#CardCorner: 1978 Topps Rick Cerone

He stepped into the role of one of the most beloved Yankees of the 1970s, and Rick Cerone initially seemed poised to add to the legacy of championship catchers in the Bronx.

But while his New York career fell short of a title, Cerone spent a total of 18 years in the big leagues as a durable catcher whose skills were often in demand.

Richard Aldo Cerone was born May 19, 1954, in Newark, N.J. An all-round athlete during his youth, Cerone starred in baseball, football and fencing at Essex Catholic High School before initially committing to the University of Rhode Island.

“I had 60 football scholarship (offers) and none for baseball,” Cerone, who played quarterback for Essex Catholic, told the Asbury Park Press. “I wanted to play football and baseball in college and nobody in the big schools would let you.”

Rhode Island promised Cerone a chance to play both sports, but before enrolling Cerone was talked into playing American Legion baseball that summer by a coach named Mike Sheppard. Later that summer, Sheppard was hired as the new head coach at Seton Hall University – and Cerone changed his mind and decided to stay closer to home and play for Sheppard again.

“That decision,” Cerone told the Asbury Park Press, “changed my entire life.”

With the Pirates, Cerone began seeing regular playing time as a freshman and batted .339. He followed that up with seasons hitting .326 and .410, finishing his career with 26 home runs and 102 RBI in 114 games while winning All-American honors and being named an academic All-American. He led the Pirates to the College World Series in both 1974 ad 1975.

Enamored with his bat and his top-shelf throwing arm, the Cleveland Indians took Cerone with the No. 7 overall pick in the 1975 MLB Draft.

“I was so impressed with him that I thought he could play in the major leagues right then,” said Jeff Torborg, who was a coach with the Indians when Cerone was drafted.

The Indians sent Cerone to Triple-A Oklahoma City, where he batted .250 with two homers and 13 RBI in 46 games before being called up to the majors on Aug. 15 when catcher John Ellis was sidelined with a hamstring injury.

Two days later, Cerone made his big league debut when he entered a game against the Twins in the seventh inning. He came to bat in the ninth and lined out against Bill Campbell.

“It’s tough to get up for games every day in Oklahoma City, but up here it’s been pretty easy,” Cerone told the Associated Press. “I think it’s a little too soon for me to be producing up here. What I mean is that it took me four weeks at Oklahoma City to get used to the pitching.”

Cerone finished the season batting .250 in seven games for Cleveland, then returned to Seton Hall and earned his degree in the spring of 1976.

“I wanted to be a college graduate,” Cerone told the Asbury Park Press. “To me, it was very important.”

The Indians’ Triple-A team was relocated to Toledo in 1976, and Cerone played 96 games with the Mud Hens that year, hitting .254 with 11 homers and 49 RBI before once again appearing in seven games with the Indians late in the season.

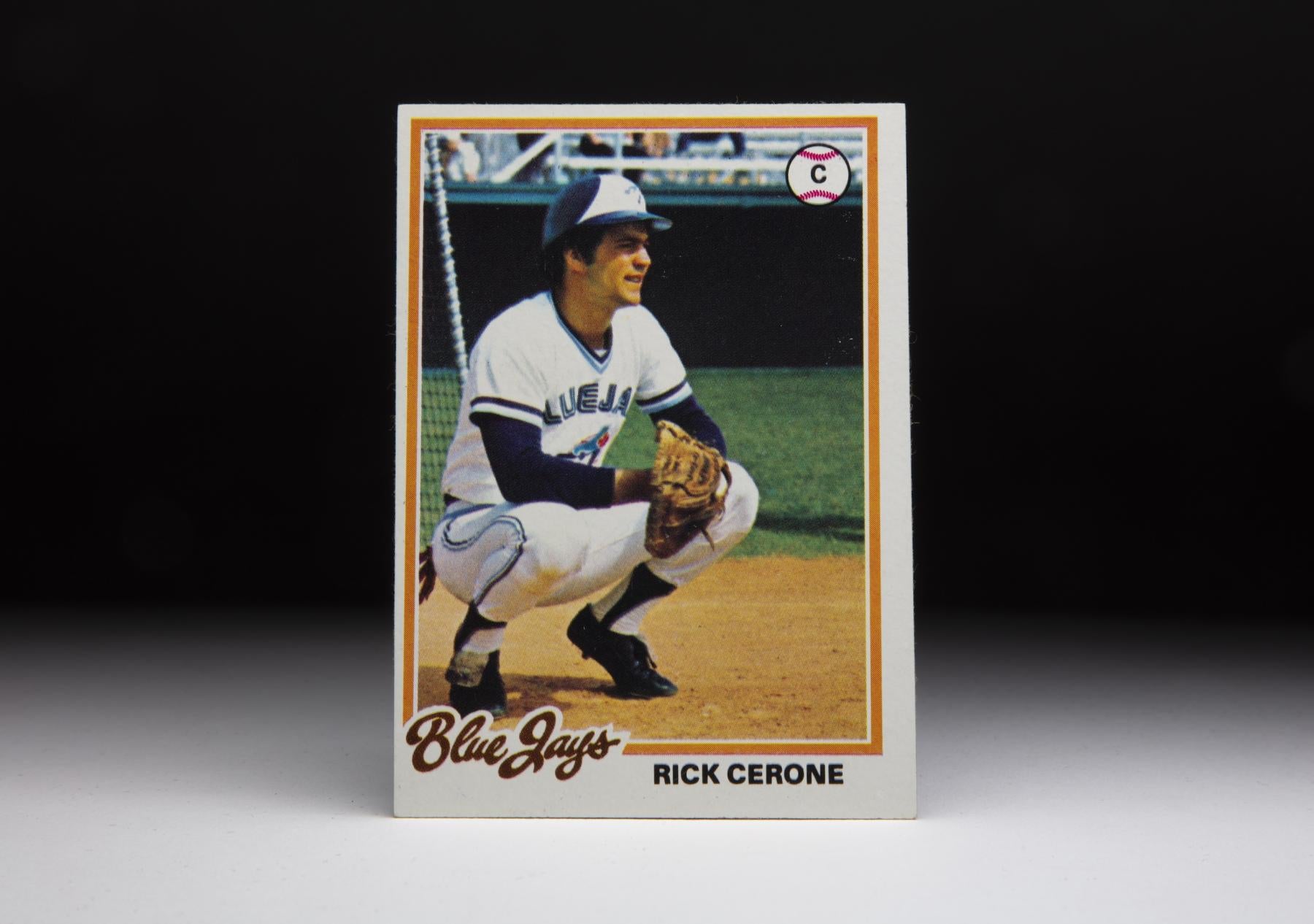

On Dec. 6, 1976, Cleveland traded Cerone and outfielder John Lowenstein to the Blue Jays for 37-year-old Rico Carty, who had been selected by Toronto from the Indians one month earlier in the Expansion Draft. Carty had become a fan-favorite with Cleveland during the previous two-and-a-half years, hitting .310 with 13 homers and 83 RBI as the team’s primary DH in 1976. But Carty had no role on an expansion team like the Blue Jays, and the trade brought Toronto a player who many considered one of the top catching prospects in the game.

“We think we made a very good trade for Carty, because catcher’s like Cerone are very valuable,” Blue Jays director of player personnel Pat Gillick told the AP.

And those some talent evaluators still had reservations about whether Cerone would hit, Gillick knew that his defensive ability would stabilize the young Toronto pitching staff.

Cerone made the Blue Jays’ Opening Day roster and was the starting catcher in the first game in franchise history, going 2-for-4 with a double in Toronto’s 9-5 win over the White Sox on April 7. But Cerone broke his right thumb in the season’s second week, sidelining him for all but one game for about five weeks before the Blue Jays sent him to Triple-A Charleston in late May. He would return to Toronto in mid-August and hit .200 in 31 games with the Blue Jays that year.

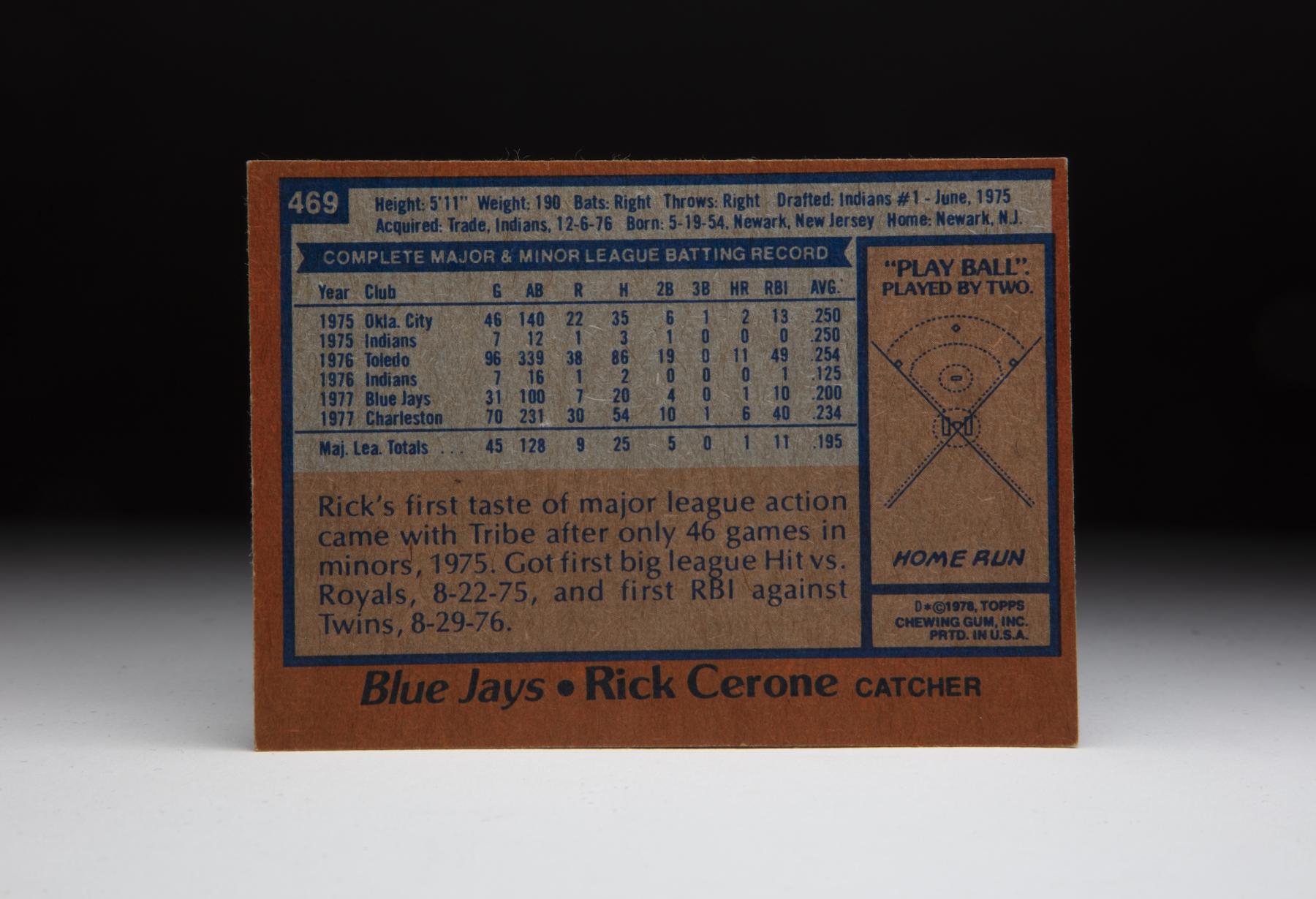

But in 1980, Cerone was the darling of the New York media. He recorded three hits in the season’s third game against Texas, then embraced his first games at Yankee Stadium as a member of the Bronx Bombers.

“I don’t know about kids nowadays, what they think about growing up,” Cerone told the New York Daily News prior to his first game with New York at Yankee Stadium. “But when I was growing up, you wanted to play for the Yankees.”

Cerone’s bat heated up with the weather and he was in the lineup almost every day, hitting .277 with 30 doubles, 14 homers and 85 RBI in 147 games while throwing out an AL-leading 51.8 percent of runners who tried to steal. He finished seventh in the AL Most Valuable Player voting and was one of only five players to receive a first-place vote in balloting won by George Brett.

The Yankees won 103 games and the AL East title but were swept in the ALCS by Brett and the Royals despite Cerone’s .333 effort at the plate.

“It’s hard to accept,” Cerone told the Asbury Park Press after the season-ending loss in Game 3 where Cerone, batting with the bases loaded, no one out and the Yankees behind 4-2 in the bottom of the eighth, lined into a rally-killing double play. “I felt I failed.”

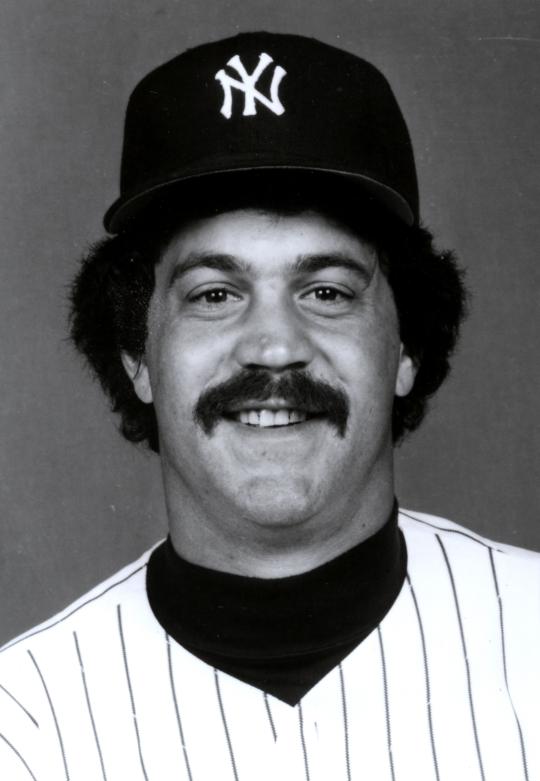

But despite his struggles, Cerone was brought back for the 1983 season, signing a four-year deal worth a reported $2.5 million.

“The Yankees are my team,” Cerone told the Miami Herald on the eve of Spring Training in 1983. “I’ve always wanted to play for them.”

Cerone and Wynegar shared the catching duties in 1983, with Wynegar batting .296 with a .399 on-base percentage while Cerone hit just .220 in 80 games. In 1984, Wynegar got even more playing time as Cerone missed about two months with an elbow injury and appeared in just 38 contests while hitting .208.

On Dec. 5, 1984, Cerone’s time with the Yankees came to an end when he was traded to the Braves in exchange for pitching prospect Brian Fisher.

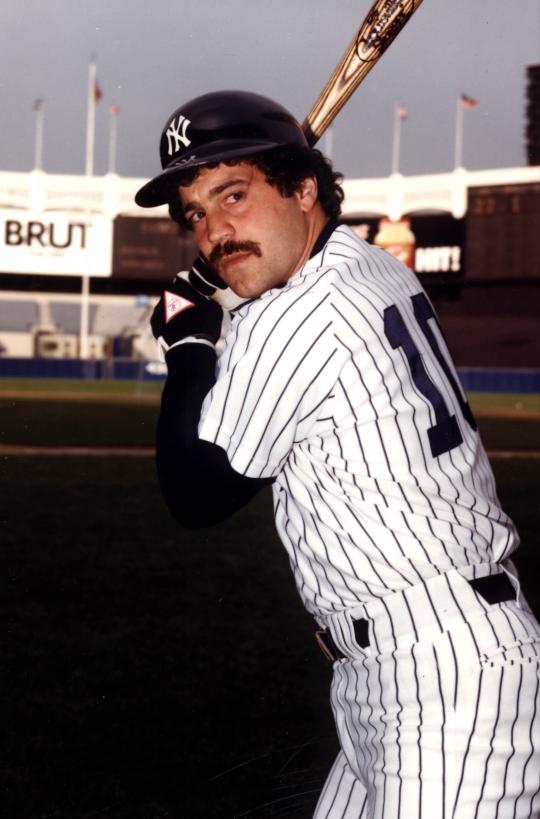

Cerone returned to Boston in 1989 and hit .243 in 102 games. The Red Sox, however, did not offer him a contract for the 1990 season. A day after Boston officially non-tendered Cerone, he signed a two-year, $1.4 million deal with the Yankees – returning for his third stint in New York.

But after hitting .302 in 49 games in 1990, Cerone was designated for assignment on Jan. 13, 1991, as the Yankees made room on the 40-man roster for pitcher Scott Sanderson.

“I don’t have any hard feelings,” Cerone told Gannett News Service after he was released. “I still look back to the winter of ’86. Nobody wanted me and collusion was going on. The only team that wanted me was the Yankees, so I can’t knock the Yankees.”

A week after leaving the Yankees, Cerone signed with the Mets and hit .273 over 90 games in 1991. He hooked on with the Expos in February of 1992. He hit .270 over 33 games but ceded most of the playing time to 38-year-old Gary Carter before being released on July 16.

By August, Cerone had decided to retire.

“My first life is over,” Cerone told The Record of Hackensack, N.J. “My other eight lives are about to begin.”

In retirement, Cerone worked as a broadcaster, in marketing and in real estate. He finished his 18-year big league career with a .245 batting average that included 998 hits and 190 doubles.

It was a career that – for a period of time – saw him become a hometown hero for the game’s most celebrated team.

“If you’re an athlete, you’re competitive – even if you’re playing tennis or Donkey Kong,” Cerone said in 1983. “People say: ‘You’re not a good loser.’ Well, how many good losers do you know?

“I’d rather be a bad winner than a good loser.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum