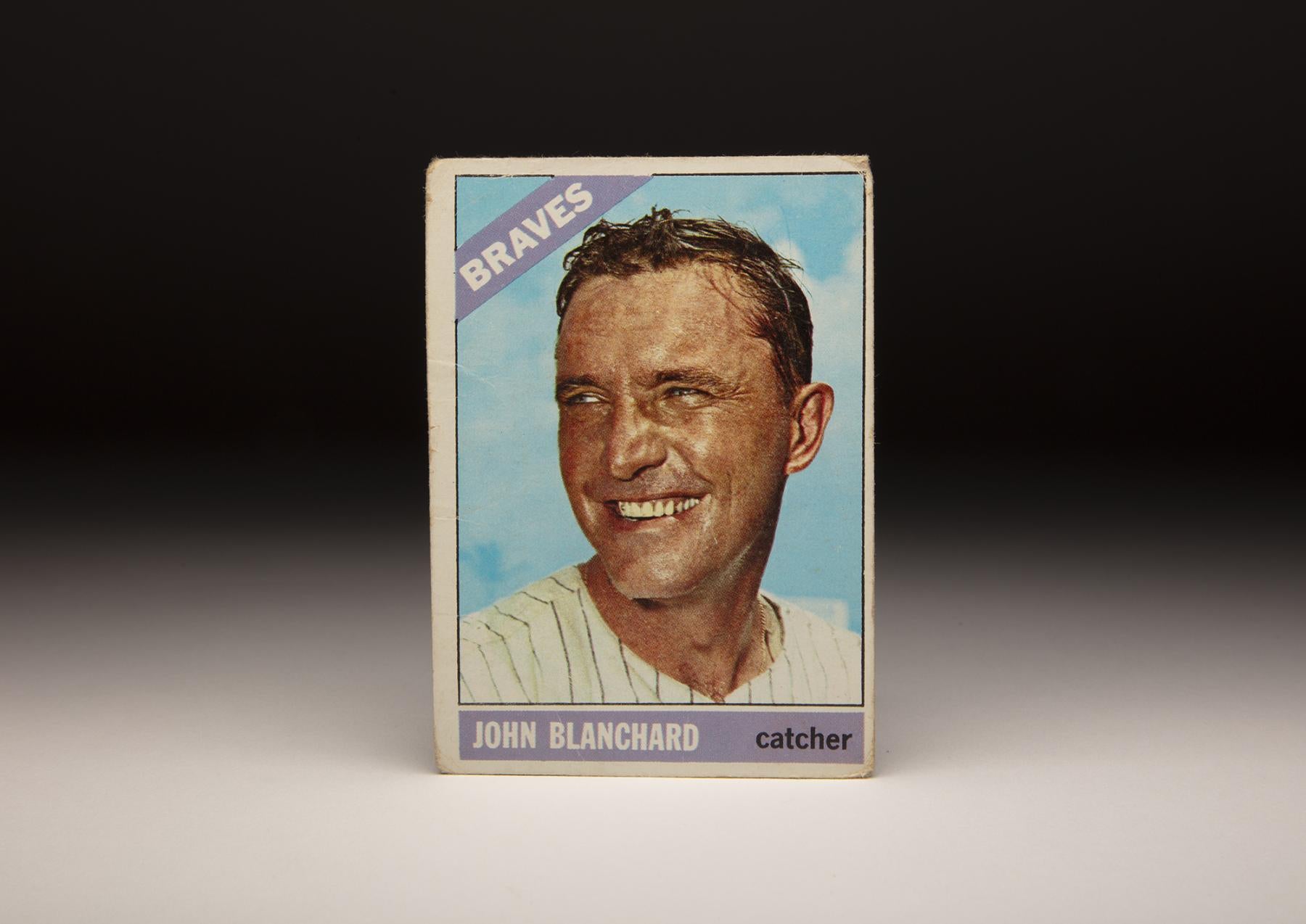

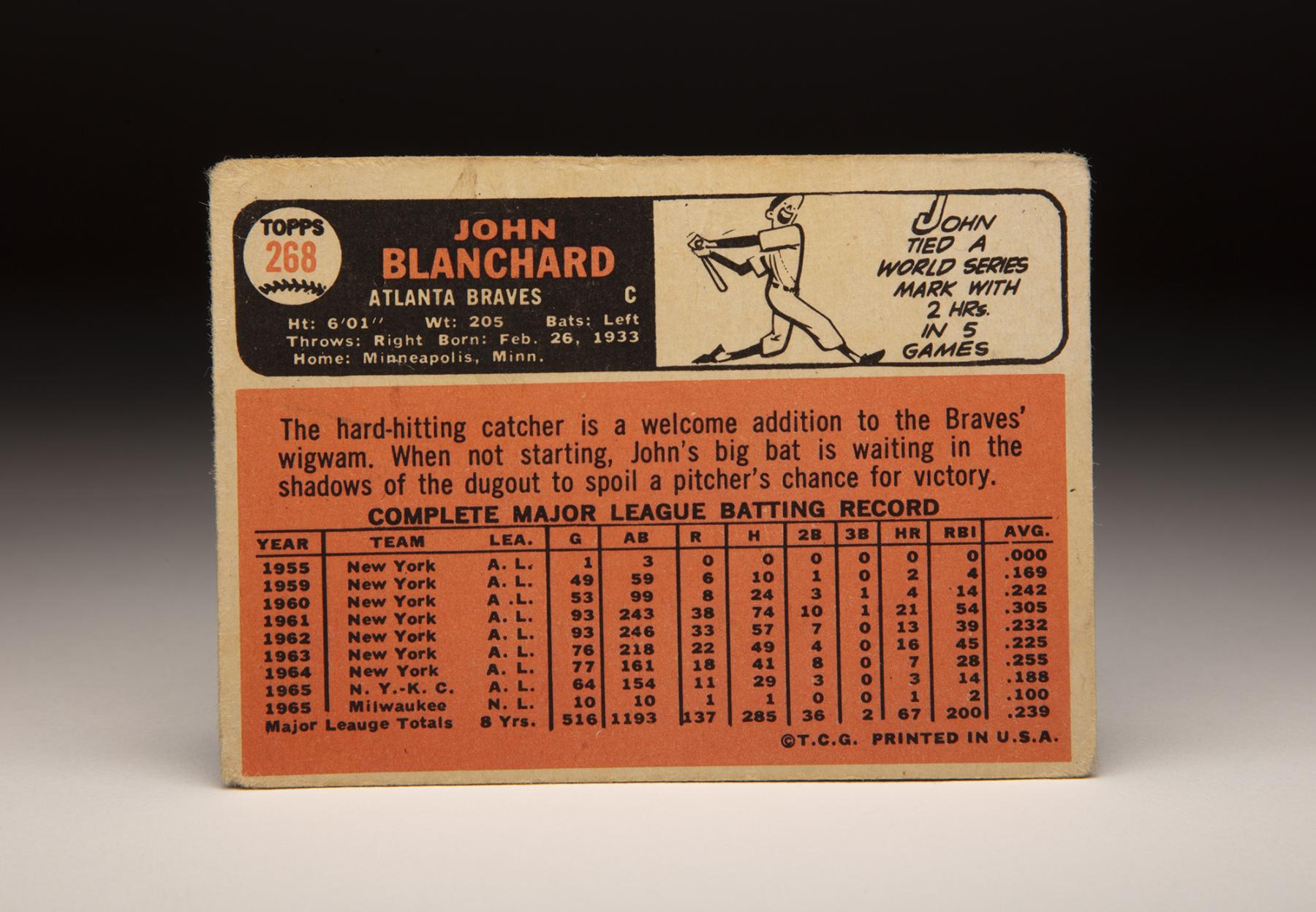

#CardCorner: 1966 Topps John Blanchard

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

I don’t think I had ever heard of the word “grizzled” before I started following baseball.

It’s a legitimate word in the English dictionary, one that means “having gray hair,” but it’s a word that doesn’t seem to come up in everyday conversation too often, or even in written form. Yet it is a word that has become common in the baseball vernacular, a word that is often used to describe a veteran player, likely in his 30s or older, who has a shop-worn look that affects most of us as we age. There is also a connotation of a player who has been toughened by his long service to the game.

Official Hall of Fame Apparel

Proceeds from online store purchases help support our mission to preserve baseball history. Thank you!

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

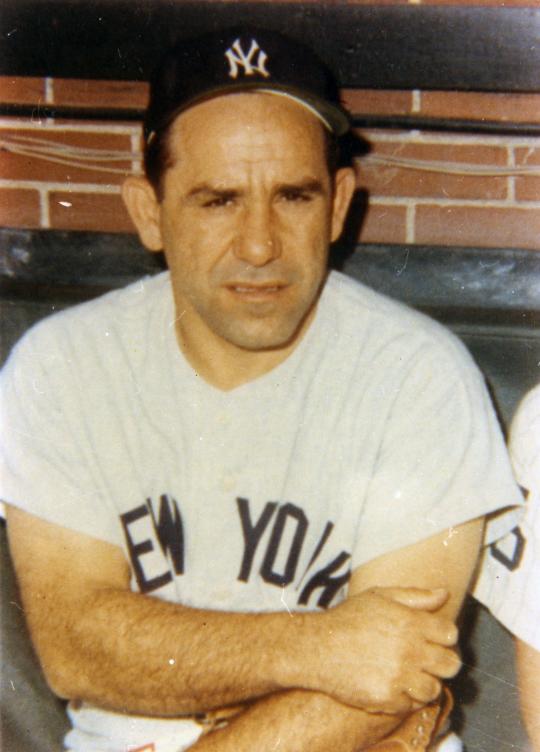

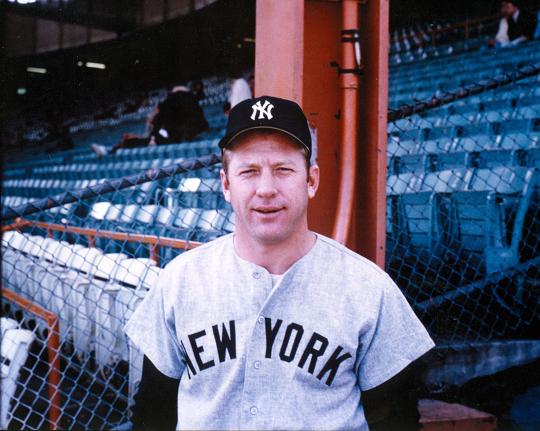

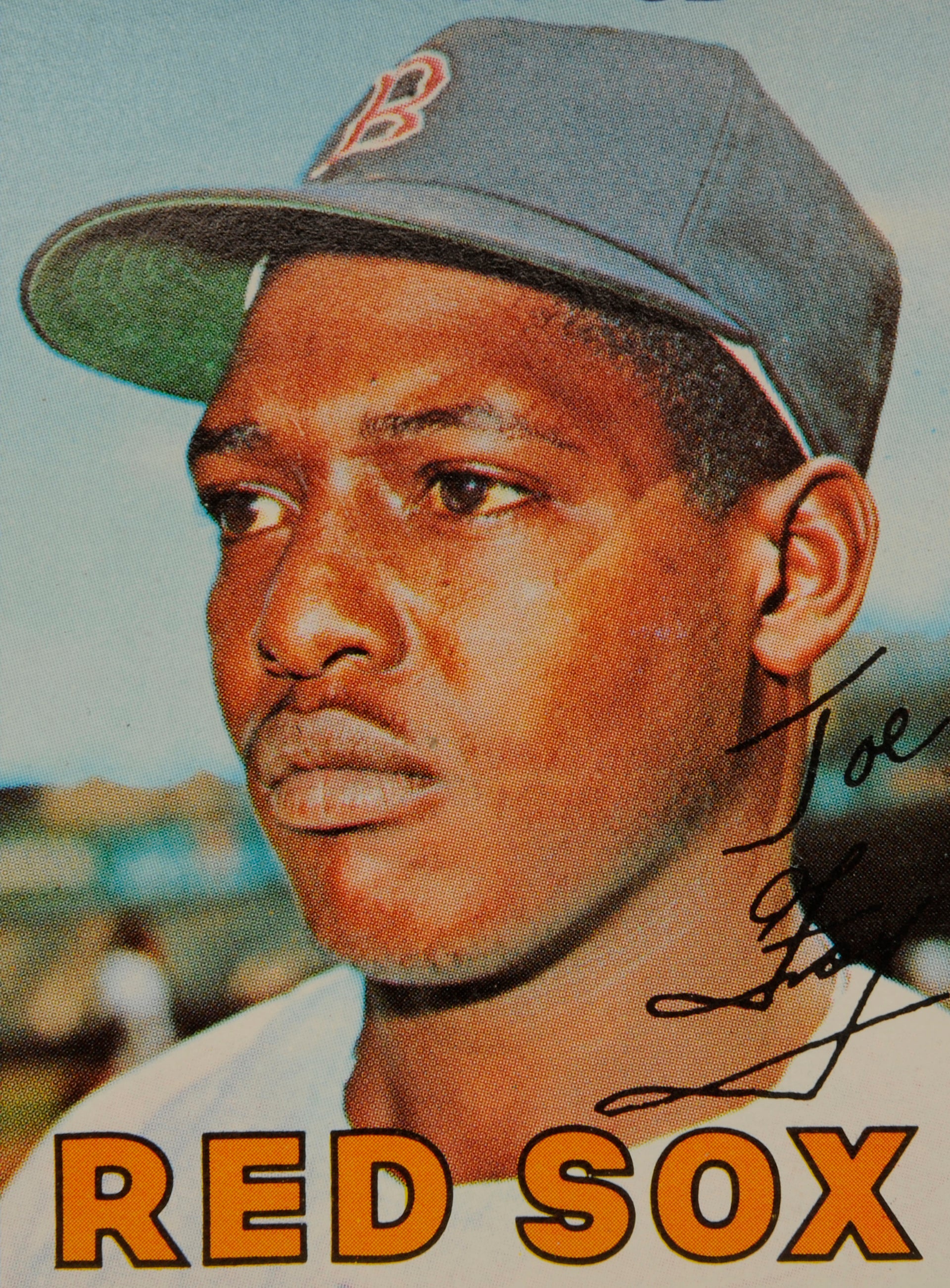

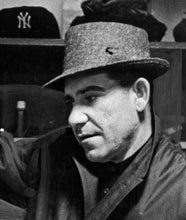

Johnny Blanchard epitomizes that look on his 1966 Topps card. Fittingly, it was the final card that Topps produced for the longtime catcher and outfielder.

Just how “grizzled” is Blanchard on this card? His hair is unkempt, matted down and full of perspiration, an indication that he has just removed his cap or helmet after a healthy workout. There are also a few traces of wrinkling around his eyes and the edges of his mouth; clearly, Johnny is not in his 20s anymore. And his face has that brownish tan, evidence of all those afternoons spent in the sun, either working out or playing in games. After all, there was little that players of this era could do to avoid the effects of the sun. Sunscreen was not as effective as it has become, and teams played more afternoon games in the 1960s than they typically do today.

In spite of his well-worn appearance, Blanchard is no less enthusiastic about the game he has been playing professionally for 15 years. Rarely have I seen a player flashing as wide a smile as Blanchard does here. It’s a sincere smile, too. Old Johnny Blanchard really seems to enjoy his place in the game.

There’s one other notable feature to this card – and this one seems out of place. He is listed as “John” Blanchard by Topps. Growing up and hearing his name on television broadcasts, I don’t ever remember anyone calling him John; it was always “Johnny.” To this day, whenever someone within the game refers to Mr. Blanchard, they call him Johnny, almost without fail.

It was 10 years ago that we lost Blanchard to a heart attack, so it seems like an especially appropriate time to take a deeper look at his career. He was a good player who played key roles on some excellent teams; in fact his teams were perhaps too good, because there were always other catchers around to soak up playing time, leaving Blanchard to play the role of a backup.

Blanchard’s pro career began in 1951, when the New York Yankees signed him as an amateur free agent out of Minneapolis, where he starred in high school. The Yankees thought so highly of the 18-year-old outfield prospect that they gave him an upfront signing bonus of $30,000 and had him skip the lower level of minor league ball. Instead, the Yankees assigned him to Triple-A Kansas City, their top affiliate in the American Association.

In truth, the teenager questioned whether he was ready for the challenges of Triple-A at such a young age. Playing in 14 games for Kansas City, the lefty-hitting Blanchard batted a respectable .268, but without a home run. The Yankees then sent him to Binghamton of the Class A Eastern League, mostly because they had an abundance of outfielders at Kansas City.

Without enough playing time to go around in Triple-A, Blanchard received a chance to play more regularly for Binghamton. But Blanchard struggled so much at Binghamton, enduring an 0-for-29 slump at one point, that he grew anxious and developed an ulcer. He then finished out the season with Amsterdam of the Class C Can-Am League, where he played in the outfield and dabbled in catching, too. Blanchard fared badly at both of those minor league locales, hitting .183 and .206, respectively, for the two affiliates.

In 1952, the Yankees stabilized Blanchard’s situation by having him play the entire season for Joplin, a team in the Class C Western Association. His play improved significantly; he batted .301 with 30 home runs and a .585 slugging percentage. He also made a fulltime conversion to catcher, a position that would likely afford him a faster track toward the major leagues. The transition was not easy, as evidenced by his league-leading 35 passed balls, but Blanchard did his best learning the craft of catching under the tutelage of player/coach Vern Hoscheit.

In all likelihood, the Yankees would have promoted Blanchard to either Class A or Double-A ball in 1953, but real world events created an interruption. The United States Army drafted him, at a time when the country was still involved in the Korean War. Blanchard did not see action in Korea, but was assigned to basic training in California. On his very first day in the military, the camp commander informed all of the new trainees that he didn’t much care for professional athletes, seemingly a way of singling out Blanchard. He endured the experience as best he could before being shipped out to a base in Bavaria, Germany. There he played ball for the 47th Regiment team, which was known as the Raiders.

After concluding his tour with the Army, Blanchard returned to the Yankees and reported to their Spring Training camp in March of 1955. Blanchard spent much of the spring with the Yankees before being assigned to their new Triple-A affiliate, the Denver Bears. He played in only four games for Denver before being sent back to Binghamton, where his manager, George “Snuffy” Stirnweiss, kept careful watch on his developing skills. Stirnweiss was tough on Blanchard, but the approach made the young prospect a better catcher.

At the plate, Blanchard excelled for Binghamton, hitting a league-leading 34 home runs. In September, the Yankees recalled Blanchard so that they would have a third catcher behind Yogi Berra and Elston Howard for the stretch run. Blanchard appeared in one game for the pennant-winning Yankees, going hitless in three at-bats but also coaxing a base on balls.

Given his first taste of the major leagues, Blanchard might have thought he would have a chance to make the Yankees’ roster in 1956. It didn’t happen. He went back to Double-A – and, in fact, he would spend the next three seasons stuck in the minor leagues. In the spring of 1958, he played so well in exhibition games that the Yankees voted him their standout rookie of Spring Training and actually brought him north on Opening Day, before giving him the last-minute news that he was headed back to Denver. Once again, Blanchard proceeded to put up huge offensive numbers for the Bears, but his performance couldn’t convince the Yankees to promote him to the Bronx later that season.

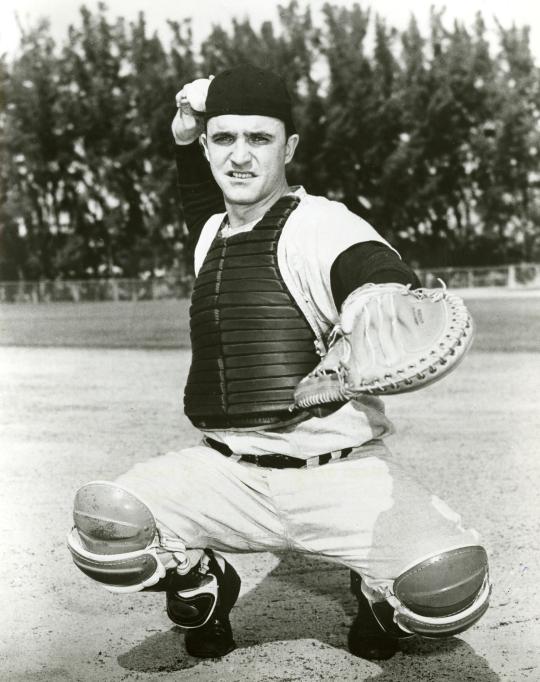

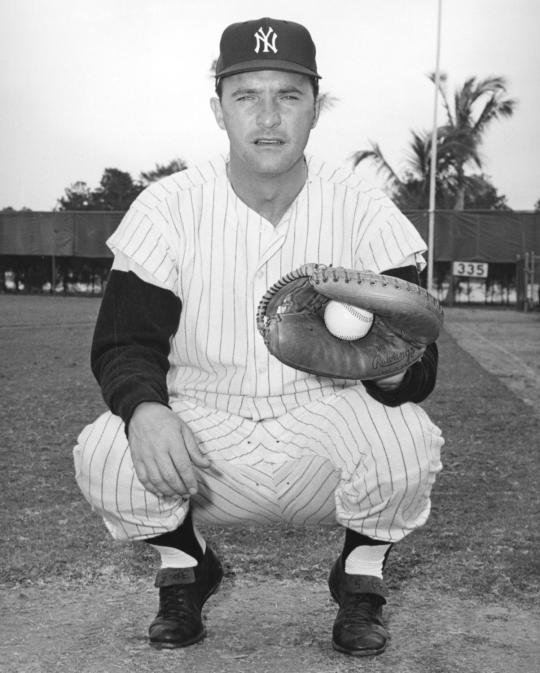

Finally, that all changed in 1959. Blanchard made the Opening Day roster and remained with New York for the entire season. Blanchard backed up Berra and Howard behind the plate, but also saw some time in the outfield and at first base. While Blanchard was thrilled to be in the major leagues, the sporadic playing time made it difficult for him to find his hitting stroke. He received only 59 at-bats in 49 games, accumulating a batting average of just .169.

The situation would improve for Blanchard in 1960. Berra and Howard went down with injuries, creating a need for Blanchard to catch more often. Additionally, manager Casey Stengel became ill, forcing him into a short stay in the hospital. Yankee coach Ralph Houk, who liked Blanchard, became the interim manager and gave his young receiver more playing time.

When Stengel returned, Blanchard’s playing time shrank again. Blanchard’s relationship with his manager remained problematic; Stengel simply didn’t feel confident in Blanchard’s catching abilities. Similarly, Blanchard did not have a good relationship with his general manager, George Weiss.

In the 1960 World Series, Blanchard played exceptionally, hitting .455 in 11 at-bats, but that performance was overshadowed by a disappointing seven-game loss to the Pittsburgh Pirates. After the Series, the Yankees essentially fired Stengel, though they officially announced that he had “retired.” Houk became the fulltime manager.

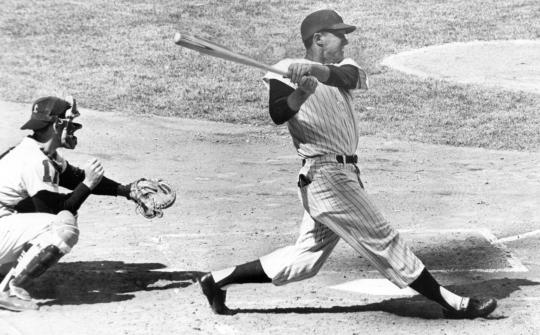

This was the break that Blanchard needed. Houk turned to Blanchard to play a prominent role as a part-time catcher, fill-in outfielder and pinch hitter. With his pull-hitting approach, Blanchard was particularly well suited to Yankee Stadium’s short porch in right field. Appearing in a career-high 93 games, Blanchard blasted 21 home runs, slugged .613 and posted an OPS of .995. During one stretch, he homered in a major league record four consecutive at-bats, stretched out over three games. On most teams, Blanchard would have been the No. 1 catcher. With the Yankees, he emerged as the best bench player in the entire American League, a player known as “Super Sub.”

The Yankees rolled to 109 wins that summer, with Roger Maris and Mickey Mantle making most of the headlines. But without that deep roster, and without a bench headlined by Blanchard, the Yankees would not have been quite as dominant. (Blanchard himself considered the ’61 Yankees the greatest team in the history of the game.)

Blanchard’s contributions only escalated during the World Series against Cincinnati. Appearing in all five games of an impressive rout of the Reds, Blanchard batted .400 with two home runs and two walks. In Game 5, injuries to Berra and Mickey Mantle forced Houk to revise his lineup. For one of the first times in his career, Blanchard batted cleanup; he responded with a home run, a double, and a single, as the Yankees capped off the championship with a 13-5 blowout.

Coming off the best season of his career, Blanchard anticipated even larger responsibility with the 1962 Yankees. He ended up playing in the exact same number of games (93), but his numbers slipped. He hit 13 home runs and batted just .232. The World Series also brought some frustration, as Blanchard struck out in his only at-bat. Still, the Yankees claimed the title, giving Blanchard his second World Series ring.

After the fallback of ’62, trade rumors began to circle around Blanchard. One report indicated that he might be traded to the Philadelphia Phillies for veteran pitcher Art Mahaffey. Like most rumors, the trade never happened, and Blanchard remained in New York, but with a different role. He did not catch a single game, instead playing all of his games in the outfield. He showed more power in ’63, hitting 16 home runs, but his batting average fell to .225. The season also ended in disappointment for the team, with the Yankees losing the World Series to Los Angeles. Blanchard played in one game, coming up hitless in three at-bats.

After the ’63 World Series, the Yankees moved Houk up to the front office to become general manager and hired Berra as his dugout replacement. Berra made sure to return Blanchard to the catching position, while also using him as a first baseman and outfielder. Blanchard batted a more respectable .255, albeit with less power. He then made one appearance in the World Series, which the Yankees lost to the St. Louis Cardinals.

In 1965, Blanchard played for his third manager in three seasons; Berra was fired and replaced by Johnny Keane. Used exclusively as a catcher by Keane, Blanchard struggled at the plate. With his batting average at a low point of .147, the Yankees decided to trade their veteran, sending him to the Kansas City Athletics in a deal for defensive-minded catcher Doc Edwards.

The news left Blanchard in tears. “I never felt so badly in my life,” Blanchard told famed sportswriter Steve Jacobson, reporting for Newsday. “I’ll never feel as badly again.”

Many years later, Blanchard admitted to another writer, Bill Madden, that the trade so affected that it led him to drink more heavily.

Blanchard would soon encounter culture shock with his new team. Prior to his first game in Kansas City, Blanchard took his place behind the plate. Thinking the game was about to begin, Blanchard then heard music in the ballpark and looked out toward center field, where a group of men dressed as court jesters were playing long trumpets. A few moments later, a mule stepped out of one of the outfield gates and began to make its way to home plate. That’s when Blanchard learned that the mule, nicknamed “Charlie O,” was named for the team owner and also served as the team’s mascot. Welcome to the land of Charlie Finley.

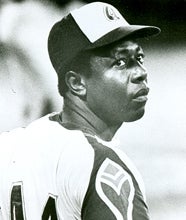

Blanchard lasted only 52 games with the A’s. He didn’t hit, posting an OPS of .517, and was dispatched in September. The A’s sold him to the Milwaukee Braves, for whom he played 10 games. The late-season tenure did produce one memorable moment, with Blanchard having the chance to pinch-hit for the great Henry Aaron.

After the season, Blanchard called it quits. Despite his presence on a 1966 Topps card, he did not play in the major leagues that season. The following winter, he developed a hankering to return to the game. The Braves gave him an invite to Spring Training in 1967. Blanchard hit well that spring and thought he had done enough to at least merit a ticket to Atlanta, the Braves’ top minor league affiliate at the time. Surprisingly, the Braves released him outright, ending his career.

Blanchard returned to his home in Minnesota where he ran a liquor store before becoming a car salesman and then trying his hand in the printing business. During his spare time, he coached a town team in Hamel, a neighborhood of Medina, Minn.

In 2009, the Yankees invited Blanchard, by now retired, to attend Opening Day at Yankee Stadium. Looking forward to a reunion with other former Yankees, Blanchard accepted the invitation. But on March 25, he suffered a heart attack and was rushed to the hospital, where he was pronounced dead. Blanchard was 76.

There seems little doubt that Blanchard loved the game. He could have expressed regrets about being blocked by so many stars on those great Yankee teams, but if he ever did, I haven’t found those complaints. To the contrary, on so many of his Topps cards, and in many photographs, he can be seen sporting a smile. None were any bigger than that smile on his final Topps card in 1966.

Even nearing the end of his career in baseball, grizzled Johnny Blanchard was clearly having a ball.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum