- Home

- Our Stories

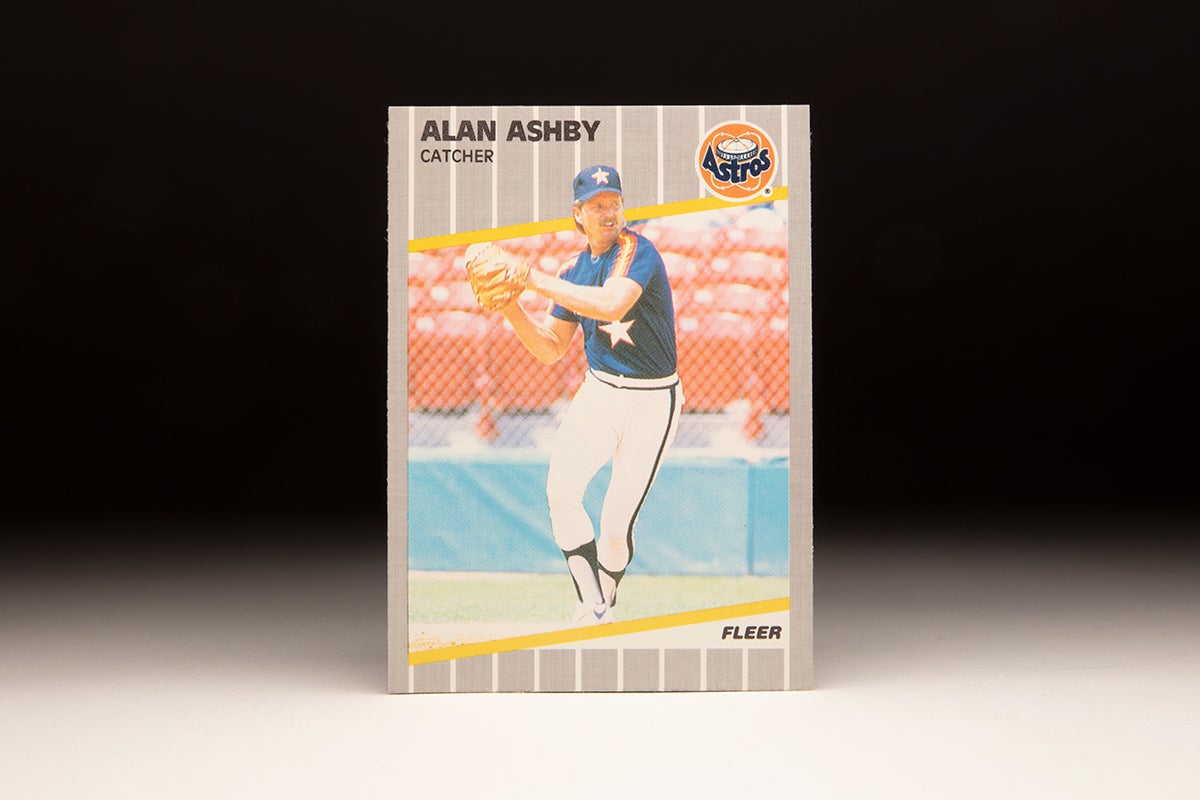

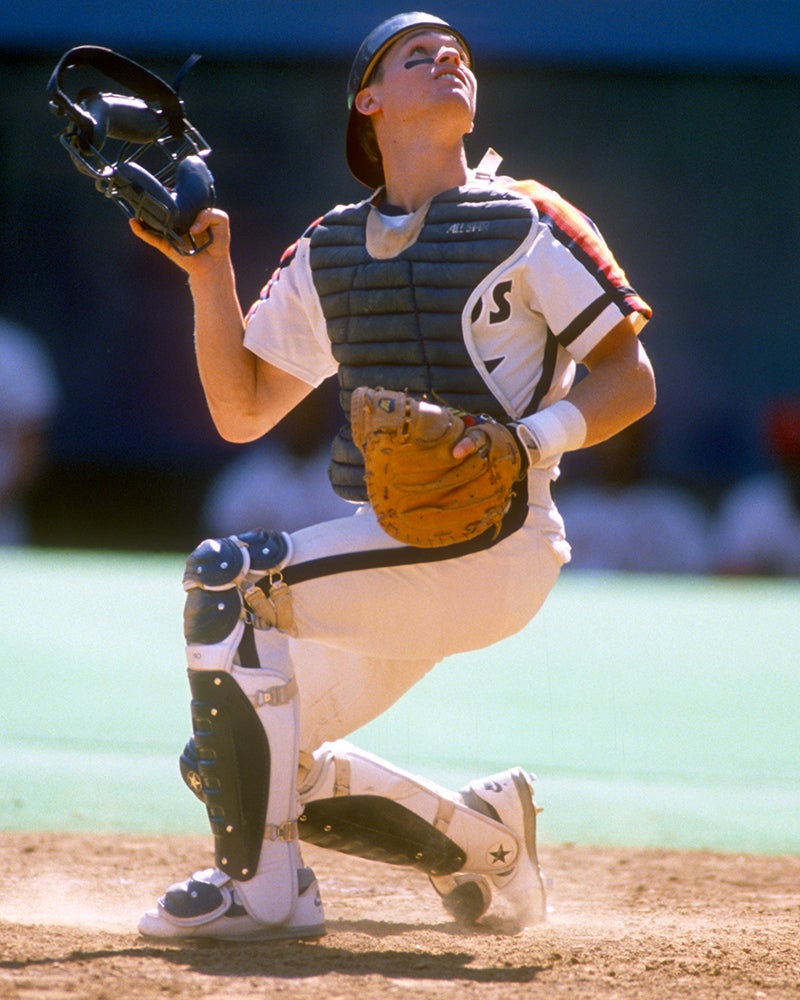

- #CardCorner: 1989 Fleer Alan Ashby

#CardCorner: 1989 Fleer Alan Ashby

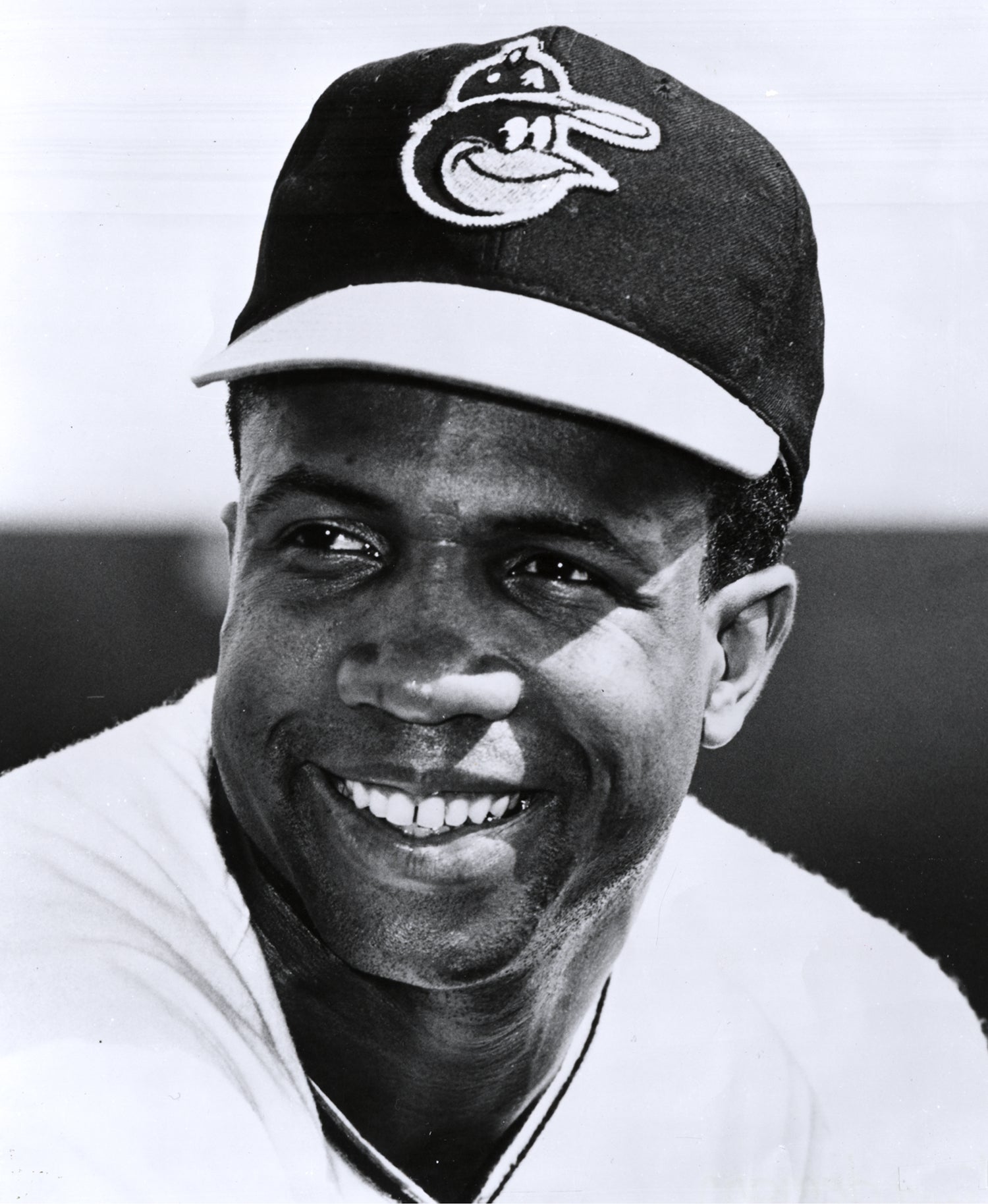

Alan Ashby caught for 17 big league seasons, seemingly defying time by improving with the bat deep into his 30s.

Experience may have been Ashby’s greatest teacher – as he was on the receiving end of offerings from some of the hardest-to-hit pitchers of his era.

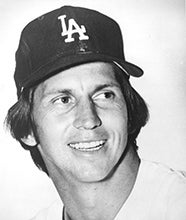

Born July 8, 1951, in Long Beach, Calif., Ashby grew up a Los Angeles Dodgers fan and began switch-hitting to emulate LA’s all-switch-hit infield of Wes Parker, Jim Lefebvre, Maury Wills and Jim Gilliam. An infielder and pitcher for most of his youth league days, Ashby converted to catcher for his senior year at San Pedro High School.

“He said he wanted to catch and even though he would have some competition, he felt he could win the job,” Ashby’s father, Roland, told the San Pedro News-Pilot in 1969. “So he went out to Long Beach and got a good glove and caught every game for San Pedro this year.”

With dreams of reaching the big leagues, Ashby believed catching was his ticket to the pros.

“If you don’t have speed, you don’t have much chance unless you are a pitcher or a catcher,” Ashby told the Nevada State Journal in 1971 when he was in the minor leagues.

Ashby was named the Marine League’s Player of the Year in 1969 after hitting .350 while throwing out all 23 runners that tried to steal on him. Cleveland selected Ashby in the third round of the 1969 MLB June Draft – high school teammate Garry Maddox had been drafted by the Giants in 1968 – and Ashby quickly signed a pro contract.

“He was the outstanding catcher in my area and no one even came close to him,” Indians scout Bob Nieman – a 12-year big league veteran – told the News-Pilot. “My area includes Southern California, Nevada and Arizona and no one matched Alan.

“This guy’s an accomplished catcher with a great arm. What’s even more amazing is that he’s only been catching one year.”

Ashby reported to Cleveland’s Gulf Coast League team in Sarasota, Fla., and hit .239 in 48 games while leading league catchers in fielding percentage with a .992 mark before playing for the organization’s Florida Instructional League team that fall.

In 1970, Ashby reported to the Class A Reno Silver Sox of the California League in late May and hit .190 over 40 games. He began the 1971 season at Double-A Jacksonville but was sent back to Reno after 13 games.

“I guess they wanted to get Larry Johnson (another of Cleveland’s catching prospects who would play a total of 12 games in the majors) and me apart and let us catch every day,” Ashby told the Nevada State Journal.

Ashby was one of the California League’s best hitters in 1971, batting .293 with 18 homers and 60 RBI in just 77 games en route to a 1.023 OPS. Cleveland promoted Ashby all the way to Triple-A in 1972, and he hit .223 in 95 games with the Beavers. But he was charged with only eight errors all season, solidifying his position as one of the top defensive catchers in the minor leagues.

The Indians brought Ashby to Spring Training in 1973 before sending him to Triple-A Oklahoma City. He was on loan to Milwaukee’s Triple-A team in Evansville when the Indians called him up to the majors in July.

“I almost passed out,” Ashby told the Associated Press of the moment he was told he was going to the big leagues.

Ashby debuted on July 3 as a ninth-inning defensive replacement against the Tigers at Cleveland Stadium. The next day, he started against the Tigers in Detroit and recorded an RBI single in his first plate appearance.

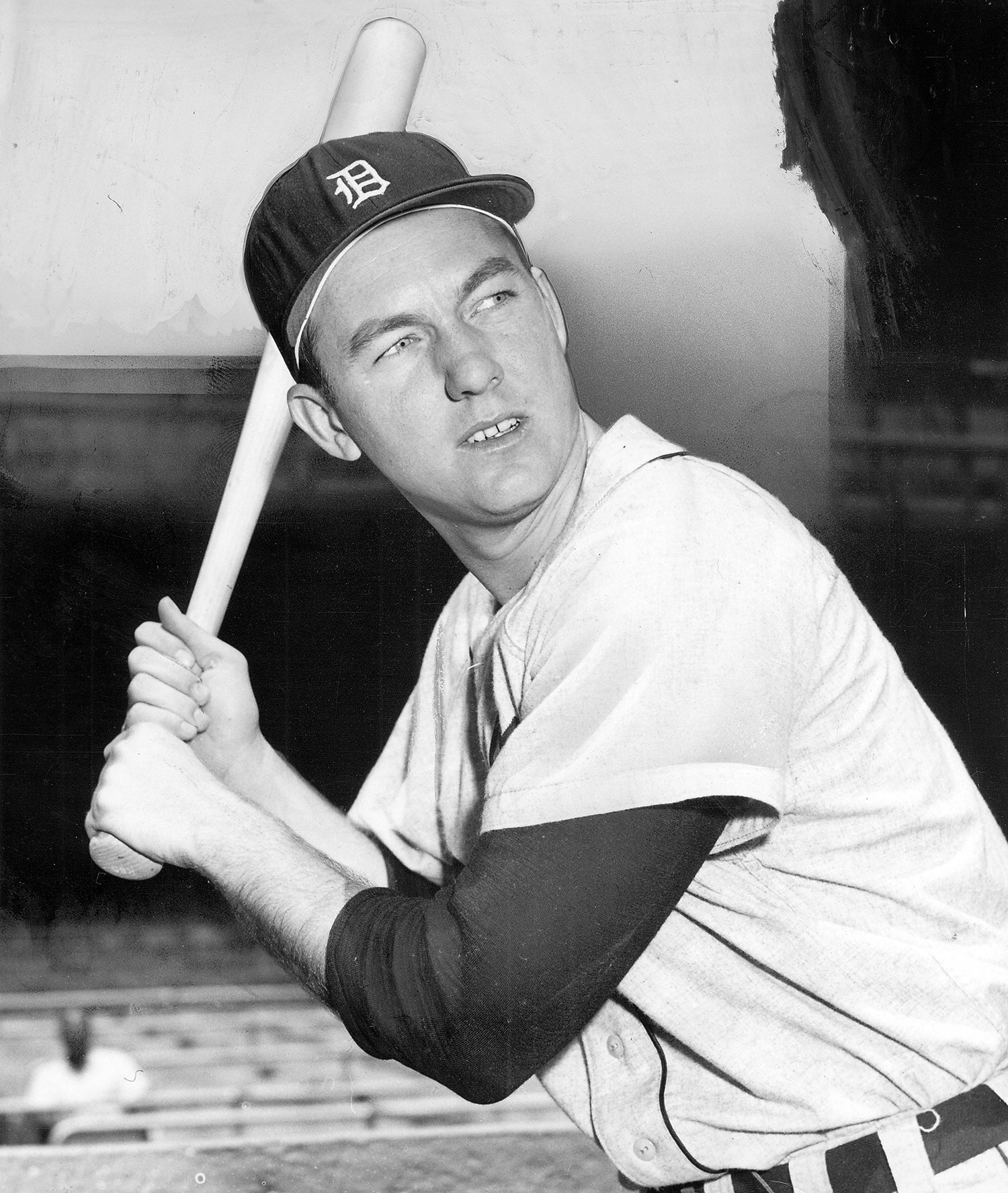

“I really didn’t know what was happening until after I got to the hotel,” Ashby told the AP. “I went into a restaurant to get something to eat and in walked Al Kaline. I’m not a hero worshiper or anything, but just the thought of seeing Kaline made me nervous. It hit me right there – the realization of being in the major leagues.”

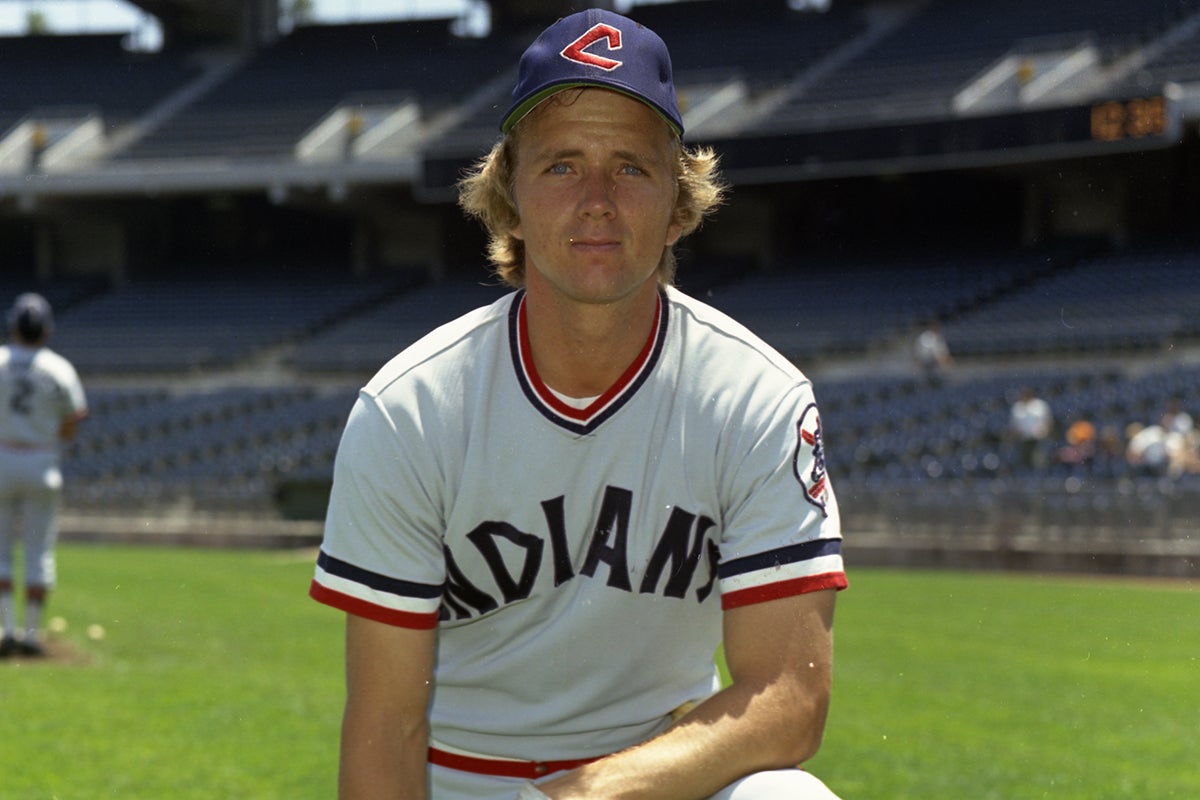

Ashby shuttled between Cleveland and the minors for the rest of the season, batting .172 in 11 games with the Indians. But he impressed manager Ken Aspromonte with his workmanlike approach to the game.

“He’s a hell of a ballplayer,” Aspromonte told the AP. “He caught on right away to the type of game I wanted him to call.”

Ashby spent much of the 1974 season in Triple-A, batting .284 with a .385 on-base percentage for Oklahoma City. He appeared in 10 games for Cleveland that year as Dave Duncan caught nearly every day.

But Cleveland sent Duncan to the Orioles on Feb. 25, 1975, in a deal for Boog Powell, leaving John Ellis to handle the catching duties for new manager Frank Robinson. Robinson and Ellis, however, clashed throughout the season until Robinson announced in July that Ellis would no longer be the team’s regular catcher.

Ashby, who started the year in Triple-A, returned to Cleveland in late April and saw more and more playing time as the year went on, finishing with a .224 batting average in 90 games.

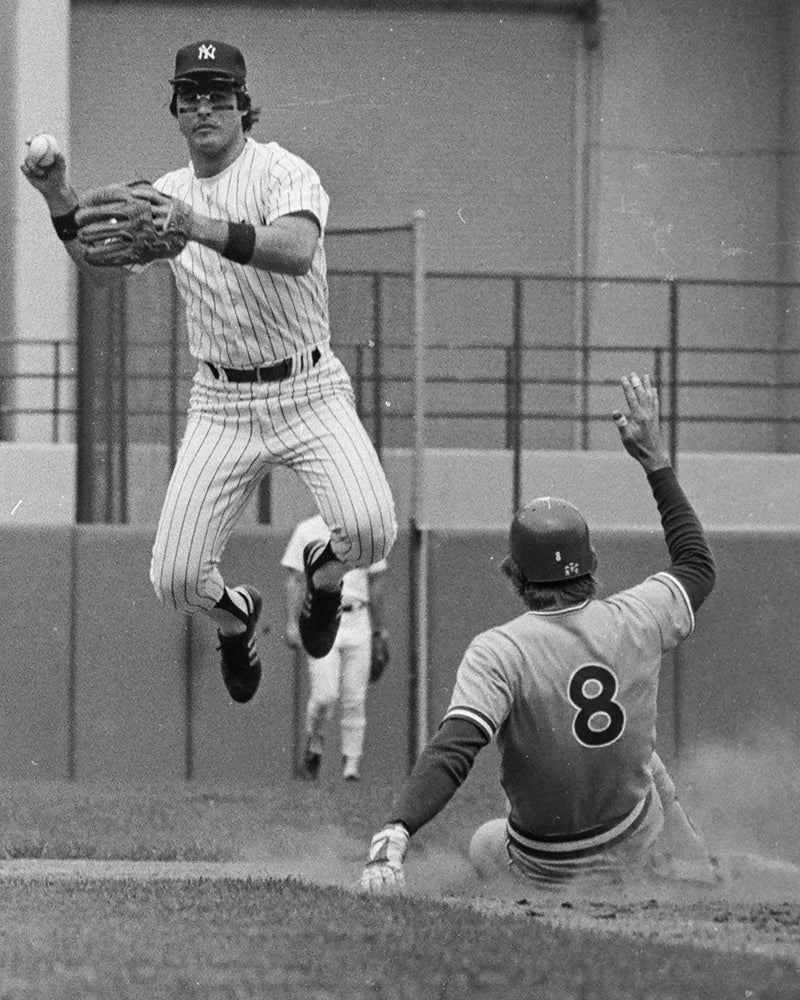

In 1976, Ashby got the Opening Day start for Cleveland behind the plate and was named the winner of the Gordon Cobbledick Golden Tomahawk Award, presented by the team’s Baseball Writers’ Association of America chapter to the club’s most underrated player.

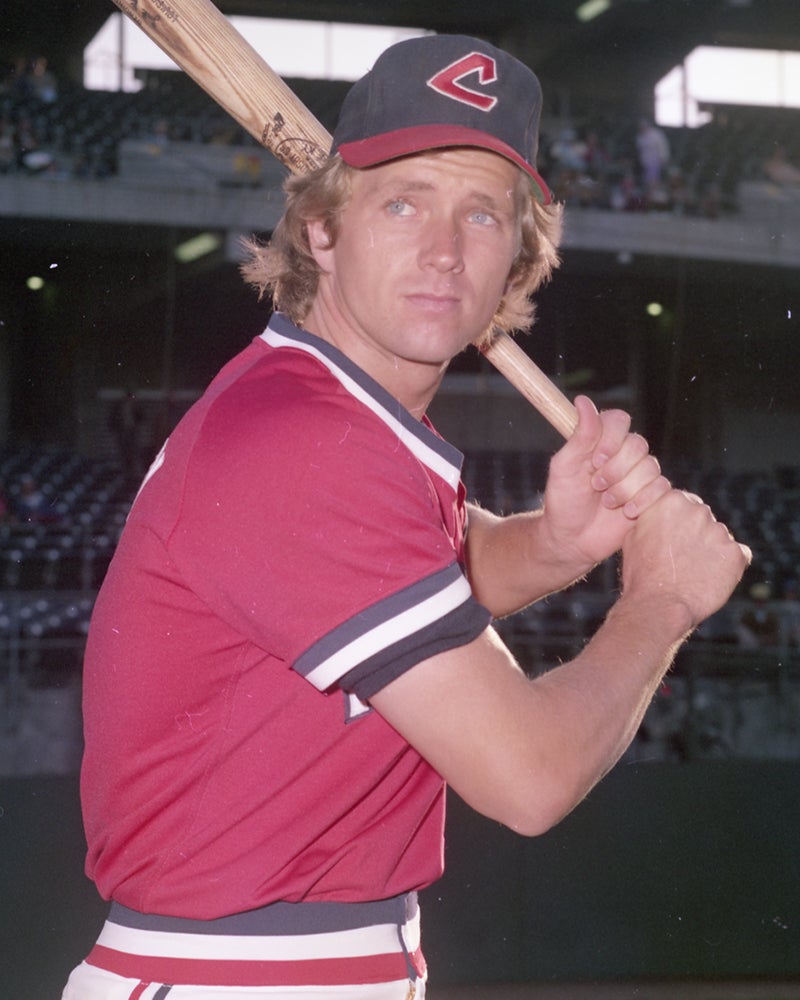

Ashby and veteran Ray Fosse split the catching duties for the Indians that year, with Ashby hitting .239 in 89 games while missing time with a broken thumb. But with Fosse seemingly in his prime and prospect Rick Cerone on the way, the Indians felt they could trade from their catching depth.

On Nov. 5, Cleveland sent Ashby and first baseman Doug Howard to the Blue Jays in exchange for pitcher Al Fitzmorris, who had won 15 games for the Royals in 1976 before being selected in the expansion draft by Toronto.

Ironically, a month later the Indians traded Cerone to the Blue Jays in a deal for Rico Carty, who Toronto had selected off Cleveland’s roster in the expansion draft.

“I’m shocked at the trade,” Ashby told the Cleveland Press. “I hate to leave because I grew up in the organization and because the Indians are going to be winners soon.

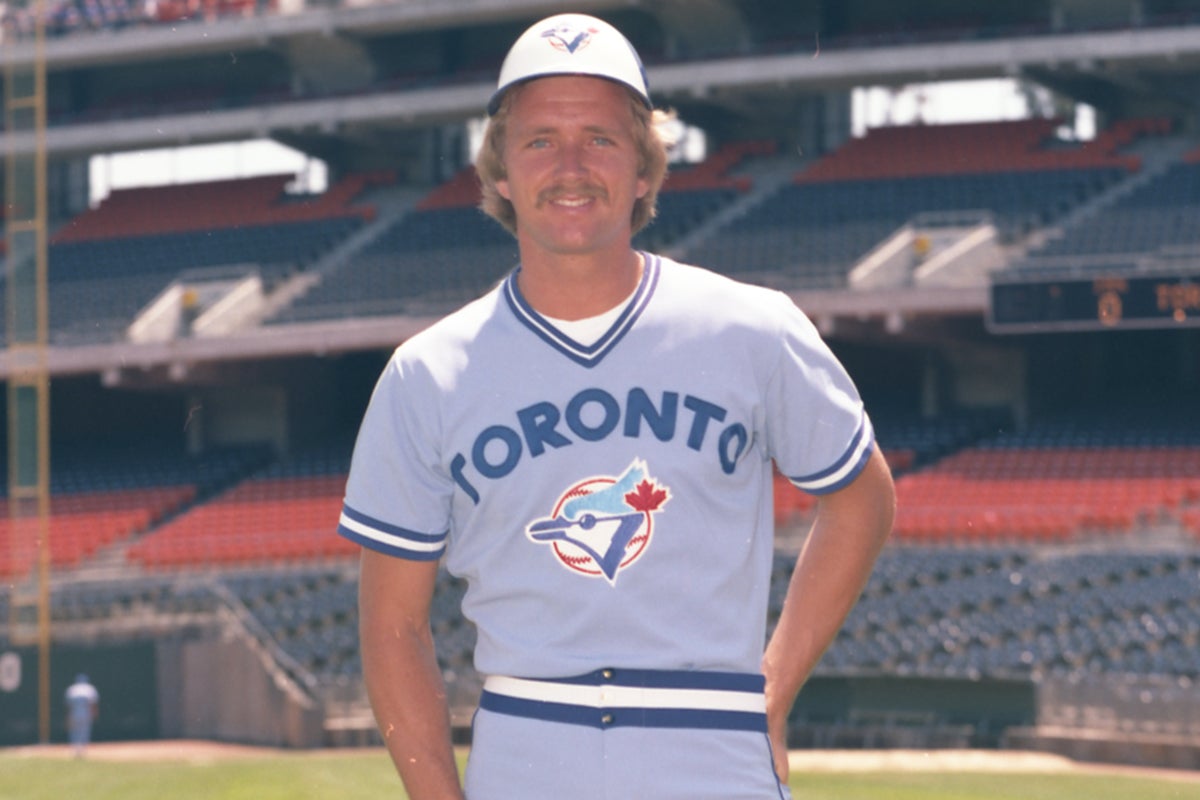

“I hope the (Blue Jays) got me to be the catcher. Maybe it will be a break.”

But with Cerone coming to Toronto, the Blue Jays felt they had a young catching duo as good as anyone’s in the big leagues. Rumors circulated that Ashby would be traded to the Angels, but Cerone started on Opening Day 1977 in the Blue Jays’ first-ever game, and Ashby started Game 2. Cerone, however, broke his right thumb during the second week of the season and was sent to Triple-A when he was healthy again.

Ashby, meanwhile, played in 124 games that year, hitting .210 with two home runs, 29 RBI and 50 walks while throwing out 48 percent of potential base stealers. He and Cerone platooned throughout the 1978 season, with Ashby getting the starts against right-handers and hitting .261 with nine homers and 29 RBI in 81 games.

“I hit the ball well at the start of the ’76 season in Cleveland,” Ashby told the Toronto Star during the summer of 1978. “But I have never hit it as hard as I have lately.”

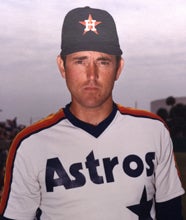

But with Cerone thought to be a budding All-Star, the Blue Jays decided – as the Indians had – to trade from a position of strength. On Nov. 27, 1978, Toronto shipped Ashby to the Astros in exchange for outfielder Joe Cannon, infielder Pete Hernández and pitcher Mark Lemongello.

“I’m not sure how I feel about the trade,” Ashby told the Canadian Press. “I’m still trying to get used to the idea.”

He didn’t know it at the time, but Ashby had found a place to call home for most of the rest of his days in baseball.

The Astros had an open spot at catcher after trading Joe Ferguson to the Dodgers midway through the 1978 campaign. Bruce Bochy and Luis Pujols had handled the catching duties the rest of that season, but Ashby was the Astros Opening Day starter in 1979 – the third different team with which Ashby started on Opening Day in the last four seasons.

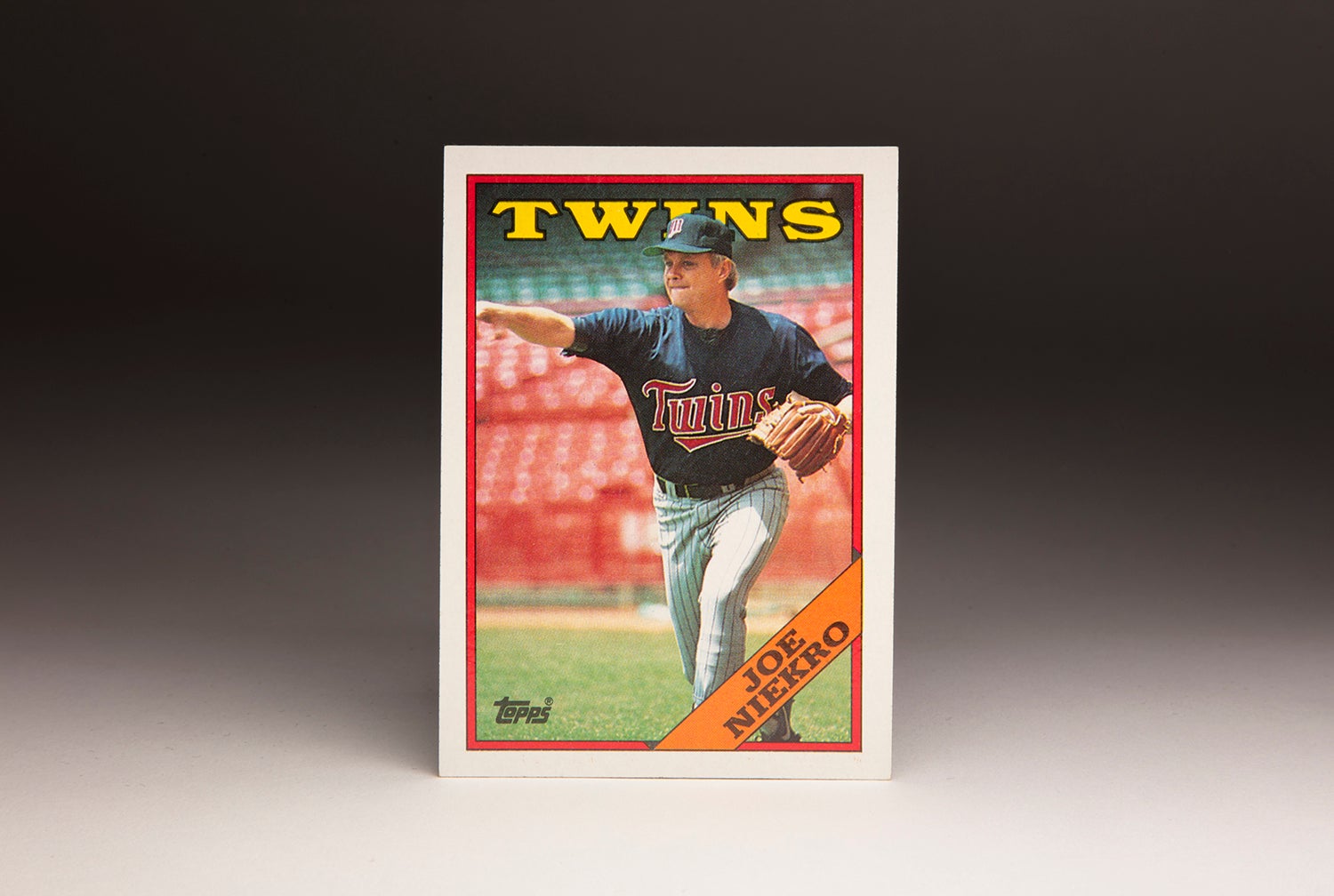

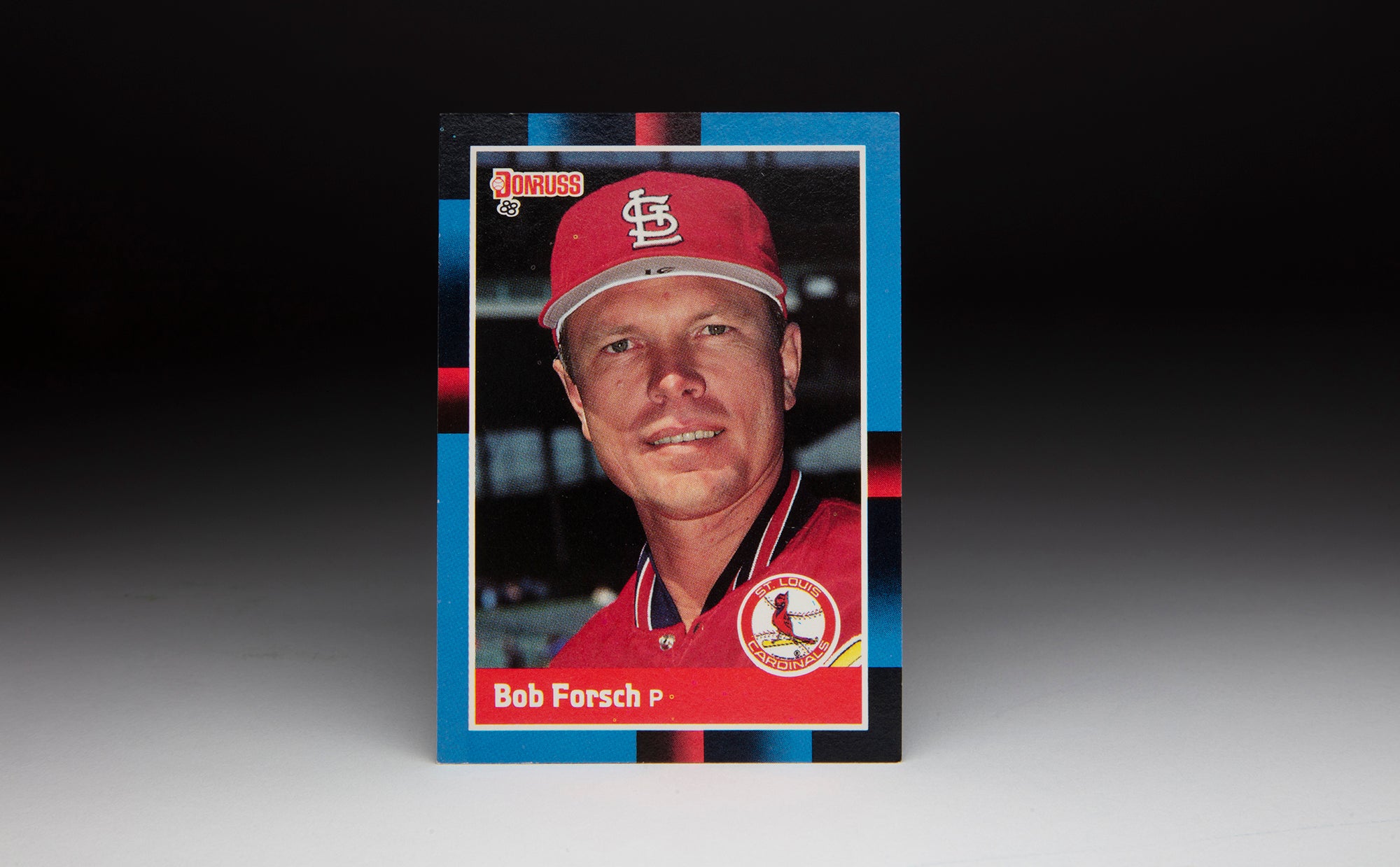

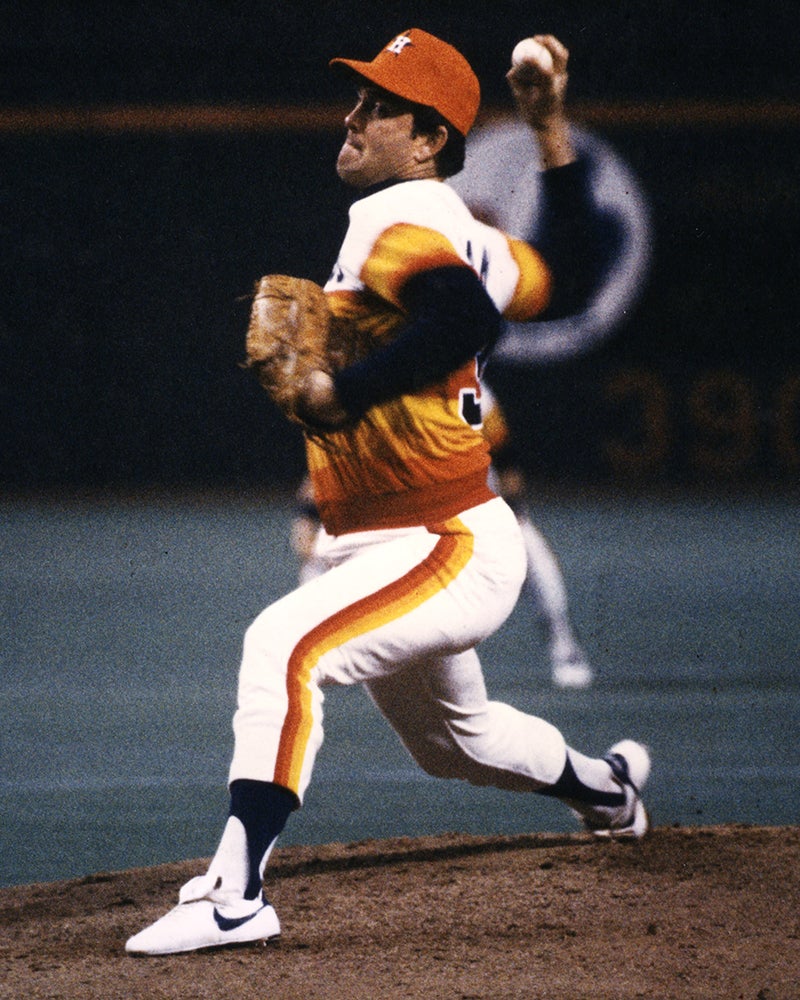

He was now catching flamethrower J.R. Richard and knuckleballer Joe Niekro in the same rotation, a challenge that often resulted in nagging hand injuries. Meanwhile, Ken Forsch – another member of the Astros’ rotation – tossed a no-hitter against the Braves on April 7, 1979, with Ashby calling the gem while recording two hits and three RBI.

At the time, it was the earliest no-hitter by calendar date in MLB history.

“We never gave ’em a fastball to hit after the fourth inning,” Ashby told the AP, calling it “the most thrilling moment I’ve ever had in my career.”

Ashby needed time to adjust to NL pitching, however, and batted just .202 over 108 games that year. The Astros, however, battled Cincinnati for the NL West title for much of the season before falling a game-and-a-half short.

Sensing one big move might put his team over the top, Astros owner John McMullen signed free agent Nolan Ryan to a four-year deal worth $4.5 million.

Now, Ashby was charged with catching two of the best fastballs in the game (Ryan and Richard), a baffling knuckleball (Niekro) and a biting left-handed slider (from reliever Joe Sambito). He was also catching what might have been the best pitching staff in the game.

Houston led the NL West for much of the 1980 season – despite Richard missing the second half after suffering a stroke – before being swept by the Dodgers in the final three games of the year, necessitating a one-game playoff when both teams finished at 92-70. But Houston won that game 7-1 at Dodger Stadium behind a complete game from Niekro, who allowed only one unearned run.

Ashby had a hit and a walk in the victory, finishing the season with a .256 batting average, three home runs and 48 RBI in 116 games.

Houston manager Bill Virdon started the right-handed hitting Pujols against Phillies lefty Steve Carlton in Game 1 of the NLCS, and Ashby made his postseason debut in Game 2, going 0-for-5. Pujols then started the next three games – but Ashby entered the deciding Game 5 as a pinch-hitter in the bottom of the sixth, singling off Marty Bystrom to score Denny Walling and tie the game at 2.

The Astros then scored three times in the bottom of the seventh to take a 5-2 lead – which seemed more than enough with Ryan on the mound. But Philadelphia scored five times in the eighth before Houston tied the game at 7 in the bottom of the eighth.

Finally, Garry Maddox’s double in the top of the 10th scored Del Unser with the go-ahead run, and Dick Ruthven retired the Astros in order in the bottom of the 10th to give Philadelphia an 8-7 victory and send the Phillies to the World Series.

“This is one of the greatest ballgames I have ever played in,” Ashby told the AP, “and this was one of the greatest series anybody has ever seen. We should have won it, but that’s baseball.”

The Astros returned to the postseason in 1981 after acquiring Don Sutton and Bob Knepper to bolster their pitching staff. But it was Ryan who put the exclamation point on their season when he tossed his fifth career no-hitter on Sept. 26 vs. the Giants.

Ashby was behind the plate for the record-setting game – a gem that broke the record for career no-hitters that Ryan had shared with Ashby’s boyhood hero, Sandy Koufax.

“Early in the game, I didn’t think he had his very best fastball but he had a good curve and that helped him get ahead of the hitters,” Ashby told United Press International. “Then toward the end, he got so pumped up he got his fastball.”

Ashby returned to his 1978 form at the plate, hitting .271 with four homers, 33 RBI and 35 walks in 83 games in that strike-shortened season. Houston faced the Dodgers in the Division Series, and Ashby’s walk-off, two-run home run in Game 1 off Dave Stewart gave the Astros a 3-1 win.

“It’s a dream come true,” Ashby told UPI. “Even though I’m not a big home run hitter, I knew as soon as I caught flight of the ball that it was going to be gone. I started jumping for joy even before the fans knew it, I think.”

But Ashby played in just two of the last four games of the series – going hitless in six at-bats – as Los Angeles won to advance to the NLCS.

Ashby had his best season at the plate in 1982, batting .257 with 12 homers and 49 RBI in 100 games. His timing was optimal as he was due to become a free agent – but Ashby returned to the Astros on a three-year deal (with an option for 1986) that would eventually be worth $1.7 million.

The Astros reversed their 77-85 record in 1982 to 85-77 in 1983, but Ashby slumped all season. A bout with the flu sidelined him in Spring Training and home-plate collisions – followed by dizzy spells – limited him to a .229 batting average over 87 games. He also threw out only 25 percent of the runners who attempted to steal.

“He’s improved,” Astros manager Bob Lillis told the AP about Ashby’s offseason work in the spring of 1984. “But he needs to improve more.”

Ashby did improve, batting .262 over 66 games while ceding playing time to young Mark Bailey. In 1985, Ashby again served as Bailey’s backup, hitting .280 with eight homers and 25 RBI in 65 games.

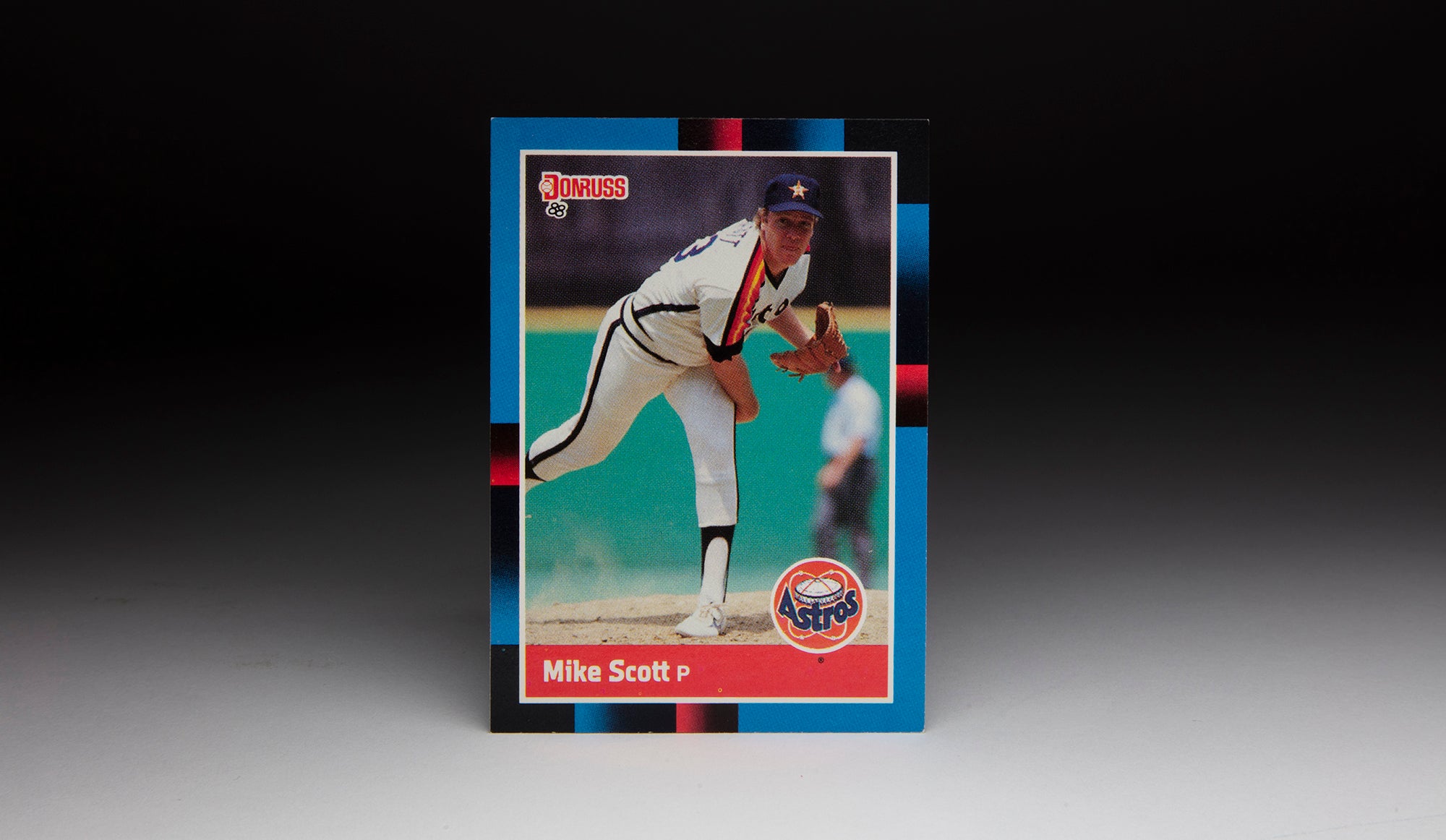

Then in 1986, Hal Lanier replaced Lillis as the team’s manager. He inherited a 31-year-old starting pitcher named Mike Scott who had won 18 games in 1985 but had struck out just 137 batters over 221.2 innings and had a spotty track record before that.

But armed with a split-fingered fastball that he worked on in 1985, Scott became an ace. Meanwhile, Bailey was hitting .176 when he was optioned to Triple-A Tucson in June. John Mizerock was recalled to take his place, but it was Ashby who received the bulk of the playing time the rest of the season – and he hit .257 over 120 games, his most appearances since 1977.

Ashby was behind the plate on Sept. 25 when Scott no-hit the Giants at the Astrodome to clinch the National League West title for Houston. The night before, Ashby was the catcher when Ryan one-hit the Giants over eight innings, striking out 12 batters – one fewer than Scott totaled the next day.

Ashby said that going into Scott’s start, he couldn’t imagine a better start than Ryan’s.

“But (Scott) matched it,” Ashby told the AP about the third no-hitter of his catching career.

In the NLCS vs. the Mets, Ashby played every inning of every game as the Astros once again provided fans with one of the most competitive LCS in baseball history. His two-run home run in the second inning of Game 4 – he got a second chance in that at-bat when his foul popup fell to the ground – gave Scott all the runs he would need in a 3-1 Houston win that tied the series.

In Game 5, Ashby scored the game’s first run in the fifth inning after doubling off Dwight Gooden and scoring on a Bill Doran groundout. But the Mets tied the game in the bottom of the fifth on a Darryl Strawberry home run off Ryan, and New York won the game in the bottom of the 12th on a Gary Carter single.

Then in Game 6 – needing a win to force Game 7 and give Scott another start – Houston was leading 3-0 heading to the top of the ninth when New York rallied to tie the game. After both teams scored a run in the 14th, the Mets scored three times in the 16th before the Astros rallied for two runs. But with two on and two out, Jesse Orosco fanned Kevin Bass to end the game and Houston’s season.

Ashby caught all 16 innings of that epic game.

A free agent following the season, Ashby – like many players – found few offers that winter and returned to the Astros on a two-year deal. He proceeded to have his best season at the plate, hitting .288 with 14 homers and 63 RBI. He also had a front-row seat for one of Ryan’s best years – one where he went 8-16 but struck out 270 batters and posted an NL-best 2.76 ERA in his age-40 season.

“I’ve never seen him stronger or better,” Ashby said after Ryan struck out 16 Giants batters on Sept. 9 in a game where Ashby was the Astros’ cleanup hitter. “In eight years, I’ve never seen him better.”

But the Astros finished in third place with a 76-86 record as Ashby played little during the final three weeks due to a broken finger.

In 1988, a back injury put Ashby on the disabled list for two months – and brought future Hall of Famer Craig Biggio to the majors for the first time to replace him. Ashby finished the year batting .238 in 73 games and was one of 12 players ruled to be “new-look” free agents after the season following a collusion ruling by an arbitrator. But he returned to the Astros on a one-year deal worth $550,000.

Ashby was hitting .164 through 22 games in 1989 when the Astros agreed to trade him to the Pirates for outfielder Glenn Wilson. But as a 10-and-5 player, Ashby had veto rights – and told the Astros he would only accept the trade if they added $450,000 to his salary.

The Astros balked, and three days later, general manager Bill Wood called Ashby off a team bus and told him he was being released.

“I was devastated,” Ashby told Knight-Ridder Newspapers. “I was put in a position that I didn’t want my wife and six children in – to change everyone’s lifestyle and move around the country for the purpose of me playing baseball.”

Ashby never played in another big league game. But he didn’t stay away from baseball for very long.

Ashby began working in TV in the early 1990s before managing the Rio Grande Valley WhiteWings of the independent Texas-Louisiana League in 1994 and 1995. He then managed the Astros’ Class A team in Kissimmee, Fla., in 1996.

Ashby made it back to the majors in 1997 as the Astros’ bullpen coach under Larry Dierker but decided to return to broadcasting. He signed on as the team’s radio color analyst in 1998 and stayed in that position through 2006 before joining the Blue Jays broadcast team for six seasons. He then returned to Houston for the final four seasons of his 19-year broadcast career.

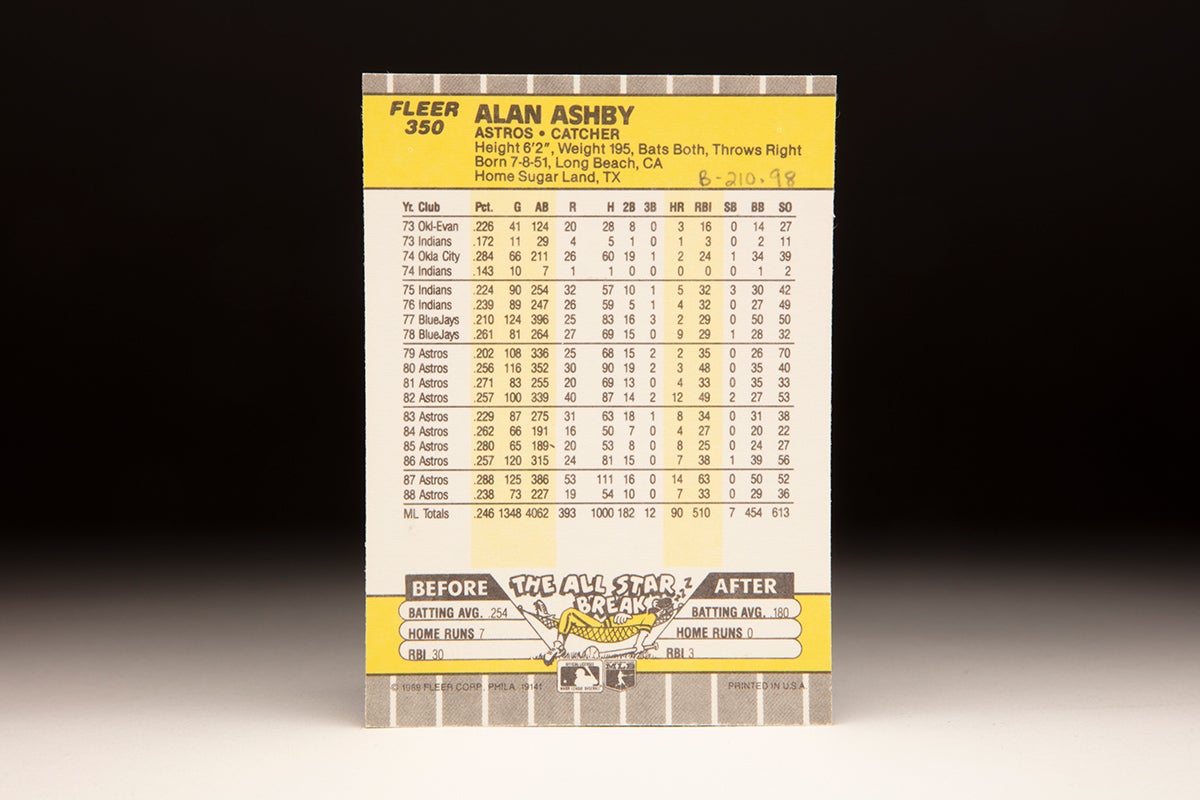

Over 17 seasons as a player, Ashby hit .245 in 1,370 games with 1,010 hits, 90 home runs and 513 RBI. Among switch-hitting catchers, only six have appeared in more big league games.

It is a record of longevity due in part to his ability to improve as a hitter throughout his career.

“I’ve just become a better hitter,” Ashby told the AP in the spring of 1988, “and I don’t know why it happened later in my career. But it did.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum