- Home

- Our Stories

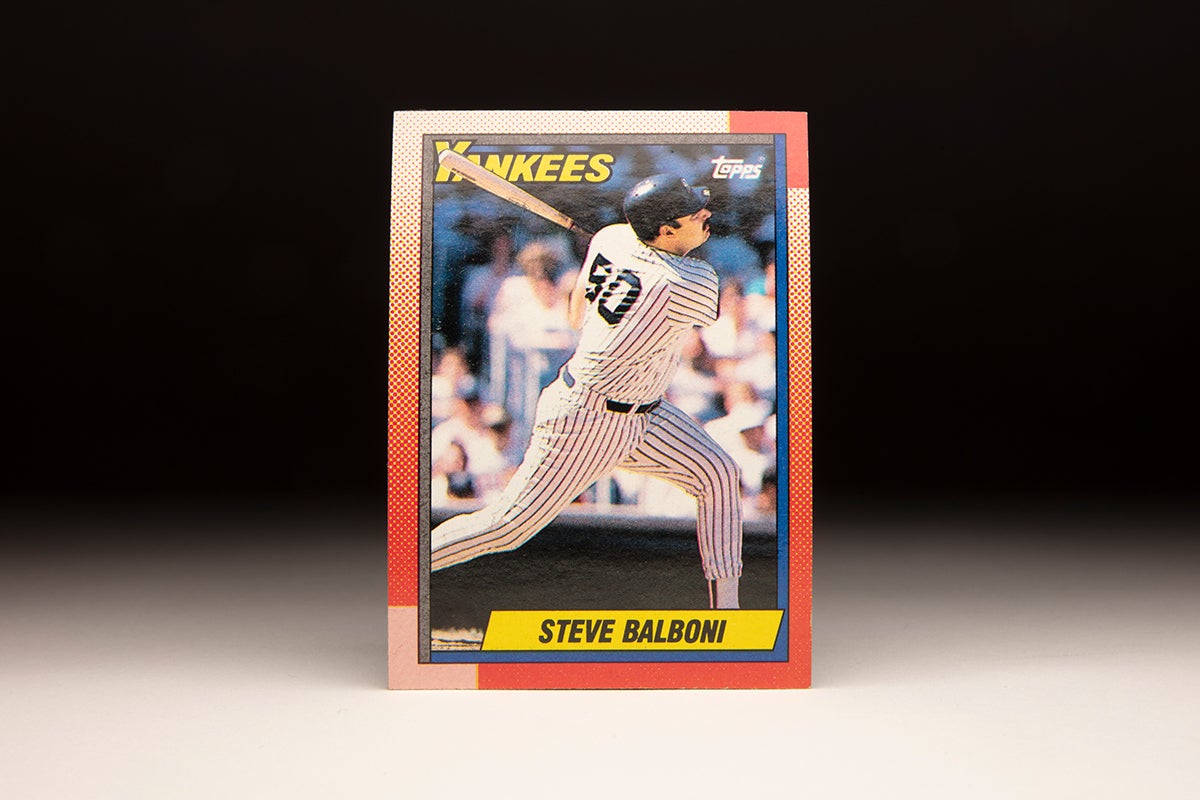

- #CardCorner: 1990 Topps Steve Balboni

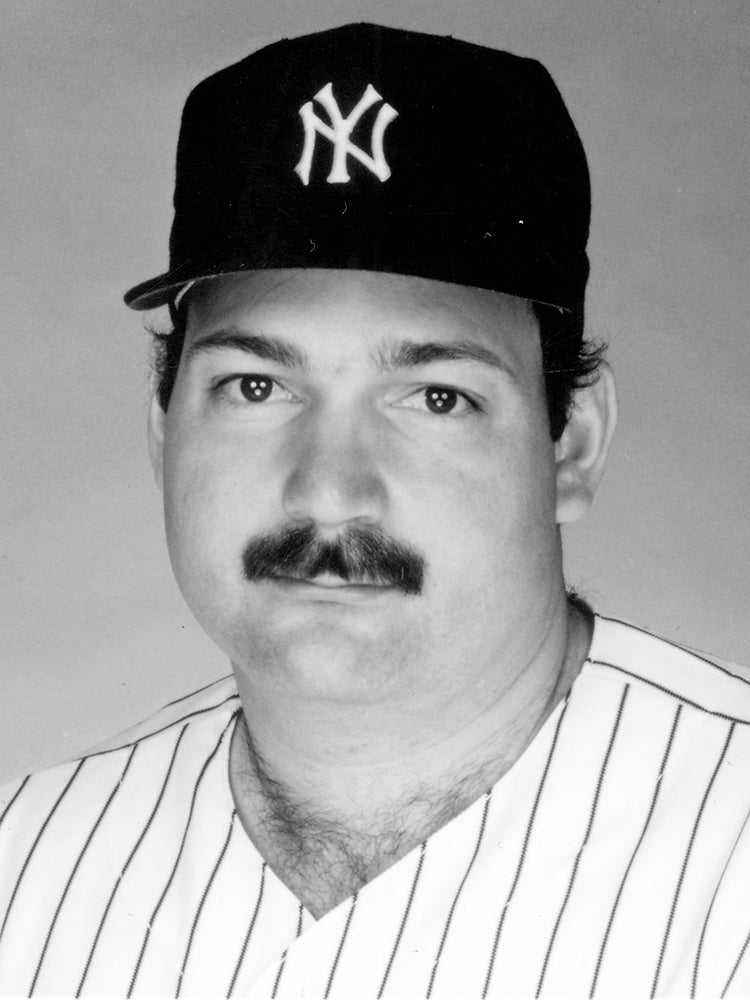

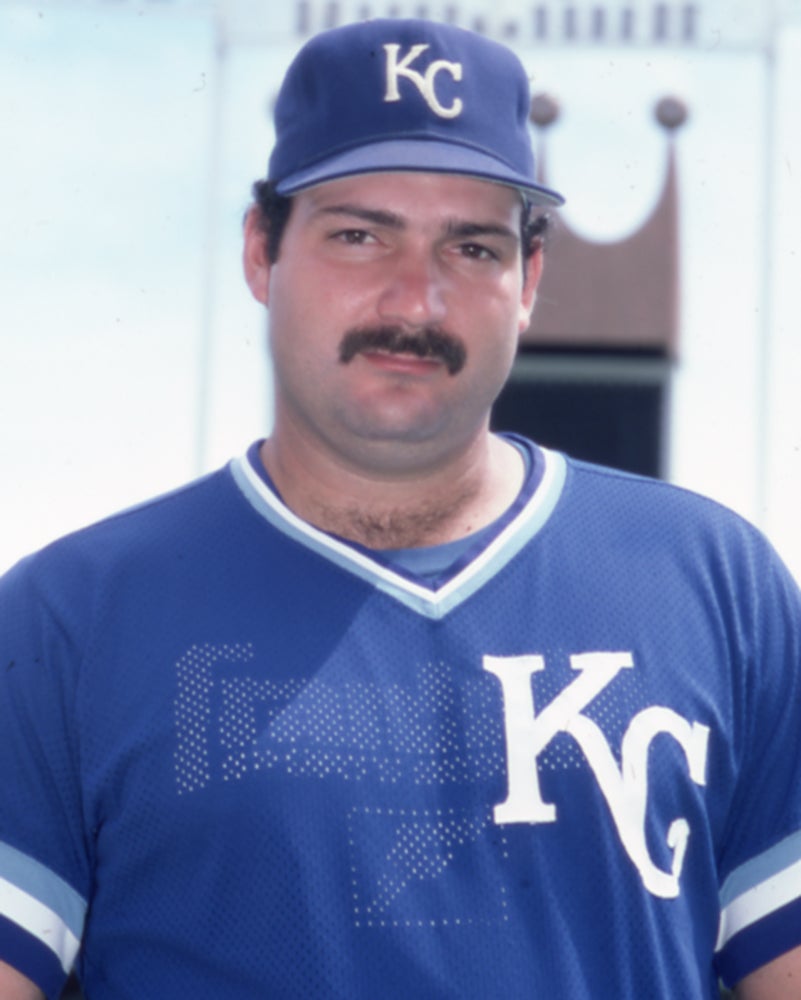

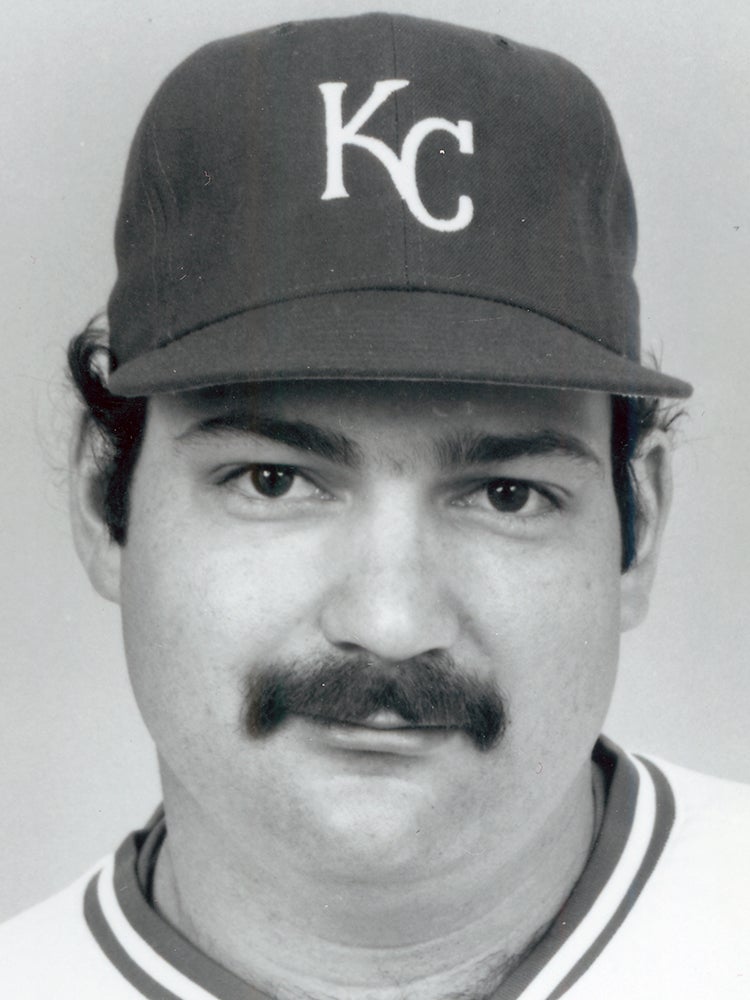

#CardCorner: 1990 Topps Steve Balboni

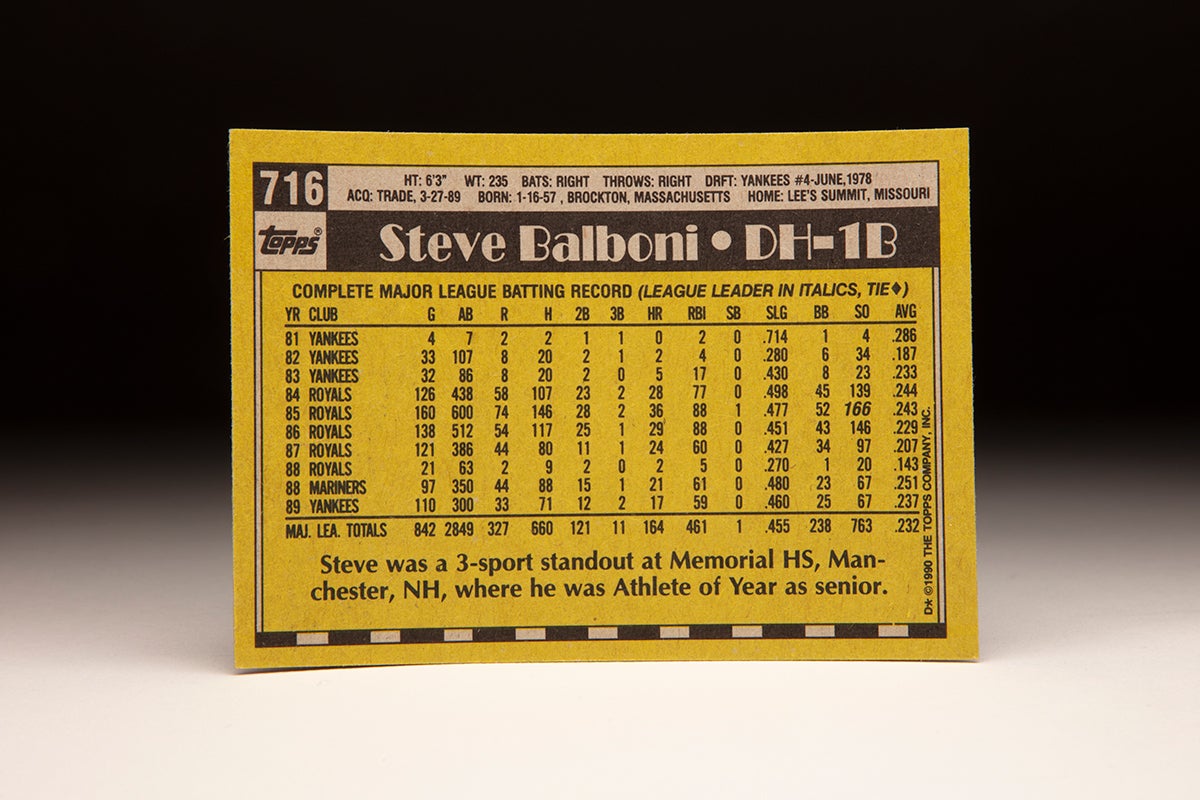

When Steve Balboni struck out 166 times in 1985, only three American League players had ever fanned more often in any season.

In an era where strikeouts were considered failures, Balboni was often dismissed as one-dimensional. But in today’s analysis, virtually every club would take Balboni’s strikeouts in exchange for the 36 home runs he hit that year while helping the Royals win the World Series.

Born Jan. 16, 1957, in Brockton, Mass., Balboni played baseball, basketball and football at Memorial High School in Manchester, N.H., and hit better than .500 as a senior. But he was not selected in the 1975 MLB Draft and instead enrolled at Eckerd College in St. Petersburg, Fla.

“They were the only ones who called,” Balboni told the Boston Globe in 1987. “I went to look at the campus and I really liked the way the program was set up because I could go and play right away.

“I always knew I wanted to play baseball as a career.”

Eckerd recruited several New Hampshire players in the mid-1970s, including future San Francisco Giants general manager Brian Sabean. The college did not offer scholarships and had a hard time attracting local players, so coaches turned north to find athletes who were looking for a chance to play in the sunshine.

Joe Lefebvre, who played in the big leagues for six years as an outfielder with the Yankees, Padres and Phillies, was a pitcher/center fielder for Eckerd a year ahead of Balboni.

“Steve is doing what everybody expected of him: Hitting home runs,” Lefebvre told the Concord (N.H.) Monitor in 1976 when Balboni was a freshman. “He leads the team in homers and is batting in the .400s.”

As a sophomore in 1977, Balboni emerged onto scouts’ radar when he hit 26 home runs – an NCAA record at any division – while driving in 77 runs. In 1978, he hit .403 and was named to the Sporting News All-America team – the only Division II player selected.

At Eckerd, he acquired his nickname “Bye-Bye” Balboni.

“The nickname can work both ways,” Balboni told the Valley News of West Lebanon, N.H., adding that he didn’t particularly like it. “It goes as good with a strikeout as a home run. I just don’t like to be singled out.”

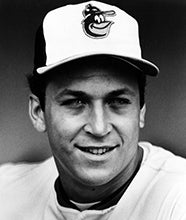

The Yankees selected Balboni in the second round of the 1978 MLB Draft – four picks after the Orioles took Cal Ripken Jr. – on the recommendation of scout Bill Livesey, who had coached Balboni at Eckerd College for two seasons. The Yankees sent Balboni to Fort Lauderdale of the Class A Florida State League, where he hit .205 with one home run in 60 games. The Yankees sent him to the Florida Instructional League after the season, and Balboni returned to Fort Lauderdale in 1979, where he hit .252 with 26 homers and 91 RBI in 140 games.

“Instructional League was a big help,” Balboni told the Valley News. “It meant 45 more games, and there were a lot of coaches and time to work in the batting cage.”

The work paid off in 1980. Assigned to Double-A Nashville of the Southern League, Balboni became a national phenomenon with a torrid start to the season. He was featured in the June 9 issue of Sports Illustrated while he was on pace for more than 60 homers and 170 RBI.

“If I keep my average above .300 and hit a few more homers and my RBIs keep going up, I’ll be happy,” Balboni told the Valley News. “The main thing has been more consistent contact.”

Balboni finished the season with 34 home runs, 122 RBI and a .301 batting average in 141 games. He also struck out 162 times – but was still the unanimous winner of the league’s Most Valuable Player Award, which gave him two MVPs in a row following his Florida State League honors in 1979.

“Any time you have a young hitter with that kind of power, he’s going to strike out a lot,” Bill Bergesch, the Yankees’ vice president of baseball operations, told the Newark Star-Ledger in the spring of 1981 when Balboni was in major league camp. “He’s improving, though, and if he can keep the strikeouts under control, he could become an awesome hitter in the majors.”

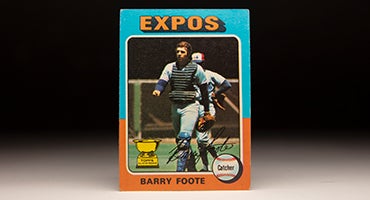

The Yankees sent Balboni to Triple-A Columbus to start the season but recalled him on April 21. The next night, he was in the starting lineup at Yankee Stadium and went 1-for-2 with a triple, an RBI walk and two runs scored. He appeared in his next game on April 27 vs. the Tigers – notching an RBI double in three at-bats – before he was returned to Triple-A on April 28 when the Yankees needed to make room in the lineup for newly acquired catcher Barry Foote.

Balboni came back to New York in September, finishing the Triple-A season with 33 homers and 98 RBI – the top totals in the International League – and a .247 batting average to go along with 146 strikeouts. He played in four total games with the Yankees in 1981 but was not included on their postseason roster.

The Yankees lost the World Series to the Dodgers that fall, and in the offseason owner George Steinbrenner retooled the team with a speed-first lineup. Balboni came to Spring Training with the Yankees in 1982 but saw little action.

“I’m not giving up. No way am I giving up,” Balboni told the Fort Lauderdale News. “I can still play this game. I’m good enough. All I need is a chance to prove it.”

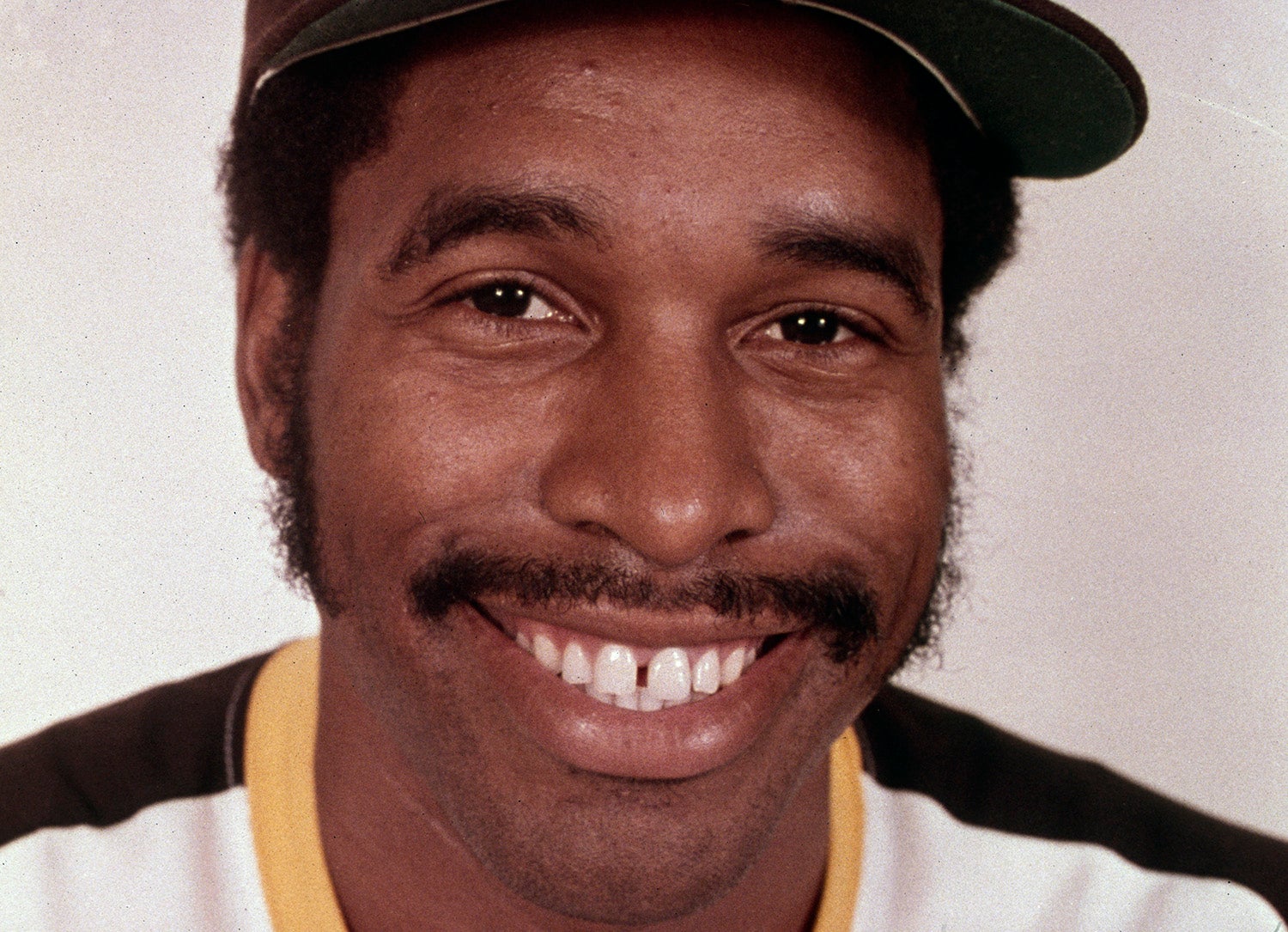

The Yankees sent Balboni back to Columbus to start the 1982 campaign before recalling him on May 5. Eight days later, he hit his first big league home run against Oakland’s Tom Underwood in a 6-4 Yankees victory.

“It’s all confidence,” Yankees hitting coach Mickey Vernon told Newsday. “We always thought Steve had the potential, we just felt that he just had to keep working at it. But let’s not go overboard yet. He’s got a long way to go. The potential is there for a long career, but let’s not put any pressure on him yet.”

But in New York, pressure comes with the job. The Yankees moved Balboni back and forth from the minors throughout the season, and he was sidelined by stomach issues late in the year. He finished the season with 32 homers and 86 RBI in just 83 games with Columbus while batting .284. But with the Yankees, he hit just .187 with two homers and four RBI in 33 games.

In 1983 – with Don Mattingly about to pass him on the organizational depth chart – Balboni hurt his shoulder in Spring Training. He was sent back to Columbus on March 20.

“I don’t know what’s going to happen. I don’t want to spend another year in Columbus,” an emotional Balboni told Gannett News Service. “If they don’t need me, why can’t they send me to somebody who does need me? I know I would have gotten a shot if I didn’t get hurt, and now I have to stay in Columbus because I got hurt in Spring Training.

“All I want is experience and a chance to hit major league pitching. How else will I ever find out what’s going to happen to me?”

Balboni’s numbers in 1983 were remarkably similar to those he put up in 1982. He hit .274 with 27 home runs and 81 RBI in 84 games for Columbus while batting .233 with five homers and 17 RBI in 32 games for the Yankees.

On Dec. 8, 1983 – with Balboni finally out of minor league options – the Yankees traded him and pitcher Roger Erickson to the Royals for pitcher Mike Armstrong and a minor leaguer.

“I’m happy,” Balboni told Newsday after the trade. “I feel good about Kansas City. It was getting so disappointing: Up, down, up, down. When I started, the Yankees (organization) was a great place to be. But…I realized I’d be better off somewhere else.”

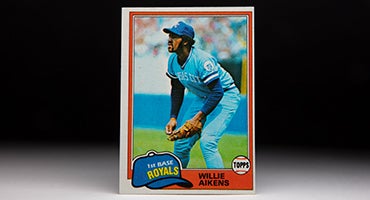

The Royals were looking for a replacement for first baseman Willie Aikens, who was facing a long suspension in 1984 following federal drug charges. Balboni would be given every chance to win that job.

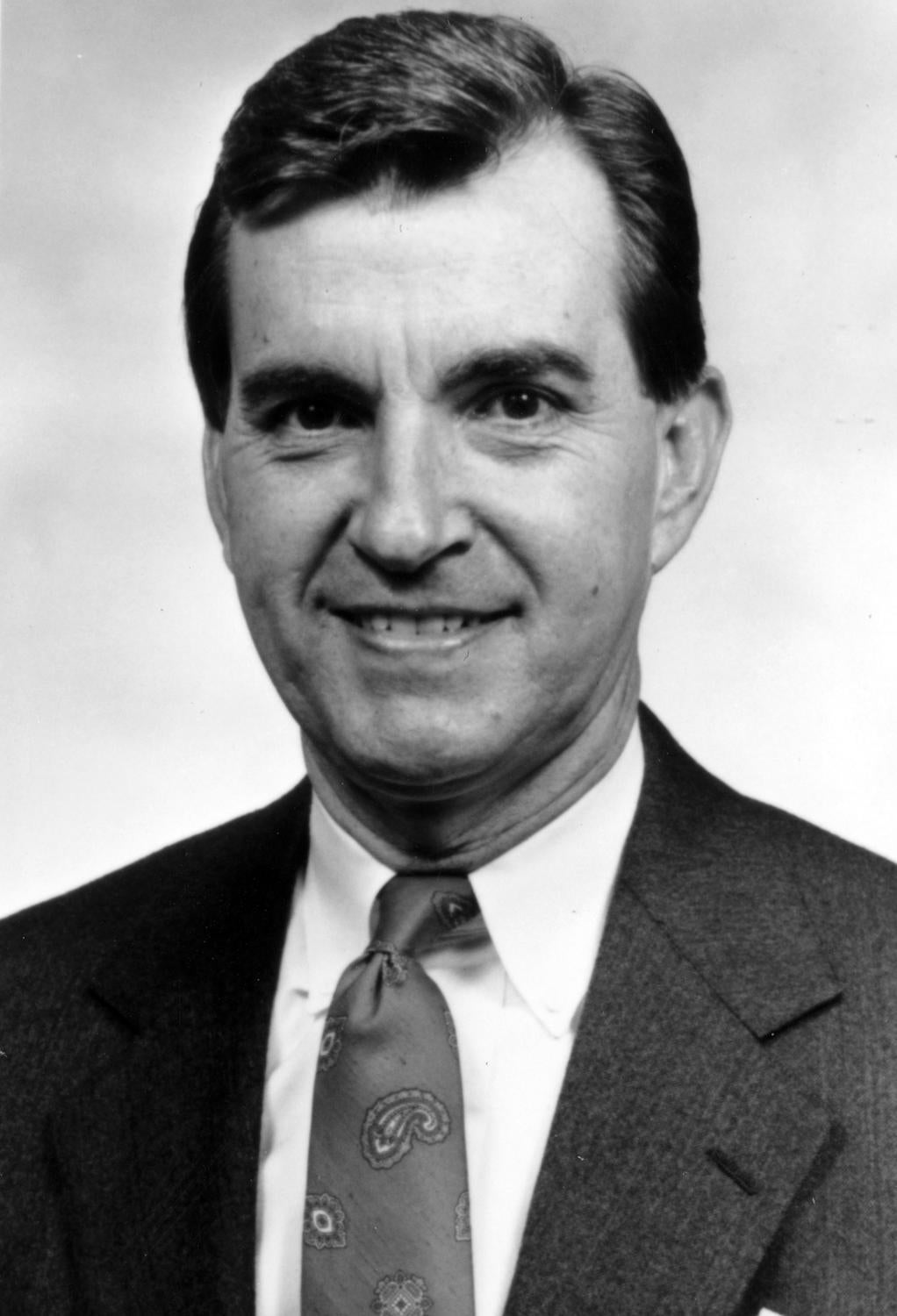

“(Balboni) has a chance,” Royals manager Dick Howser told Newsday, “to put some awesome numbers on the board.”

Balboni started at first base on Opening Day in 1984 and played in 126 games, batting .244 with 28 home runs and 77 RBI – totals that led all Royals’ batters. He also fanned 139 times, including striking out in nine straight at-bats over three games in late August to threaten Dean Chance’s AL record of 11 straight strikeouts set in 1966.

But Balboni regrouped in September to hit .329 with seven homers and 20 RBI to help Kansas City win the American League West title, giving Balboni his first chance to play in the postseason. But he went 1-for-11 with only a single as Detroit swept the Royals in three games.

Howser, however remained committed to Balboni in 1985.

“If he can get 600 at-bats, he’s got a chance to contend for the home run title,” Howser told the Cleveland Plain Dealer in Spring Training of 1985. “He’s a very tense player. I just put him in the lineup last year and never said much to him at all.

“He’ll never be a relaxed player. It’s just not in his makeup.”

But Balboni remained a productive player, fulfilling his potential in 1985 by hitting 36 homers – a new Royals record – and driving in 88 runs. He played in 160 games, got exactly the 600 at-bats Howser wanted and finished seventh in the AL with 66 extra base hits. He placed 19th in the AL Most Valuable Player Award voting for the second straight year – which was also the second year in a row the Royals won the AL West title.

Balboni’s two-run homer in Seattle on Sept. 26 was his 35th of the year, surpassing the 34 hit by Kansas City’s John Mayberry in 1975. More importantly, the homer helped the Royals win 5-2 and move into a first-place tie with the Angels in the AL West. The Royals finally passed the Angels on Oct. 3 in a 4-1 victory over California where Balboni hit his 36th home run.

The Royals clinched the division on Oct. 5 by rallying from a 4-0 deficit to beat Oakland 5-4 in 10 innings. Balboni’s seventh-inning single off Jay Howell scored George Brett with the game-tying run.

In the postseason, Howser employed an unusual lineup strategy with Balboni, batting him sixth or seventh despite Balboni having 14 more home runs during the season than any teammate other than Brett. Balboni hit just .120 (3-for-25) with one RBI and no extra base hits against Toronto in the ALCS – but the one RBI was a key one. In Game 3, with the Blue Jays ahead 2-games-to-none in the series, Balboni blooped a single to center field in the bottom of the eighth off Jim Clancy to score Brett – who would be named the ALCS MVP – with what became the winning run in a 6-5 victory.

Toronto won Game 4 to take a 3-games-to-1 lead but Kansas City stormed back to win the series in seven games.

“I’m not going to try to do what George does. Nobody can,” Balboni told the Associated Press before Game 1 of the World Series against the Cardinals. “I’m just going to try to be myself, to stay within myself, and get some important hits. Even if I don’t hit one home run, I’ll be satisfied if I can just get important hits and help the team.”

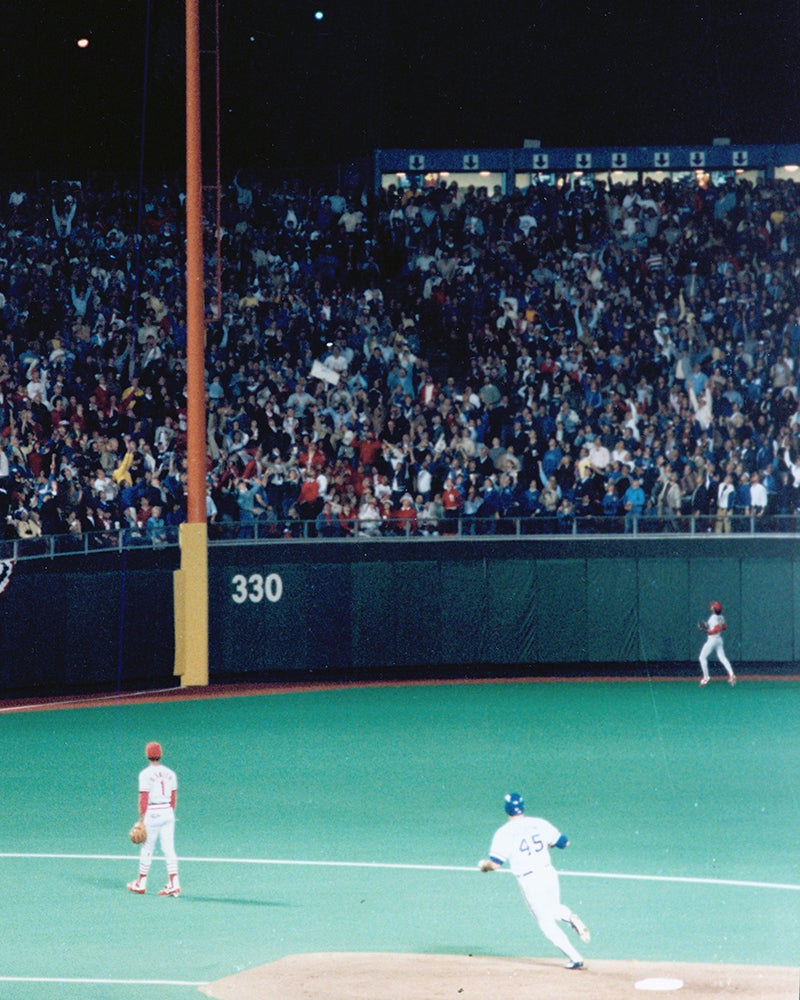

In the World Series, Balboni fulfilled his wish by hitting safely in six of the seven games against St. Louis. All of his hits were singles – the biggest of which came in Game 6 when he followed the Jorge Orta play in the ninth inning (Orta was called safe on an infield single leading off the frame despite TV replays showing that he was out) with a single to left field that put runners on first and second with no one out and the Cardinals clinging to a 1-0 lead. Onix Concepción pinch-ran for Balboni and later scored on Dane Iorg’s single – a hit that also plated Jim Sundberg to give Kansas City a 2-1 victory and extend the World Series to Game 7.

Balboni had two hits and two RBI in the final game as Kansas City won 11-0 to clinch the title.

By the time the spring of 1986 arrived, Balboni’s position on the Royals was as secure as anyone who was not named George Brett. Even with the strikeouts.

“I can’t really eliminate (the strikeouts),” Balboni, who won a 1986 salary worth $525,000 in arbitration, told the Fort Myers (Fla.) News-Press. “And it would be ridiculous to try. I’d have to give up a lot and it’s not worth it.

“Maybe I can cut down on the strikeouts, stop swinging at as many bad pitches. But I’m more concerned with what I do when a man is on base.”

Balboni spent most of the 1986 season in the lower half of the Royals’ lineup until injuries forced him into the cleanup spot late in the year. Kansas City was unable to recapture the magic of 1986, finishing in third place in the AL West with a 76-86 record. Howser was diagnosed with a brain tumor during the season and stepped aside after managing the American League in the All-Star Game.

Balboni finished the year batting .229 with 29 home runs and 88 RBI – all accomplished in just 138 games when back problems sidelined him for the last three weeks of the season.

Then in 1987, Kevin Seitzer started at first base on Opening Day as Balboni transitioned to a DH role. During the season, Seitzer and Brett switched positions – with Brett moving from third base to first base – and Balboni was limited to 55 games at first with another 52 at DH. The Royals had signed Balboni to an incentive-laden deal for 1987 – one worth $100,000 in base salary and another $525,000 based on appearances. Balboni earned all the incentives but appeared in only 121 games, batting .207 with 24 homers and 60 RBI.

The Royals non-tendered Balboni after the season after finding no takers in the trade market.

“We tried very diligently to find a club that would have some interest in him,” Royals general manager John Schuerholz told the Scripps Howard News Service. “There was none.”

But the Royals brought Balboni back for 1988 on a one-year deal worth $350,000, and Balboni started at first base on Opening Day, with Seitzer at third base and Brett at DH. But the Royals signed Bill Buckner on May 13 after he was released by the Angels, and at the time Balboni was hitting .163 with two home runs and five RBI. Two weeks later, the Royals released Balboni.

He signed with the Mariners on June 1 and played in 97 games with Seattle, hitting 21 homers and driving in 61 runs.

“I’m just happy to be playing,” Balboni told the AP in August. “I don’t care what other people think. That doesn’t matter to me. I’m just happy to have a job.”

Now about two weeks short of enough service time to become a free agent, Balboni returned to arbitration and won an $800,000 salary from the Mariners for 1989, a victory that frustrated a Seattle front office that offered only $500,000. On March 27, Seattle traded him back to where he started – sending a minor leaguer to the Yankees in exchange for their former heralded prospect.

“I wasn’t surprised something happened, but I was surprised I was traded,” Balboni told the Hartford Courant after the deal. “I never had anything bad to say about the Yankees. It’s hard to get through their system. But once you make it, they’re great.”

Balboni filled an immediate need for the Yankees, whose lineup lost much of its teeth when Dave Winfield was sidelined for the season with a herniated disc in his back three days before the trade.

“Our right-handed lineup is not something that scared a whole lot of people,” Yankees manager Dallas Green told the Courant. “Getting right-handed power was our primary need since Winfield went down.”

Balboni appeared in 110 games in 1989 – mostly as a DH – batting .237 with 17 homers and 59 RBI. Now eligible for free agency, Balboni quickly returned to the Yankees on a two-year deal (with a club option for 1992) worth a reported $2 million.

But in his age-33 season, Balboni saw his production decline. He batted .192 in 116 games in 1990, striking out 91 times in 266 at-bats while hitting 17 home runs and driving in 34 runs.

On April 1, 1991, the Yankees released Balboni.

“Financially, I don’t have to worry about my family,” Balboni told Gannett News Service while choking back the emotions. “That’s why it’s easier to walk away. But I’ll miss the guys.

“I could see it coming. I wasn’t playing very much. I wasn’t doing very much.”

But Balboni’s playing days were not over. He signed as a free agent with the Texas Rangers on June 2 and reported to Triple-A Oklahoma City, where he hit 20 homers and drove in 63 runs in 83 games.

“I didn’t like the way it ended,” Balboni told the Fort Worth Star-Telegram. “I knew I could still play, still help a team.”

Balboni returned to Oklahoma City in 1992 and led the American Association with 30 home runs while totaling 104 RBI in 117 games. But the Rangers made it clear that they were not interested in bringing Balboni back to the big leagues.

“Basically, we’re giving Steve a forum to showcase his talent,” Rangers general manager Tom Grieve told the Star-Telegram. “He’s free to go to another major league team at any time.”

With the National League expanding to 26 teams in 1993, Balboni hoped he might get another chance. But with no DH in the National League, neither the Marlins nor the Rockies showed interest.

He came back to Oklahoma City for a third season, this time hitting 36 home runs and driving in 108 runs in 126 games and earning a spot on the American Association All-Star team for the second straight year.

On Aug. 30, the Rangers brought Balboni back to the big leagues. It came just days after the Oklahoma City 89ers held Steve Balboni Night in appreciation for their slugger.

He appeared in two games with the Rangers down the stretch, including a start at DH in Texas’ next-to-last game of the year where he went 3-for-4 with three singles against the Royals. It would be the last games of his career.

He signed with the Royals as a free agent on Jan. 27, 1994, but Kansas City cut him on March 31. He decided that this time he would walk away from the game.

“That’s it. I’ll go home,” Balboni told the Kansas City Star. “It’s kind of a relief almost. I’ve been kind of hanging on for three years now. It’s finally over.

“I can’t play minor league ball anymore. It wouldn’t have been fair to the club, to me, to my family. I pushed it to the limit last year. I couldn’t do it again.”

Balboni soon joined the Royals coaching ranks, working as a minor league hitting instructor from 1998-2000 before managing with the Expos at Class A Vermont in 2001. He even visited the Hall of Fame that year when Vermont played New York-Penn League rival Oneonta, located about 30 minutes south of Cooperstown.

But managing was not for Balboni.

“I’m not sorry I took the job at all,” Balboni told the Burlington (Vt.) Free Press after his team went 28-47. “It is not something I would do again.”

Over 11 big league seasons, Balboni hit .229 with 181 home runs, 495 RBI and 856 strikeouts. Combine that with his 239 minor league home runs, and Balboni totaled 420 long balls over 16 seasons.

It is a resume that tells the story of a player who would not give up until he got his shot.

“There are a lot of players who get opportunities and don’t do anything about it,” Dick Howser told the Fort Myers (Fla.) News-Press in the spring of 1986. “Steve Balboni has done something about it.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum