- Home

- Our Stories

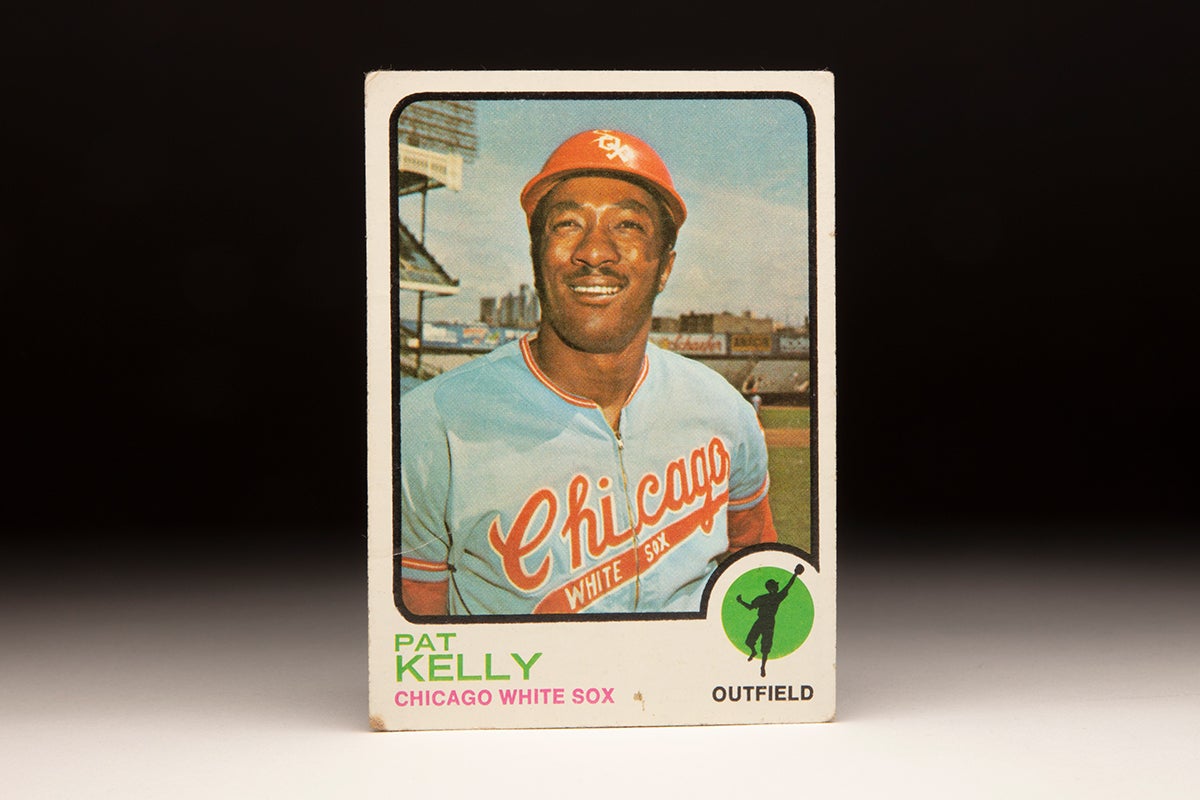

- #CardCorner: 1973 Topps Pat Kelly

#CardCorner: 1973 Topps Pat Kelly

He was the younger brother of a Pro Football Hall of Famer, but Pat Kelly made a name for himself on the diamond.

After 15 seasons in the big leagues, Kelly would have few regrets about his athletic journey.

Born July 30, 1944, in Philadelphia, Harold Patrick Kelly was the youngest of seven children. One of his older brothers, Leroy Kelly, played quarterback at Simon Gratz High School in Philadelphia before enrolling at Morgan State University in Baltimore, where he switched to running back. The Cleveland Browns selected Kelly in the eighth round of the 1964 NFL Draft, and he served as a topnotch punt and kickoff returner for two seasons while backing up the legendary Jim Brown.

When Brown unexpectedly retired prior to the 1966 season, Kelly took over at running back – rushing for 1,141 yards and scoring 16 touchdowns.

“Leroy really didn’t have a favorite sport but since Morgan State didn’t have a baseball team, he stuck to football,” Pat Kelly told United Press International in 1969. “Leroy always tells me he could play baseball and I like to tell him that I could carry the ball.”

Leroy Kelly played 10 seasons in the NFL, helping the Browns win the 1964 NFL Championship and leading the league in rushing, total yards from scrimmage and touchdowns in 1967 and 1968. He was elected to the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1994.

Pat, meanwhile, followed in Leroy’s footsteps at Simon Gratz High School, starring in football, basketball and baseball while winning the Med Cledeen Award as the outstanding high school athlete in Philadelphia during his senior year.

Unlike his brother, however, Pat Kelly was determined to play baseball.

“Ever since I can remember, I always wanted to be a baseball player,” Kelly told UPI. “So I decided to sign right after high school and I’ve been going to college (at Morgan State) in the offseason.”

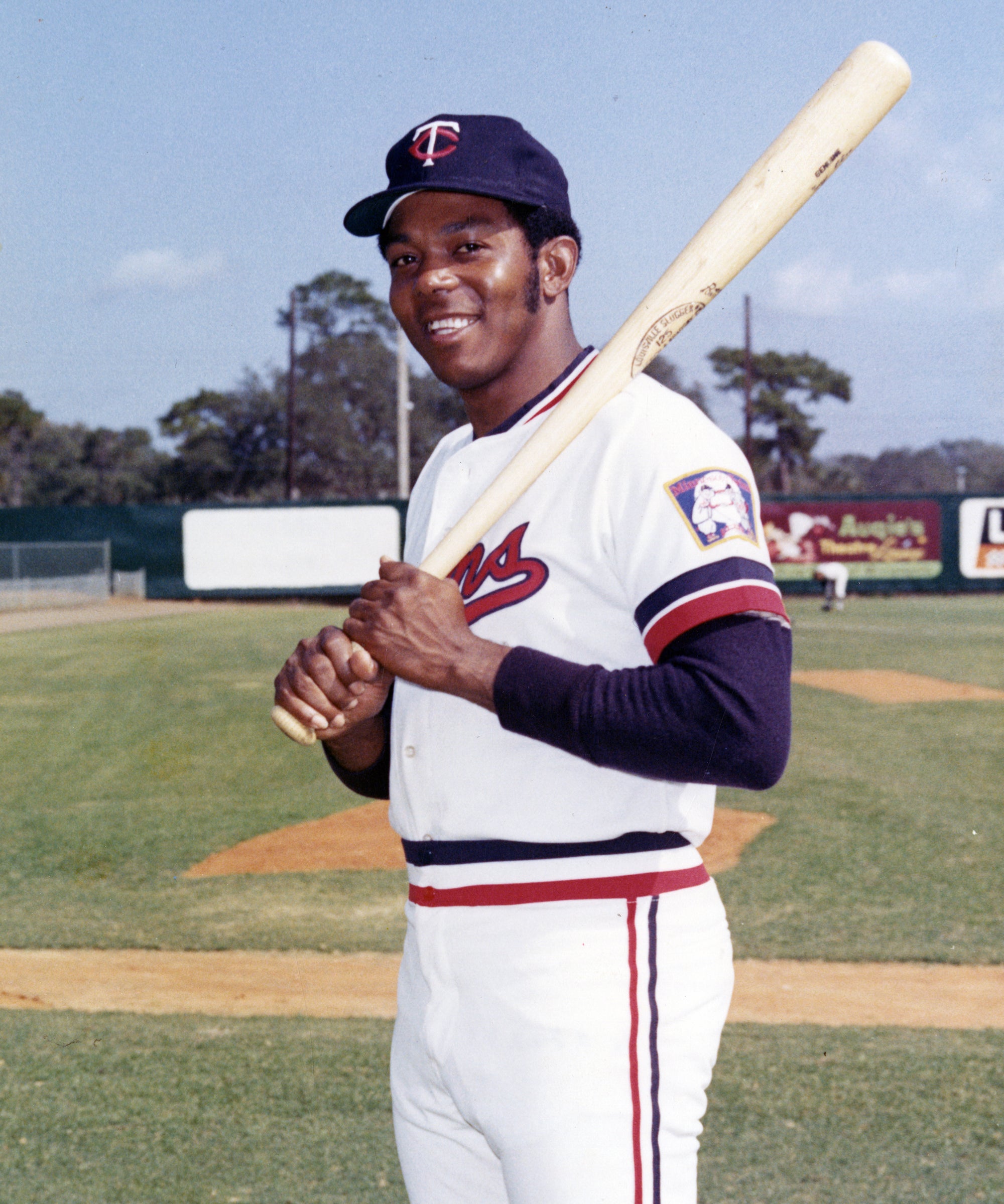

Kelly signed with the Minnesota Twins on Sept. 11, 1962, and began his pro career with the Class A Erie Sailors of the New York-Penn League. He hit .283 with 50 runs scored in 69 games before earning a promotion to Orlando of the Class A Florida State League, where he hit .242 in 49 games. For the season, Kelly posted a .381 on-base percentage in 118 games.

In 1964, Kelly was sent to Wisconsin Rapids of the Class A Midwest League, where he batted .357 (finishing third in the league batting race) with 16 homers, 70 RBI and 72 walks (good for a .458 on-base percentage) in 104 games. He also played a handful of games with Wilson of the Class A Carolina League before being selected to the Twins’ team in the Florida Winter Instructional League.

In 1965, Kelly spent the entire year with the Wilson Tobs, batting .283 with 27 steals, 119 walks and 101 runs scored in 144 games. Promoted to Double-A Charlotte in 1966, he was named a Southern League all-star while hitting .321 with 78 walks and 52 stolen bases in 113 games.

Kelly played most of the 1967 season with Triple-A Denver before earning a late-season promotion to the big leagues. The Twins were involved in a four-way race for the American League pennant with Boston, Chicago and Detroit – and Kelly saw action in eight games, all as a pinch-hitter or pinch-runner.

After the season, he returned to the Florida Winter Instructional League for the third time in four seasons, leading the loop in batting average for much of the campaign before finishing with a .292 mark (and .434 on-base percentage) in 40 games. But with a veteran outfield of Bob Allison, Ted Uhlaender and Tony Oliva in Minnesota, the Twins had no roster spot for Kelly.

He returned to Denver in 1968, batting .306 with 38 steals in 108 games before appearing in 12 games with the Twins in December. Kelly then got the break he was waiting for when the Royals selected him with the 34th pick in the Expansion Draft as MLB stocked new American League teams in Kansas City and Seattle.

“The great thing about expansion is it gives so many players who could get lost in the shuffle in the minors a chance to prove what they can do,” Kelly told UPI. “I was called up by the Twins at the end of 1967 but got only one at-bat and I was in just 12 games at the end of the 1968 season with them. That’s why I was so happy the Royals drafted me. The Twins outfield was pretty much set with players like (Tony) Oliva and (Ted) Uhlaender but I really got a chance with the Royals.”

Kelly took full advantage of his opportunity, earning a spot on the Opening Day roster and quickly moving into the starting lineup. By June, he had pushed his batting average close to the .300 mark and finished the season hitting .264 with 61 runs scored and 40 steals in 112 games.

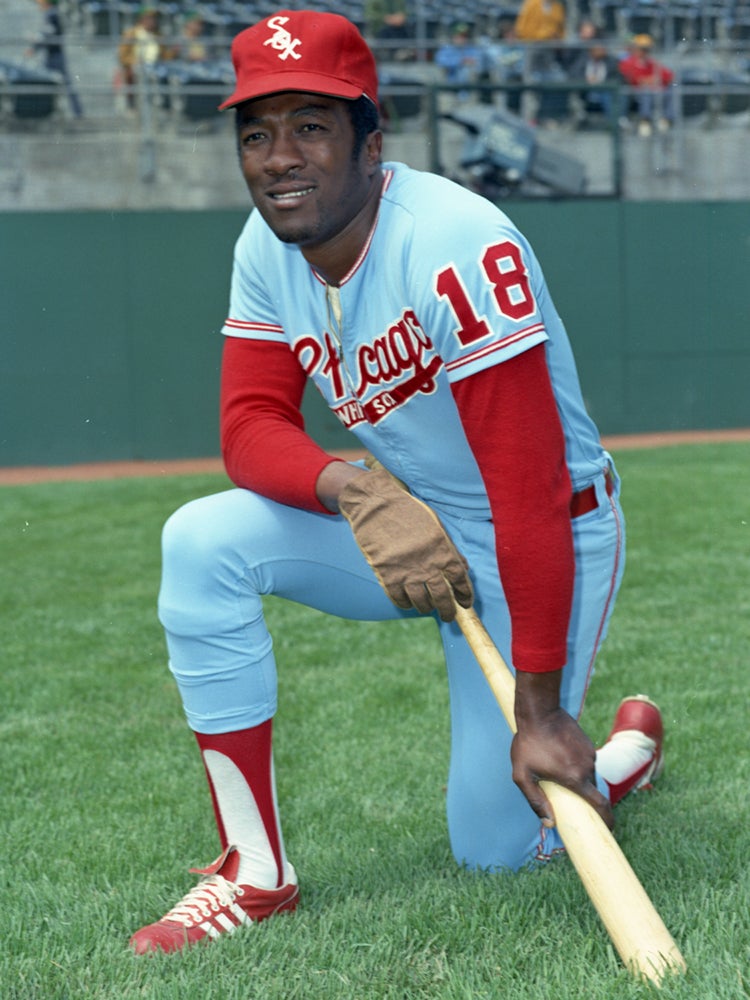

The lefty-swinging Kelly was the Royals’ Opening Day right fielder in 1970 and stayed in that position all season, batting .235 (but with a .348 on-base percentage) with 77 walks and 34 stolen bases while playing mostly against right-handed starters. Then, on Oct. 13, 1970, Kelly was traded to the White Sox with Don O’Riley in exchange for Gail Hopkins and John Matias.

The White Sox lost 106 games in 1970 but Kelly was unable to crack the Opening Day roster and instead was sent to Triple-A Tucson. He torched Pacific Coast League pitching for three months, hitting .355 with 71 runs scored in 75 games before being recalled to Chicago in July.

A change in batting philosophy changed the course of Kelly’s career.

“I sat down one day to figure myself out,” Kelly told the Wichita Eagle in 1973. “I decided the fly ball wasn’t doing me any good and so I moved up on the bat. This spring I am not having to hit the pitcher’s pitch but the one I want.”

He was the White Sox’s starting right fielder for most of the rest of the season, batting .291 with a .394 on-base percentage and 14 steals in 67 games.

Kelly would not play in the minor leagues again.

In 1972, Kelly reunited with longtime friend Dick Allen when Allen joined the White Sox following a trade from the Dodgers. Allen reported to Spring Training in Sarasota, Fla., on March 14 and quickly left the same day in a salary dispute – but not before chatting with Kelly.

“He looked great,” Kelly told the Associated Press about Allen, “and said he had a good winter.”

Allen soon returned to the White Sox and kickstarted an MVP season that saw him lead the AL in home runs (37), RBI (113) and walks (99). Kelly was the beneficiary of much of that hitting, scoring 16 runs on Allen RBI – the top figure for players driven in by Allen (other than himself) for the season.

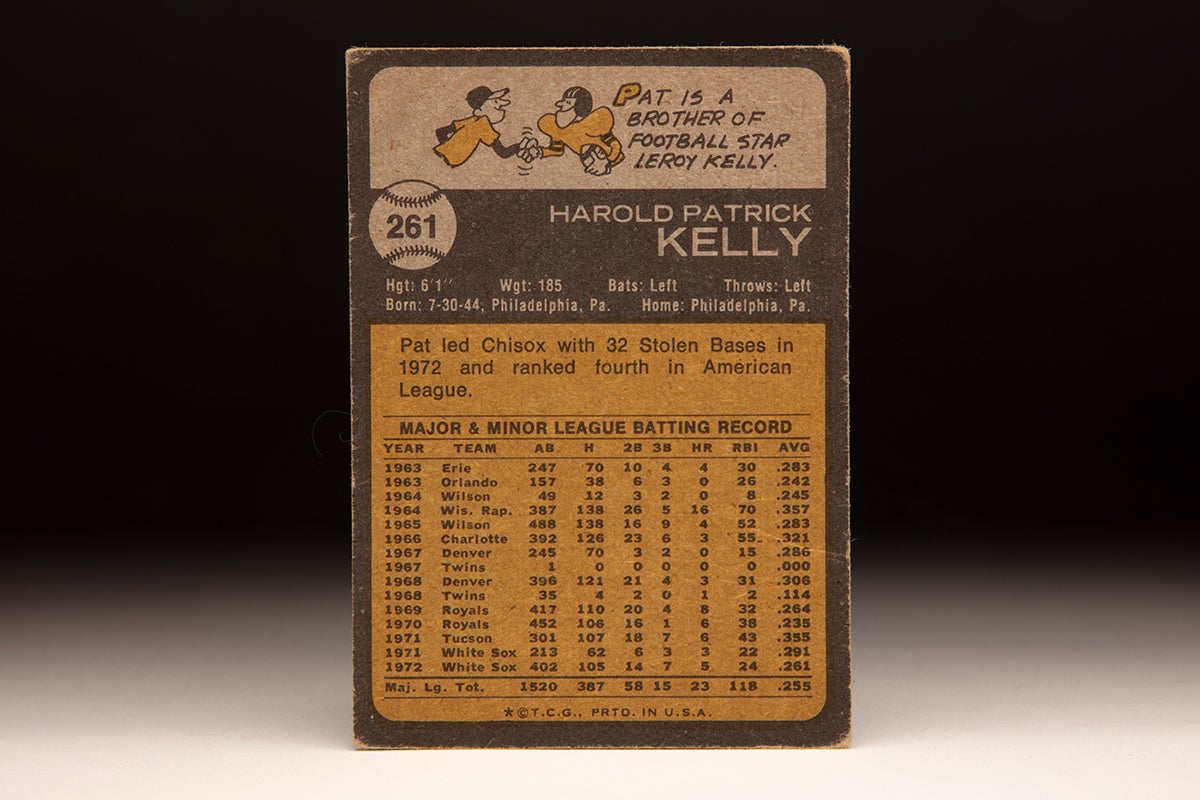

On the year, Kelly hit .261 with 55 walks, 32 steals and 57 runs scored in 119 games as the White Sox won 87 contests and became a trendy pick to advance to the postseason in the coming seasons. In the spring of 1973, Joe Garagiola said on NBC’s Today Show that he expected the White Sox to play in the World Series that year. But Allen missed much of the season with a broken leg, sabotaging Chicago’s dreams of a championship.

Kelly, however appeared in a career-best 144 games while batting .280 with 65 walks and 77 runs scored. A blistering start saw Kelly hitting .400 as late as May 17, and he was named to what would be his only All-Star Game, popping out to shortstop against Don Sutton in the fifth inning while pinch-hitting for Bill Singer.

In 1974, Kelly returned to a platoon role and batted .281 with 18 steals and 60 runs scored in 122 games. But the White Sox finished a disappointing 80-80 in what would be Allen’s final season with the team. Kelly also underwent shoulder surgery that year in an attempt to improve his outfield arm, which had always been considered weak.

In 1975, Chicago fell to 75-86 as Kelly hit .274 with 73 runs scored and 18 steals. He also posted a .353 on-base percentage – the fourth year in a row where Kelly played at least 119 games with an OBP of .350 or better.

But at that point, Kelly found himself at the nadir of his personal life. He said substance abuse robbed him of much of his identity.

“The Pat Kelly I had known for 30 years just stopped existing,” Kelly told the Baltimore Evening Sun in 1986.

Looking for a new start, Kelly – whose family raised him in the Baptist faith – enrolled in a Bible study class and soon devoted himself to Christianity.

“I had some good in me,” Kelly told the Chicago Tribune of his days before his Christian rebirth. “But I had a lot of bad – the street, the parties, the night life. But I went through some pretty heavy emotional changes.”

But while his personal life stabilized, his career on the diamond frustrated him as he appeared in only 107 games in 1976, batting .254 with a .349 OBP but coming to the plate just 366 times – his fewest plate appearances in the big leagues since the 1971 season.

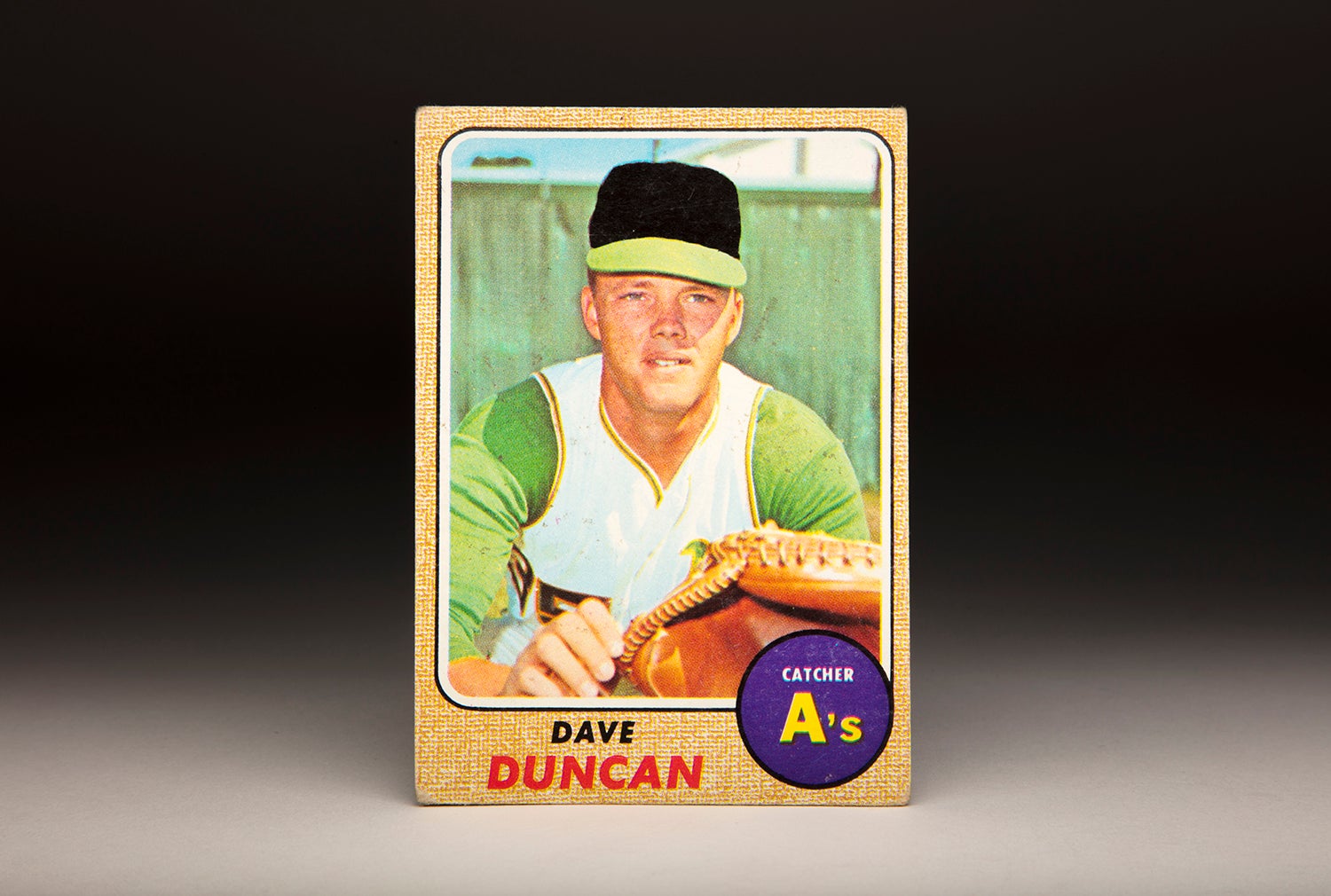

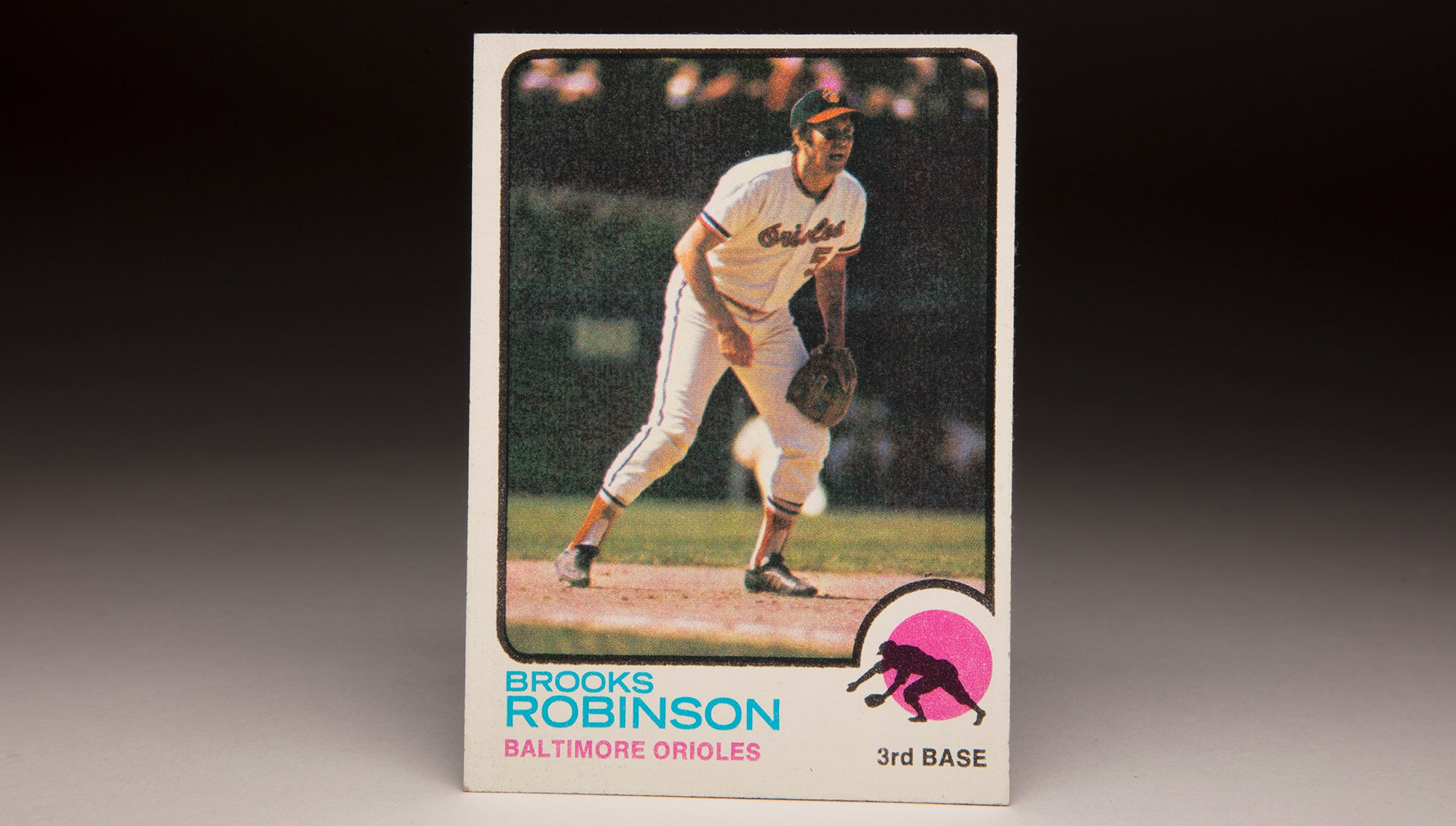

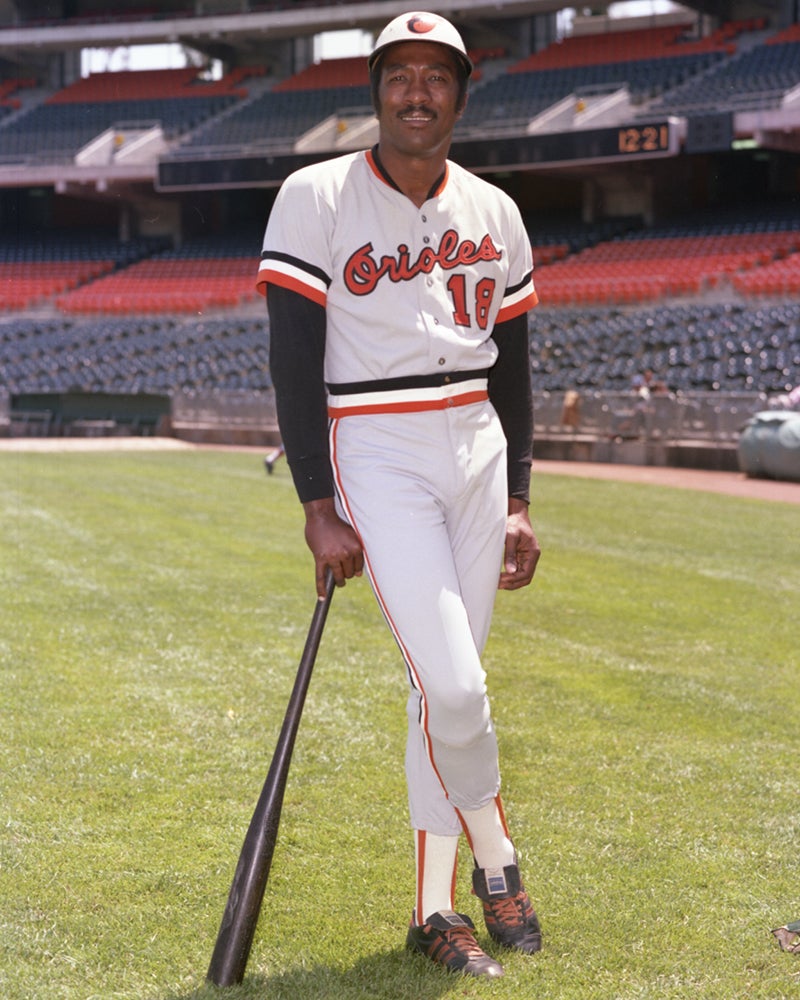

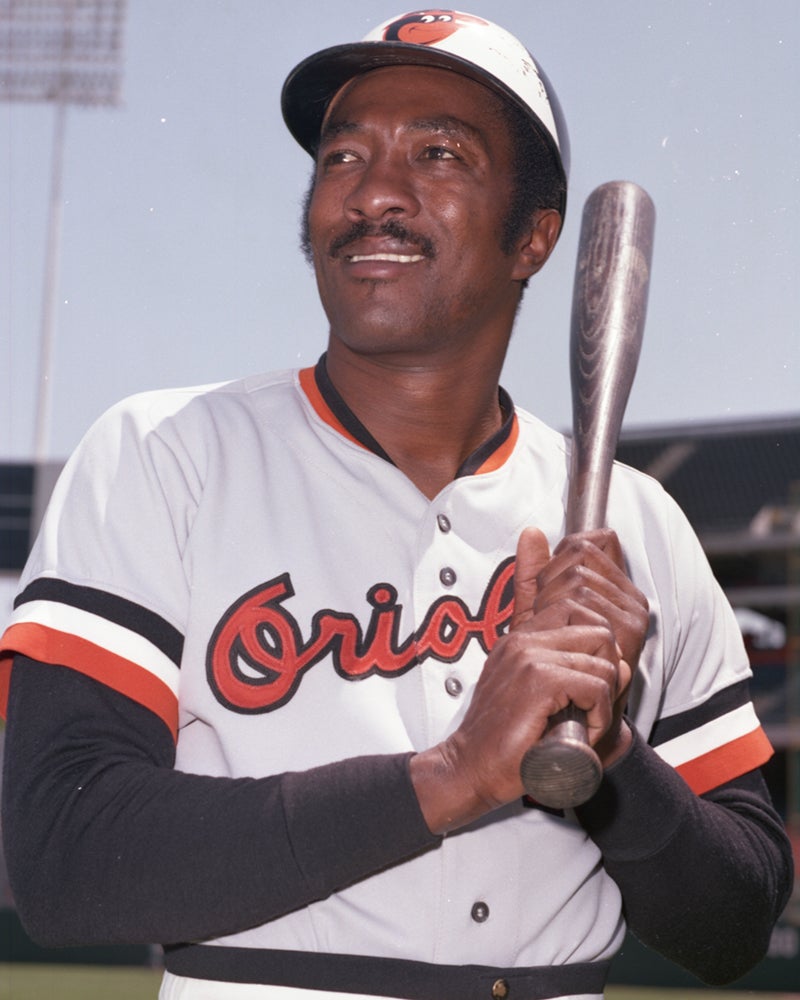

The White Sox went 64-97 under new manager Paul Richards, and on Nov. 18, 1976, Kelly was traded to the Orioles in a one-for-one deal for catcher Dave Duncan.

“We had talked on and off to the White Sox about Kelly,” Orioles general manager Hank Peters told the Baltimore Sun. “Kelly gives us a good left-handed designated hitter and some added depth in the outfield.”

For the next four seasons, Kelly perfectly filled Peters’ prescription. Kelly hit 10 home runs, drove in 49 runs and stole 25 bases in 1977 – while putting together a 19-game hitting streak in May – and followed up with 11 homers, 40 RBI and 10 steals in 1978, earning a two-year contract extension that covered the 1979 and 1980 seasons.

“I couldn’t have been happier,” Kelly told the Evening Sun in 1977 about the trade, which he learned about when he was playing winter ball in Venezuela. “(The Orioles are) a good team and a good organization. Whatever they want me to do, I’ll do.”

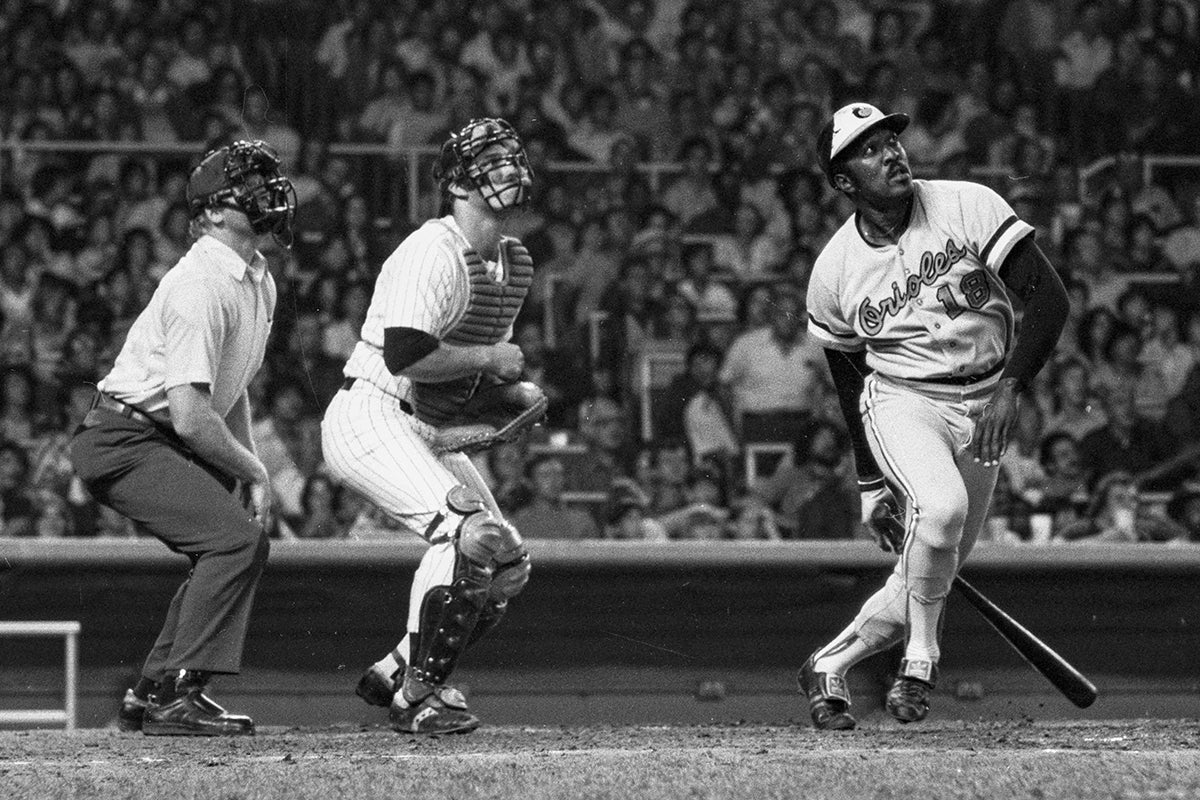

His playing time diminished in 1979 on a deep Orioles team that steamrolled to the American League pennant, but Kelly still played an important role by hitting .288 with nine homers in 68 games. He appeared in his first career postseason game in Game 1 of the ALCS vs. the Angels, going 1-for-3 with a walk and a run scored as the Orioles’ left fielder.

He was Baltimore’s DH in Game 2 and put the Orioles in front 2-1 with an RBI single in the bottom of the first inning, later scoring to give the O’s a 4-1 advantage. Baltimore won the first two games and Kelly sat out Game 3 as the Angels started lefty Frank Tanana. But Kelly returned in Game 4 and went 2-for-4 with three RBI, homering against John Montague in the seventh inning – a three-run shot that gave Baltimore an 8-0 lead and effectively salted away the series.

But after batting .364 with three runs scored and four RBI in the ALCS, Kelly did not start a game in the World Series against the Pirates. With no designated hitter rule in play for the Fall Classic that year, Kelly was limited to five pinch-hitting appearances. He went 1-for-4 with a walk and flew out to Pirates center fielder Omar Moreno to end Game 7.

“I have an empty feeling,” Orioles manager Earl Weaver told United Press International after the Pirates’ 4-1 victory. “We won 108 games all this year. But we fell one short.”

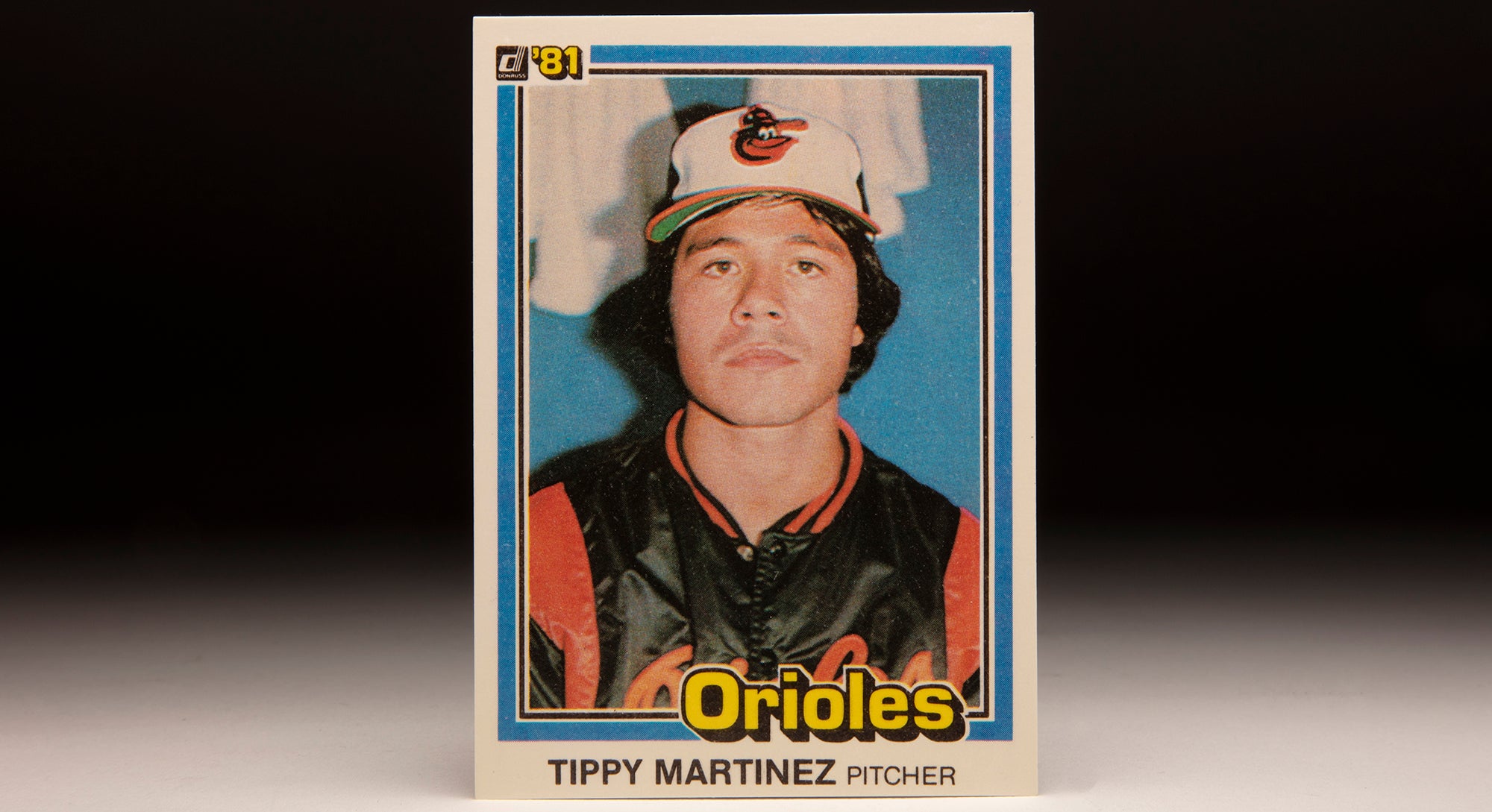

It would be as close as Kelly would get to a World Series ring. But in the tight-knit Orioles clubhouse, Kelly continued to be one of the veteran leaders. He began sharing his faith journey and eventually found like-minded teammates like Tippy Martinez and Scott McGregor.

“I got saved in 1978 through (Kelly’s) influence,” McGregor told the Evening Sun.

Not everybody, however, was influenced, including Weaver. Kelly often told the story of how he would encourage the future Hall of Famer skipper to “walk with the Lord.”

Weaver would reply that he’d rather have Kelly “walk with the bases loaded.”

In 1980, Kelly hit .260 with 34 walks and 16 steals off the bench. The Orioles won 100 games but finished second in the AL East. Kelly became a free agent following the season and signed a two-year deal with Cleveland on Dec. 29, 1980.

In his four seasons in Baltimore, the Orioles averaged better than 97 wins per year.

“He’s the veteran left-handed hitter we were looking for,” Indians general manager Phil Seghi told the Associated Press.

Kelly appeared in 48 games in that strike-shortened season, batting .213 with a .333 OBP. On Oct. 2 against the Red Sox, he drew a bases-loaded walk in the seventh inning against Mark Clear that put Cleveland in front 5-4. The next inning, Kelly hit a three-run double off Bill Campbell to secure an 11-4 Indians win that knocked Boston out of the running for the second-half AL East title.

Kelly appeared in two more games off the bench against the Red Sox to end the season. On April 2, 1982, Cleveland released Kelly despite his guaranteed $125,000 salary. It was a move that ended Kelly’s playing career.

“You can’t play forever,” Kelly told the Cleveland Plain Dealer that spring when he was competing for a bench job with Karl Pagel. “I still have some hits left in me, but if something happens I will have no regrets. I’ve had a good and long career. When it is over, I probably will go to Bible college and preach the Lord’s word full-time.”

Following his playing career, Kelly became a minister and was ordained in 1986 at the Evangelical Baptist Church in Baltimore. He also worked for Christian Family Outreach, a nonprofit in Cleveland that served at-risk youth.

On Oct. 2, 2005, Kelly suffered a heart attack while traveling to Chambersburg, Pa., after preaching at a Methodist church in Amberson, Pa. He died that afternoon at age 61 in a Chambersburg hospital.

“He transcended race, class, sports, and was just a fabulous lover of people, a good husband and father,” Joe Ehrmann, a former defensive lineman with the Baltimore Colts and Detroit Lions who became a minister in Baltimore, told the Evening Sun following Kelly’s death. “He was a charismatic preacher whose message came from his own life, and he wanted people to know that he walked with God.”

Kelly finished his 15-year big league career with a .264 batting average, 588 walks (powering a .354 on-base percentage), 1,147 hits and 250 stolen bases. And though it was not the Hall of Fame career that his brother had, Kelly fulfilled his destiny as an athlete and a human being.

“I’m proud of my brother but I don’t feel any pressure because of his success,” Kelly told UPI in 1969 when he was getting his first taste of success in the big leagues. “It might be different if it was the same sport and I was following him into football. But since it’s a different sport, there’s no problem.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum