- Home

- Our Stories

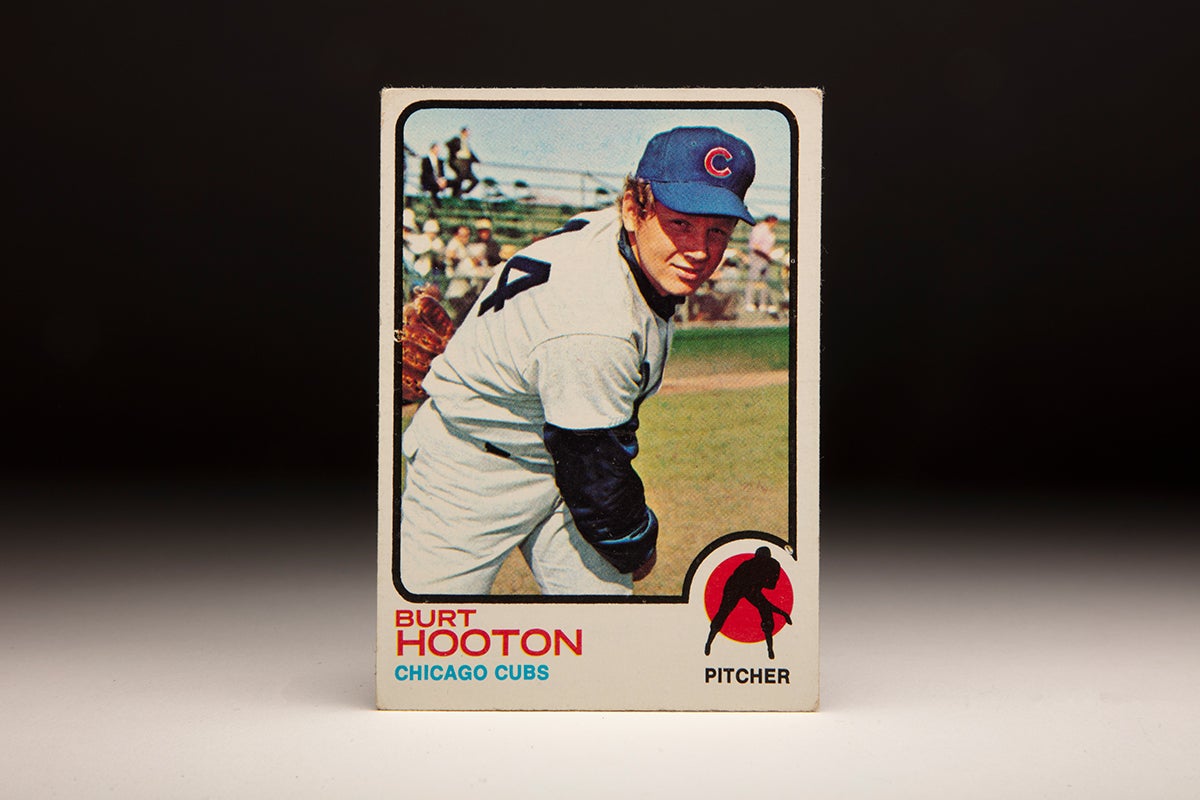

- #CardCorner: 1973 Topps Burt Hooton

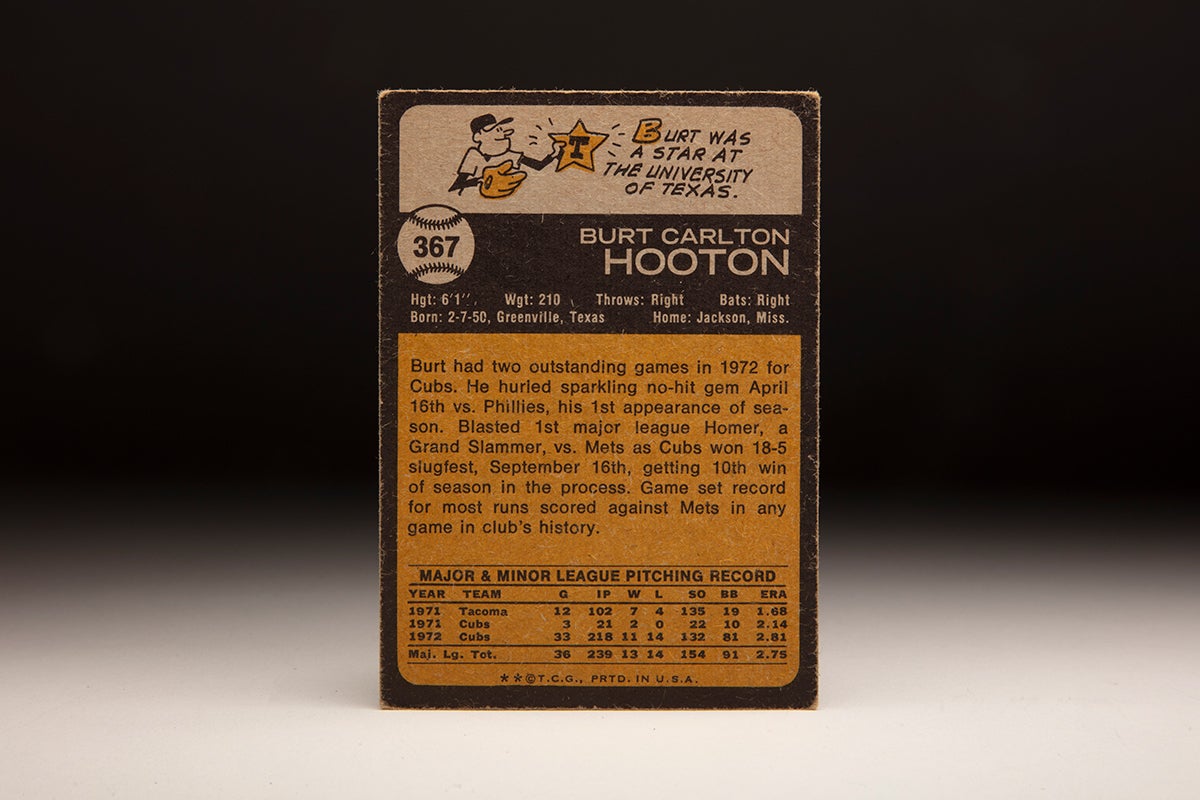

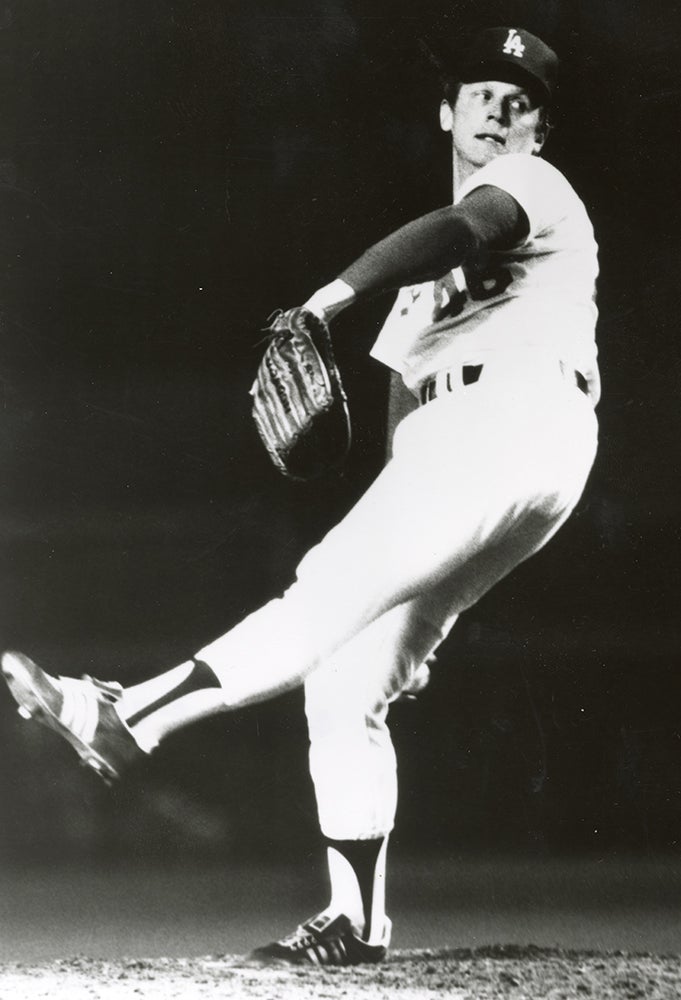

#CardCorner: 1973 Topps Burt Hooton

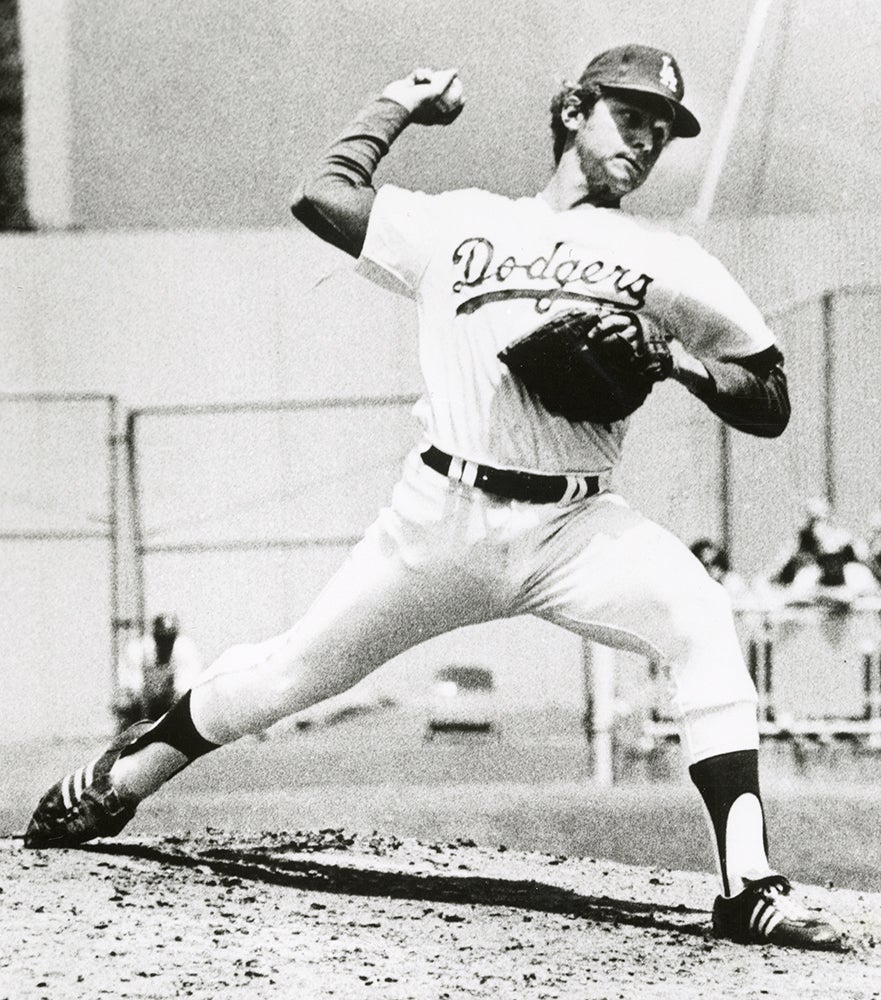

When Burt Hooton arrived in the big leagues, most baseball fans had never heard of a knuckle curve.

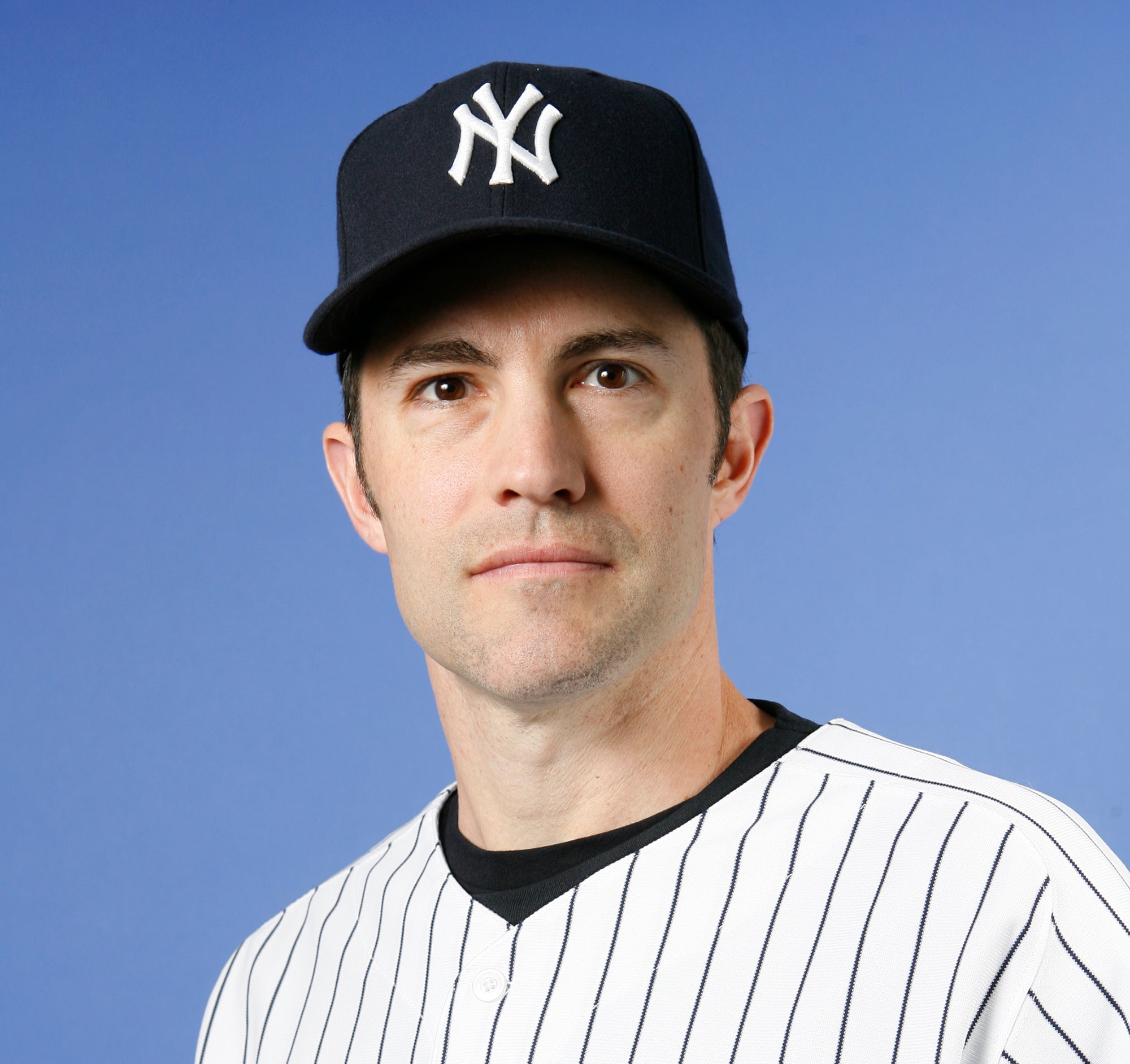

Today, the pitch is thrown by many big leaguers and was mastered by Hall of Famer Mike Mussina en route to Cooperstown. But few ever had more success with an unproven pitch than Hooton, who threw a no-hitter in just his fourth big league start.

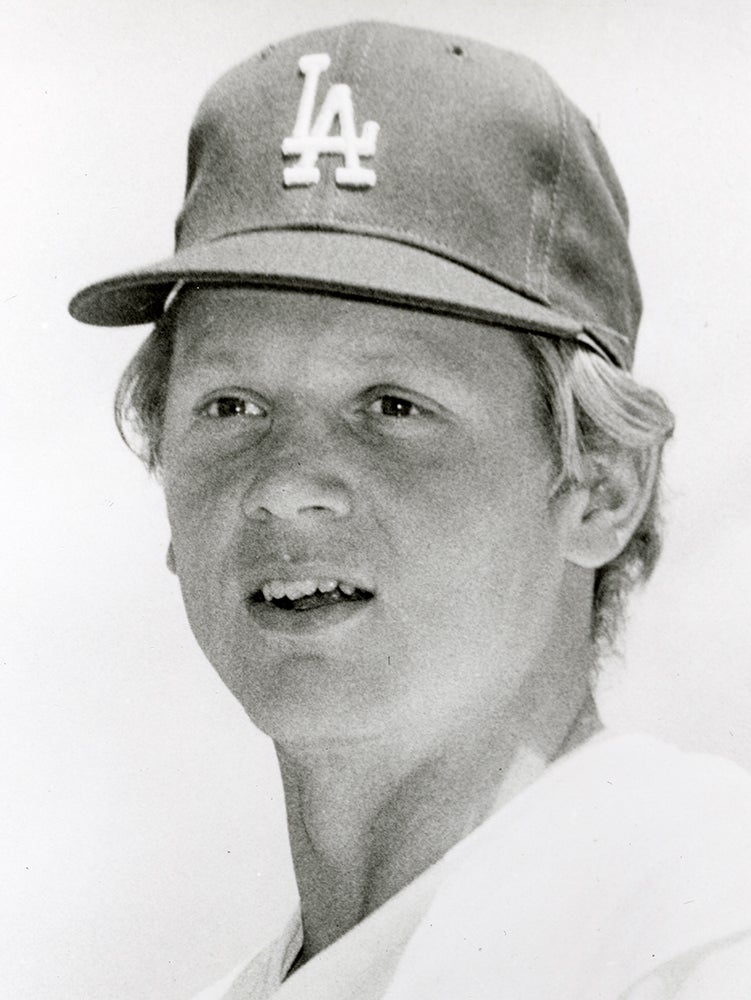

Burt Carlton Hooton was born Feb. 7, 1950, in Greenville, Texas, and grew up in Corpus Christi. He pitched three no-hitters as a high school junior in 1967 and led King High School to the Texas State Baseball Tournament while winning the Amarillo Chamber of Commerce Texas high school outstanding player award.

By that time, he was already using the knuckle curve.

“When I was 14, playing in the Pony League, I had seen (knuckleballer) Hoyt Wilhelm pitch on TV,” Hooton told the Associated Press in 1977. “I started experimenting putting my knuckles on the ball. Most knuckleball pitchers throw it off the tips of their fingers. I still throw it with the knuckles on the seams. It puts forward spin on the ball and makes it break down.”

After graduating high school in 1968, Hooton was selected by the Mets in the fifth round of the MLB Draft. But Hooton opted instead to enroll at the University of Texas. He had injured a leg playing basketball in his senior year – a mishap that proved a break for the Longhorns.

“If Burt hadn’t hurt his leg playing basketball his senior year, there’s no way we – or any other college – could possibly have recruited him,” Texas head coach Cliff Gustafson told the Austin American. “He would have undoubtedly had such an outstanding senior year in baseball that the pros would have met his price (reportedly $75,000).”

He was a freshman sensation in 1969, leading Texas to the College World Series with a 10-0 regular season record and earning a spot on the American Association of College Baseball Coaches All-America team.

In the first round of the College World Series in Omaha, Neb., Hooton pitched a four-hitter to lead the Longhorns past Arizona State 4-0. Texas eventually lost to New York University in the semifinals – and New York University fell to Arizona State, which came all the way back through the losers’ bracket, in the championship game. For his efforts, Hooton was named to the CWS All-Tournament Team.

“Hooton is the best college pitcher we’ve ever faced – or seen,” Arizona State head coach Bobby Winkles told the Austin American.

As a sophomore, Hooton again helped Texas advance to the CWS, where the Longhorns advanced to the semifinals once again. Heading into his junior season, Hooton pitched for Team USA at the World Amateur Baseball Championship and threw a no-hitter against Team Cuba after tossing a two-hitter against The Netherlands.

The Longhorns did not qualify for the College World Series in 1971 but Hooton was again named to the All-America team and was selected as the second overall pick in the Secondary Phase of the June 1971 MLB Draft – for players who were previously drafted but not signed – by the Cubs.

Hooton finished his career at Texas with a record of 35-3 and 1.14 ERA and signed with Chicago for a reported $50,000.

“I’m not sure I ever expect to see another (pitcher) any better (than Hooton) in college baseball,” Gustafson told the American. “I think the reason for that is obvious. If one does come along with that kind of ability, the pros are going to sign him right out of high school, no matter how much money it takes.”

The Cubs brought Hooton directly to the big leagues, and he made his first start on June 17, 1971, against the Cardinals – pitching 3.1 innings and allowing three hits (including a home run by future Hall of Famer Joe Torre), five walks and three runs. Hooton was then sent to Triple-A Tacoma, where he dominated over 12 starts – going 7-4 with a 1.68 ERA and 135 strikeouts in 102 innings. He tied a Pacific Coast League record with 19 strikeouts in one game against Eugene.

Recalled to Chicago in September, Hooton struck out 15 Mets batters in his first start back in a 3-2 win on Sept. 15. He followed that with a shutout of the Mets on Sept. 21, allowing just two hits and three walks.

“It’s an unusual pitch for a youngster to have,” Mets manager Gil Hodges told the AP. “And it’s a tough pitch to lay off.”

Hooton finished his first big league season with a 2-0 record and 2.11 ERA. Then in 1972, he picked up where he left off by throwing a no-hitter in his first start – just his fourth overall in the big leagues – in a 4-0 Cubs win on April 16 at Wrigley Field. He became the first NL rookie pitcher to author a no-hitter since the Giants’ Jeff Tesreau on Sept. 6, 1912.

After the no-hitter, the Associated Press reported that the Cubs tore up Hooton’s contract and gave him a new one with a $2,500 raise.

The National League finally began to catch up with Hooton after that, though he did toss three straight complete games in May and finished the season with an 11-14 record and 2.80 ERA over 218.1 innings.

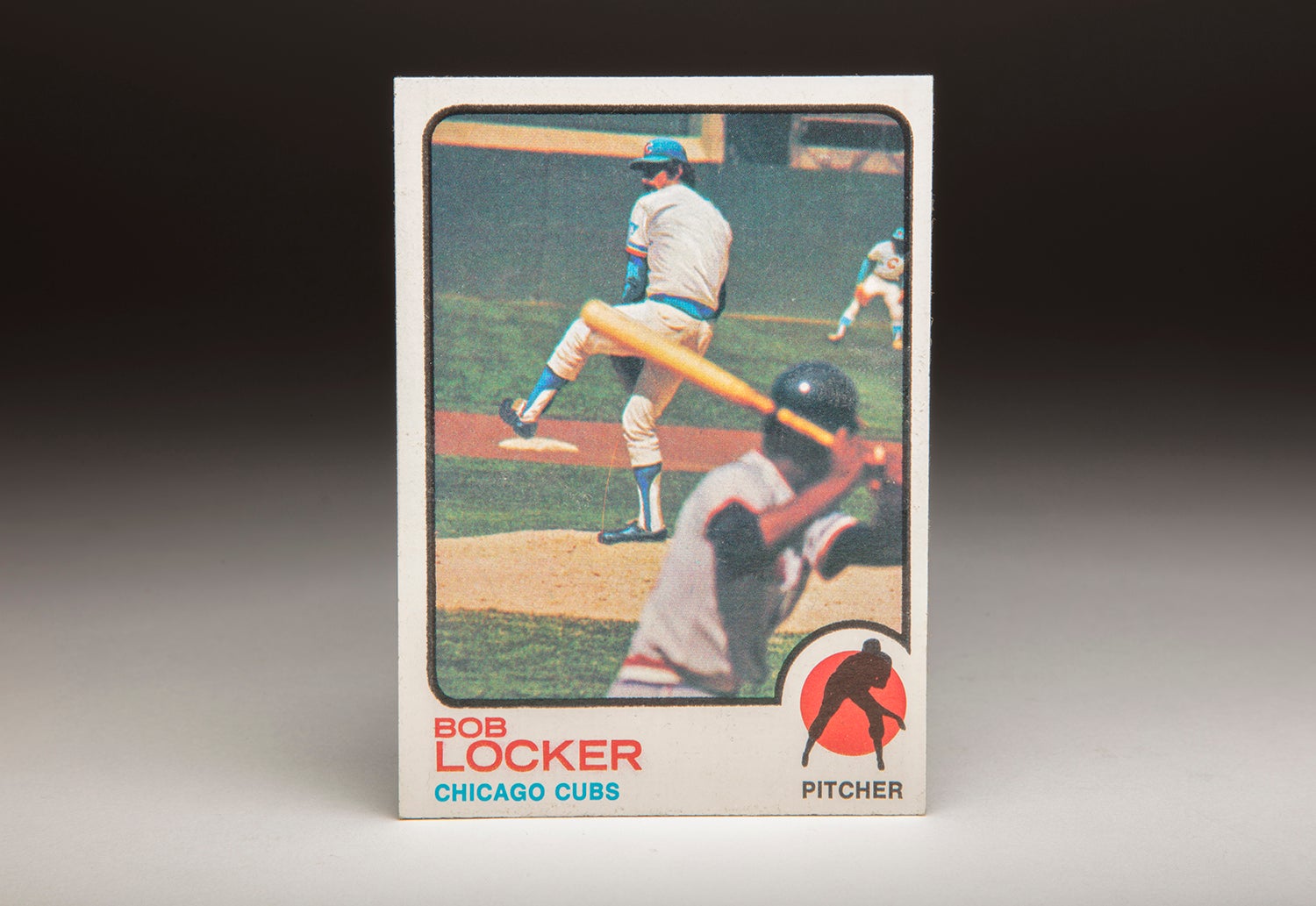

But in 1973, Hooton was not effective early in the season, save for a shutout against the Mets on April 19. He was demoted to the bullpen twice for short stretches and finished the season with a 14-17 record and 3.68 ERA.

Things got worse in 1974 as Hooton began the season 2-5, was moved to the bullpen in June and was working on a 4-11 mark in mid-September before three straight wins brought his final record to 7-11 with a 4.80 ERA.

“I’d like to burn the whole ballpark down and start the season over,” Hooton told the Chicago Tribune in July when his record was 3-10. “Now my confidence is going; I’d say it’s about gone. I (seem) to have lost my instinct for pitching.”

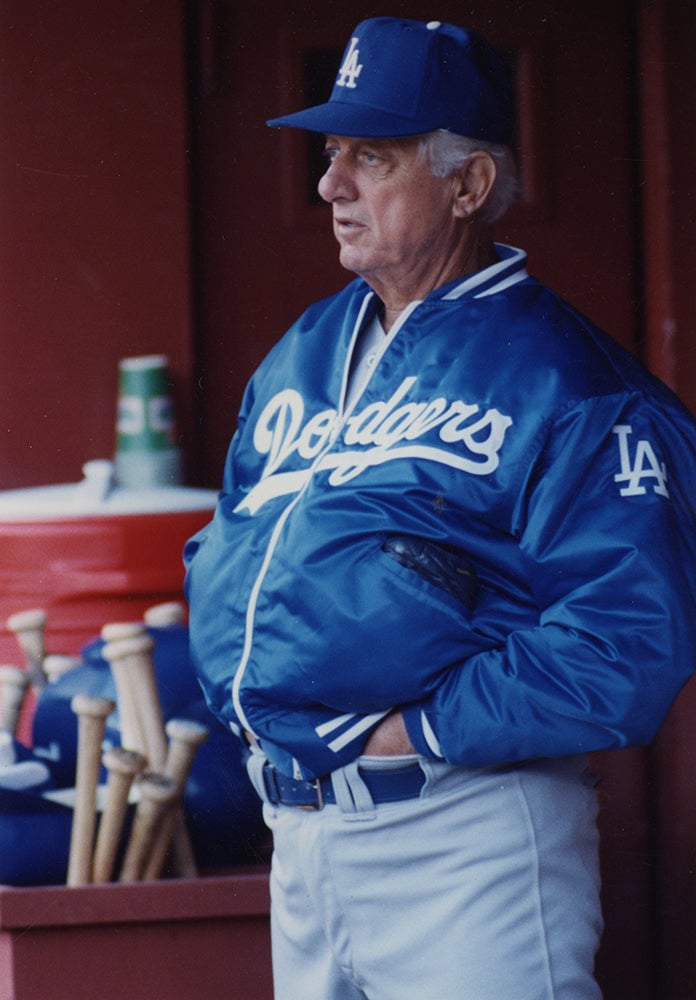

After the 1974 season, Hooton pitched in the Dominican Republic and worked with Dodgers coach Tommy Lasorda, who tagged him with the nickname – “Happy” – that would stay with Hooton throughout his career. Lasorda was with Hooton during a New Year’s Eve party, noticed Hooton playing solitaire and commented aloud about how “happy” Hooton appeared.

Hooton began the 1975 season 0-2 with an 8.18 ERA in three starts before the Dodgers – with Lasorda’s support – took a chance and acquired Hooton in a deal for young pitchers Eddie Solomon and Geoff Zahn on May 2, 1975. It was a trade that saved Hooton’s career.

“I honestly believe I would have been out of baseball now if the Cubs hadn’t traded me when they did,” Hooton told the Chicago Tribune in 1979. “If I had stayed in Chicago in 1975, I probably would have found myself in Triple-A ball and that would have finished me the way things were going.”

Hooton struggled at first with the Dodgers before a 20-minute session with a hypnotist helped him relax. Hooton won his last 12 decisions – breaking a team record held by Sandy Koufax – to go from 6-9 in mid-July to 18-9 at season’s end. In August and September, he totaled eight complete games while earning NL Pitcher of the Month honors in both months.

“All I know,” Hooton told the Los Angeles Times, “was that I was uptight and negative before (visiting the hypnotist) and I came out relaxed and positive.”

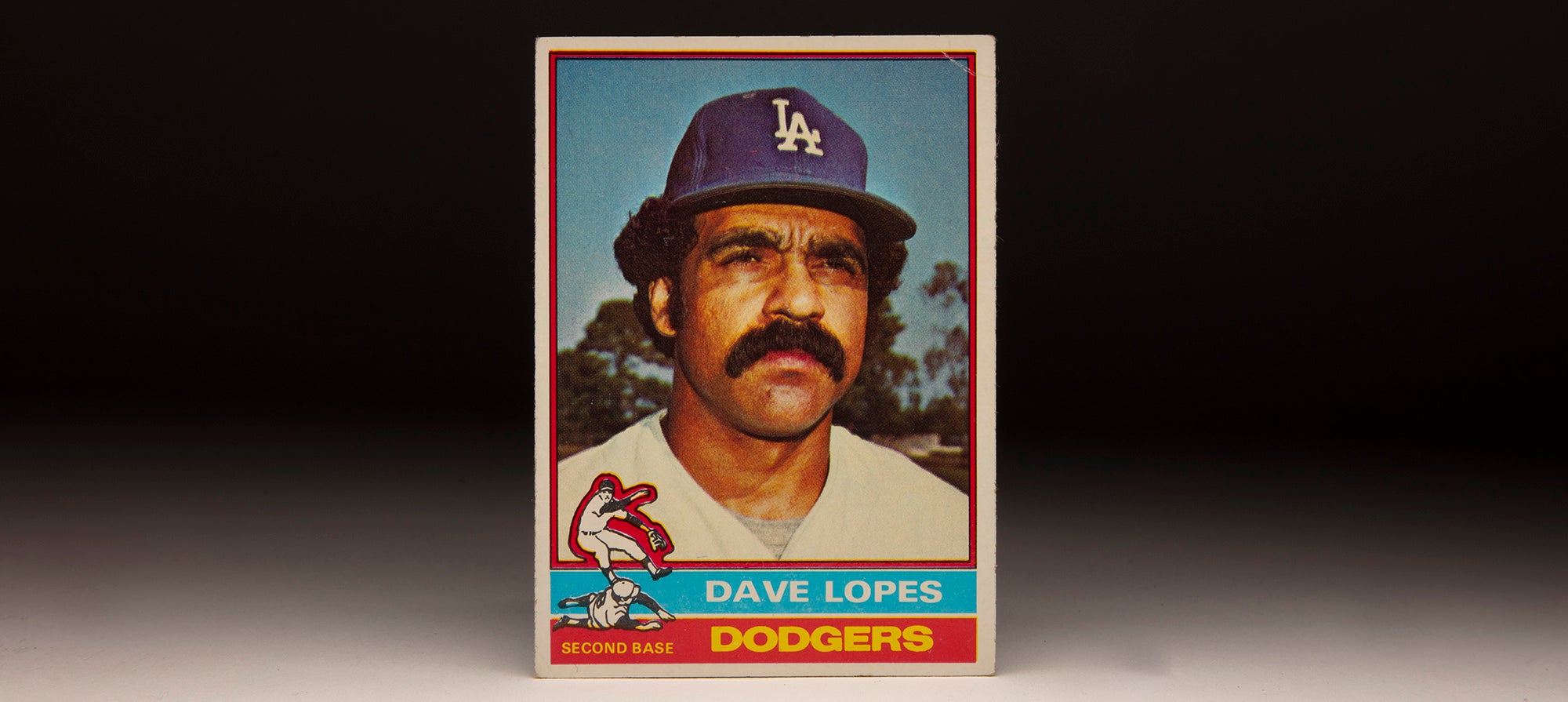

Hooton posted a hard-luck 11-15 record in 1976, working to a 3.26 ERA over 226.2 innings while suffering nine losses in games where the Dodgers scored two-or-fewer runs. Then in 1977, the Dodgers – with Lasorda in his first full year as manager – stormed to the NL pennant with a lineup that featured four players with at least 30 home runs in Dusty Baker, Ron Cey, Steve Garvey and Reggie Smith.

Hooton was 12-7 with a 2.62 ERA and topped all Los Angeles pitchers with a 5.4 Wins Above Replacement figure.

“It’s a hellacious pitch,” Dodgers catcher Steve Yeager told the AP about Hooton’s knuckle curve in 1977. “It will go in three different directions, depending on the positioning of his fingers on the ball and the way he releases it.”

Hooton allowed three runs over 1.2 innings in his first postseason start in Game 3 of the NLCS vs. the Phillies – a game the Dodgers came back to win 6-5. Then in Game 2 of the World Series against the Yankees, Hooton allowed five hits and one earned run while striking out eight in a complete game win at Yankee Stadium.

“My knuckle curve was my out pitch tonight,” Hooton told the AP after the 6-1 Dodgers victory. “I used it in all the tough situations, when the Yankees had men on base in the early innings.”

The victory tied the series at a game apiece.

“He had a nasty knuckle curve tonight,” Lasorda told the AP after Game 2, “and a few of those Yankees went after it like they’d never seen one before – and, of course, they hadn’t.”

But the Yankees adjusted. The Dodgers entered Game 6 trailing three-games-to-2, and his teammates staked Hooton to a 2-0 lead in the top of the first. But in the bottom of the second, Reggie Jackson walked to lead off the frame and immediately scored when Chris Chambliss followed with a homer to tie the score. Reggie Smith put the Dodgers ahead 3-2 with a third-inning home run, but Jackson hit a two-run home run in the fourth to give New York a 4-3 lead. It would be the first of three homers Jackson would hit on the night and chased Hooton from the game.

The Yankees went on to win 8-4 to capture the title.

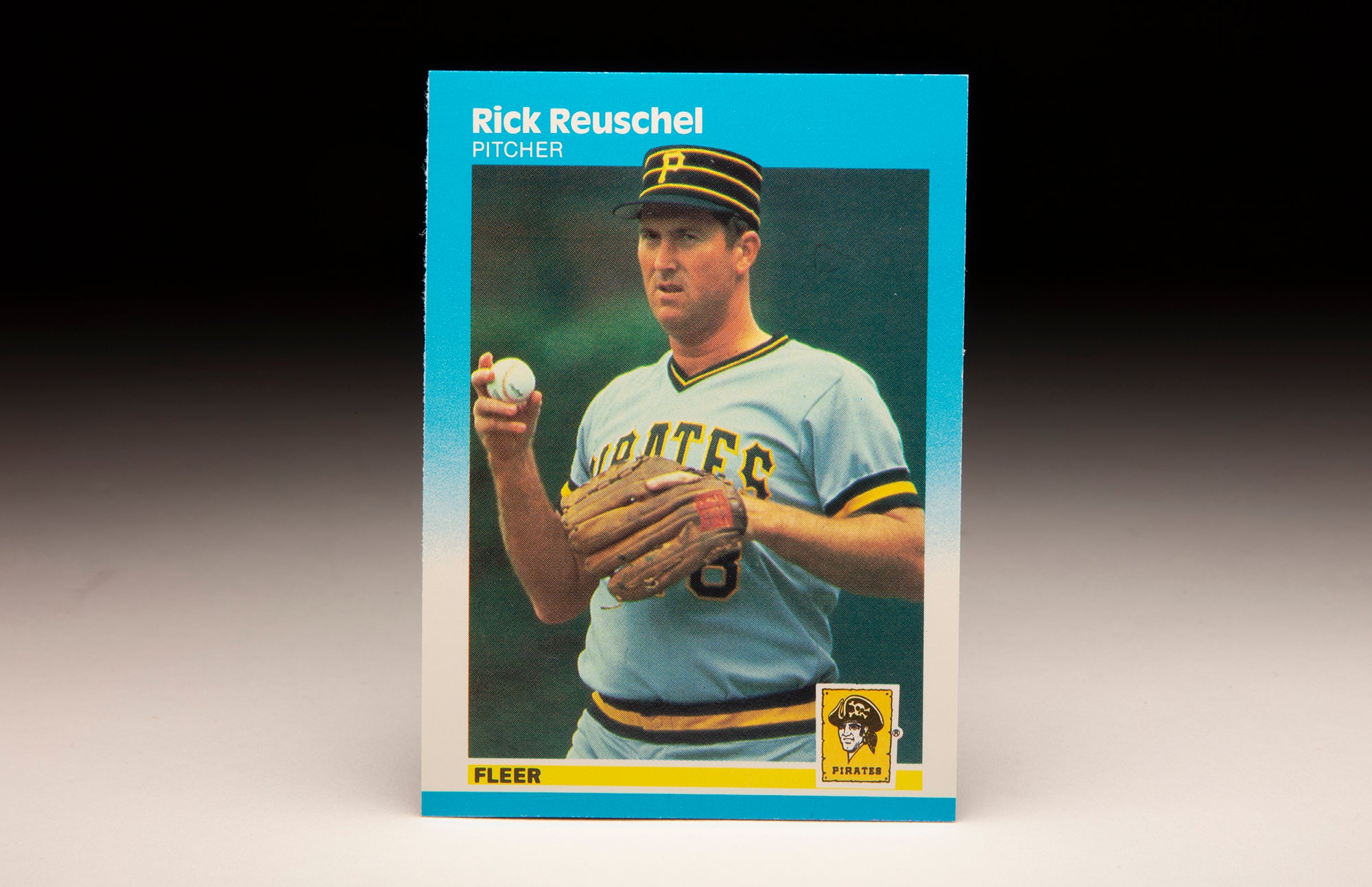

In 1978, the Dodgers and Yankees met again in the World Series after Hooton had what may have been his best big league season. He won a career-high 19 games against only 10 losses, posting a 2.71 ERA over 236 innings. He would finish second in the NL Cy Young Award voting and 15th in the NL Most Valuable Player race – the only time in his career that Hooton was named on either ballot.

Hooton once again struggled in his NLCS start vs. the Phillies, allowing 10 hits and four runs over 4.2 innings in a 9-5 Game 1 win by the Dodgers. Hooton again started Game 2 of the World Series against the Yankees and again posted a victory, this time allowing three runs over six innings in a 4-3 Dodgers victory that put L.A. ahead two-games-to-nothing. But the Yankees stormed back with four straight wins, including a 12-2 win in Game 5 where Hooton allowed four runs (three earned) in 2.1 frames.

In the spring of 1979, Hooton agreed to a five-year contract extension with the Dodgers after weeks of negotiations. He earned his first Opening Day start and was 11-10 with a 2.93 ERA heading into September when a shoulder injury sidelined him for the rest of the year after he pitched just one-third of an inning Sept. 4. He returned to form in 1980, however, going 14-8 with a 3.66 ERA in 206.2 innings – the eighth time in nine seasons he would reach the 200-inning mark.

Hooton started on Opening Day in 1980 and started the regular season finale – a game against the Astros that the Dodgers had to win to force a one-game playoff for the NL West title. Hooton was lifted in the top of the second inning after Houston scored two runs, but the Dodgers rallied to win the game 4-3 behind excellent bullpen work – including two scoreless innings by young Fernando Valenzuela.

But the Astros beat the Dodgers 7-1 the next day in the playoff to win the NL West and keep Los Angeles out of the postseason for the second straight season.

In 1981, however, the Dodgers finally claimed their elusive World Series title behind a magical season from Valenzuela, who won the NL Rookie of the Year and Cy Young awards. It was Hooton, however, who led all Los Angeles starters with a 2.28 ERA while going 11-6 and earning the only All-Star Game selection of his career.

Hooton started Game 3 of the NLDS vs. Houston, and with Los Angeles down 2-games-to-nothing in that best-of-5 series Hooton allowed just three hits and one run over seven innings as the Dodgers won 6-1. Los Angeles won the next two games to advance to the NLCS vs. Montreal, and Hooton drew the Game 1 start, allowing just six hits over 7.1 shutout innings in a 5-1 Dodgers win. Hooton returned in Game 4 with another 7.1 innings, permitting just one unearned run in a 7-1 victory.

After the Dodgers won Game 5 to clinch the series, Hooton was named the NLCS Most Valuable Player.

“We have a bunch of guys who aren’t willing to give up,” Hooton told the Flint (Mich.) Journal after Game 5 of the NLCS. “They say it’s not over until it’s over and, boy, we’ve proved that.”

Hooton started Game 2 of the World Series and was tagged with a hard-luck loss after giving up just one unearned run over six innings in a 3-0 loss. That defeat dropped the Dodgers into a two-games-to-nothing hole but Los Angeles roared back with four straight wins – with Hooton picking up the win in the deciding Game 6 with 5.1 innings of two-run ball.

It would be the apex of Hooton’s big league career.

In 1982, Hooton got off to a slow start and was 1-4 with a 5.37 ERA in mid-June when a knee injury sidelined him for two months. He pitched better upon his return and brought the Dodgers to within one game of the division-leading Braves by holding Atlanta to three runs over 5.1 innings in a 10-3 Los Angeles win on Sept. 30 in the final game of the season between the two squads. But the teams matched wins and losses over the final three days of the season to give the Braves the division title.

Hooton, who finished the year with a 4-7 record and 4.03 ERA in 21 starts, was not impressed by his late-season work.

“How can anybody call me a money pitcher after what I did in ’77,” Hooton told the Atlanta Constitution before the Sept. 30 game against the Braves, referring to his first postseason start in Game 3 of the NLCS vs. the Phillies in 1977. “I blew up. I lost it. I hadn’t done anything in those situations until last year. I’m just one of the pitchers who can keep us in the game.”

But despite his own misgivings about his talent, Hooton was still well respected by Lasorda and the Dodgers’ front office. He started the team’s third game of the 1983 season and was 8-2 with a 3.34 ERA in July when a five-game losing streak cost him his rotation spot in September. He finished the year 9-8 with a 4.22 ERA but did not pitch in the team’s NLCS loss against the Phillies.

Entering the final year of his contract in 1984, Hooton was unable to crack a Dodgers starting rotation that featured Valenzuela, Rick Honeycutt, Alejandro Peña, Jerry Reuss and a young Orel Hershiser. Hooton spent the season as a middle reliever, going 3-6 with four saves and a 3.44 ERA in 54 games.

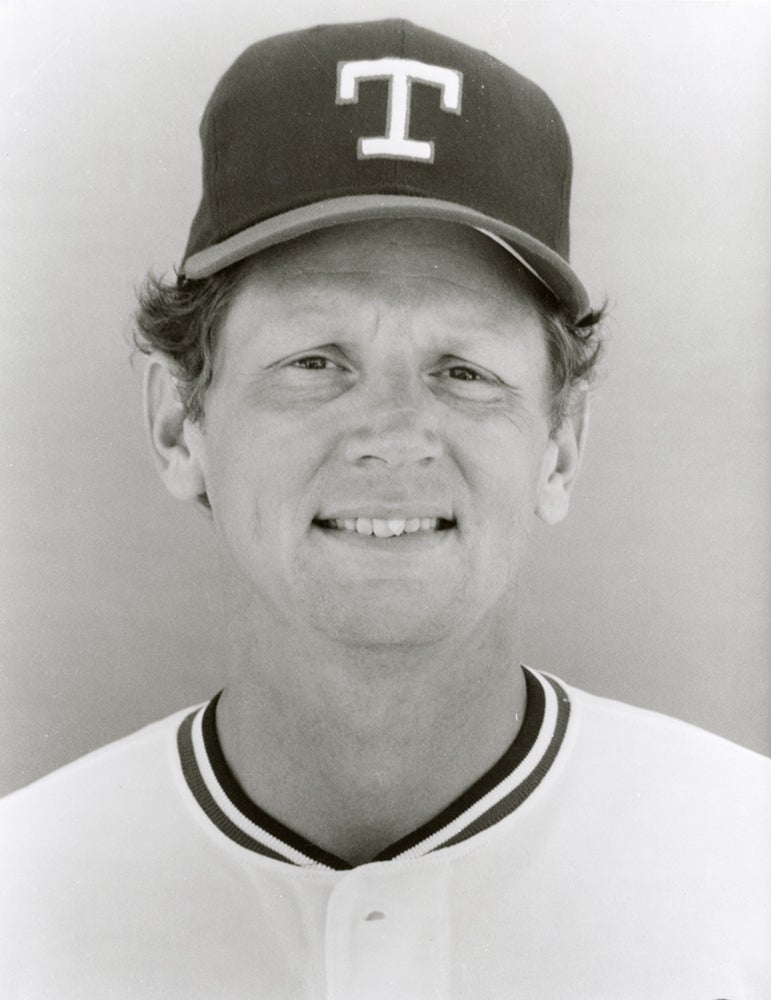

On Dec. 20, 1984, Hooton signed a three-year deal with the Rangers, who planned to deploy Hooton in the starting rotation while moving Hooton’s former Dodgers teammate Dave Stewart to the bullpen.

“There’s no guarantee that he’ll start,” Rangers general manager Tom Grieve told reporters. “But there’s an understanding that he will be a starter.”

But Hooton worked out of the bullpen until mid-May. When he joined the rotation, he was largely ineffective and finished the year with a 5-8 record and 5.23 ERA over 124 innings.

On March 27, 1986, the Rangers released Hooton.

“Nothing lasts forever,” Hooton told the South Florida Sun Sentinel after being released. “I’ve tried to turn things around the last few years, but it hasn’t been there. Mentally I had it, physically I didn’t. This spring, I’ve been there physically but it’s been tough mentally.”

Hooton would not pitch in the big leagues again.

Hooton soon turned to coaching and worked his way through the Dodgers’ farm system before returning to the University of Texas as the school’s pitching coach for three years. He then joined the Astros organization and assumed the role as the team’s big league pitching coach midway through the 2000 season, holding that job until midway through the 2004 campaign. He later coached in the Padres’ system.

Hooton compiled a 151-136 record over 15 big league seasons, posting a 3.38 ERA while striking out 1,491 batters over 2,652 innings. Though he never again dominated hitters as he did when he first broke into the majors, Hooton became a workhorse starter whose knuckle curve baffled batters throughout his career.

“The difference between myself and those who aren’t (in the big leagues) is talent,” Hooton told the Daily Chronicle of DeKalb, Ill., in 1973. “When a player makes it to the majors, he’s already been given 99 percent God-given talent. The other one percent is acquired through work.

“Some players reach their peak and there’s no potential for improvement. I think I’m still going to get better.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum