- Home

- Our Stories

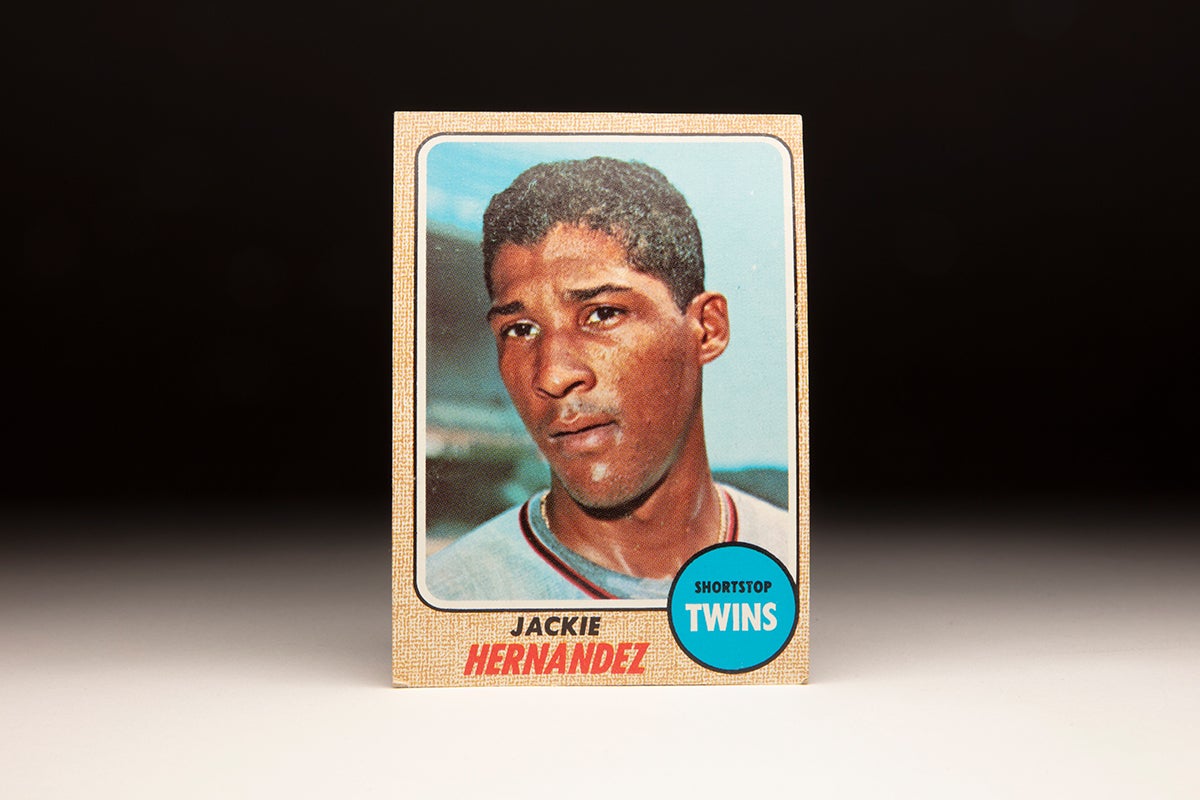

- #CardCorner: 1968 Topps Jackie Hernández

#CardCorner: 1968 Topps Jackie Hernández

In a seven-week span late in the 1971 season, Jackie Hernández twice carved his name into baseball’s permanent record.

Perhaps no other .208 career hitter left a bigger mark on the game. But for Hernández, it was the product of living the life he loved in baseball.

Jacinto Hernández Zulueta was born Sept. 11, 1940, in Central Tinguaro, Cuba, in the Matanzas province. His father, Tomás, worked for a sugar cane mill as a fireman on the railroad that serviced the mill.

Tomás died when Jacinto was 11, with three of the nine Hernández children still at home.

“We lived all right. Nothing big, but all right,” Hernández told the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette in 1971. “My brothers played amateur baseball. I was the second youngest. I got to play when I was 13 or 14 and I kept at it.”

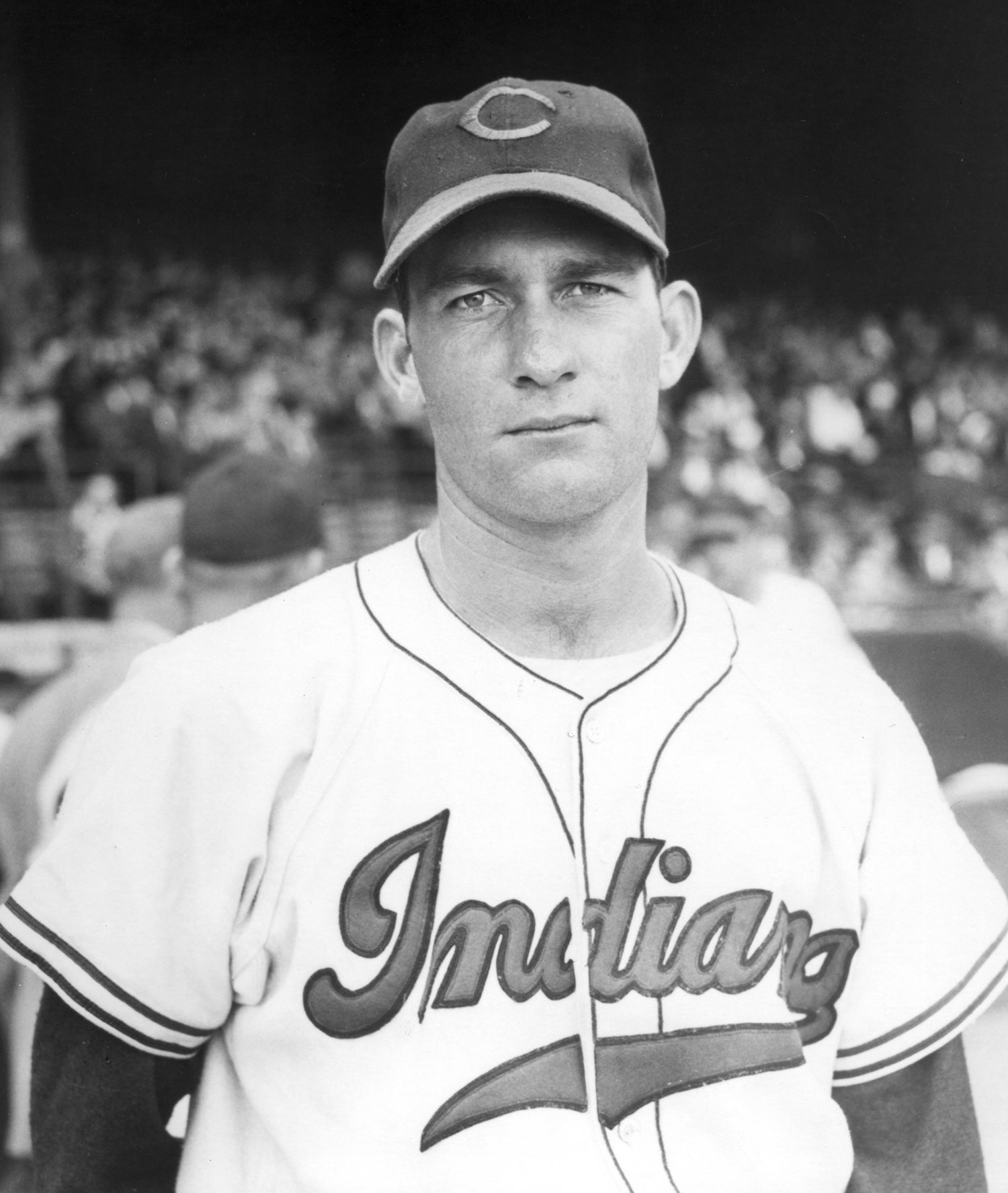

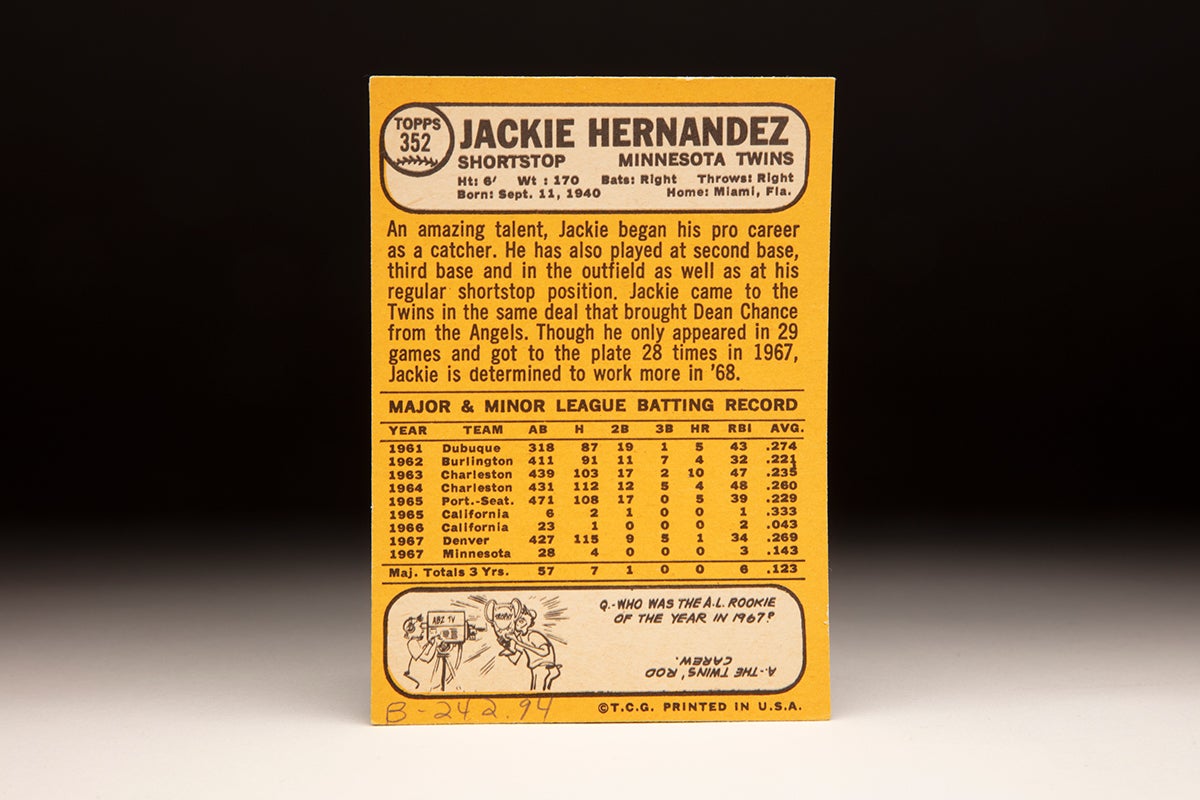

Originally a catcher, Hernández signed with the Cleveland Indians in 1960 for a bonus of 700 pesos (about $200 dollars) and obtained a visa to go to Mexico, and from there he went to the Indians’ Spring Training home in Tucson, Ariz., in 1961.

“There was a language problem for a while,” Hernández told the Post-Gazette. “I ate chicken for three weeks because I didn’t know how to say anything else when I ordered in a restaurant.”

Hernández knew that he would likely never be allowed to return to Cuba under the Castro regime. But he decided that his future was in baseball.

The Indians sent Hernández to Dubuque of the Class D Midwest League, where he hit .274 in 108 games – 95 of which came as a catcher. He moved up to Class B Burlington in 1962, hitting .221 in 125 games. But the Indians transitioned him from catcher to shortstop that season, and Hernández accepted 453 chances in just 88 games at short.

“I like to move around, so I got a glove and went out to short and caught ground balls (in Spring Training),” Hernández told the Kansas City Star in the spring of 1969. “(Coach) Hoot Evers told me I should work at short as much as possible. He didn’t think I could hit good enough to be a catcher.”

Also in 1962, Hernández moved to Miami and a year later married his wife, Ida, who was a United States citizen.

Hernández spent the 1963 and 1964 seasons with Double-A Charleston of the Eastern League. As he did with Burlington, Hernández played about a fifth of his games at catcher and the rest at shortstop with Charleston. He hit .235 in 1963 and .260 a year later, topping the 20-stolen base mark in each year.

In 1965, the Indians assigned Hernández to Triple-A Portland. But a contract dispute prompted Cleveland to cut ties with him and he immediately signed with the Angels as a free agent.

Sent to Triple-A Seattle, Hernández was quickly inserted into the lineup at shortstop by manager Bob Lemon. He hit .229 in 121 games and totaled 24 stolen bases for Portland and Seattle combined while accepting 657 chances at short. He also committed 42 errors – his third straight season with 40-plus miscues – but showed enough range to be considered a prospect while being voted having the best arm among shortstops in the Pacific Coast League.

The Angels promoted Hernández to the big leagues in September, and he appeared in six games down the stretch, recording his first big league hit off Baltimore’s Wally Bunker on Sept. 24.

The Angels kept Hernández on the big league roster as a reserve for the entire 1966 season, but more than half of his 58 appearances came as a pinch-runner. He had one hit in 23 at-bats (.043 batting average).

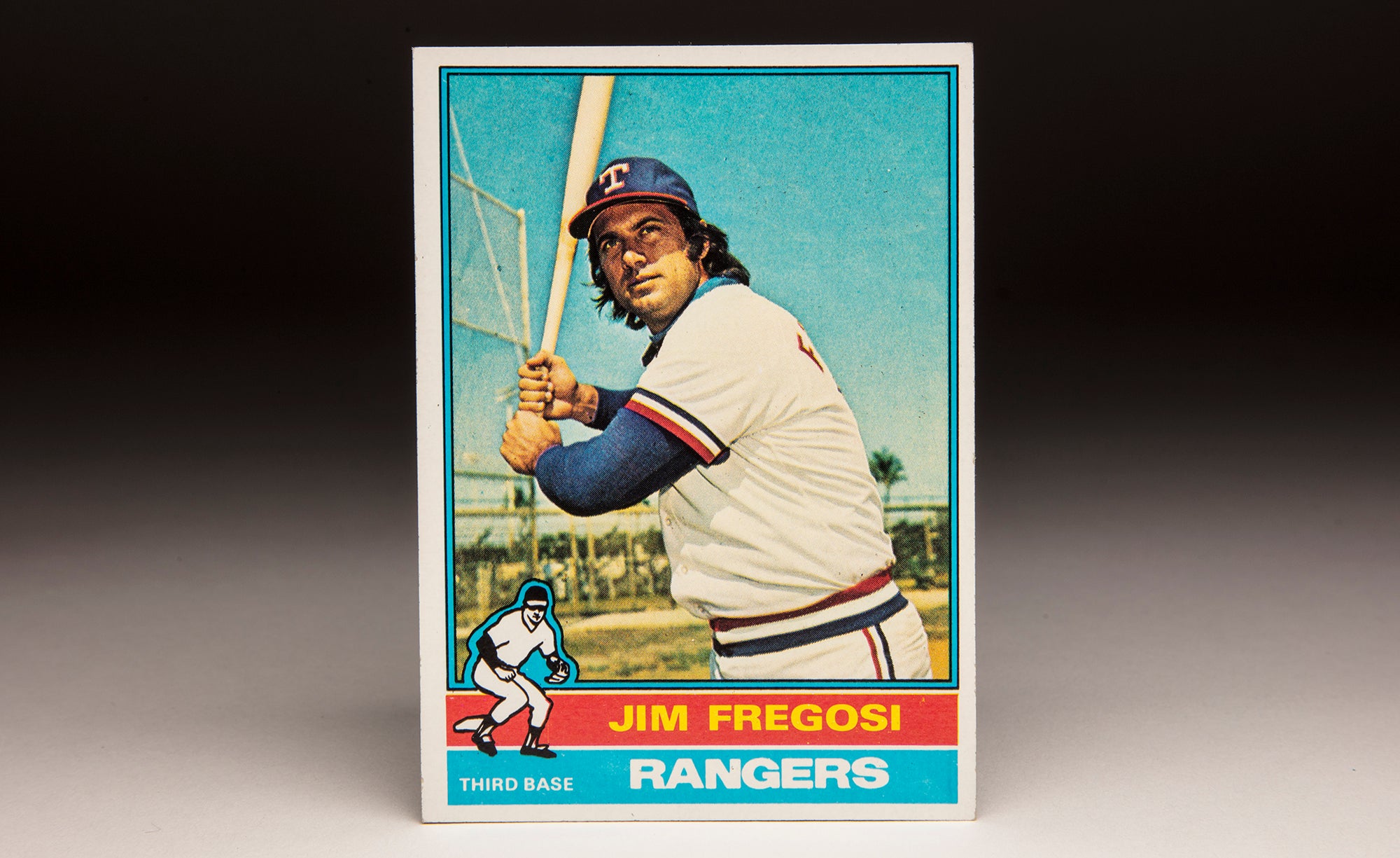

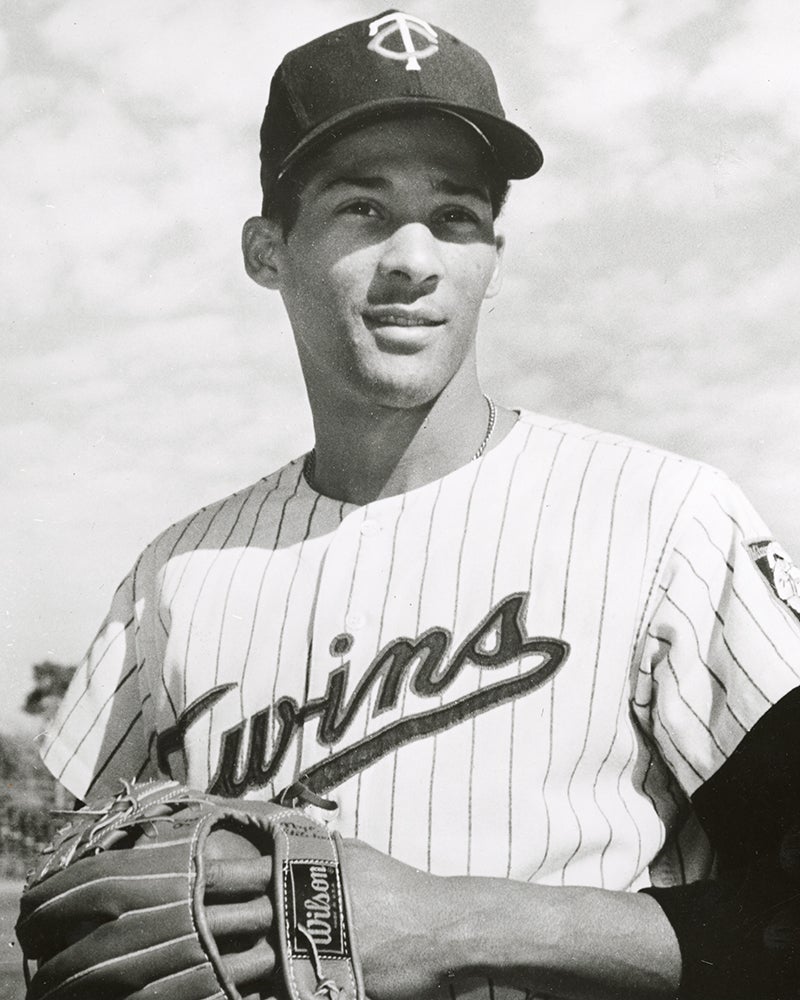

With durable young All-Star Jim Fregosi ahead of him at shortstop, Hernández had little chance of playing regularly for the Angels. On April 10, 1967, the Angels sent Hernández to the Twins to complete a Dec. 2, 1966, deal that brought Pete Cimino, Jimmie Hall and Don Mincher to Minnesota in exchange for Dean Chance.

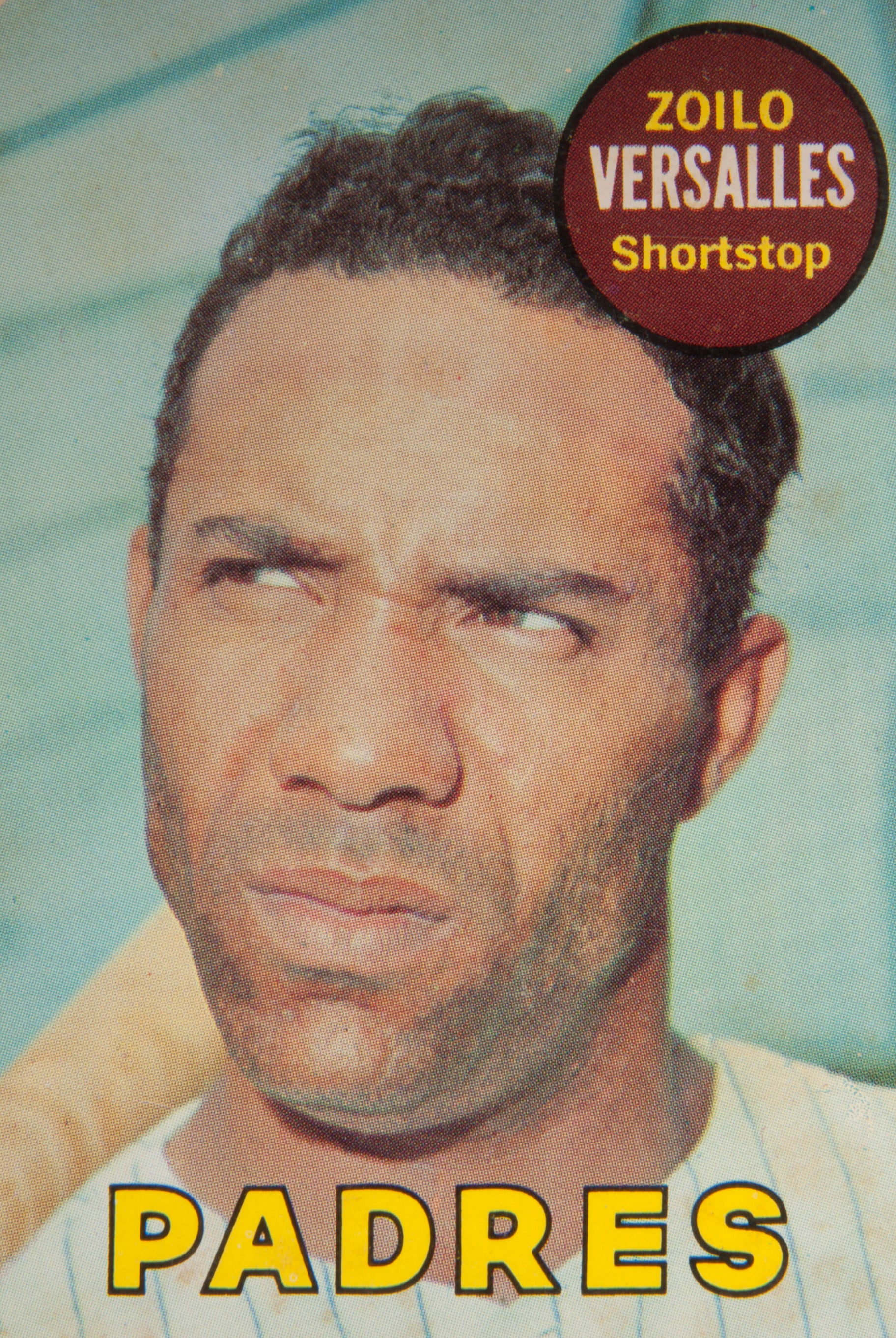

But the Twins already had former AL Most Valuable Player Zoilo Versalles at shortstop, and Hernández was sent to Triple-A Denver. In 112 games with the Bears, Hernández hit .269 and cut his errors to 31 while accepting 640 chances.

In early August – with rookie sensation Rod Carew away from the team with the Marines – the Twins brought Hernández to Minnesota. In his seventh game with the Twins, Hernández helped Minnesota beat his old team when he singled home Hank Izquierdo in the eighth inning to tie the game at 1 and then scored on a Ted Uhlaender double with the deciding run in a 2-1 win over the Angels.

“I knew that if I waited long enough,” Angels manager Bill Rigney sarcastically told the Independent of Long Beach, Calif., “that I’d see Hernández get a hit.”

Hernández stayed with the Twins the rest of the season and finished with four hits in 28 at-bats for a .143 average. Then on Nov. 28, 1967, the Twins traded Versalles and pitcher Mudcat Grant to the Dodgers in exchange for Bob Miller, Ron Perranoski and John Roseboro.

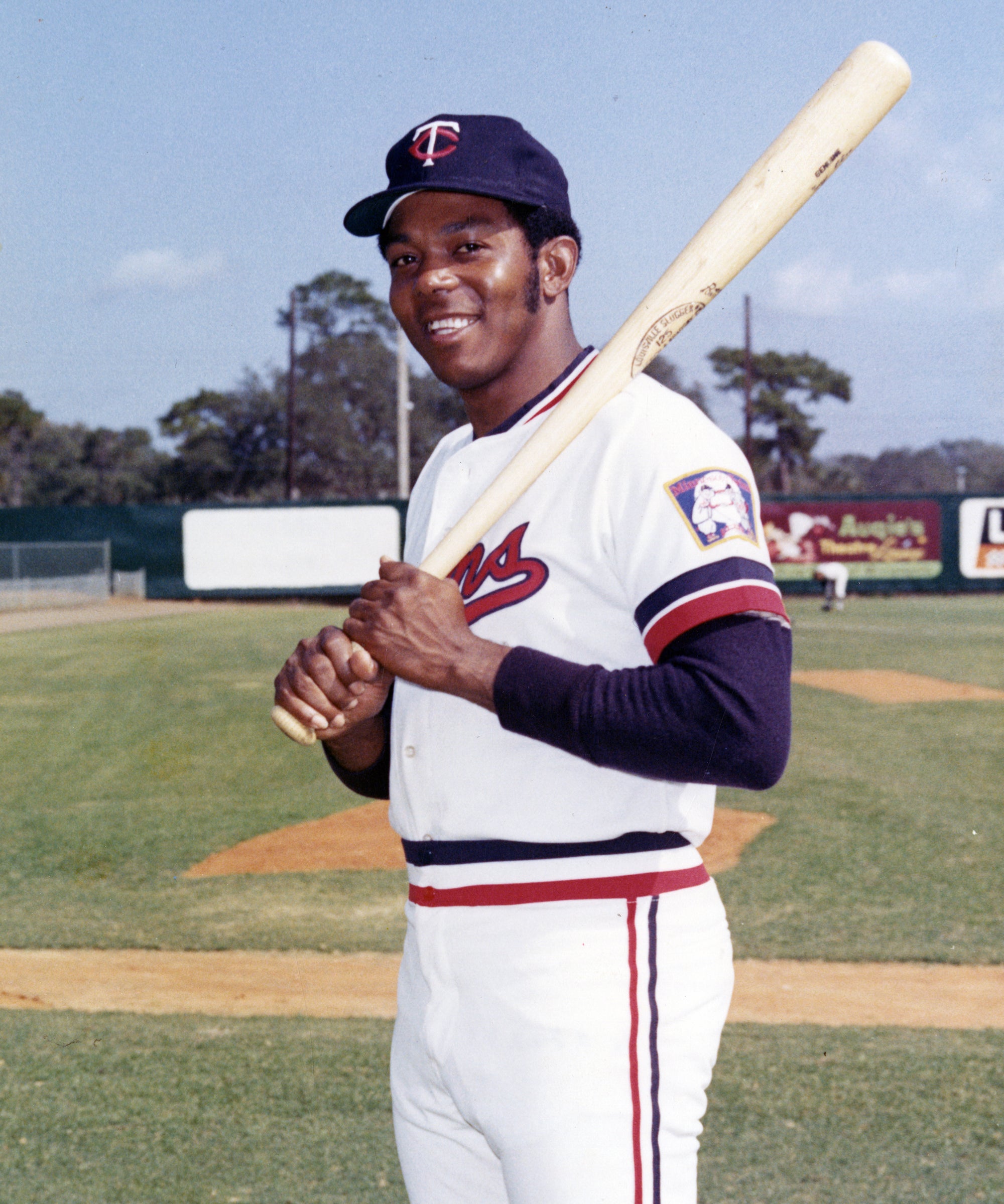

Hernández beat out youngster Rick Renick for the Opening Day shortstop job – a battle that went down to the final days of Spring Training.

“He can do it all in the field,” Twins manager Cal Ermer told the Orlando Sentinel about Hernández. “And if he can get a base hit here and there, we’ll be all right.”

Hernández, who was given the good news by teammates Tony Oliva and César Tovar, was confident he could handle the job.

“I’m going to give it all I’ve got,” Hernández told the Sentinel.

But by the end of June, Hernández was batting .166 through 64 games. The Twins brought Renick back from the minors in mid-July and put him at shortstop, and Hernández was sent back to Denver. He returned to the Twins in September and finished the year batting .176 in 83 games – with 25 errors in 341 chances at shortstop.

The Twins then left Hernández unprotected in the expansion draft, and Kansas City claimed Hernández with the 43rd overall pick.

“What really hurt me was everybody thought we would have one of the top teams,” Hernández told the Kansas City Star about the 1968 season. “People talked about us winning the pennant. They usually said we could win if I did the job at shortstop. When things started to go wrong with the club (Minnesota finished 79-83), things started to go wrong with me.”

From Day 1 in Spring Training of 1969, however, Hernández had the inside track to the starting shortstop position on the first-ever Royals team.

“Things seem different this time,” Hernández told the Star about his place on the roster. “I’ve got something I didn’t have last year: Confidence. And if you don’t have it, you can’t play. If I can relax here like I did (in the minors), I’m OK.”

With glowing recommendations from managers like Billy Martin and Johnny Goryl, Hernández earned the confidence of Royals manager Joe Gordon. He started on Opening Day and was rarely out of the lineup all year, appearing in 145 games while batting .222 with 54 runs scored, 40 RBI and 17 steals. He also committed a big league-leading 33 errors and struck out 111 times, trailing only Reggie Jackson among AL batters in that category.

Hernández was again the Royals’ Opening Day shortstop in 1970 but started only three times from Aug. 1 through the end of the season. He batted .231 over 83 games.

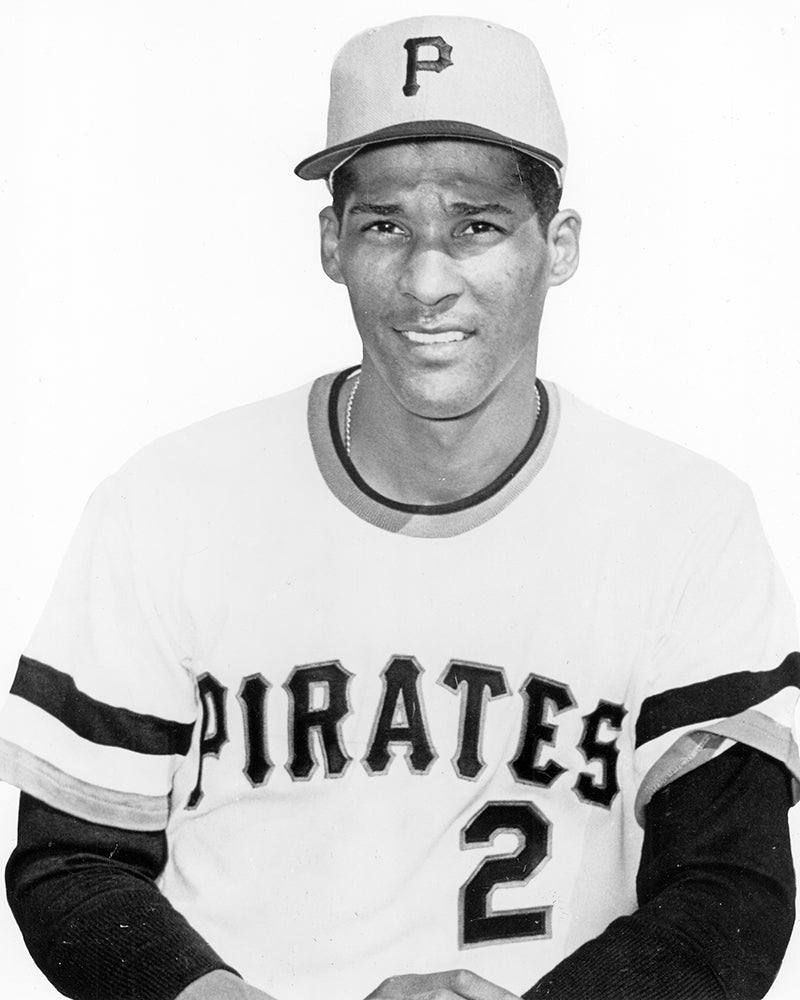

With the Royals entering the offseason looking to replace Hernández, the Pirates and Kansas City made a deal on Dec. 2, 1970, that sent Freddie Patek, Bruce Dal Canton and Jerry May to the Royals in exchange for Hernández, Jim Campanis and Bob Johnson.

Patek would anchor the Royals’ infield for the next decade. Hernández, on the other hand, would help bring the Pirates a World Series title in 1971.

Longtime Pirates shortstop Gene Alley, a two-time Gold Glove Award winner, broke his left hand in Spring Training in 1971, giving Hernández a chance to play regularly. Hernández started on Opening Day and hit safely in his first eight games before Alley reclaimed his job in mid-April.

“I’d like to make something clear,” Pirates manager Danny Murtaugh told the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette in Spring Training when Alley was injured. “Until Alley returns, Jackie Hernández is the No. 1 shortstop.”

After Alley returned, Hernández filled a bench role. But Alley struggled at the plate for most of the season and Hernández saw regular playing time. It was not an easy transition, however.

After committing an error that cost the Pirates a game, a despondent Hernández questioned whether he should be in the big leagues. Pirates superstar Roberto Clemente intervened.

“You’re here with us, that makes you a big leaguer,” Clemente told Hernández. “You want to play, which is the big thing. You are our shortstop, and you will help us win it all this year.

“Don’t worry: You’re a big leaguer.”

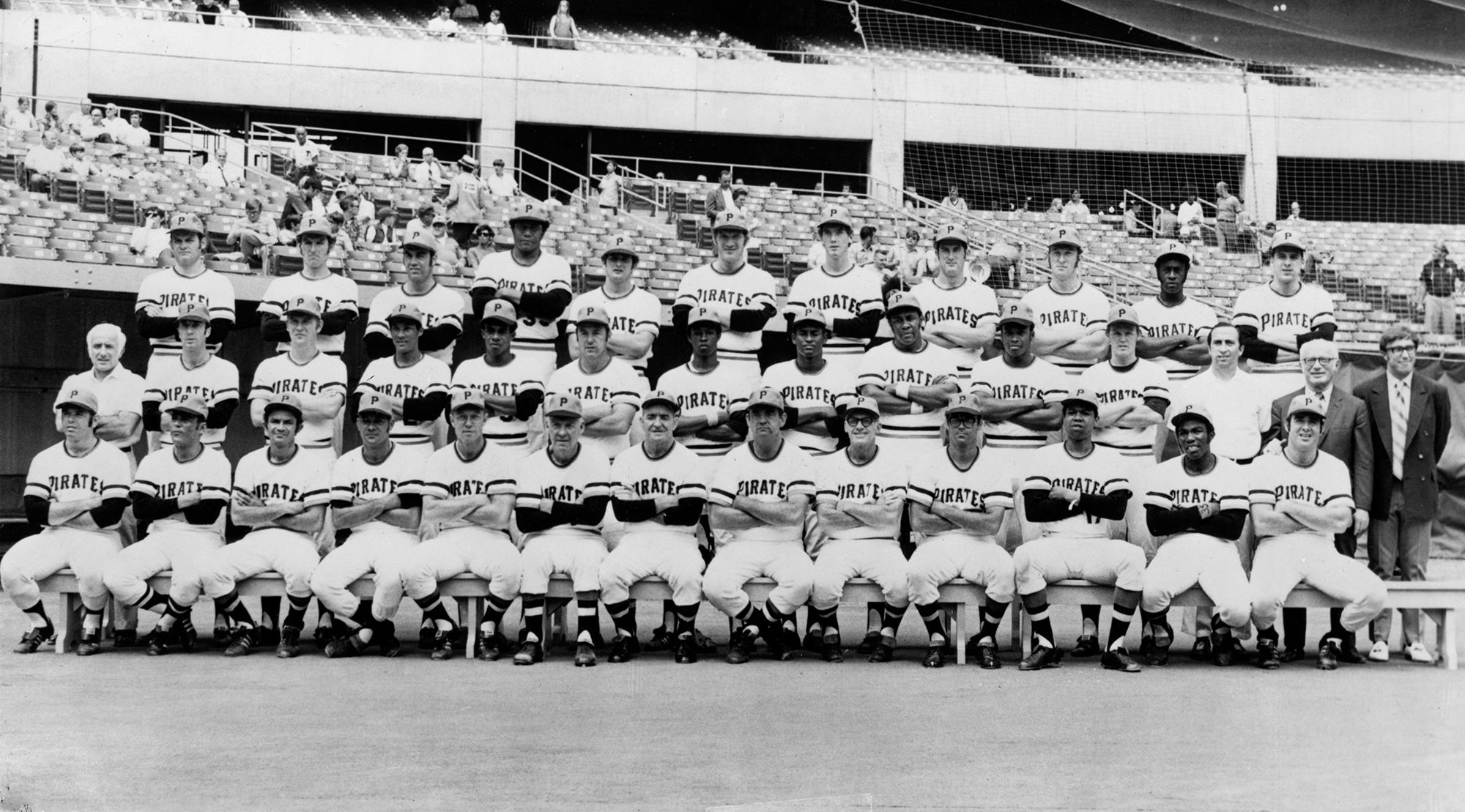

Then on Sept. 1, Hernández helped make history. The Pirates fielded the first all-Black lineup in AL or NL annals that day against the Phillies, with Hernández starting at shortstop.

The Pirates won the game 10-7, and Hernández had an RBI, a walk and a run scored.

“The thing I remember about it, when he was interviewed afterwards, Murtaugh said, ‘I put the nine best athletes out there,’” Pirates pitcher Steve Blass recalled. “The best nine I put out there tonight happened to be Black. No big deal. Next question.’”

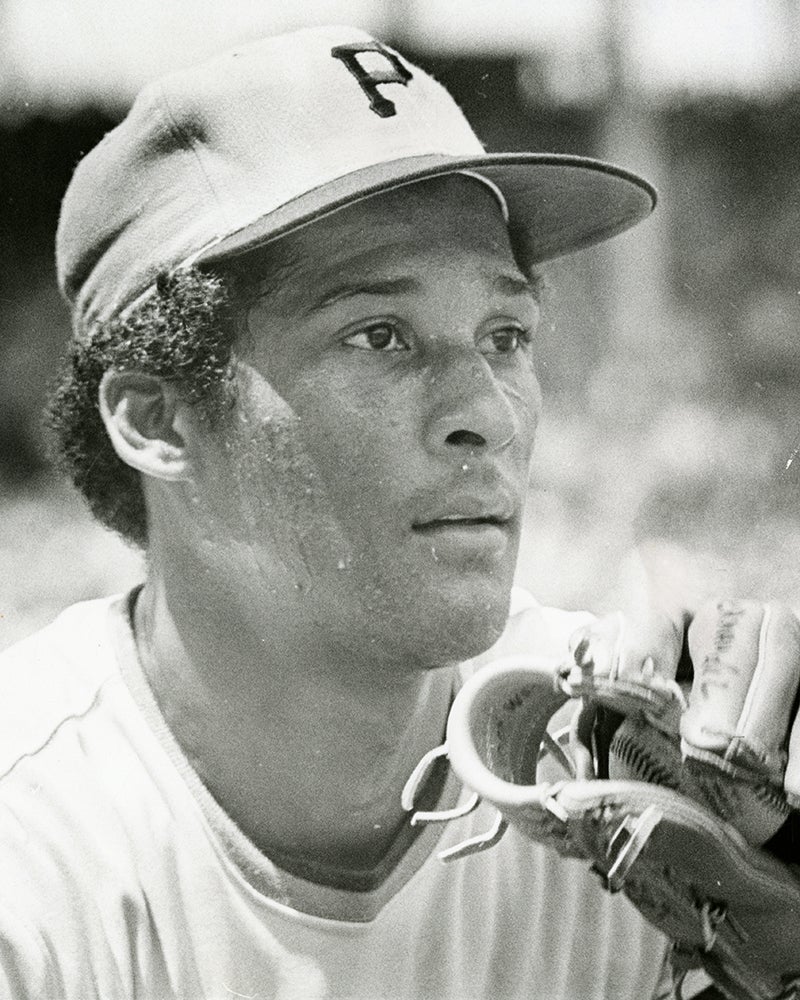

The Pirates won the NL East for the second straight year and advanced to the NLCS vs. the Giants. Hernández started all four games at shortstop, collecting three hits and an RBI while committing just one error as Pittsburgh advanced to the World Series.

Waiting to meet the Pirates were the Orioles. In an oft-repeated quote that spring, Baltimore manager Earl Weaver reportedly said: “Jackie Hernández is not a winner” when he was told that Hernández would be the Pirates’ Opening Day shortstop.

Hernández started six of the seven games in the World Series (Alley started Game 3), collecting four hits and two walks while scoring two runs. He did not commit an error.

With two outs in the bottom of the ninth inning of Game 7 and the Pirates leading 2-1, Hernández ranged to his left on the Memorial Stadium infield, grabbed a high hopper off the bat of Merv Rettenmund deep behind second base and fired to first baseman Bob Robertson to record the final out and give Pittsburgh the title.

In 88 games in 1971, Hernández hit .206 with 26 RBI. But his play in the postseason convinced the Pirates they did not need to look for another shortstop – even with Alley’s knee bothering him in Spring Training in 1972.

“We believe Hernández can play major league shortstop,” Pirates general manager Joe Brown told the Associated Press. “He certainly showed that in the World Series. If Alley’s knee comes back (after surgery), we have the best shortstop in the league. Even if he doesn’t, Hernández is more than adequate.”

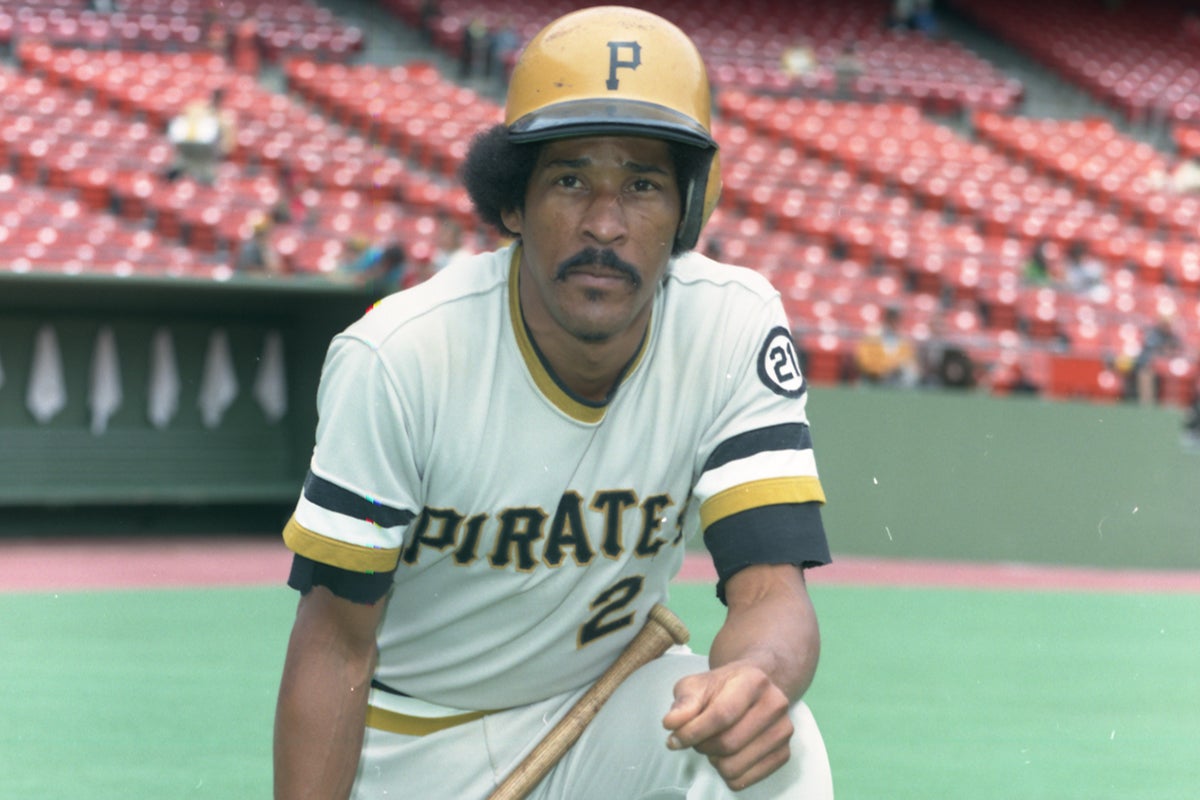

Hernández made his fifth straight Opening Day start at shortstop in 1972 and was widely popular with the media and his teammates after his performance in 1971. But he struggled on a personal level with not being able to see his family in Cuba.

“Sometimes I get depressed,” Hernández told the Post-Gazette about not being able to return to Cuba to see his mother. “I try to wipe things out of my mind, but it’s difficult. Since I’ve been gone, there have been 24 new nieces and nephews. My mother sends me pictures of them. The pictures help, but just once I’d like to see my mother, my brothers, sisters…everybody.”

Hernández and Alley shared shortstop duties for the Pirates in 1972, with Hernández batting .188 over 72 games – though the Pirates were 38-19 when he started. Pittsburgh again won the NL East, but manager Bill Virdon – who replaced Murtaugh when Murtaugh retired following the 1971 World Series – started Alley in all five games of the NLCS vs. the Reds. Alley went hitless in 16 at-bats as Cincinnati advanced to the World Series.

Hernández did not appear in any of the games.

Alley and Hernández again were slated to share shortstop duties for Pittsburgh in 1973, and Alley got the Opening Day assignment. But the Pirates grew dissatisfied with the arrangement and acquired veteran Dal Maxvill from the Athletics on July 7. Maxvill immediately assumed the starting role at shortstop, and between July 10 and Aug. 30, Hernández came to the plate only two times.

But with Maxvill nursing a sore elbow, Virdon turned to Hernández in an Aug. 31 doubleheader against the Cubs. Hernández went 2-for-6 with a triple and two runs scored as the Pirates swept the twinbill.

“You’ve got to give Hernández credit,” Virdon told the Pittsburgh Press after the doubleheader sweep. “He’s always in shape. He’s always ready when you call on him. I know a few guys in this league who could take some lessons from him.”

But the Pirates were unable to win the NL East title for a fourth straight season in a year when they were without Clemente, who died in a plane crash on New Year’s Eve 1972. Hernández finished the season batting .247 in 54 games but came to the plate only 78 times. He was a ninth-inning defensive replacement at shortstop in Pittsburgh’s final game of the year on Oct. 1 – which wound up being the final MLB game of Hernández’s career.

Alley retired following the 1973 season, and the Pirates decided that young Frank Taveras was ready for fulltime duty at shortstop. On Jan. 31, 1974, the Pirates traded Hernández to the Phillies in exchange for catcher Mike Ryan.

On April 4 – two days before Opening Day – the Phillies waived Hernández. He soon returned to Pittsburgh and was assigned to Triple-A Charleston, where he spent the whole season – hitting .199 over 115 games. He then played two years in the Mexican League and made other stops with teams around the Caribbean before his playing career ended.

After playing in some over-40 leagues, Hernández joined the coaching staff of the Duluth-Superior Dukes of the Northern League in 1998, teaming up with fellow Cuban Mike Cuellar on the staff. The Dukes also featured Ila Borders, who broke barriers as a pitcher.

Hernández later coached for independent league teams in Waterbury, Conn.; Paterson, N.J.; and St. Paul, Minn. Then in 2007, Hernández became the manager of the Charlotte County Redfish of the South Coast League.

“I loved the way (Danny Murtaugh) treated the players as a manager,” Hernández told the Port Charlotte (Fla.) Sun. “(And Royals manager) Joe Gordon, I loved the guy. He respected me.

“I like to play hard – stealing bases, hits and runs. When I was a player, I liked…bunts, squeeze plays. It’s what I like to do most.”

Hernández finished his nine-year playing career with a .208 batting average over 618 games, totaling 308 hits, 153 runs scored and 12 home runs. He also struck out 324 times to become the first non-pitcher in MLB history with at least 320 strikeouts, fewer than 320 hits and more than 600 games played.

But Hernández never let his struggles at the plate define him. Instead, Hernández simply enjoyed the life baseball afforded him.

“I’m not a good hitter,” Hernández told the Kansas City Star in 1969. “No power, you know. But I’m really trying.

“My fielding is my fielding. I don’t imitate anybody. I always try to field the Jackie Hernández way.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum