- Home

- Our Stories

- Fernandomania made it all the way to Cooperstown

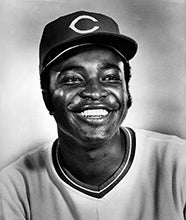

Fernandomania made it all the way to Cooperstown

Nestled in the Mayo Valley, between the coast of the Gulf of California and the Rio Mayo, lies Navojoa, Mexico. Geoglyphs serve as reminders of the Mayan tribes that inhabited the area for centuries, but nowadays the region is primarily known for its agriculture and shrimp farming.

Within Navojoa is the town of Etchohuaquila, home to fewer than a thousand residents but which gained global attention in 1981 as the birthplace of a 20-year-old Dodgers phenom who took baseball by storm.

Eventually, the phenomenon known as Fernandomania made it all the way to Cooperstown.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Official Hall of Fame Apparel

Proceeds from online store purchases help support our mission to preserve baseball history. Thank you!

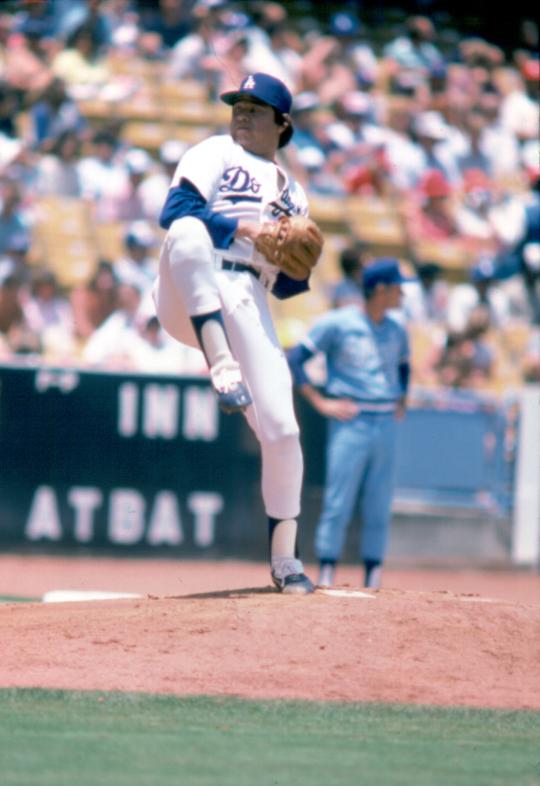

Born the youngest of 12, Fernando Valenzuela looked nothing like the game’s typical aces, with their lanky limbs and imposing height. The left-hander was relatively short and stocky, with a tightly-coiled windup that brought his right knee to his ear and his eyes disconcertingly up to the skies.

He began his professional baseball career at age 17 in the Mexican Center League, which later became a part of the expanded Mexican League. Major league scouts monitored him loosely until 1979, when legendary Dodgers scout Mike Brito glimpsed the youngster’s arm while scouting another player.

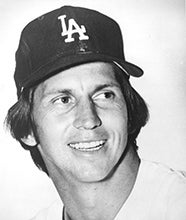

Within days, Los Doyers had signed Valenzuela for $120,000. They brought him up to California, where he joined the Lodi Dodgers, their High-A affiliate. Valenzuela made just a handful of appearances, and then the Dodgers connected him with another young pitcher – Bobby Castillo – to develop an off-speed pitch.

Armed with a new screwball taught by Castillo, Valenzuela made his big league debut the following season at the end of 1980. The 19-year-old made 10 appearances in relief, and didn’t allow a single run, but no one could have guessed what history would hold for both the Mexican lefty and Major League Baseball.

Slated as the Dodgers’ third starter in the rotation, Valenzuela became the Opening Day starter after a last-minute injury sidelined Jerry Reuss. On April 9, 1981, in front of 50,511 fans, the Dodgers faced off against the defending NL West champ Houston Astros and triumphed, thanks to a complete game, five-hit shutout by the rookie from Etchohuaquila.

What followed over his next seven starts is one of the most astonishing eight-game stretches in major league baseball.

Valenzuela won each start and went the distance every time, including five shutouts, four double-digit strikeout outings and a 0.50 ERA.

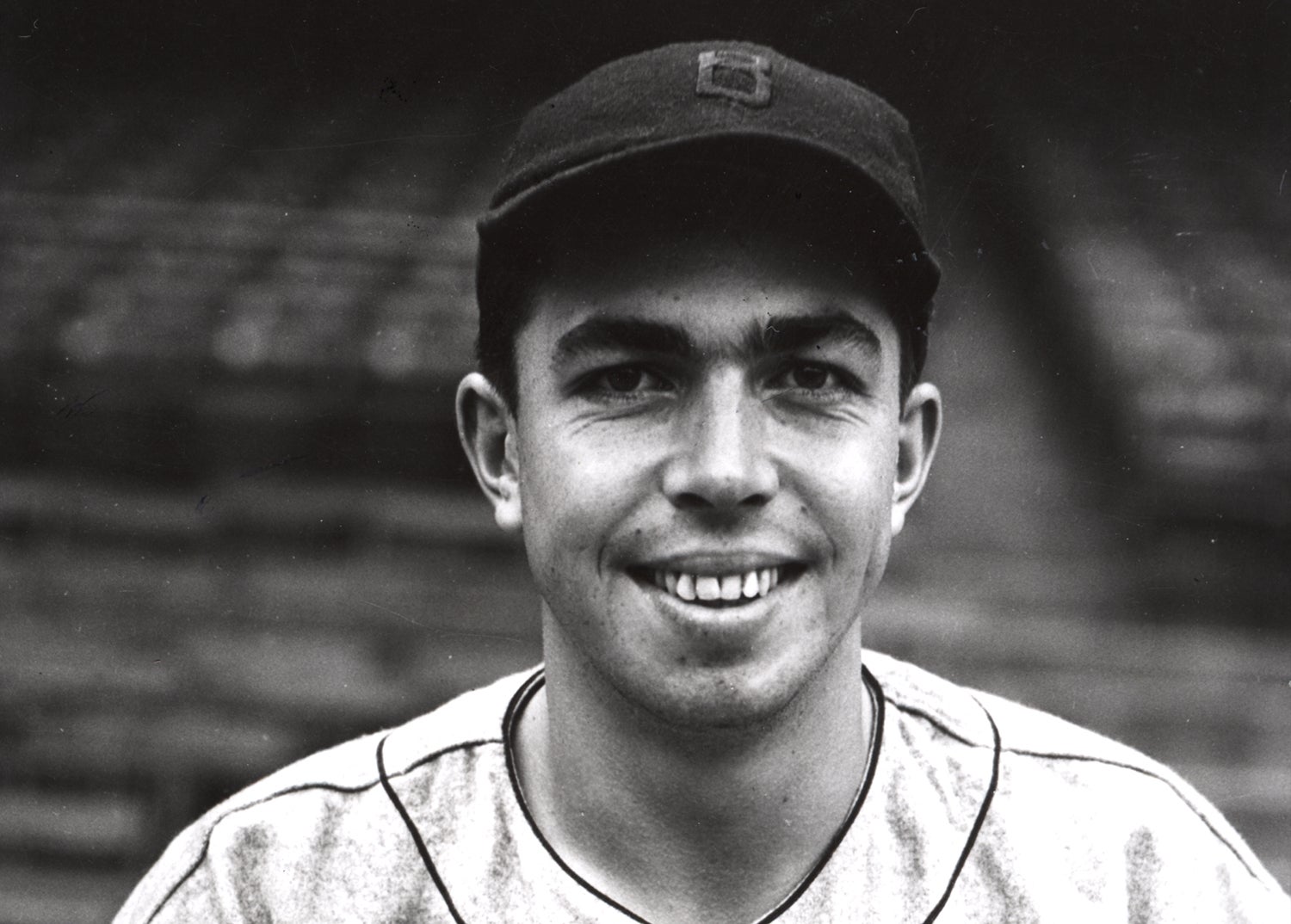

Hall of Famer Carl Hubbell called Valenzuela’s crafty pitch “the best screwball since mine” and Don Sutton was “in awe of” his screwball, while Joe Morgan argued that “The key is his fastball. It’s good enough that you can’t lean on his curve or his screwball.”

Fans began making shirts with Valenzuela’s face on them, radio callers made up songs in his honor and the Los Angeles Times devoted a three-page spread to him. Twenty-four hours after his fourth start – again against the Astros – the Dodgers had sold out for his next scheduled start.

Meanwhile, his start in New York drew nearly 20,000 more fans than the Mets’ average that season, and the number of radio stations carrying the Dodgers’ Spanish-language broadcasts skyrocketed. Reporters descended upon Etchohuaquila, eager to unspool the origin story of the young phenom.

Within a few short weeks, Fernandomania was sweeping the nation.

“I’ve never seen anything like it,” broadcaster Jaime Jarrín told Sports Illustrated. “We Latins are big sports fans. We’ve always had sports heroes, but they’ve been boxers. Fernando has the potential to become king of them all.”

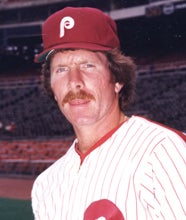

Valenzuela’s first loss came in his ninth start, a 4-0 defeat at the hands of the Phillies, sparked by Hall of Famer Mike Schmidt’s home run in the first inning.

“Maybe someday when he’s won his 39th Cy Young Award…maybe he’ll tell someone about it while I’m sitting here in my easy chair watching him,” Schmidt joked with reporters after the game.

The 1981 season came to a temporary close on June 12, due to a players’ strike which lasted through July 31, but neither Valenzuela nor the hordes of Fernandomania fanatics were flustered by the stoppage.

Valenzuela helped carry the Dodgers to the World Series title and became the first pitcher to win Rookie of the Year and the Cy Young Award in the same season.

“I’ve said it before, and I say it in measured tones, but the 1981 season and Fernandomania bordered on a religious experience,” recalled longtime Dodgers broadcaster Vin Scully. “I’ve seen great pitchers and cities who love players. But I have never seen anything like this, and I don’t think I will ever see it again.”

“When Fernando pitched, it wasn’t a sporting event, it was a social event,” echoed Jarrín, in a story from the Los Angeles Times. “All of a sudden, people wanted to learn Spanish and learn about Mexico. It was a wonderful way to bring two countries together.”

Valenzuela spent nine more seasons as member of the Dodgers rotation, but ultimately the distinctive screwball, coupled with heavy use early on in his career – from 1982-1987 he pitched at least 250 innings each season – proved to be his undoing, and the organization released him in 1991.

But for a man who earned the nickname “El Toro,” The Bull, his baseball career did not end there. He returned to Mexico in 1992 and pitched for the Jalisco Charros, going 10-9 with a 3.86 ERA. It was enough for the Baltimore Orioles to sign him as a free agent in 1993, where he went a respectable 8-10. Valenzuela again returned to the Charros in 1994, but was brought back to pitch for the Philadelphia Phillies at the end of the season and signed with the San Diego Padres the following spring.

The lefty spent two and a half seasons with his former division rival, including a 1996 campaign where he went 13-8 with a 3.62 ERA, before being traded and subsequently released. But his impact on the game still resonates today.

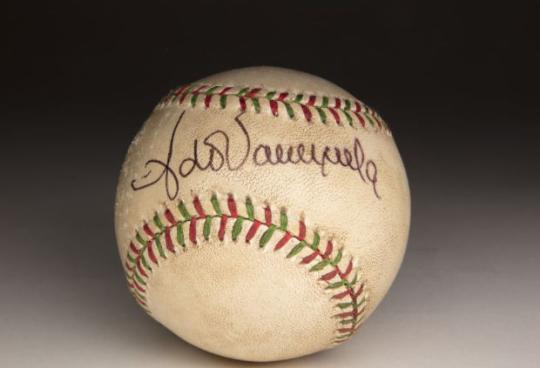

The collection at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum contains several Fernando Valenzuela artifacts, including a Dodgers jersey from his 1986 season when he led the National League with 21 victories and a signed ball from his June 29, 1990, no-hitter at Dodger Stadium.

“I truly believe that there is no other player in major league history who created more new fans than Fernando Valenzuela,” said Jarrín, in an interview for Dodger Magazine in 2006. “Sandy Koufax, Don Drysdale, Joe DiMaggio, even Babe Ruth did not. Fernando turned so many people from Mexico, Central America, South America into fans.”

Isabelle Minasian was the digital content specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum