- Home

- Our Stories

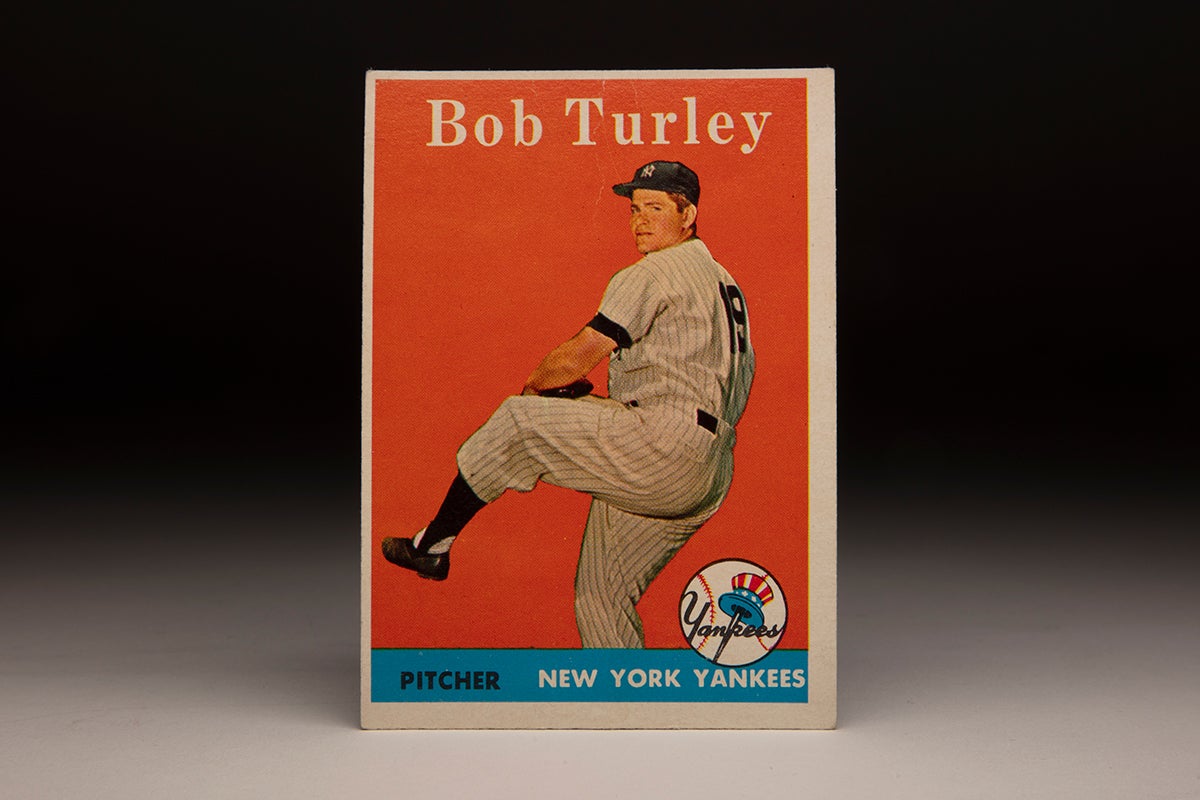

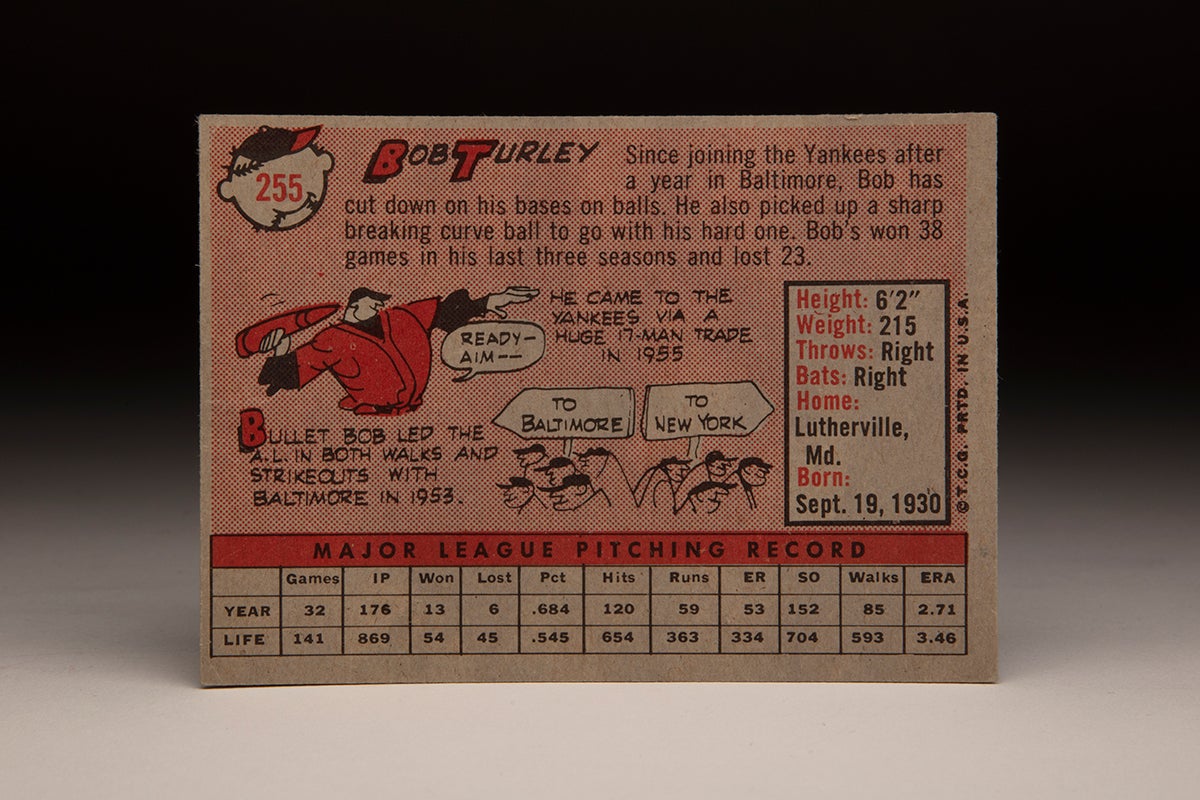

- #CardCorner: 1958 Topps Bob Turley

#CardCorner: 1958 Topps Bob Turley

In the modern era (post 1900), there have been nine seasons in which a pitcher has walked at least 180 batters in one season. Five of those belong to Hall of Fame flamethrowers Nolan Ryan (three) and Bob Feller (two).

Among the authors of the other four seasons, the pitcher with the most name recognition is undoubtedly Bob Turley, who became the first Yankees hurler to win a Cy Young Award just four years after walking 181 batters in a little more than 247 innings.

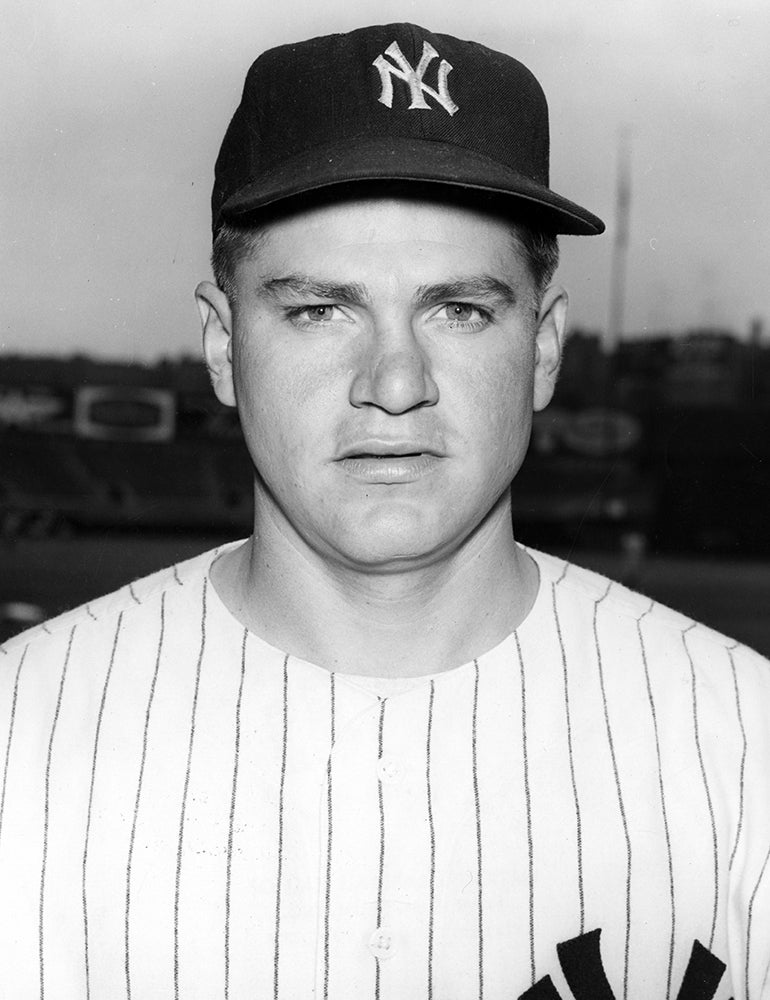

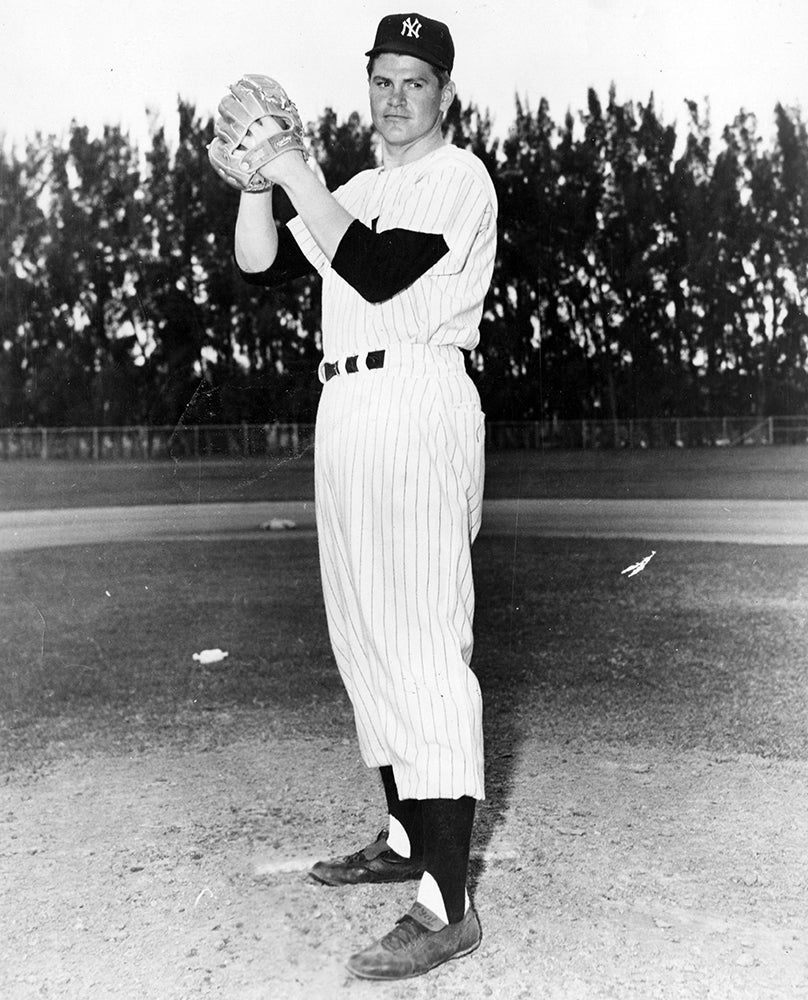

Bullet Bob Turley was indeed a fastball master, with his offerings being timed at between 94 and 98 mph by a DuMont cathode-ray oscilloscope. When that fastball found the strike zone, Turley was nearly unhittable.

Born Sept. 19, 1930, in Troy, Ill., Turley was raised in East St. Louis, Ill. He did not pitch high school ball until his senior year.

“(Central High School coach) Pick Dehner said he had his pitching staff picked,” Turley told the Associated Press in 1955. “He asked me to pitch batting practice and I said: ‘I’m no batting practice pitcher.’”

Dehner quicky agreed.

“He was very fast then and one thing I will always remember about him is that when he first started to pitch for me he was always knocking his cap off his head while taking his windup,” Dehner told the AP. “He wasn’t my first-string pitcher until the last two weeks of the season.”

Honored in high school for his character on and off the field, Turley’s size (he would top out at 6-foot-2 and 215 pounds) and speed brought him notice as he prepared for graduation. But he was not the only member of his family to play baseball: His uncle, Ralph Kress Turley, was two years older than him and also attracting attention from big league scouts.

“(St. Louis Browns general manager) Bill DeWitt asked me to come to Sportsman’s Park in St. Louis for a trial the day before I was to graduate (high school),” Turley told the AP. “Earlier, the Yankees had asked me to report to a tryout camp at Maryville, Ill. My uncle Ralph was also a pitcher (and he) went along. The Yankees liked both of us and suggested we report to an advance camp in Missouri for another look.

“I didn’t go because I wanted to play ball right away. The day after I graduated, (the Browns) signed me.”

Legend has it that the Yankees misidentified the Turleys due to their first names (Robert and Ralph) beginning with the same letter and mistakenly signed Ralph, who was soon released by his team in Belleville, Ill.

“They told me they signed the wrong Turley,” Bob told the AP.

Bob Turley was also sent to Class D Belleville, and in 1948 he went 9-3 with a 4.45 ERA in 16 games. He moved up to Class C Aberdeen of the Northern League in 1949, going 23-5 while striking out 205 batters in 230 innings.

After spending most of the 1950 season with Wichita of the Class A Western League, Turley dominated Double-A hitters at San Antonio in 1951, going 20-8 with a 2.96 ERA. That performance – good for Texas League Most Valuable Player honors – earned him a late-season call-up with the Browns, and Turley made his big league debut on Sept. 29 against the White Sox, taking a one-hitter into the sixth inning but eventually allowing 11 hits and six runs in an 8-3 loss in the team’s next-to-last game of the season.

Eleven days later, Turley enlisted in the Army. He was sent to Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio, Texas, and upon visiting home that winter he broke his right leg after slipping on an icy sidewalk. But once the leg healed, Turley began pitching for the Brooke Army Medical Center team at Fort Sam Houston and honed his craft.

Discharged from the Army in the summer of 1953, Turley joined the Browns on Aug. 17 and made his first big league appearance in almost two years the following day – throwing one inning of shutout relief against the White Sox. He made 10 appearances for St. Louis that season, going 2-6 with a 3.28 ERA and 61 strikeouts over 60.1 innings for a team that lost 100 games.

With owner Bill Veeck facing a bleak financial picture, the American League owners forced Veeck to sell and then allowed the Browns to relocate to Baltimore for the 1954 season.

With many of the same players from the 1953 Browns, the debut version of these Orioles finished with as many losses as the Browns did the year before. But Turley established himself as a budding ace, going 14-15 with a 3.46 ERA over 247.1 innings while striking out 185 batters. He also walked 181 – with both totals leading the major leagues.

“Turley’s got everything,” Orioles catcher Les Moss told The Boston Globe after Turley pitched a two-hitter against the Red Sox on Aug. 7 – a game in which Turley retired Ted Williams in each of his four plate appearances. “If he takes care of himself and studies the game, there’s no reason why he shouldn’t be one of the best.”

Turley also benefited from instruction from Orioles pitching coach Harry Brecheen, who compared Turley to future Hall of Famer Robin Roberts.

“Same type of pitcher,” Brecheen told The Boston Globe. “Naturally, he’s got to work on that change-up. But he’s trying. His curve is good. That and a change, plus the fastball, is all he ever needs.”

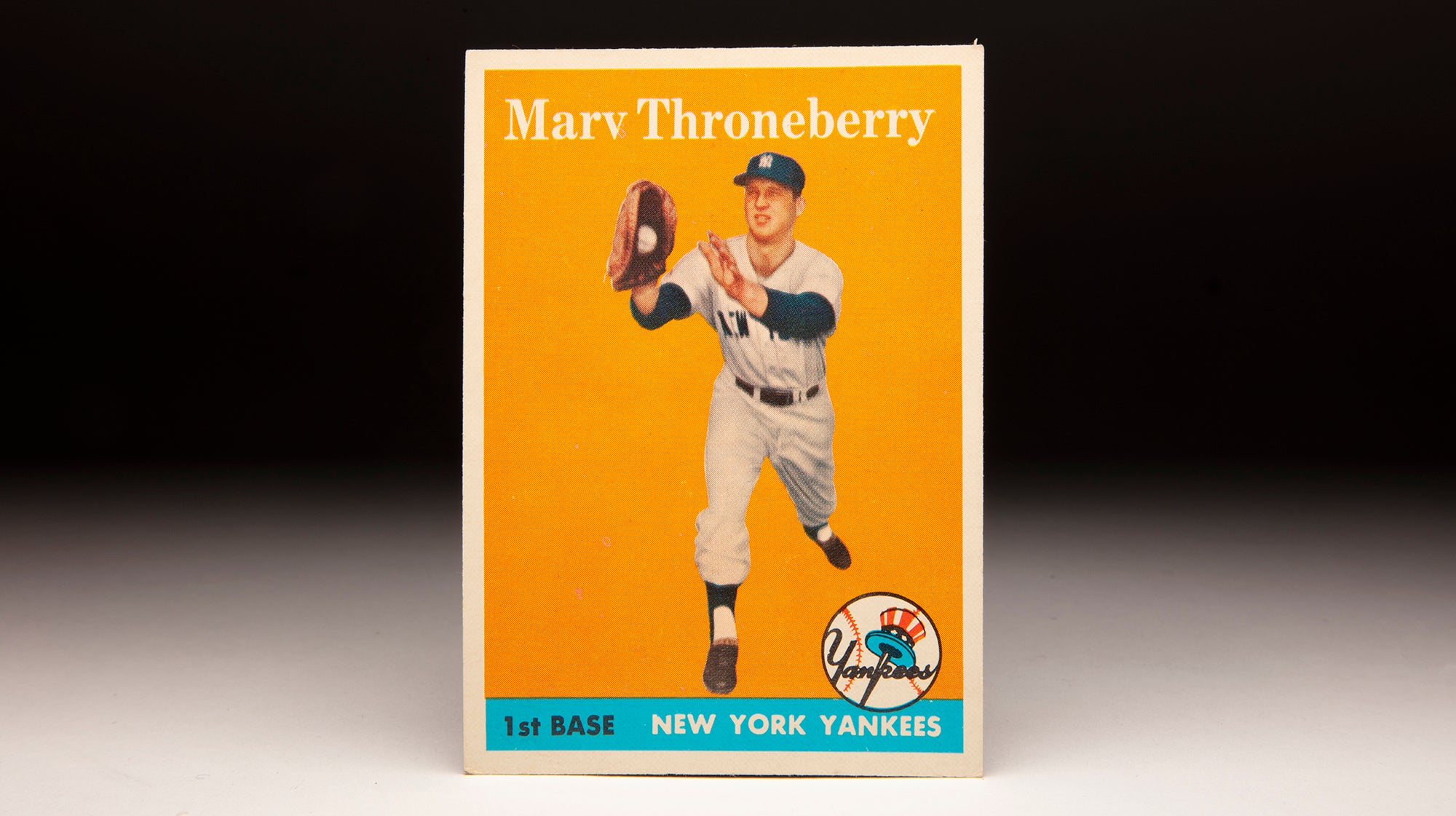

But Turley would not perfect his craft with the Orioles. The Yankees failed to win the American League pennant for the first time in six seasons in 1954, and the team’s front office responded with a 17-player trade – the largest in MLB history – on Nov. 17, 1954. Essentially, the Yankees acquired Turley and Don Larsen to bolster an aging starting rotation.

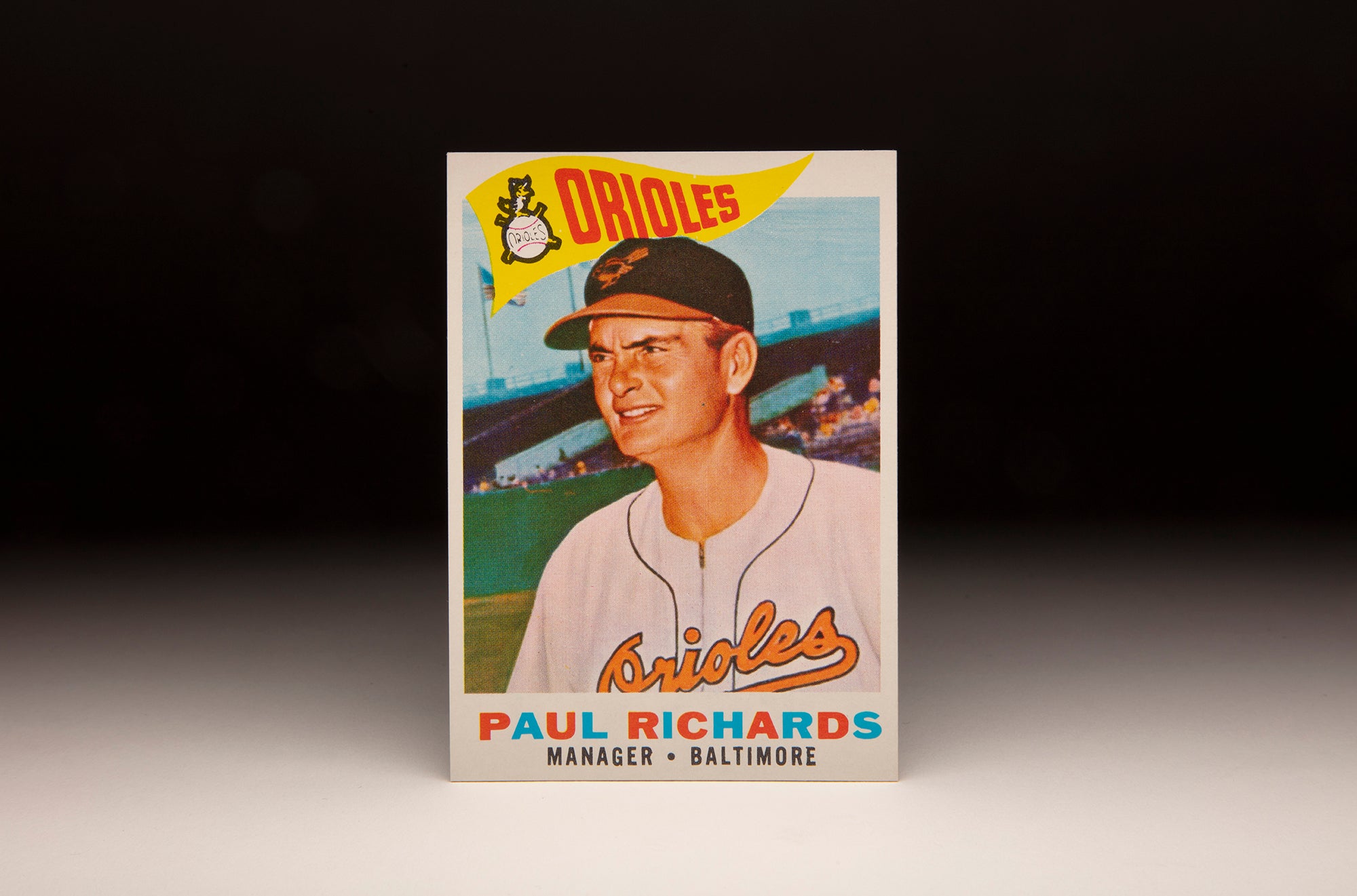

“I knew everyone’s first reaction would be shock,” Orioles general manager Paul Richards, who was hired two months before the trade, told the AP. “You know when you trade off a guy like Turley, who could be a great pitcher, you naturally have misgivings. There’s no use in kidding – it’s tough.

“But if we kept Turley we would have to make up our minds to open next season with the same ballclub. There was no way of improving without putting Turley in the deal. He might win 40 games for the Yanks, but not for us with the club we had.”

The Orioles improved by just three games in 1955 but by 1957 were a .500 club thanks to players they acquired in that deal like Gus Triandos. Turley, meanwhile, turned into the ace the Yankees envisioned, going 17-13 with a 3.06 ERA in 1955 as New York recaptured the AL pennant.

“I don’t know where we’d be without him,” Yankees manager Casey Stengel told the AP during the summer of 1955, “but he’s never had an injury or a sore arm in his life and a fellow who can throw with his speed should be around for a long time.”

Turley again led the AL in walks in 1955 with 177 but also struck out 210 batters and permitted just 6.1 hits per nine innings.

“I haven’t asked him to sacrifice speed for the sake of getting the ball in the strike zone more often,” Stengel said in 1955. “I’ve told him that if he’s going to give walks, he should give them with his best pitch. I never want a pitcher to ease up.”

In his first taste of the postseason, however, Turley struggled. He gave up four runs in 1.1 innings in his Game 3 World Series start against the Dodgers – a must-win game for Brooklyn, which entered the contest having lost the first two games of the series. Turley then pitched in relief in Game 5 and Game 7, allowing one total run over four frames as the Dodgers won the series.

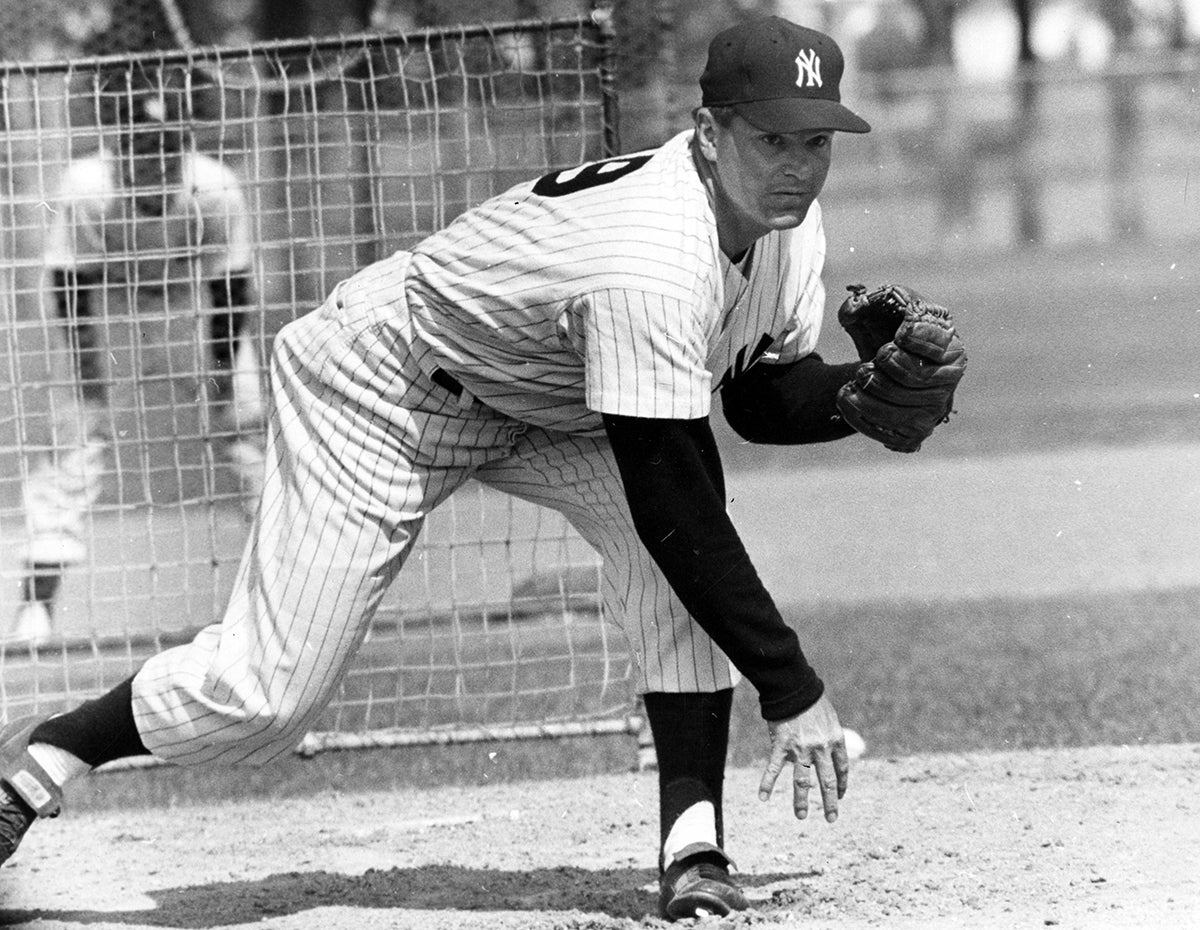

In 1956, Turley’s season was reversed. He struggled in the regular season, going 8-4 with a 5.05 ERA in just 132 innings as Stengel increasingly relied on young starters like Johnny Kucks and Tom Sturdivant. But in the World Series against the Dodgers, Turley regained his confidence with scoreless relief appearances in Games 1 and 2 while employing a new no-windup delivery.

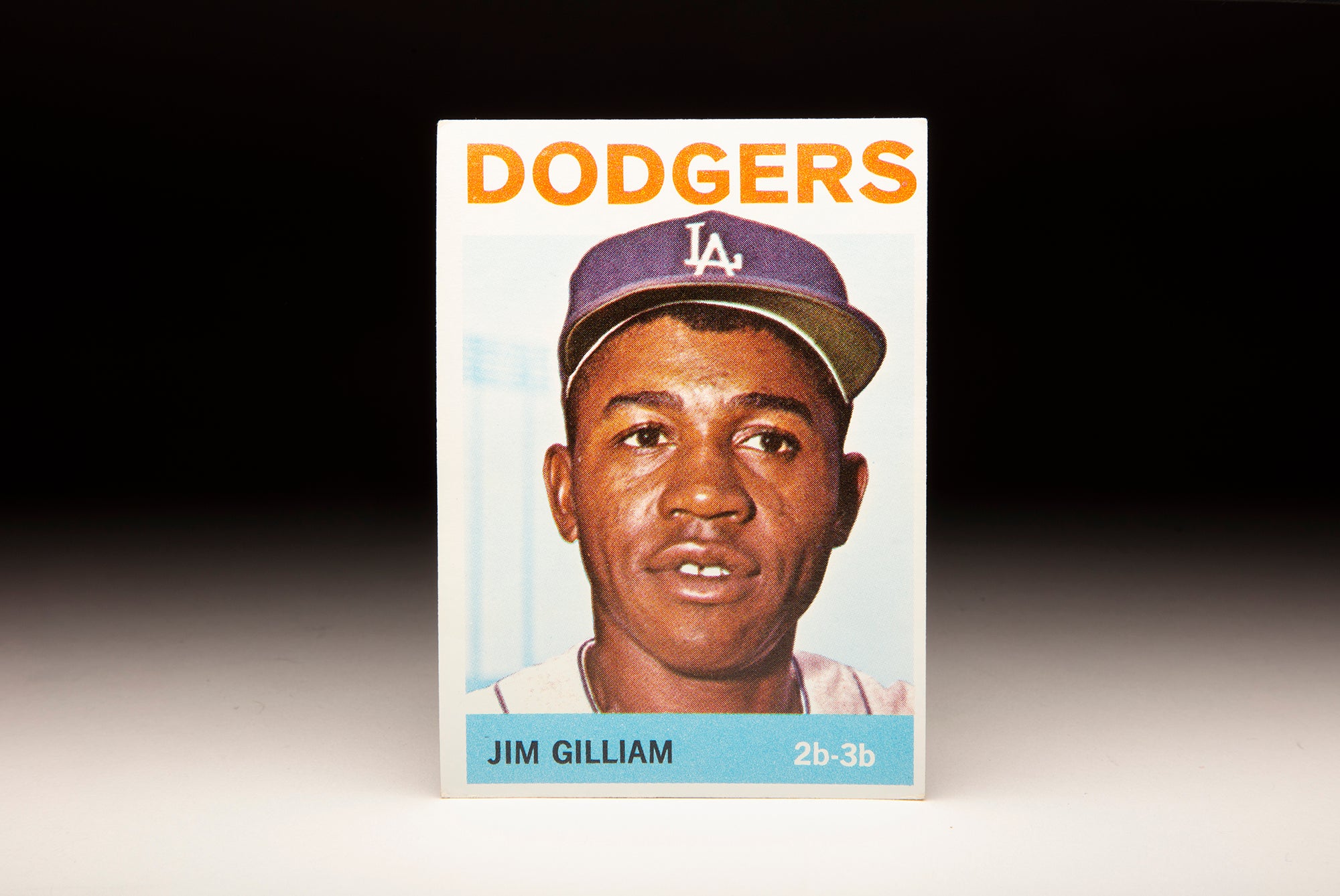

In Game 6 of the World Series, Turley took a hard-luck loss when the Dodgers broke a scoreless tie in the bottom of the 10th inning on a hit by Jackie Robinson that scored Jim Gilliam. Turley struck out 11 over 9.2 innings.

“The most important part of (Game 6) was that it made me believe in myself again,” Turley told the AP after Game 6. “I didn’t know what the matter was with me all season. I thought maybe I had lost my fastball and never would have control. But now I know I’m as good as I ever was.

“I think (a new no wind-up delivery) is the reason I have better control. I first tried it in Boston (in his second-to-last start in the regular season) and then in my two relief appearances in the series. It might be the life saver of my major league career.”

The Yankees ended up winning Game 7 of the 1956 World Series, giving Turley his first World Series ring. He then parlayed his new delivery into a solid 1957 season, going 13-6 with a 2.71 ERA in 176.1 innings. He started Game 3 of the World Series that year against the Braves but did not escape the third inning, allowing one run and leaving with the bases loaded and Hank Aaron coming to the plate. Larsen relieved Turley and got Aaron to fly out – then worked the next seven innings as the Yankees won 12-3 to take a 2-games-to-1 lead in the series.

But the Braves won the next two games, and Stengel turned to Turley to start Game 6. He responded with a four-hitter, striking out eight as New York won 3-2 to force Game 7.

“I wasn’t throwing any ‘bullets’ in the last two or three innings,” Turley told the AP. “(I was) using a sinker mostly with some curves thrown in.”

But Milwaukee won Game 7 5-0 as Larsen was chased from the game in the third inning and Lew Burdette threw a seven-hitter for his third win of the series.

The 1958 season ended in a World Series rematch – but this time Turley was the difference. He went 21-7 with a 2.97 ERA and an AL-best 19 complete games during the regular season, leading the AL in walks with 128 but also permitting just 6.5 hits per nine innings – the fourth time in five years he had led the AL in that ratio category. He started the All-Star Game for the American League.

Turley took the mound in Game 2 of the World Series but could not complete the first inning, allowing four runs in a 13-5 Milwaukee win. But with the Yankees trailing 3-games-to-1 entering Game 5, Turley struck out 10 in a five-hit shutout as New York won 7-0. Turley then picked up the save in Game 6 by retiring pinch-hitter Frank Torre with men on first and third and the Yankees clinging to a 4-3 lead.

In Game 7 the following day, Turley relieved Larsen with the Yankees leading 2-1 in the third inning. He allowed Del Crandall’s sixth-inning home run as the Braves tied the game at 2 – but outdueled Burdette the rest of the way as the Yankees scored four in the eighth inning in what became a 6-2 victory.

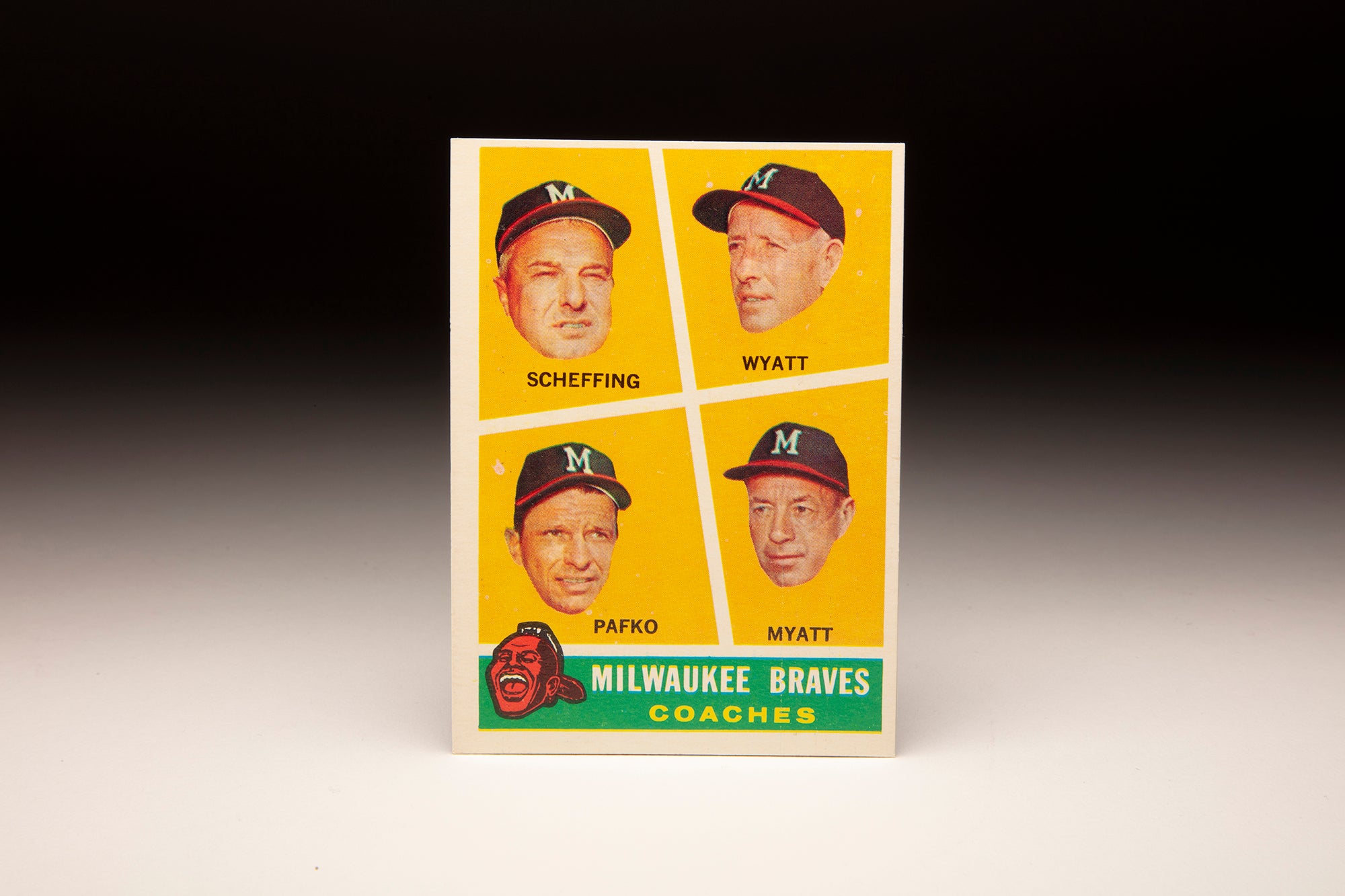

“I can’t say the Yankee pitching is any better than expected – we just weren’t hitting,” Braves pitching coach Whitlow Wyatt told the Chattanooga Daily Times after Game 7. “Turley did not have as good stuff as (Game 5). Not as fast. But (he) was as good as he had to be.”

Turley emerged from the Cy Young Award voting to win by one vote in an era where only first-place votes were counted and only one Cy Young was presented for both leagues. Turley received five votes compared to four for Milwaukee’s Warren Spahn and three apiece for Burdette and Pittsburgh’s Bob Friend.

Turley finished second in the AL Most Valuable Player voting, 42 points shy of winner Jackie Jensen of the Red Sox. Turley also took home the Hickok Belt, awarded to the top pro athlete of the year in the United States.

He credited his heroics to his pitching coaches with the Orioles and Yankees: Harry Brecheen and Jim Turner.

“Brecheen taught me how to live like a big leaguer,” Turley told United Press International after winning the Cy Young Award, “and Turner taught me how to pitch like one.”

After a bit of negotiating, Turley and the Yankees agreed on a 1959 contract worth $32,000, a $7,000 raise from the year before.

“I got exactly what I wanted,” Turley told UPI.

But Turley’s days as an ace were coming to a close. He went 8-11 with a 4.32 ERA in 1959 as the Yankees failed to win the pennant for the first time in four years. In 1960, Turley was 9-3 with a 3.27 ERA in a swingman role, working in 10 games out of the bullpen and recording just 87 strikeouts in 173.1 innings. He pitched two games in the World Series against the Pirates, winning Game 2 despite allowing 13 hits over 8.1 innings as New York powered its way to a 16-3 win. Then in Game 7, Stengel turned to Turley again after a much-questioned strategy where he pitched ace Whitey Ford in Games 3 and 6, making him unavailable the deciding contest. Turley allowed two runs in the top of the first on a home run by Rocky Nelson, then allowed a single to Smoky Burgess to start the second inning – causing Stengel to bring in Bill Stafford. Turley was eventually charged with another run as the Pirates took a 4-0 lead. New York rallied to take the lead in the middle innings before Bill Mazeroski’s home run won it for Pittsburgh in the ninth.

It would be the last of 15 postseason games of Turley’s career.

Turley did receive World Series rings in both 1961 and 1962 as the Yankees won their fourth championship in Turley’s eight seasons. But arm woes limited Turley to just 141 combined innings in those two campaigns – and he underwent surgery in 1961 to remove bone chips from his elbow.

On Oct. 29, 1962, the Yankees sold Turley’s contract to the Angels.

He notched his 100th big league victory on June 12, 1963, with a one-hit shutout over the White Sox but was 2-7 with a 3.30 ERA in July when the Angels released him. He was immediately picked up by the Red Sox, and he went 1-4 in Boston to finish the year with a 3-11 record.

The Red Sox released Turley following the season. He spent the 1964 season as a Red Sox coach before attempting a comeback with Houston – whose general manager was former Orioles skipper and GM Paul Richards. Turley made some appearances in Spring Training but ultimately decided to retire.

He soon ventured into the insurance business and other financial services. Turley passed away on March 30, 2013.

Finishing his career with a 101-85 record and 3.64 ERA, Turley carved out a spot as a Yankees hero. And though he walked almost as many hitters (1,068) as he struck out (1,265), Turley lived up to his “Bullet Bob” nickname for 12 big league seasons.

“Man, when you see me take three swings at three fastballs and not even foul tip one, the fellow throwing ’em must have something,” Dodgers catcher Roy Campanella said after Game 6 of the 1956 World Series when Turley struck out 11 batters. “Maybe he was using a little gun to fire that ball up there.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum