- Home

- Our Stories

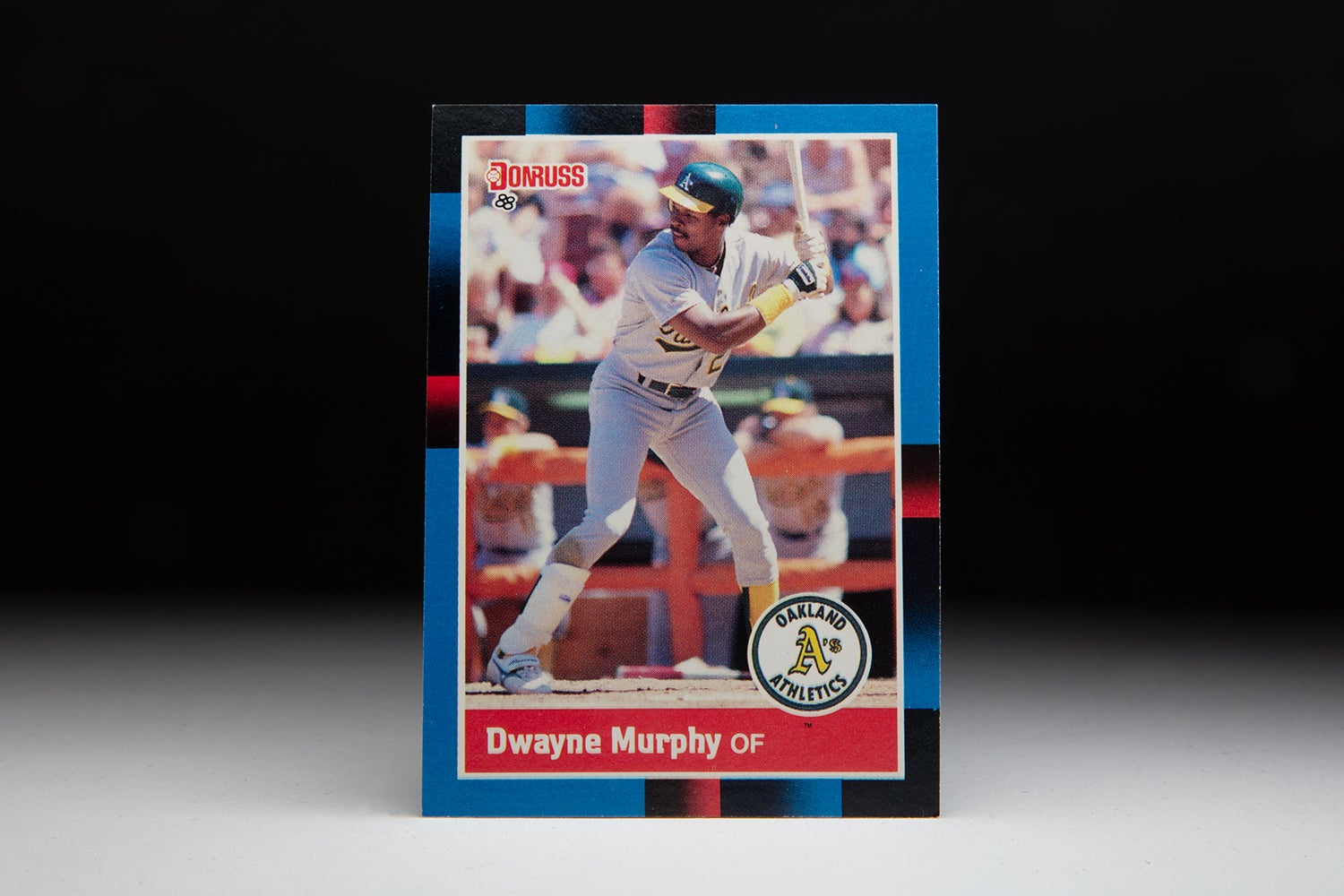

- #CardCorner: 1988 Donruss Dwayne Murphy

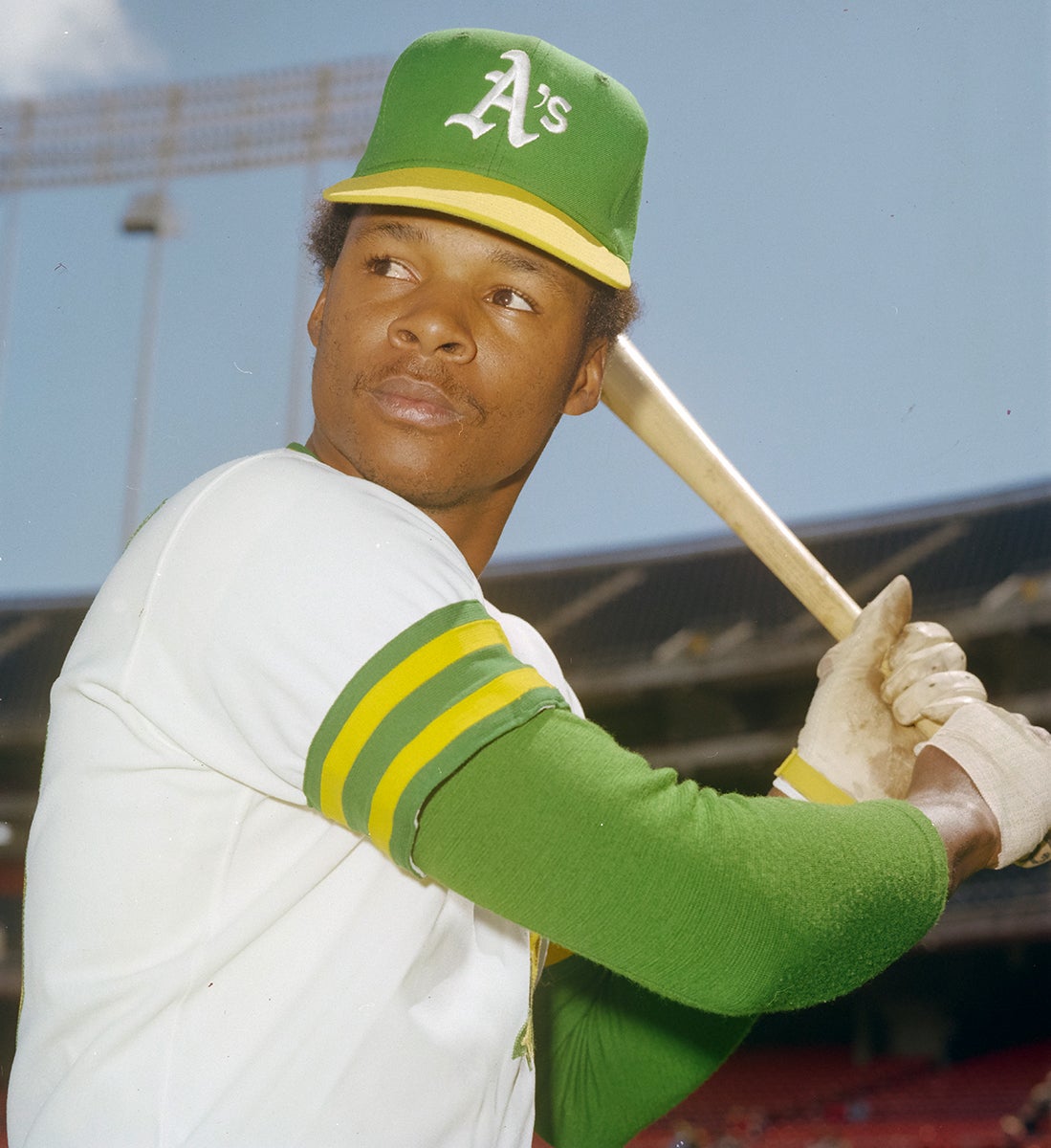

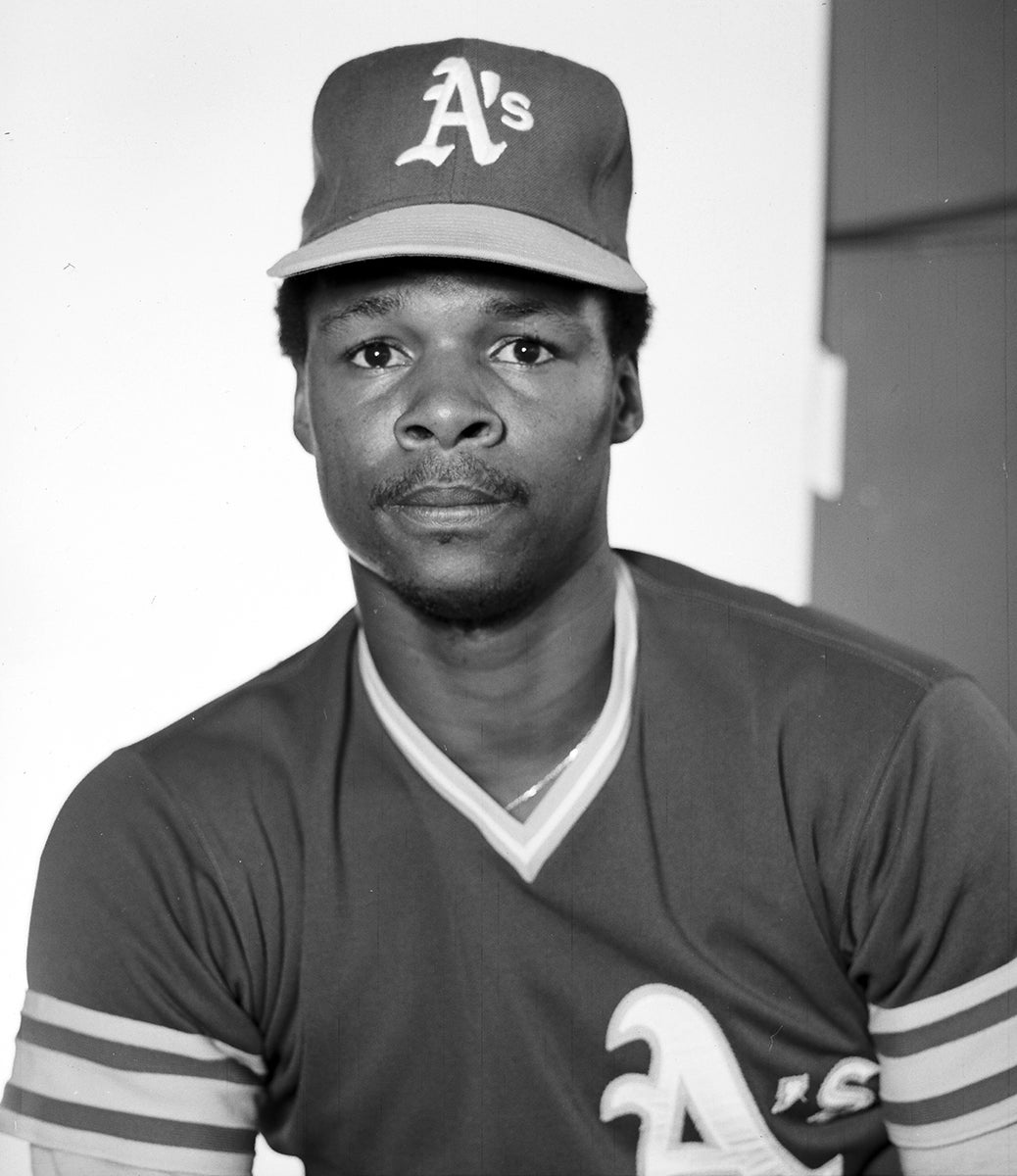

#CardCorner: 1988 Donruss Dwayne Murphy

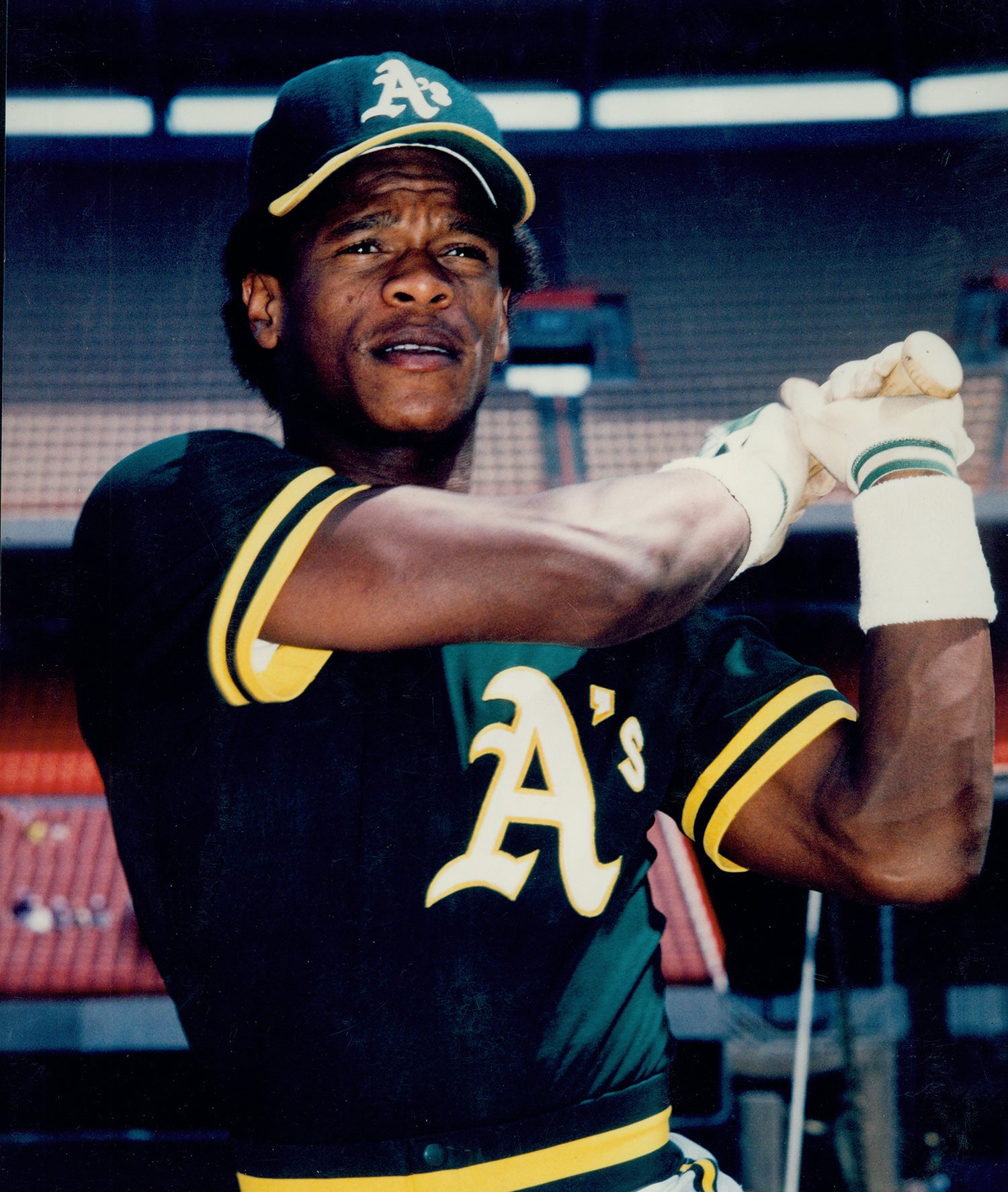

He was a power-hitting center fielder with a strong command of the strike zone and six Gold Glove Awards on his resume.

But Dwayne Murphy’s best years fell between the Oakland Athletics’ dynasties of the 1970s and 1980s. As a result, Murphy is often unfairly overlooked as one of the best of his era at his position.

Dwayne Keith Murphy was born March 18, 1955, in Merced, Calif. Growing up in Lancaster, Calif., on the western edge of the Mohave Desert north of Los Angeles, Murphy was a shortstop in high school. But his real passion was football, where he was a standout running back and defensive back for Antelope Valley High School was offered a scholarship to Arizona State University.

In the spring of his senior year in 1973, Murphy and his wife Brenda welcomed son Dwayne Jr. into the world. Murphy decided then to turn to baseball, accepting a $6,500 bonus from the Athletics when the selected him in the 15th round of the June MLB Draft.

“I had a letter from every college there was,” Murphy told the Los Angeles Times after his playing career had ended. “But I never got any scholarship offers for baseball.

“Hey, back in ’73 ($6,500) wasn’t too bad.”

The A’s send Murphy to Lewiston of the Northwest League, where he hit .233 with 14 steals in 68 games but also looked out of place at shortstop.

“I remember he wasn’t that great a shortstop,” pitcher Steve McCatty, who went on to a nine-year career with Oakland, told the Los Angeles Times. “I won’t say he threw balls over the wall and into the stands, but the coaches saw him play for a little while and said: ‘OK, that’s enough. Get to the outfield.”

In 1974, Murphy moved up to Class A Burlington of the Midwest League, where he hit .220. Then in 1975, he established himself as a big league prospect by hitting .291 with 20 doubles, 71 RBI and 37 steals while posting a .400 on-base percentage.

He split the 1976 season between Double-A and Triple-A, hitting just .248 but stealing 33 bases and drawing 87 walks. He returned to Double-A Chattanooga in 1977, this time drawing 97 walks in 132 games. With A’s owner Charlie Finley watching the stars from his 1972-74 World Series champions leaving via free agency, Murphy and his minor league teammates had a unique chance to climb to the big leagues.

In 1978, Murphy made Oakland’s Opening Day roster.

“I can remember we opened up in Anaheim in ’78, and I was in awe,” Murphy told the Los Angeles Times.

Murphy made his big league debut in the second game of that season as a defensive replacement, started his first game on April 29 (going 0-for-2 with three walks and two runs scored as the center fielder in a 5-1 win over Cleveland) and recording his first hit May 12 against the Tigers. He was eventually sent to Triple-A Vancouver for more seasoning and finished the year with a .192 batting average over 62 plate appearances in 60 games with Oakland.

The Athletics fully embraced a youth movement in 1979, with Murphy ensconced in center field for most of the year. In 121 games, Murphy hit .255 while drawing 84 walks for a .387 on-base percentage. He was joined in the outfield midway through the season by Rickey Henderson, giving Oakland one of the fastest fly-catching tandems in the game.

The A’s suffered through 108 losses but Murphy quickly evolved into one of the team leaders, rallying around struggling pitchers like Matt Keough, who opened the campaign with an 0-14 record. Murphy drove in four runs as Keough snapped his skid with a 6-1 complete game win over the Brewers on Sept. 5 in front of an announced crowd of 1,772 fans at Oakland-Alameda County Coliseum.

“I thought before the game I had to do something to win it for Keough,” Murphy told United Press International. “He’s had some bad luck.”

Murphy, Keough and the A’s had fortune smile upon them, however, when Finley hired Billy Martin as manager for the 1980 season. With a young, talented outfield of Murphy, Henderson and Tony Armas – and a five-man rotation of Rick Langford, Mike Norris, Brian Kingman, McCatty and Keough starting all but three of Oakland’s contests and totaling 93 complete games – the A’s improved by 29 games.

Murphy hit .274 with 13 homers, 68 RBI, 26 steals and 102 walks while becoming one of the best outfield defenders in baseball. His 501 putouts led all of baseball – and the total remains one of only six seasons in history where a center fielder recorded at least 500 putouts. Hall of Famer Richie Ashburn has three of those seasons, with Taylor Douthit and Chet Lemon claiming the other two.

For his efforts, Murphy won the first of his six straight Gold Glove Awards.

“Me and Billy clicked real well,” Murphy told the Los Angeles Times of his days with Billy Martin as manager. “He taught me how to run the outfield, and I think that’s what made our outfield so good.”

In 1981, the A’s became the talk of baseball by winning their first 11 games en route to a 24-6 mark in early May. The six losses at that point were all by two-or-fewer runs (four of them coming by one run), and Oakland seemed to be on the way to a historic season before the strike interrupted play in June.

When play resumed, the A’s and the other division leaders at the time of the strike were declared first half champions and automatically qualified for the postseason. But without much motivation to win, the A’s still went 27-22 in the second half, finishing with 64 wins, second to only the Reds’ 66 victories (Cincinnati famously did not win either the first or second half division title and therefore missed the playoffs).

Murphy hit .251 with 15 homers, 60 RBI and 73 walks in 107 games. He had two hits apiece in each of Oakland’s three games in a sweep of Kansas City in the ALDS, scoring both of the Athletics’ runs in a 2-1 win in Game 2 and thrusting himself into the national spotlight.

The A’s were swept out of the ALCS by the Yankees, however, and Murphy injured a rib cage ligament while swinging the bat in his first plate appearance in Game 3 and was forced to leave the game. But the future seemed very bright for a team that only two years before had won just 54 games.

“Billy (Martin) helped make (Murphy) a better outfielder and he made me a better pitcher,” said McCatty, a pitch-to-contact hurler who led the AL in ERA (2.33), shutouts (4) and wins (tied with 14) in 1981 while finishing second in the AL Cy Young Award voting. “Murphy made the plays that made me look so good, as did (Rickey Henderson) and (Tony Armas). I used to say we should move the wall back so more balls would fall in for them to catch.”

But the 1981 season would be the apex for that Oakland team. Martin, as would be the case often throughout his career, feuded with management as the A’s went 68-94 in 1982. The team drew a Coliseum-record 1.735 million fans who came to love what was termed “Billy Ball” – but A’s president Roy Eisenhardt dismissed Martin on Oct. 20.

Murphy, however, had his best season to date that year, hitting 27 homers to go with 94 RBI, 26 steals and 94 walks while taking countless pitches to help Henderson steal what would become – and remains – the all-time single-season record of 130. Henderson credited Murphy throughout the season for helping him reach the record.

But Murphy, the A’s team captain, knew that Martin – whose full three-year tenure with Oakland was the longest continuous stretch of his MLB managerial career – was likely not to return in 1983.

“The whole club knew,” Murphy told the Associated Press about Martin’s battles with the Athletics’ front office. “We didn’t know the details but we had a pretty good idea what was going on.”

Murphy, however, became rooted in Oakland after signing a four-year deal worth a reported $3.3 million in January of 1983. It brought to a close several months of rumors that bandied the possibility of Murphy being traded.

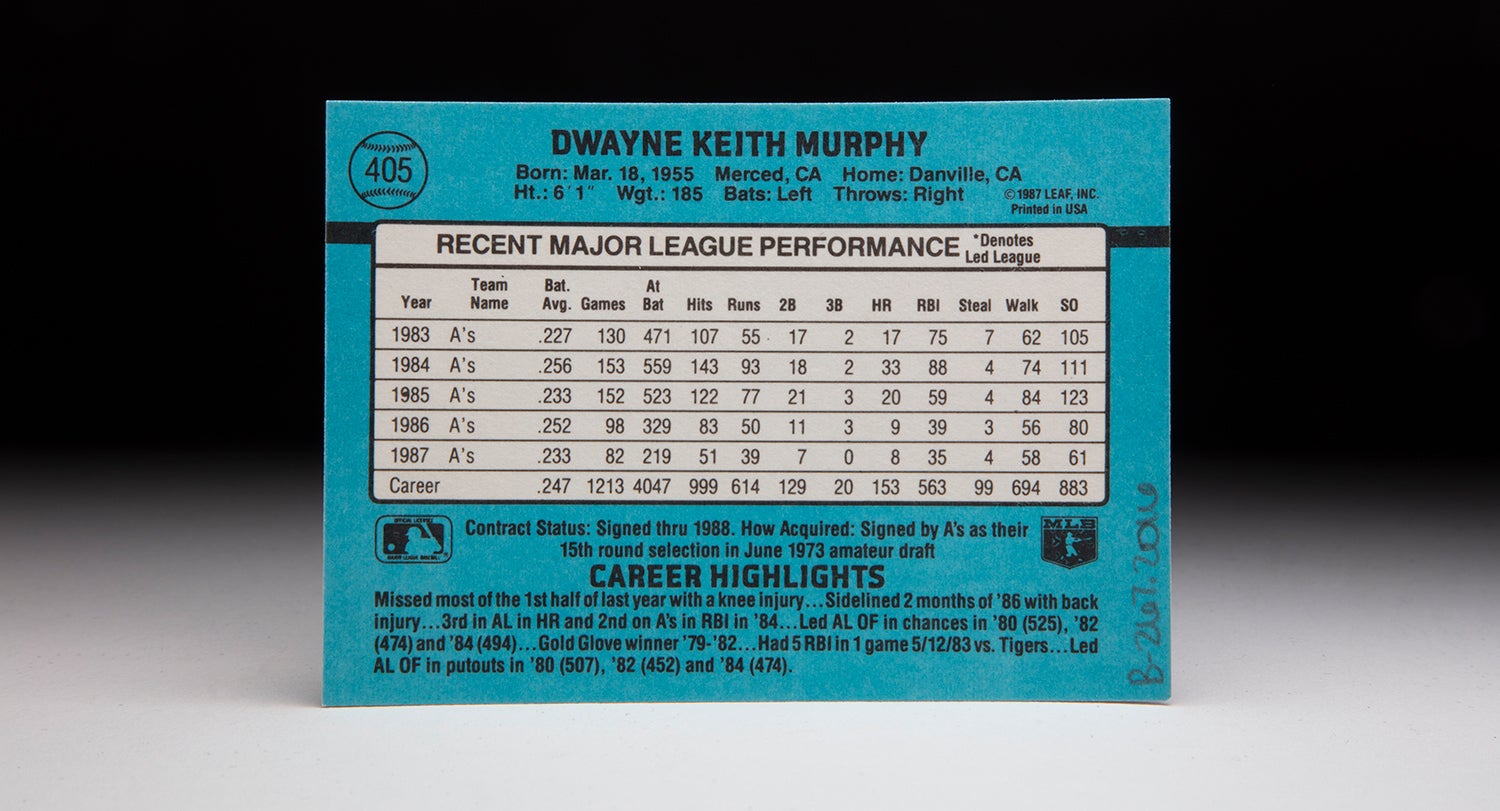

Murphy was unable to find a groove at the plate in 1983, hitting .196 as late as May 30 and finishing with a .227 average, 17 homers and 75 RBI. But in 1984, Murphy roared back with 33 homers, 88 RBI, 93 runs scored and 74 walks while leading AL outfielders in putouts for the third time in five seasons.

The A’s, however, posted their third straight losing season.

The 1985 campaign would mark the last season for Murphy as a big league regular as he hit .233 with 20 homers, 59 RBI and 84 walks. The foundation for the Athletics’ next dynasty was laid when Tony La Russa took over as manager during the 1986 season but by then Murphy had endured several weeks on the disabled list after running into the left field wall at Fenway Park in May and rupturing a disc in his back. He played in just 98 games that year, hitting .252 as his streak of six straight Gold Glove Award-winning seasons came to an end.

Then on April 22, 1987, Murphy collided with teammate Mike Davis while chasing a ball hit by the Angels’ Gary Pettis. Both players had to be helped from the field, and Pettis circled the bases for an inside-the-park home run.

The right knee injury sustained by Murphy sidelined him for two months. He worked his way back into the lineup and was in center field for most of August and September, finishing the year with a .233 average in 82 games.

Following the season, the A’s declined to offer Murphy arbitration, making him a free agent. Under the rules at the time, Murphy could not sign with the A’s before May 1, 1988, even if the club wanted him back. He found few offers during what an arbitrator later ruled as collusion, and – after playing with an independent California League team in Fresno, Calif., Murphy signed a minor league deal with the Tigers on June 5. He appeared in 51 games for Triple-A Toledo before joining Detroit in late July, spending much of the rest of the season as the Tigers’ center fielder.

The A’s, meanwhile, won the first of three straight AL West titles that year.

After hitting .250 in 49 games with Detroit, Murphy got a look the following spring before the Tigers released him on March 27, 1989. He quickly signed with the Phillies and hit .218 off the bench that year in 98 games before drawing his release in November – a move that proved to be the end of his big league career.

After playing in Japan in 1990, knee troubles forced Murphy into retirement. But while relaxing at his home in Danville, Calif. (just outside Oakland), Murphy was offered the job as a freshman football coach in nearby San Ramon. He became the varsity head coach at San Ramon’s California High School two years later.

“Football was a big part of my life at (Antelope Valley High School),” Murphy told the Los Angeles Times. “I felt I was coached well and I learned a lot.

“I’m satisfied with my baseball career and I’m enjoying what I’m doing right now.”

But Murphy had a second baseball career as a coach yet to come. He joined the expansion Arizona Diamondbacks in 1996 and became their inaugural first base coach in 1998 before moving to the team’s hitting coach position in 2001, where he helped the team win the World Series title. He remained with the club through 2003 before joining the Blue Jays organization, where he worked in the minor leagues before becoming the team’s first base coach in 2008. He served as the club’s hitting instructor from 2010-12 then returning to the first base coaching box in 2013 and later worked with the Rangers.

“A lot of times I let (players) dictate what they want,” Murphy told the Arizona Republic of his coaching style. “I don’t try to lead one way. It may not be good for one person.”

Murphy finished his 12-year playing career with a .246 batting average, a .356 on-base percentage, 166 homers, 100 steals and 747 walks. His 3.13 range factor per nine innings as an outfielder ranks first all-time, ahead of such fielding stalwarts as Paul Blair, César Gerónimo and Garry Maddox.

Murphy is also the only A’s player with at least 1,000 games played in the 1970s or 1980s who was not part of at least one A’s World Series winner.

“It’s something you really work for your entire career,” Murphy told the Los Angeles Times about Oakland’s 1981 season. “Some guys play all those years and never get to see it. You play all those years and that’s what it’s all about.

“You come off a successful season, you sniff a piece of it, and we never quite got back.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum