- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1981 Topps Bob Horner

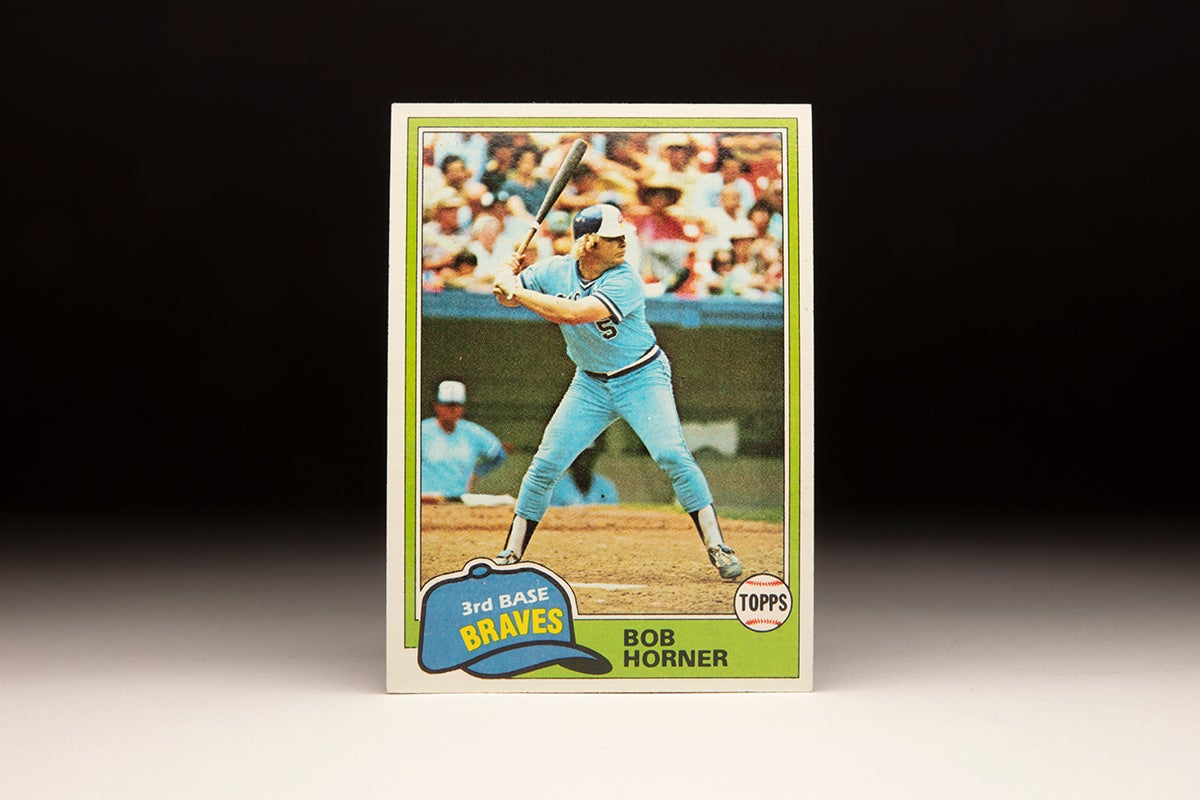

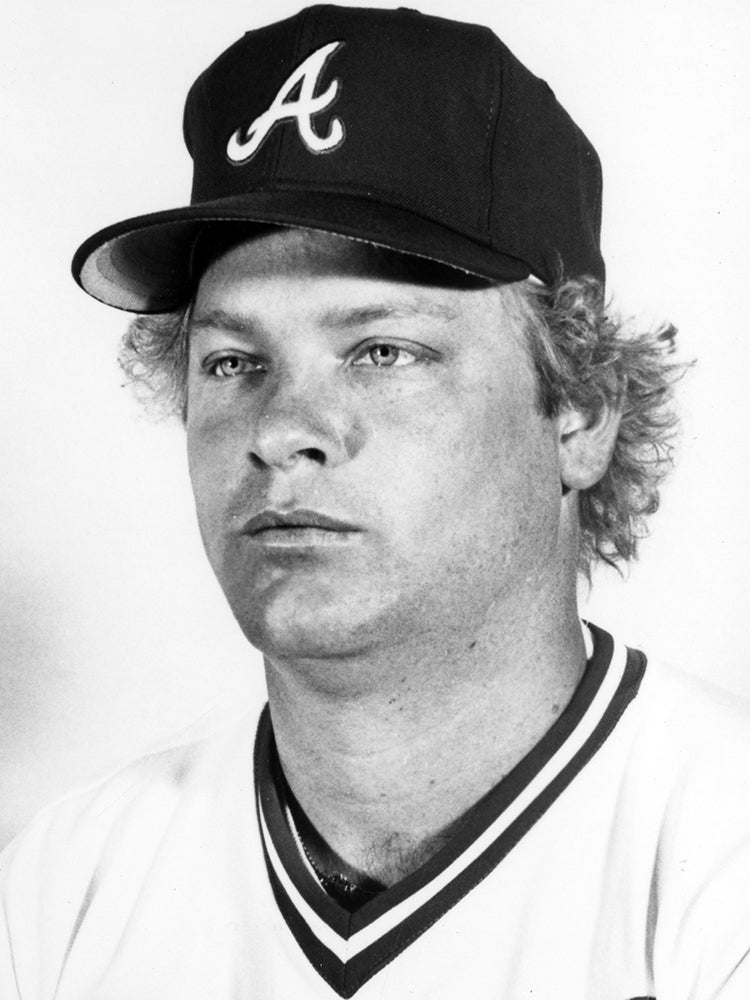

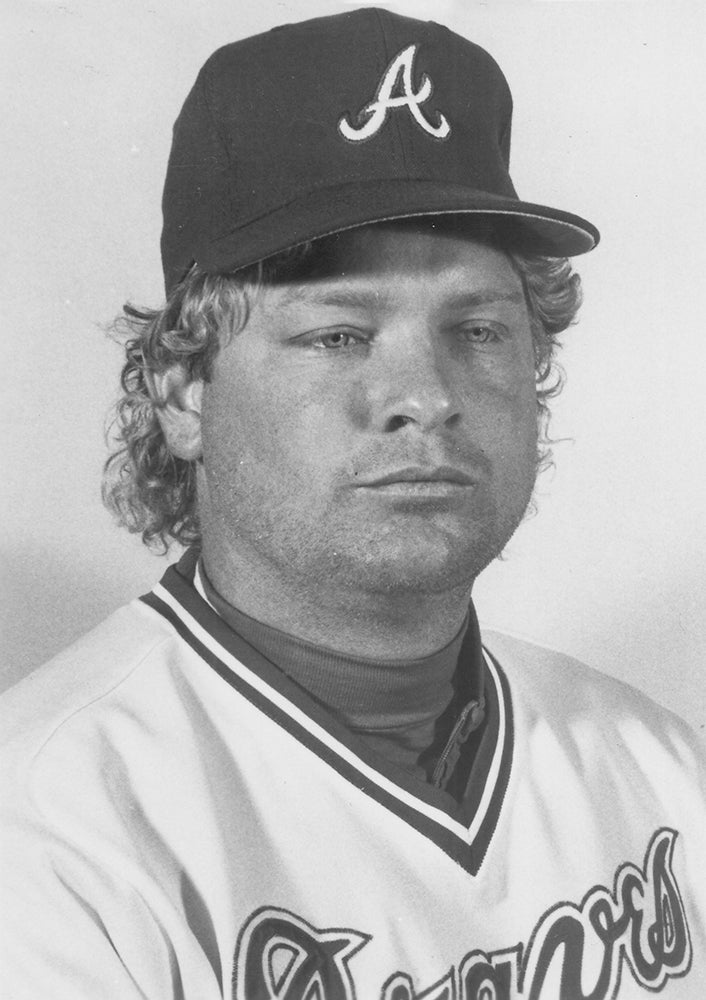

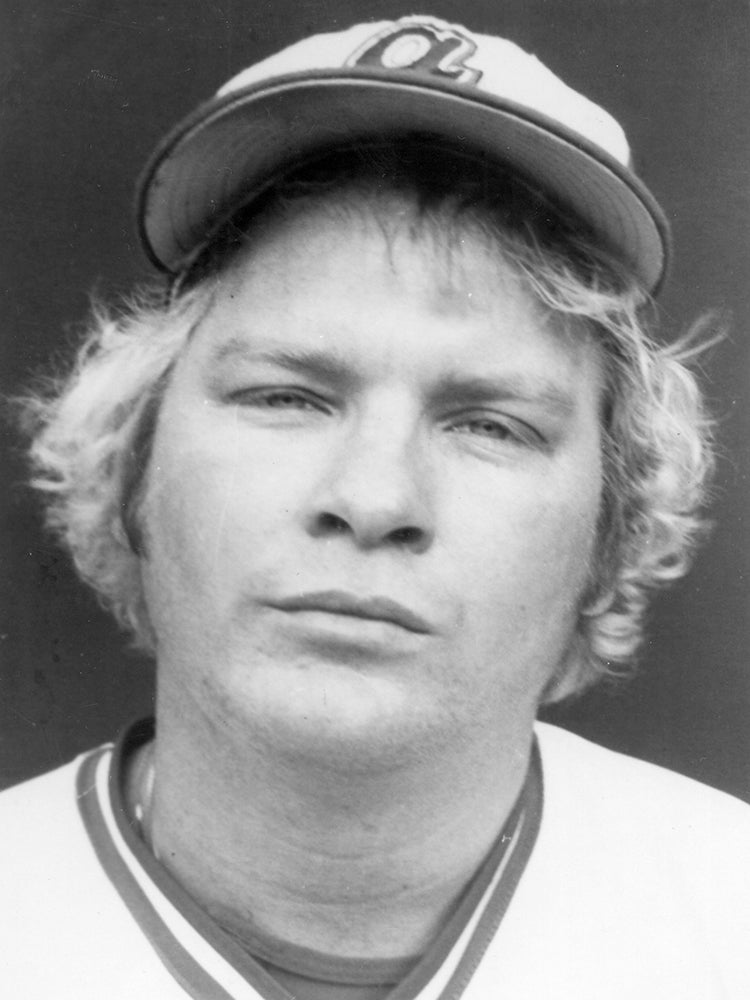

#CardCorner: 1981 Topps Bob Horner

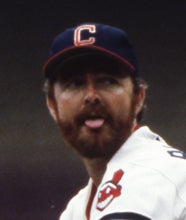

He was as much of a “can’t miss” prospect as there ever was in the 1970s, and Bob Horner jumped right from the campus of Arizona State University to the big leagues in June of 1978.

And though injuries shortened his career and prevented him from playing in more than 141 games in any of his 10 big league seasons, Horner still left his mark on the record books.

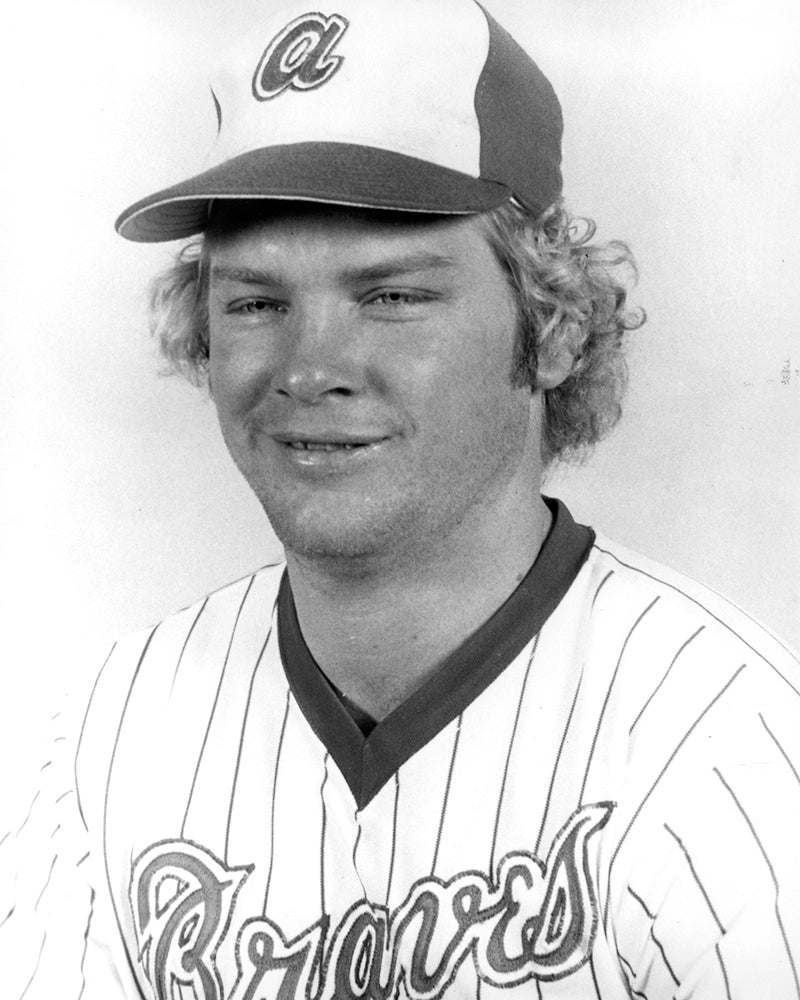

James Robert Horner was born Aug. 6, 1957, in Junction City, Kan., about 120 miles west of Kansas City. Horner’s father was in sales, and the family moved to California and then to Arizona when Bob was in his teens. He starred in both baseball and basketball at Apollo High School in Glendale, Ariz., teaming up often with his older brother, Gary.

After graduating in 1975, the Athletics took Horner in the 15th round of the MLB Draft. But Horner chose to go to college and enrolled at Arizona State University in Tempe. As a freshman, Horner was named to the All-Western Athletic Conference Southern Division All-Star team after hitting .352 with nine homers and 42 RBI.

As a sophomore in 1977, Horner led the nation with 22 homers, 87 RBI, 102 hits and 191 total bases. He won the Most Outstanding Player Award at the College World Series after leading Arizona State to its fourth national championship.

Then in his junior season, Horner hit .412 in 60 games with 25 homers and 100 RBI, setting NCAA Division I single-season records in the latter two categories. Arizona State advanced to the championship game of the College World Series before falling to Southern California in the final contest.

The Braves had the top pick in the 1978 MLB Draft, and Horner was the obvious choice. He signed with the Braves on June 14 and convinced the front office that he was ready for the big leagues at that point. Two days later, he made his debut against the Pirates at Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium, homering in his third at-bat against future Hall of Famer Bert Blyleven.

“You know, this is quite a step I’ve taken,” Horner told the Atlanta Constitution. “I guess I’ve got a lot to learn. It’s been three years since I’ve swung a wooden bat. It sure feels different.”

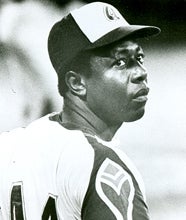

But from the start, even the game’s all-time home run leader knew Horner would adjust.

“This guy will be all right,” Hank Aaron told the Constitution. “You can tell by the way the ball leaves his bat. It’s whistling.”

Horner was hitting just .173 at the end of June but stayed in the lineup at third base as manager Bobby Cox committed to the Braves’ youth movement. In July, Horner hit .321 with seven homers and 20 RBI and continued to pound the ball the rest of the season, finishing with a .266 batting average, 23 homers and 63 RBI in 89 games.

“I just think (Horner has) a super future ahead of him,” Cox told the Associated Press. “He will be capable of winning the RBI and home run titles in the future, and he’s a good third baseman. He can carry the Braves for some years to come.”

Following the season, Horner was named the National League Rookie of the Year, edging out Ozzie Smith by four votes.

“What else can happen in a year? That caps off a year that I’ll probably never forget the rest of my life: Getting married, (Sporting News) College Player of the Year and Rookie of the Year,” Horner told the Associated Press. “That’s absolutely fantastic.”

Financially, it was also a banner year for Horner. He received a $150,000 bonus from the Braves along with $5,000 for his education and a contract worth $21,000 for 1978 – which would be prorated to about $13,000 since he didn’t debut until June.

Prior to the 1979 campaign, Horner’s agent, Bucky Woy, asked for a raise for his client – basing his starting point off the fact that Horner received $168,000 in 1978 due to his salary and bonuses. His asking price: A three-year deal worth $1 million. Woy claimed that Braves general manager Bill Lucas later agreed to a two-year deal worth about $300,000 per season but backed out, leaving Woy to demand that Horner be declared a free agent.

“Bob is a pretty good kid,” Lucas told United Press International. “I don’t care that much what Woy says because he’s not going to play for us…what hurts most is the feeling (Horner) is developing toward an organization that was very decent to him.”

The case eventually was decided by an arbitrator who denied the free agency request but ruled that Horner’s contract for 1979 would be worth $146,000.

“I’m happy, relieved, upset and miserable all at once,” Horner told the Associated Press after the conclusion of a salary dispute that lasted six months. “I’ll just pick up the pieces and go from here.”

Horner had stayed away from Spring Training until just before the 1979 opener while the dispute dragged on. On Opening Day, he injured his ankle, sidelining him for six weeks. When he returned, he hit better than he had in his rookie season – finishing with a .314 batting average, 33 home runs and 98 RBI in 121 games.

He also struck out remarkably few times for a power hitter, fanning in just 74 of his 515 plate appearances. During his career, Horner never appeared in the Top 10 of the NL strikeout leaders in any season.

“I’ve never seen anyone like him,” Cubs manager Herman Franks told the Atlanta Journal. “You don’t see him get fooled much. He doesn’t go after bad pitches.”

Braves owner Ted Turner rewarded Horner with a three-year deal worth $1 million. But in the Braves’ first 10 games in 1980, Horner went 2-for-34 (.059) with six errors. Turner then ordered general manager John Mullen to send Horner to Triple-A Richmond.

Horner refused and left the team.

“I’m willing to sit out as long as I have to and forfeit as much money as need be to get the Braves to trade me,” Horner told the media. “If I felt there was any justification for being sent down to the minors, I would go. But when everyone calls me – fans, friends, teammates, people in the front office – and tells me it’s just Ted going a little whacko again, it confirms what I already know: Ted Turner is a jerk, an absolute jerk.”

With the player/team relationship damaged, Turner tried to smooth things over when Horner returned to the team in early May.

“I didn’t want to punish Bob,” Turner told the media. “That’s ridiculous. If I was vindictive, why did I give him a three-year, $1 million contract? I thought I was doing Bob a favor by sending him down. He was being booed unmercifully and was under a lot of pressure.”

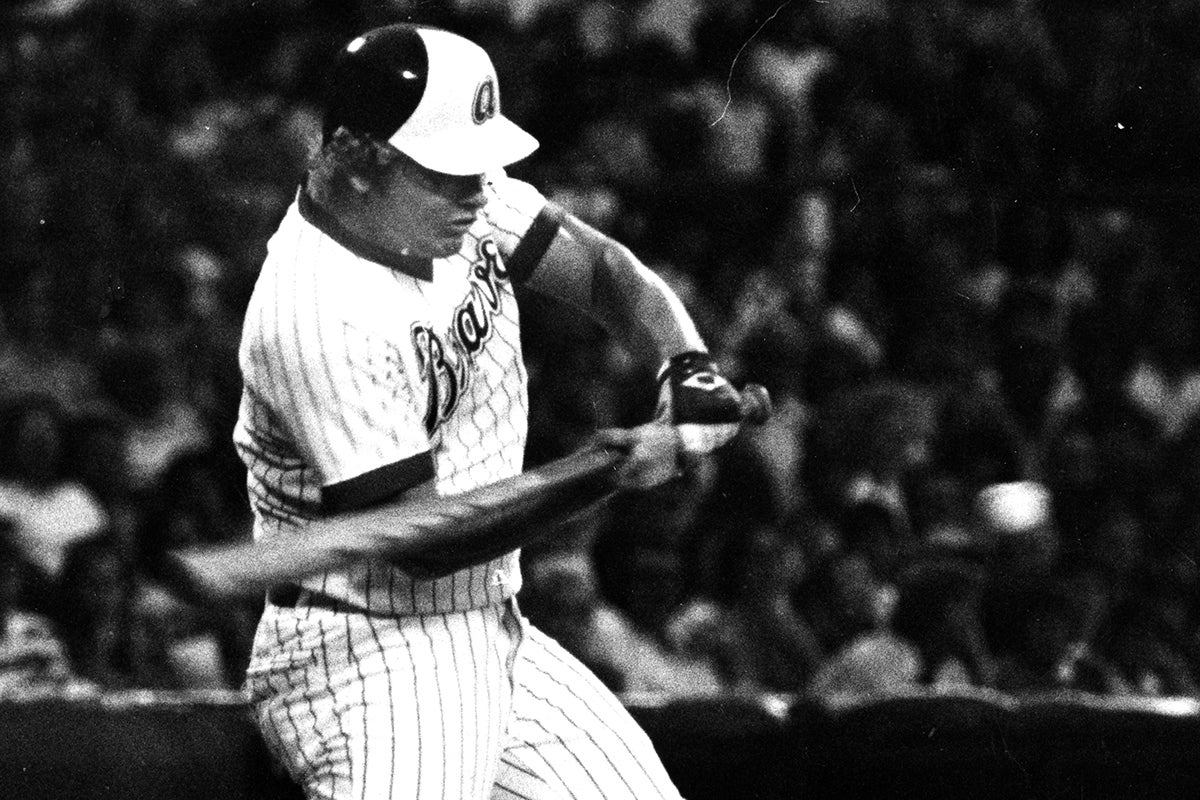

Horner appeared in just 124 games in 1980 – missing some time with injuries in addition to his conflict with the team – but by many measures had the best season of his career. He batted .268 with 35 home runs and 89 RBI, posting a career-high 4.4 WAR and finishing a career-best ninth in the NL Most Valuable Player Award voting. In July alone, Horner hit 14 homers and drove in 32 runs over 29 games to earn NL Player of the Month honors.

Few in baseball thought there was a more powerful hitter than Horner.

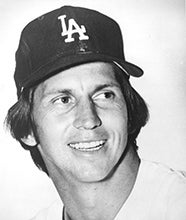

“If Bob Horner plays 162 games,” future Hall of Fame pitcher Don Sutton told Field News Service, “he’s going to hit 60 home runs.”

Horner hit 15 home runs in 79 games in the strike-shortened 1981 campaign. Then in 1982, Horner helped the Braves win their first NL West title since 1969 when he belted 32 home runs and drove in 97 runs – teaming with Dale Murphy to form one of the top power duos in the big leagues and earning the only All-Star Game selection of his career.

But in his first taste of postseason play, Horner had just one hit (a single) in 11 at-bats as the Cardinals swept the NLCS to advance to the World Series.

The 6-foot-1 Horner, who weighed a reported 237 pounds at the end of the 1982 season, dedicated himself to a fitness routine in the offseason and reported to camp in 1983 a svelte 21 pounds lighter. He also had motivation in the form of money: As part of the four-year, $5.5 million deal he signed in January of 1983 – which at the time was the most money ever given to a player who was 25-or-younger – Horner agreed to 13 weigh-ins throughout the year before Friday home games. Horner would receive a bonus of $7,692.31 for each time he weighed 215 or less.

The Braves also worked out Horner in left field in the spring of 1983. Though he committed just 10 errors in 137 games at third base the year before, his lack of range left him with a Defensive WAR of -1.2.

“I could do it,” Horner told the AP of his potential move to left field. “It’s just a matter of taking about 150 fly balls daily out there for a while.”

But except for one game at first base, Horner played all 104 of his contests at third in 1983. But while he made weight in each of his weigh-ins, he was sidelined for the final month-and-a-half of the season when he broke his right wrist while trying to break up a double play on Aug. 15. At the time, Horner was batting .303 with 20 homers and 68 RBI, putting him on pace for his best season.

“The first thing that hit me last night was (the possibility that the Braves might make the postseason again and he would miss it),” Horner told the AP after the injury. “To get this far, then have this happen…that hurts. I don’t even want to think about it.”

The pain got worse for Horner in 1984. He missed 16 games at the start of May with a separated left shoulder. When he returned, he was hitting .274 with 19 RBI in 32 games when he rebroke the navicular bone in his right wrist, ending his season prematurely again. The injury occurred when he dove for a ball near the Braves dugout in a game against Chicago on May 29.

“I’m out of excuses. I’m out of answers,” Horner told the AP. “I have no idea why this happens. Maybe it just wasn’t meant to be. Maybe I shouldn’t have been a player. I’m at the end of my rope.

“I don’t think this will make my career stop. That’s my only condolence.”

Horner used his time on the sidelines to build up his investment portfolio, sinking dollars into oil, land and a chain of restaurants that turned very profitable. He also worked hard on his recovery and beat projections by about a month by returning to the Braves’ lineup on Opening Day 1985 following bone graft surgery on his wrist on Dec. 18, 1984.

“Everybody in Atlanta wonders the same thing,” Braves broadcaster Pete Van Wieren told Gannett News Service. “What would happen if Bob was healthy for a full season?”

Horner was largely healthy in 1985 and hit .267 with 27 home runs and 89 RBI. But in the spring of 1986, Horner once again had contract issues with the Braves when his agent intimated that Horner might leave Atlanta as a free agent when his deal expired at the end of the season.

“If the Braves have a lousy year, then I think that’s it,” Horner’s agent Bucky Woy told the AP in the spring of 1986. “People shouldn’t take that as an ultimatum because it’s just a personal thing: Bob’s dying to play for a winner.”

Horner was also dealing with the fact that his younger brother, Scott, had been diagnosed with leukemia. Horner donated blood marrow to help his brother’s recovery.

“I’m not disappointed at all in my career,” Horner told the Cleveland Plain Dealer in 1986. “I’ve had my share of decent years.”

On Aug. 11, Scott Horner passed away due to leukemia.

“What I’ve been trying to do is concentrate on my job, but there’s no way you can put something like this out of your mind,” Horner told the Los Angeles Times. “It’s hard to describe. Between the chemotherapy and…well, it’s been a hell of a thing that Scott has had to go through.

“It’s life. Nobody said life was going to be easy.”

Horner played in what turned out to be a career-high 141 games in 1986, batting .273 with 27 home runs and 87 RBI. After playing 87 games at first base in 1985, the Braves moved Horner to first permanently in 1986. It was also the season that he joined one of baseball’s most exclusive clubs when he hit four home runs on July 6 against the Expos, becoming just the 11th AL or NL player to reach that mark and the first in a nine-inning game since Willie Mays in 1961.

“I had a good week today,” Horner told the AP after the game. “It’s just one of those things that happen and you can’t explain it.”

But the Braves lost that game 11-8 – the third of what became 11 losses in 12 games in a season where Atlanta went 72-89. It was the sixth time in Horner’s nine seasons that the Braves finished under .500.

Horner became a free agent after the season when he turned down a Braves offer reported to be worth $4.5 million over three years. The Braves were operating under MLB rules that stated that if a free agent did not re-sign with his club by Jan. 8, the free agent could not then sign with his old team until May 1. The deadline came and went, forcing Horner to look elsewhere.

But during a winter where it was eventually ruled that the owners colluded to keep salaries in check, few offers were forthcoming. The Rangers and Horner’s agent, Bucky Woy, negotiated for a while in March but could not come to an agreement.

“If money is an issue, I tried to eliminate that,” Woy told the Fort Worth Star-Telegram during a time when Horner, who lived in Dallas, let it be known that he’d play for the Rangers for less money than for other teams. “We’ll take a big pay cut. I haven’t been in a position to say $600,000 or $800,000, but there hasn’t been any interest.”

Horner and Woy eventually decided that MLB was not their best option and signed a one-year deal worth $1.3 million with the Yakult Swallows of the Japan Central League – a deal that included money for Horner’s living expenses.

“It was too good to pass up,” Woy told USA Today.

In 93 games with Yakult, Horner hit .327 with 31 homers and 73 RBI – good for a .683 slugging percentage. But Horner was ready to return to the United States after the season and turned down a $10 million contract offer from the Swallows.

The Braves offered Horner a one-year deal worth $900,000 but it proved far less than acceptable.

“I don’t see any other team that is going to offer Bob what we offered,” Braves general manager Bobby Cox told the AP. “We were up front. We didn’t start low then work up to it.”

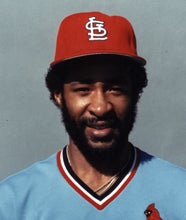

On Jan. 14, 1988, Horner signed a one-year deal worth $950,000 (plus incentives) with the Cardinals.

“It’s been a dream of mine to play for the Cardinals,” Horner told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. “What an absolutely perfect fit.”

But Horner didn’t reach any of his incentives. He injured his left shoulder in June and underwent arthroscopic surgery, sidelining him for the rest of the season. In 60 games, he hit .257 with three homers and 33 RBI.

Horner reported to camp with the Orioles in the spring of 1989 with a good chance to earn a roster spot. But with the cartilage in his left shoulder nearly gone, Horner retired on March 9.

“I felt in my heart it was over,” Horner told the Post-Dispatch. “I wanted to go home, wanted to relax. Sure, I miss it from time to time. But I’m not bitter. I’ve had my day in the sun.”

Horner finished his career with a .277 batting average, 218 home runs and an .839 OPS. Over 10 seasons in the big leagues, he struck out just 512 times.

“Put a wood bat in his hands, and he would hit it,” Cox told the Post-Dispatch after Horner retired. “He was a natural, a true professional. Give him all those at-bats back (if he wasn’t injured), and you’re talking about a guy who could have hit 400 home runs.”

But even without 400 home runs, Horner’s legacy was secured when he was among the first 10 honorees at the inaugural College Baseball Hall of Fame induction in 2006.

“Nobody’s ever come straight into the majors and done what he did,” Braves owner Ted Turner said after the 1978 season. “So all he is, is the best there ever was.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum