- Home

- Our Stories

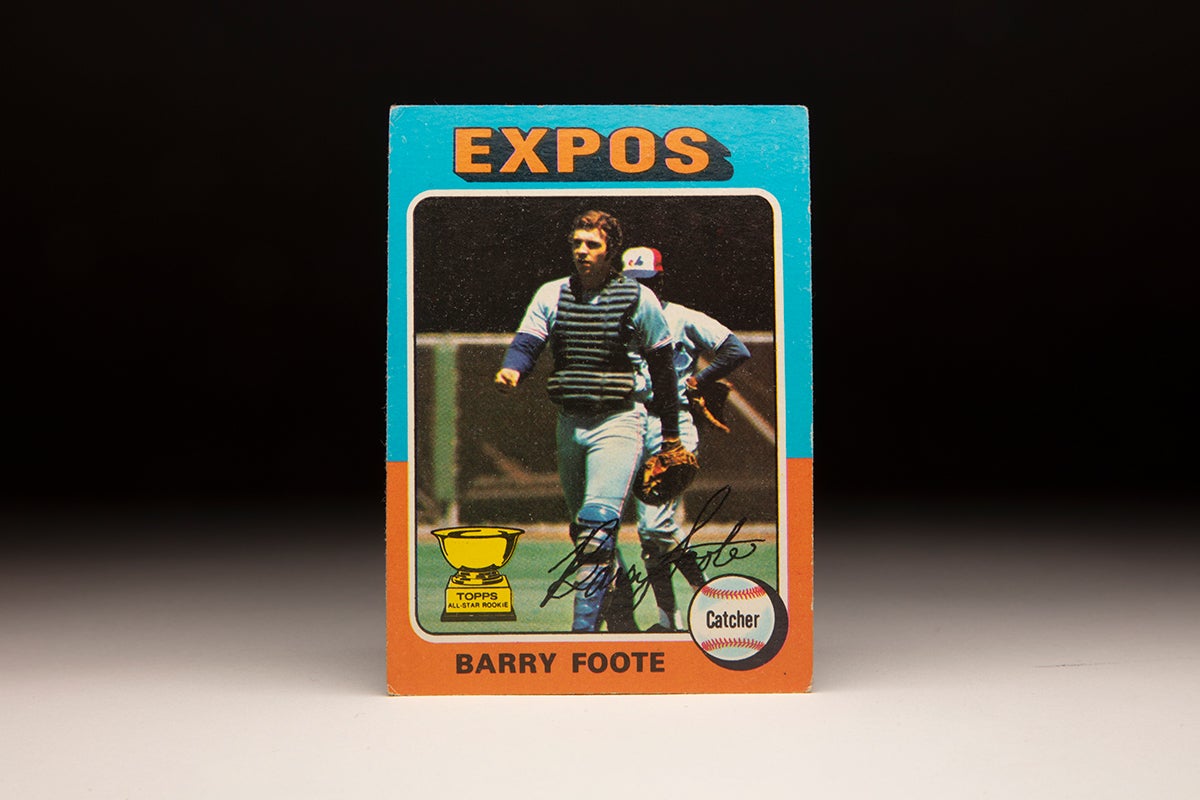

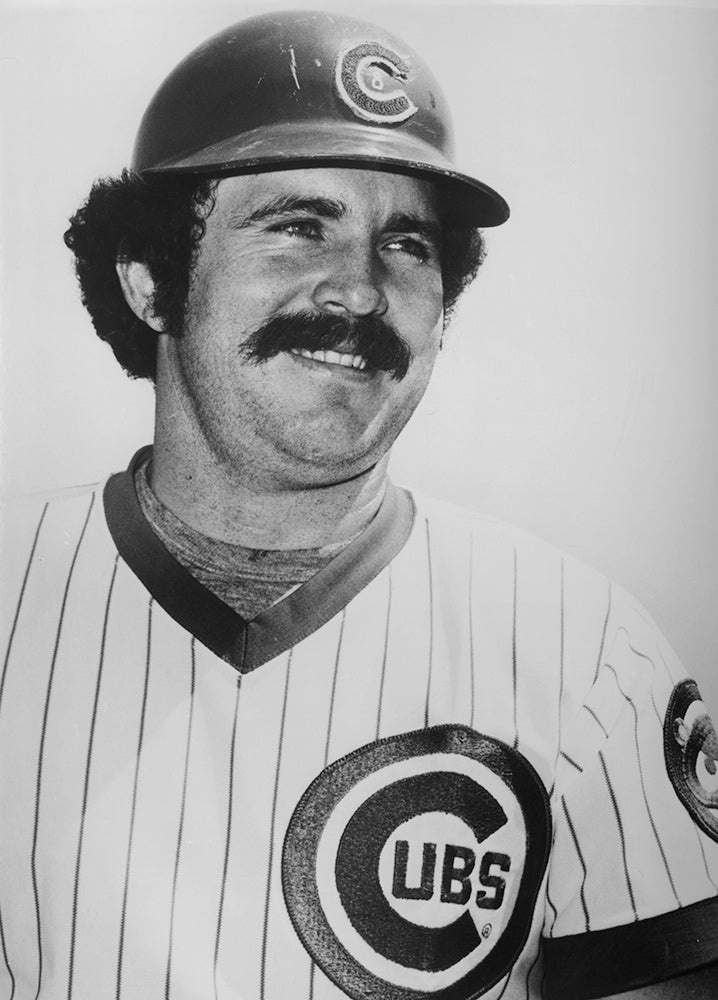

- #CardCorner: 1975 Topps Barry Foote

#CardCorner: 1975 Topps Barry Foote

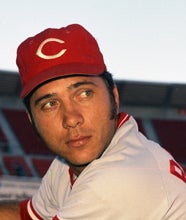

Gary Carter was one of the most celebrated catchers in history, becoming just the eighth backstop to be elected to the Hall of Fame by the Baseball Writers’ Association of America.

Why, then, was Carter starting in right field for the Montreal Expos on Opening Day in 1975? Because the incumbent catcher, Barry Foote, was being compared to some of the best to have ever played the game.

And while Foote did not live up to those expectations, he played 10 years in the majors and later served as a respected coach and minor league manager.

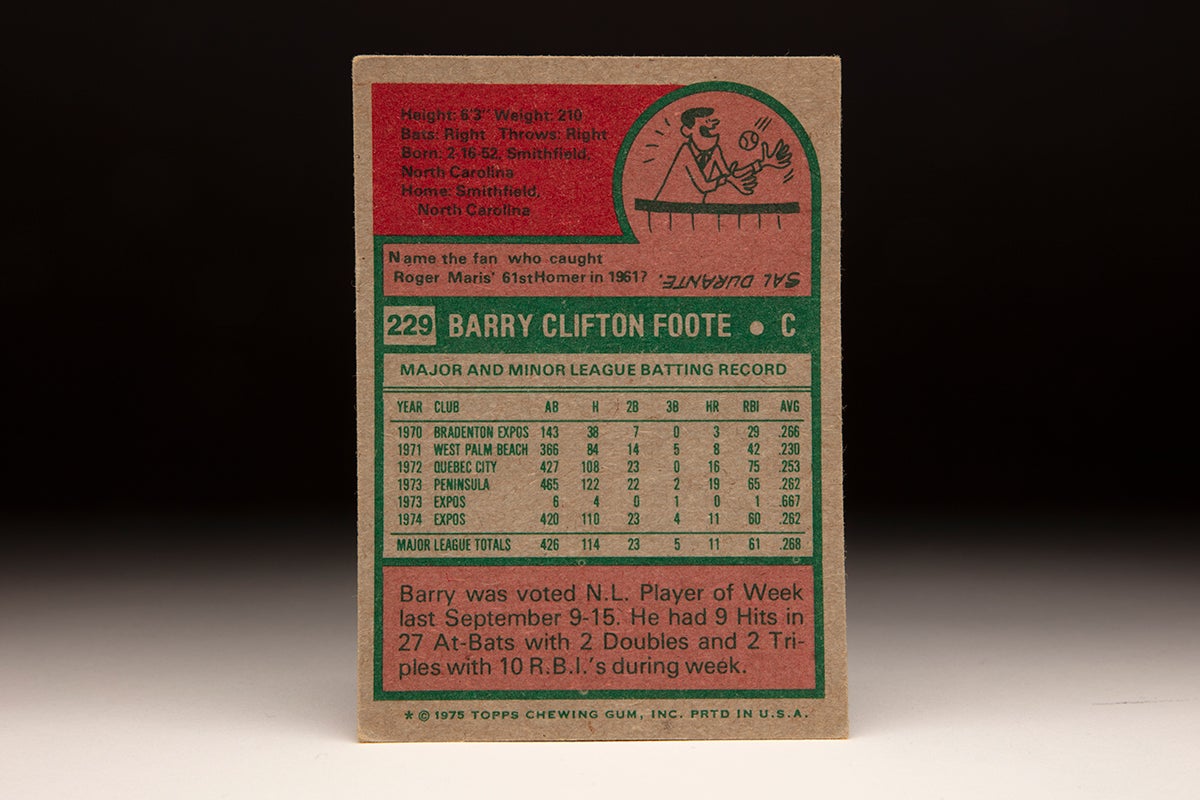

Barry Clifton Foote was born Feb. 16, 1952, in Smithfield, N.C. His father, Ambrose Clifton Foote, was a pitcher in the minor leagues from 1948-54 and spent time in the Pirates organization.

“(My father) taught me most of the things I’ve learned and worked hard practicing with me,” Barry Foote told the Associated Press. “(I’ve been playing baseball) since I was old enough to pick up a baseball and a bat.”

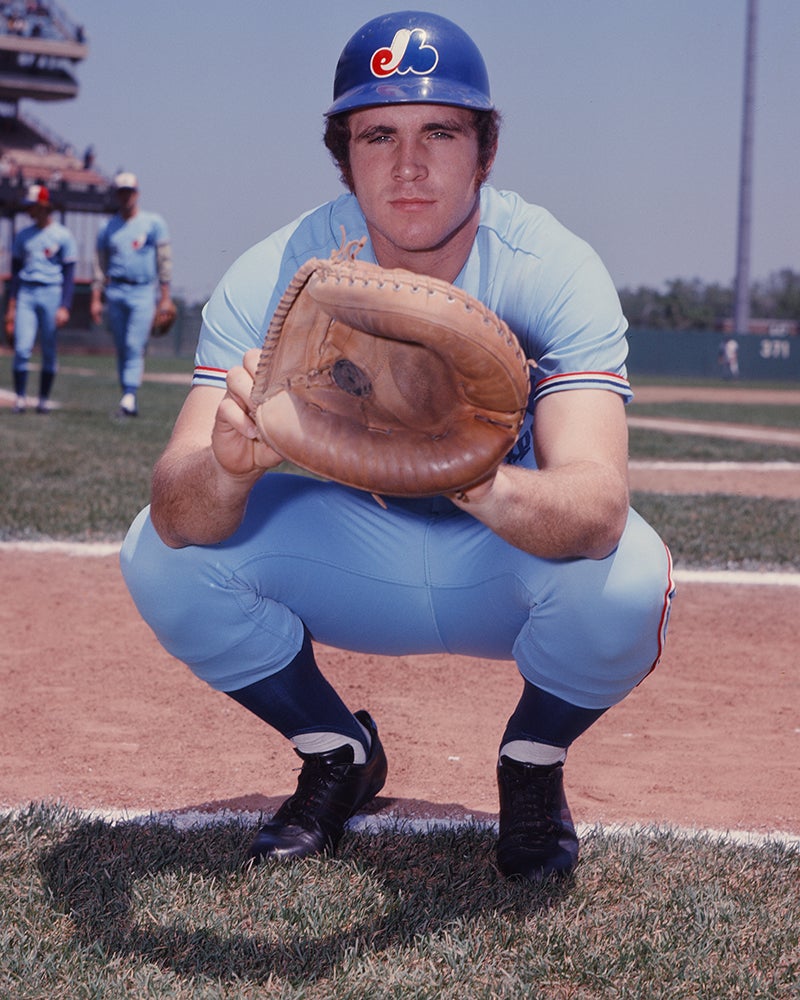

A three-sport athlete at Smithfield-Selma High School, Foote hit .575 as a 6-foot-3, 210-pound senior – like many pro hopefuls, he switched to catcher late in his high school career to try to fast-track himself to the big leagues – and was selected with the third overall pick in the June 1970 MLB Draft by the Montreal Expos one day after he graduated.

“I was going to North Carolina State on a football scholarship (after playing quarterback and linebacker in high school) before I signed with Montreal,” Foote told the Palm Beach (Fla.) Post in 1971. “(But) I’ll never regret not trying football. Playing professional baseball is all I’ve ever dreamed about.”

Foote’s play convinced everyone around him that his dreams would come true.

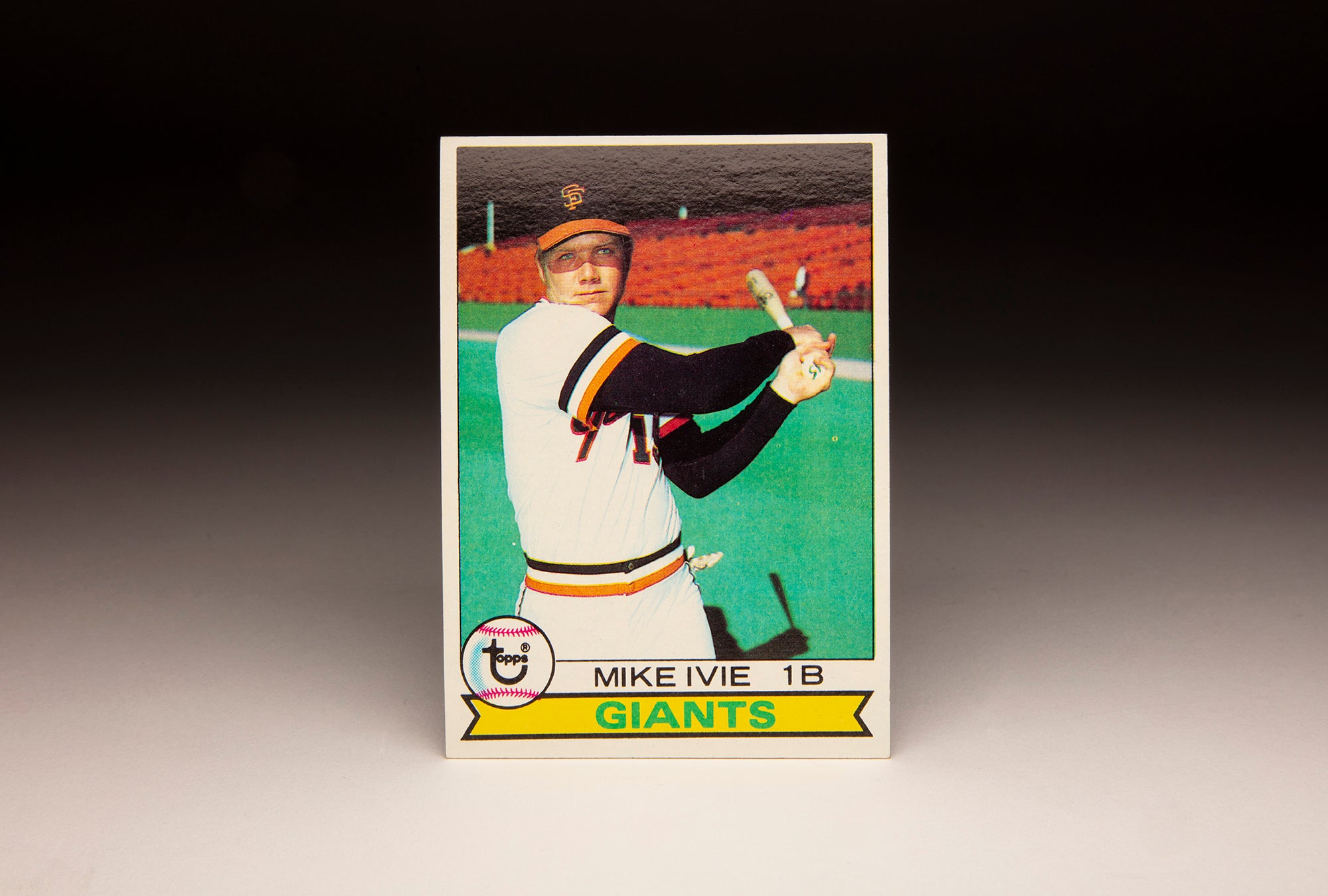

“He certainly has the potential to play major league ball,” Smithfield-Selma baseball coach Virgil Payne, who managed Ambrose Foote while he was in the minors, told the AP about Barry Foote, who was picked behind only Mike Ivie and Steve Dunning and just ahead of Darrell Porter.

Montreal scouting director Mel Didier told the AP that Foote had “a chance to be another Johnny Bench” – sky-high praise during a year where Bench would be voted the National League’s Most Valuable Player.

The Expos sent Foote to their Gulf Coast League team in Sarasota, Fla., where he hit .266 with a .379 on-base percentage in 46 games. He played in the Florida Winter Instructional League following the season and then stayed in the Sunshine State in 1971, batting .230 with eight homers and 42 RBI in 115 games for Class A West Palm Beach.

In 1972, Foote was assigned to the Quebec Carnavals of the Double-A Eastern League, where he hit .253 with 16 homers and 75 RBI – earning first-team all-league notice. He moved up to Triple-A in 1973, hitting .262 with 19 homers and 65 RBI for Peninsula of the International League and winning a vote that earned him the title of the top catcher in Triple-A.

The Expos brought Foote to Montreal in September, and he recorded four hits in six appearances as a pinch-hitter before heading to Puerto Rico to play winter ball.

“In Puerto Rico, I saw him play five games and (Expos manager) Gene (Mauch) saw him play four,” Expos general manager Jim Fanning, who harbored concerns about Foote’s defensive ability, told the Montreal Star. “He is further advanced than we thought…so much so that he can be our catcher.”

Foote started for the Expos behind the plate on Opening Day in 1974, recorded hits in four of his first five games and hit his first big league homer on April 17 against the Mets’ George Stone – a blast that gave Montreal a 4-3 lead in a game the Expos went on to win 7-4.

Foote began wearing glasses during the 1974 season, which he credited with helping him with the bat. He was hitting .204 in early June when he began experimenting with eyewear.

“I like to think I have improved with experience,” Foote told the Montreal Gazette. “It means something to play for a while and feel that you belong. You look at the statistics, though…yeah, I guess the glasses helped.”

The young Expos were never quite able to get in the race for the NL East title but won 18 of their final 23 games, including a 3-2 victory over the Cardinals on Oct. 1 that dealt a crippling blow to St. Louis’ postseason hopes.

Montreal finished 79-82, and most observers felt Foote was part of a core that would lead the team to a division title.

“(Pitcher) Steve (Renko) and I were talking the other day. We figure that we need a team leader,” Foote told the Montreal Gazette in August of 1974. “We figure it has to be someone who is playing every day and someone who will drive home important runs – give the guys a lift.

“You know, a week or so ago I got a couple of key hits that started us on a winning streak. I started to think: ‘Hey, maybe I can be the leader.’”

Foote finished the 1974 campaign with a .262 batting average, 11 homers, 60 RBI and an NL-best 12 sacrifice flys in 125 games. He also showed off his arm by recording an NL-leading 83 assists. Carter, meanwhile, lit up the International League at Triple-A Memphis, totaling 23 homers and 83 RBI in 135 games – 114 of which came behind the plate.

When the 1975 season dawned, Mauch felt he had to find a way to get Carter’s bat into the lineup.

“I think (Carter) makes the transition to other positions more readily than Barry,” Mauch told the Canadian Press in the spring of 1975. “He’s a little faster. I want Gary Carter to make me play him somewhere.”

Carter, who turned 21 the day after Opening Day in 1975, made it clear he wanted to remain a catcher.

“Barry had a fine season and I’m glad for him,” Carter told the Gazette. “I enjoy being around him. There is no animosity. He’s not only a fine catcher but a fine person. That makes it more fun because the competition will be keener.

“I want to catch. Barry is in for a battle.”

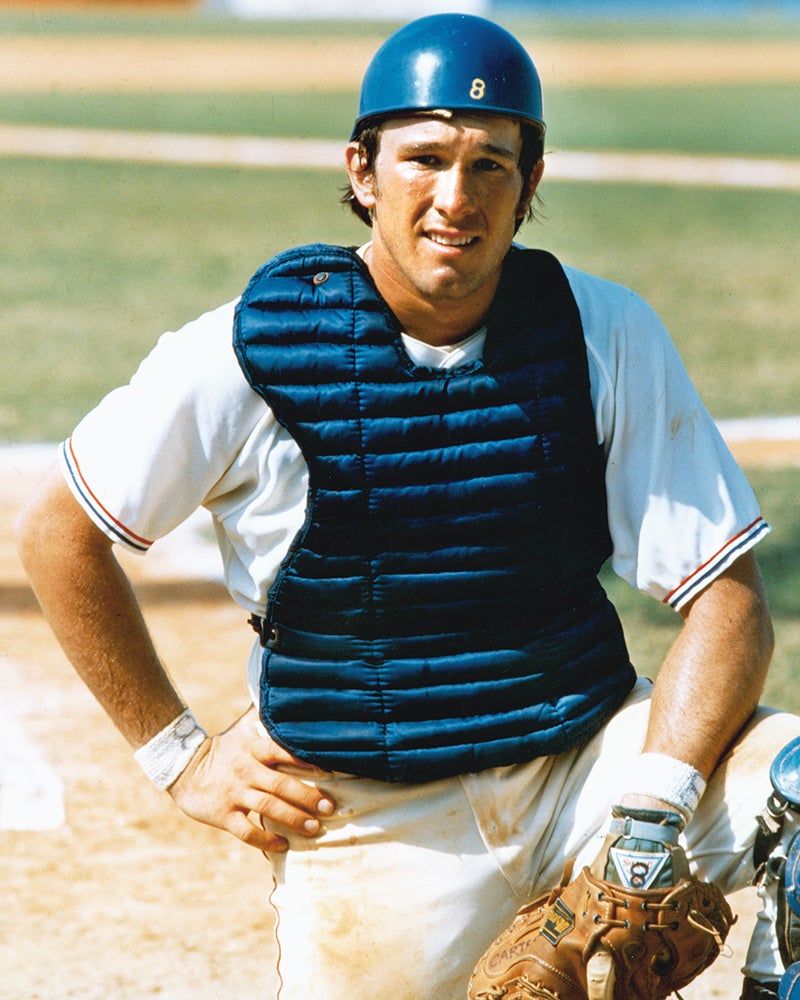

It was Carter, however, who did battle – with outfield walls as he tried to master right field. By May, Carter was catching a couple times a week when Foote rested. Then in the final month of the season, Foote’s left knee stiffened up during a game against Pittsburgh on Sept. 7.

“I can’t say the knee has been bothering me,” Foote told the Gazette. “I don’t know what to think about this season at all.”

Carter took over as the starting catcher after surgery was deemed necessary on Foote’s knee. Carter finished the season hitting .270 with 17 homers and 68 RBI in 144 games.

Foote, meanwhile, hit just .194 with seven homers and 30 RBI.

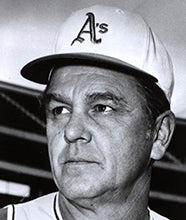

The Expos won four fewer games in 1975 than the year before, costing Mauch his job. Karl Kuehl took over and Foote had an excellent spring in 1976, winning the Opening Day job behind the plate. Carter once again began the season in right field.

But Foote had recurring knee problems during the season, and Carter suffered a hand injury that limited him to just 91 games – 60 of which came behind the plate. Foote hit .234 with seven homers and 27 RBI in 105 games, Montreal went 55-107 and Dick Williams replaced Kuehl as manager.

A no-nonsense manager skippering his fourth big league team, Williams made it clear that he preferred Carter behind the plate over Foote. His pitchers largely disagreed and had stated that publicly for a couple of years. But Williams liked Carter’s enthusiasm and willingness to challenge his pitchers.

“Dick told me yesterday. He said: ‘You’re my No. 1 catcher. Barry will catch day games after night games and the second half of doubleheaders,’” Carter told the Montreal Star on April 8, 1977 – his 23rd birthday. “What can I say? It’s what I’ve been looking for.”

Foote, meanwhile, was the subject of trade rumors almost from the first day of Spring Training. He was linked to the Orioles in a deal that would have brought pitcher Ross Grimsley to the Expos, but the trade was never consummated.

The Expos renewed Foote’s contract for 1977 with the maximum-allowed 20 percent pay cut, prompting Foote to play the season unsigned. With the drama stretching on throughout the spring, the Expos finally found a trade partner and sent Foote to the Phillies on June 15 – the trade deadline – along with Dan Warthen in exchange for Tim Blackwell and Wayne Twitchell.

“The only thing I’m bitter about is the 20-percent pay cut,” Foote told the Star. “It’s not as if I’m making $100,000 and they’re saving $20,000. It’s a slap on the wrist.”

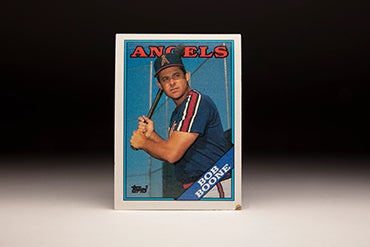

Phillies manager Danny Ozark welcomed Foote as a “proven” player. But Foote could tell that playing time would be scarce behind Bob Boone, 1976 NL All-Star, and Tim McCarver, who was Steve Carlton’s personal catcher.

“There’s anticipation and excitement about playing for a pennant contender,” Foote told the Morning News of Wilmington, Del. “I’m happy to be with a club that has confidence in me. I just hope I get to play here.”

But as the third-string catcher – in an era where most clubs carried three catchers on the active roster – Foote appeared in only 18 games the rest of the season, which was three more than he appeared in for Montreal that year. Over 33 games in 1977, Foote batted .235. The Phillies won the NL East title but Foote did not play in the NLCS loss against the Dodgers.

Foote could have explored free agent possibilities after the season. But the Phillies wanted Foote back – so much so that they signed him to a four-year deal worth a reported $680,000 that could have maxed out at more than $800,000 if Foote appeared in a certain number of games. Foote agreed to the contract even though he knew he would be a backup to the durable Boone.

“I’ve made my bed and I’ve got to sleep in it,” Foote told the Philadelphia Daily News in the spring of 1978. “I had my choice. I could have gone to several clubs. But they would have been also-ran clubs.

“I really don’t know how I’ll be used. Hopefully, I’ll get in more games. I hope that they want to get me in more games.”

Ultimately, Foote appeared in only six more games in 1978 than he did the previous year, batting .158 with nine hits in 58 plate appearances. The Phillies again won the NL East and again lost to the Dodgers in the NLCS, with Foote getting one at-bat in the postseason as a pinch-hitter in Game 2. He struck out against Tommy John in a game the Dodgers won 4-0.

Foote, though, continued to burnish his reputation as one of the toughest catchers in the game. In 1996, Brewers manager Phil Garner referenced Foote – who by that time had been retired as a player for almost 15 years – when he argued against head-first slides into home plate.

“The reason it became vogue is because catchers stopped blocking home plate,” Garner told reporters. “I’ll tell you something: If you ever tried to slide head-first against Mike Scioscia, Johnny Bench, Barry Foote…those guys would kill you. They’d take that knee and stick it right in your neck. It’s a no-win situation.”

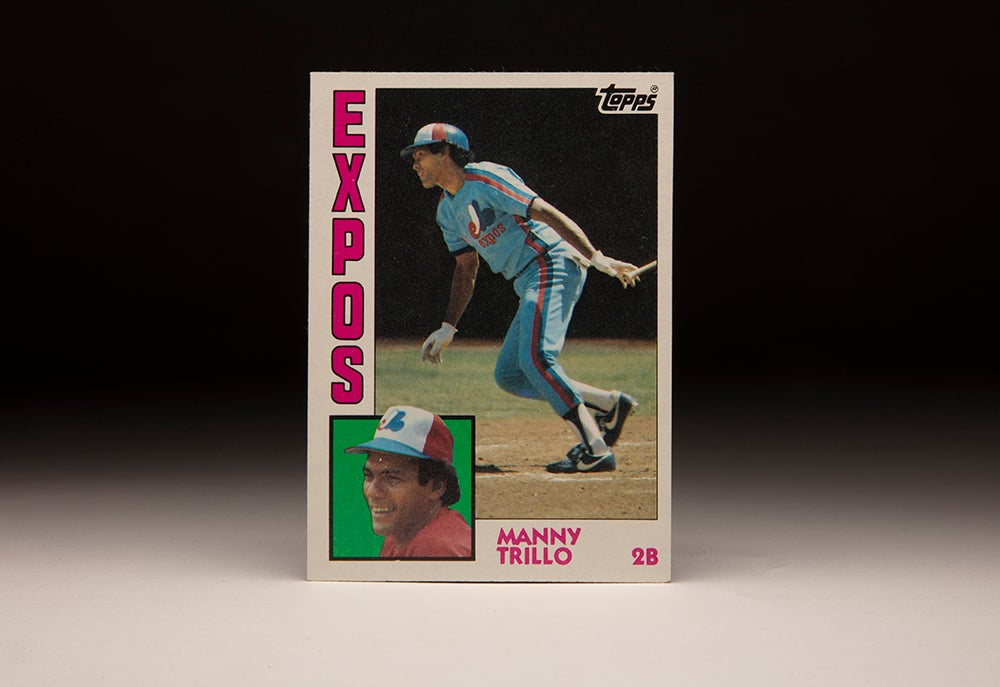

But on Feb. 23, 1979, the Phillies decided Foote was a luxury they could not afford and traded him to the Cubs with Derek Botelho, Jerry Martin, Ted Sizemore and a minor leaguer in exchange for Greg Gross, Dave Rader and Manny Trillo.

“Great deal, simply great, I’m really excited about it,” Cubs manager Herman Franks told the Associated Press. “Yes, I’d say Foote is the key guy in the deal, but, hey, this Martin can play too. We got ourselves three regulars.

“I’ll tell you this, we finally got ourselves a catcher.”

Franks made Foote his No. 1 catcher, and Foote responded with his best season since 1974 – batting .254 with 16 home runs and 56 RBI in 132 games. He ranked second among NL catchers in games (129 behind the plate) and putouts (713). He also led the league with 17 errors.

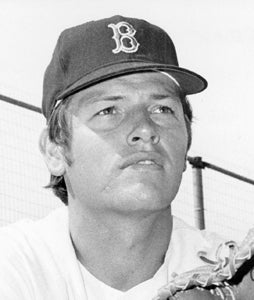

The Cubs, however, extended Foote’s contract through the 1984 season, adding a reported $600,000 to the deal. And Foote was still in demand throughout the game: The Red Sox reportedly tried to trade for him in the spring of 1980, offering Butch Hobson in exchange as a hedge against Carlton Fisk’s sore arm. But the Cubs held onto Foote, and he had his best day at the plate in the majors on April 22 against the Cardinals at Wrigley Field, going 4-for-6 with two homers and eight RBI – including a walk-off grand slam in the ninth after a solo homer in the eighth – in a 16-12 win.

“I had some good years in the minors but nothing like this,” Foote told the AP after the game. “I can’t remember. I’m not much for stats. That’s not my game.

“But I know one thing for sure: That’s the first time I ever hit successive home runs.”

It was the high point of a season where Foote played in just 63 games due to back trouble. He hit .238 and a third of his home runs and almost 29 percent of RBI on the season came in that one game against the Cardinals.

“I don’t think the Cubs care about winning,” Foote told the Raleigh (N.C.) Sports Club – Foote made his offseason home in Raleigh – in a story reported by the Durham (N.C.) Morning-Herald. “They want to get rid of all the high-salaried players. They go into the thing with the asinine feeling that we finished in last place and can’t get any better.”

Foote soon found himself with baseball’s biggest spenders. On April 27, 1981 – after coming to the plate 26 times over nine games and failing to get a single hit – Foote waived the no-trade clause in his contract and was sent to the Yankees in exchange for pitcher Tom Filer and cash.

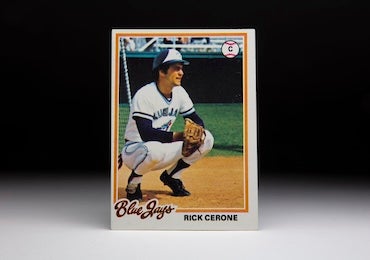

Yankees starting catcher Rick Cerone was sidelined at the time with a broken thumb, and Foote was brought in to fill the void. He assumed most of the team’s catching duties in May but went to the bench after Cerone returned, finishing the season with six homers and 10 RBI in 40 games for New York while batting .208.

Foote played in each of the three rounds of the postseason for the Yankees, pinch-hitting three times and entering another game as a defensive replacement. He recorded a hit in Game 3 of the ALCS vs. Oakland – a ninth-inning single off Tom Underwood that extended a Yankees rally – and struck out in his only World Series at-bat in Game 4 against the Dodgers as New York fell in six games.

Foote appeared in just 13 games in 1982 before being designated for assignment on July 15 when Cerone returned from a stint on the disabled list. Foote asked to go to Triple-A Columbus and was granted permission. He appeared in seven games with the Clippers and returned for four more games with the Yankees that year – the last four of his big league career.

On March 25, 1983, the Yankees released Foote even though they were obligated to pay him the $500,000 they owed him through the 1984 season. They kept Foote in the organization, however, making him their National League scout and signing him to a four-year deal in that role.

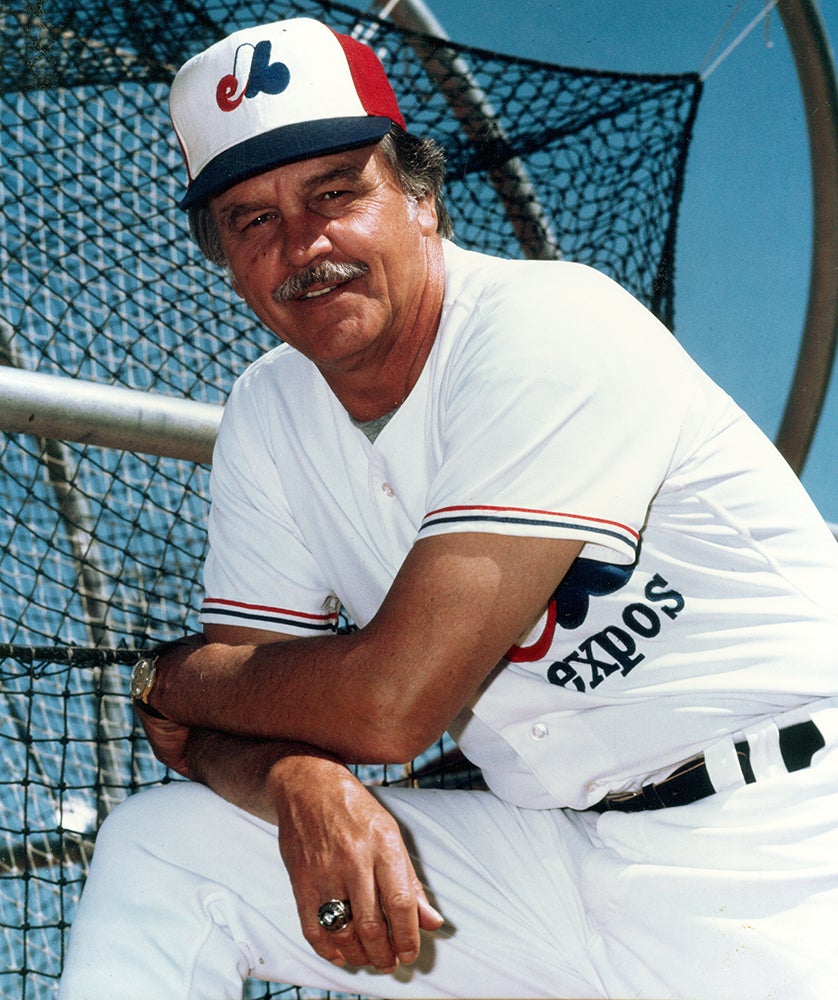

But in 1984, the Yankees’ brass changed their minds and named Foote as their manager of Class A Fort Lauderdale in the Florida State League. The team won the FSL title and Foote moved up to Double-A Albany-Colonie in 1985, where he again led his team to a first-place finish.

In 1986, Foote managed Triple-A Columbus before moving on to the Blue Jays organization in 1987, managing the team’s South Atlantic League team in Myrtle Beach, S.C. He managed Double-A Knoxville the next two seasons before landing a job as a White Sox coach under Jeff Torborg from 1990-91. Foote followed Torborg to the Mets and was a coach there in 1992-93.

Foote’s son, Derek, was a sixth-round draft choice by the Braves out of Wake Forest University in 1994 and played four seasons with Atlanta in the minors.

Over 10 big league seasons, Barry Foote hit .230 with 57 homers and 230 RBI. And though he never made an All-Star team or got even one vote in balloting for a major Baseball Writers’ Association of America award, Foote maintained a reputation as one of the most sought-after – and well paid – catchers of his era.

If it wasn’t for a future Hall of Famer, Foote’s career might have looked very different.

“We got into a situation in Montreal where I was fed up,” Foote told the Philadelphia Daily News in 1978 about his competition with Gary Carter. “We had two young catchers who wanted to catch everyday and there’s no way that can happen.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum