- Home

- Our Stories

- Leyenda Mexicana: How Mel Almada shaped baseball history

Leyenda Mexicana: How Mel Almada shaped baseball history

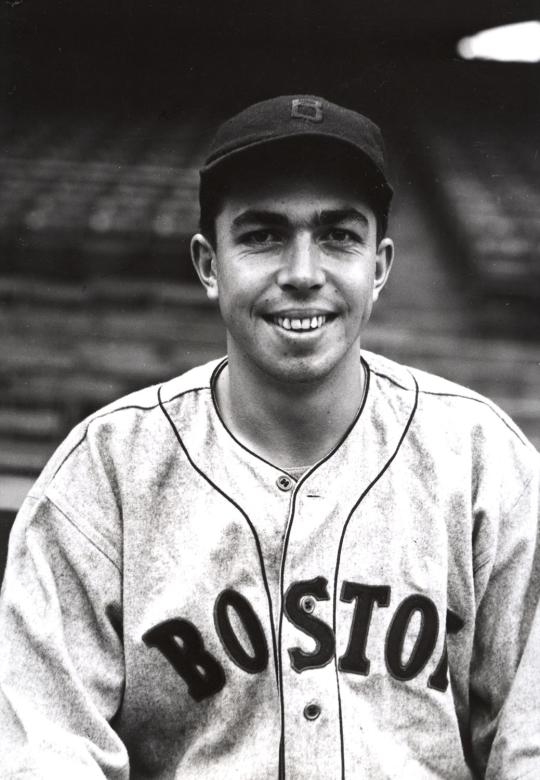

In 1933, Red Sox general manager Eddie Collins was in need of an infielder. He decided to make a trip to the West Coast, lured by scouting reports of a Seattle Indians second baseman named Freddie Muller.

With $40,000 from owner Tom Yawkey and an expectation of two player-signings, Collins would purchase Muller later that year. He played only 17 games for the team, serving as a utility man but struggling at the plate. Mel Almada, on the other hand, was another story.

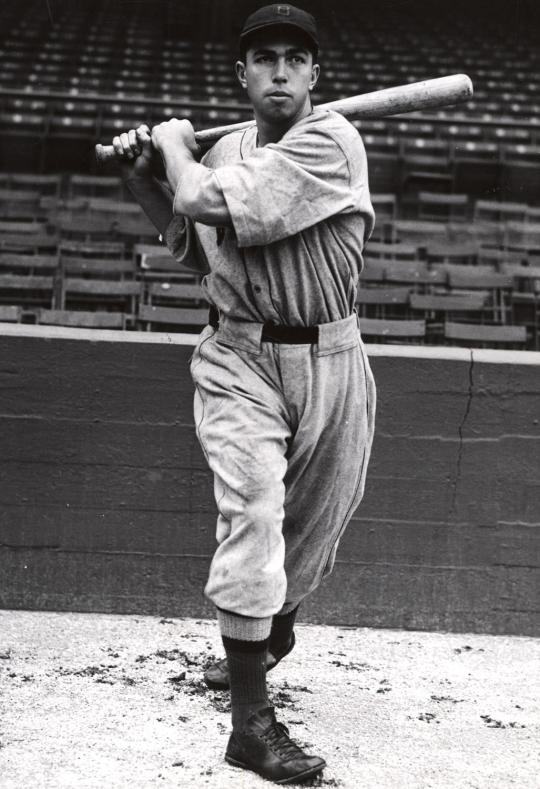

Baldomero Melo Almada Quirós was born in Huatabampo, Mexico, in 1913. He was the great-great grandson of Don José María Almada, a powerful patriarch who owned Mexico’s largest silver mine, La Quintara. His family legacy was intertwined with Mexican folklore, as tales of Don José María’s extravagance spread like wildfire throughout the Sonora region.

But with the onset of the Mexican Revolution, everything changed for the Almada family. Amid the chaos, Mel’s father, Baldomero Almada Sr., was appointed governor of Baja California by the then-President at the time, Álvaro Obregón. The incumbent governor resisted, and rather than fight back, Almada asked to be appointed to the Mexican consulate in Los Angeles.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

“My father always wanted us children to have an American education,” Mel said to the Sporting News. “So when the opportunity came along for him to become Mexican consul at Los Angeles, he turned over most of his property to relatives and moved us all to this country. I was then only a year and one-half-old, so, you see, I am very much an American.”

It didn’t take long for Almada to realize that he was a gifted athlete. Earning letters in football, baseball and track throughout high school, he set a southern California record for the long jump at 23-4¾. After his older brother Lou began playing with the Seattle Indians, Mel signed with the team in 1932, unsure of what position he would play. Manager George Burns put him in right field, where he posted a fielding percentage over .900.

By the time Collins made it out to Indians’ camp in 1933, Almada was putting up numbers that the Red Sox simply couldn’t ignore. A solid contact hitter, he averaged .311 in his rookie year with the Indians, following that up with 204 hits and a .323 average, not to mention sharp defense and blistering speed on the base paths.

“You have a good prospect in that young fellow Almada,” Collins said to the team. “And if you want to get him in the big show I will buy him, too. He looks fast and shapes up like a hitter.”

Debuting at Fenway Park on Sept. 8 in a doubleheader, Almada’s cup of coffee ended in the “L” column, as the Red Sox lost both games to Detroit, 4-3. But just as Collins had taken note in Seattle, the New England papers didn’t miss the bigger story.

“Work of Almada a Bright Spot in Red Sox double loss” the Boston Globe proclaimed on Sept. 9, after the rookie recorded a walk and two hits in his first games up:

“About the only consolation the crowd got out of the game was the good work by Almada, a new outfielder, who showed up wonderfully well in his first appearance as a big leaguer,” the Globe wrote. “He made a hit in each game and two marvelous catches in the outfield and altogether, made a wonderful showing.”

Evoking comparisons to Tris Speaker for his defense, Almada could also produce at the plate, finishing his abbreviated first season at .341. Collier’s magazine ran a three page feature story on the rookie, proclaiming him “Mexico’s extraordinary ambassador to baseball”:

“The thumbnail sketch of his genealogy was deliberately prefixed because not only is he the first real Mexican ever to crash the majors and stick, but because also it’s doubtful if any player in the history of the national pastime ever brought the game a prouder or more picturesque personal background.”

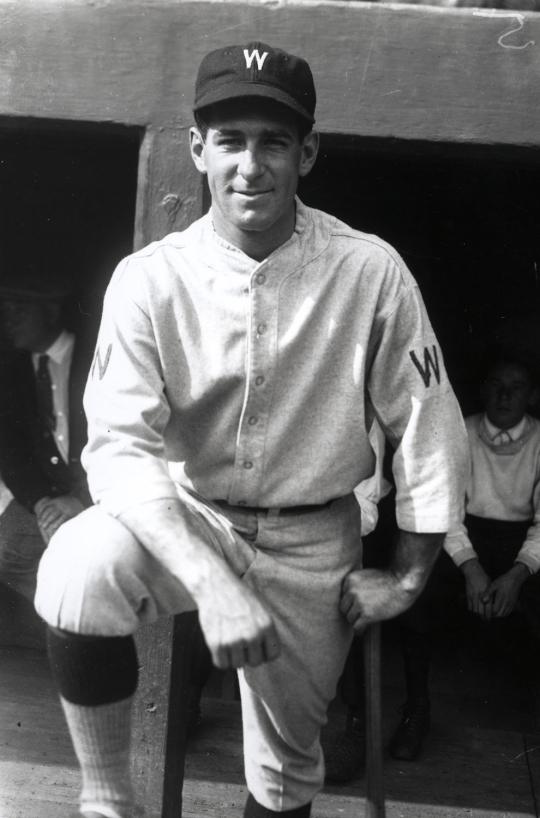

After 5 seasons in Boston, Almada was traded to the Washington Senators in 1937, as part of a five-man trade. Despite his strong start with Boston, it was in Washington where he felt he improved his hitting the most, crediting future Hall of Fame and then-Senators manager Bucky Harris for his production at the plate:

“Bucky told me I was a natural-born hitter,” he said to the Los Angeles Times. “And that I could go to town if I used a heavier bat -- thirty-five ounce instead of thirty-three -- and change my stance and wait for the good ones.”

Whatever Almada changed paid off, as he recorded a 29-game hitting streak the following season with the St. Louis Browns. According to SABR, it was the third longest by a Hispanic major league player in the 20th century.

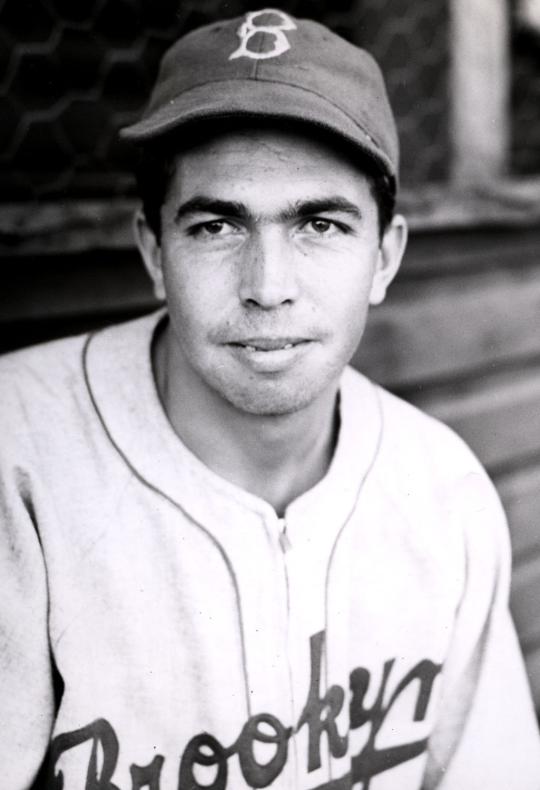

After one more season with the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1939, Almada left the major leagues, playing with the Triple A-Sacramento Solons in 1940 and managing in the Mexican League for the next decade, while taking time off to serve in World War II from 1944-45.

He was inducted into El Salón de la Fama del Beisbol Profesional de México in 1971, but had always served as an icon for Mexican ballplayers with dreams of making it to the show. Nearly 50 years after Almada’s debut, Fernando Valenzuela exploded onto the baseball scene with the same fervor as his predecessor.

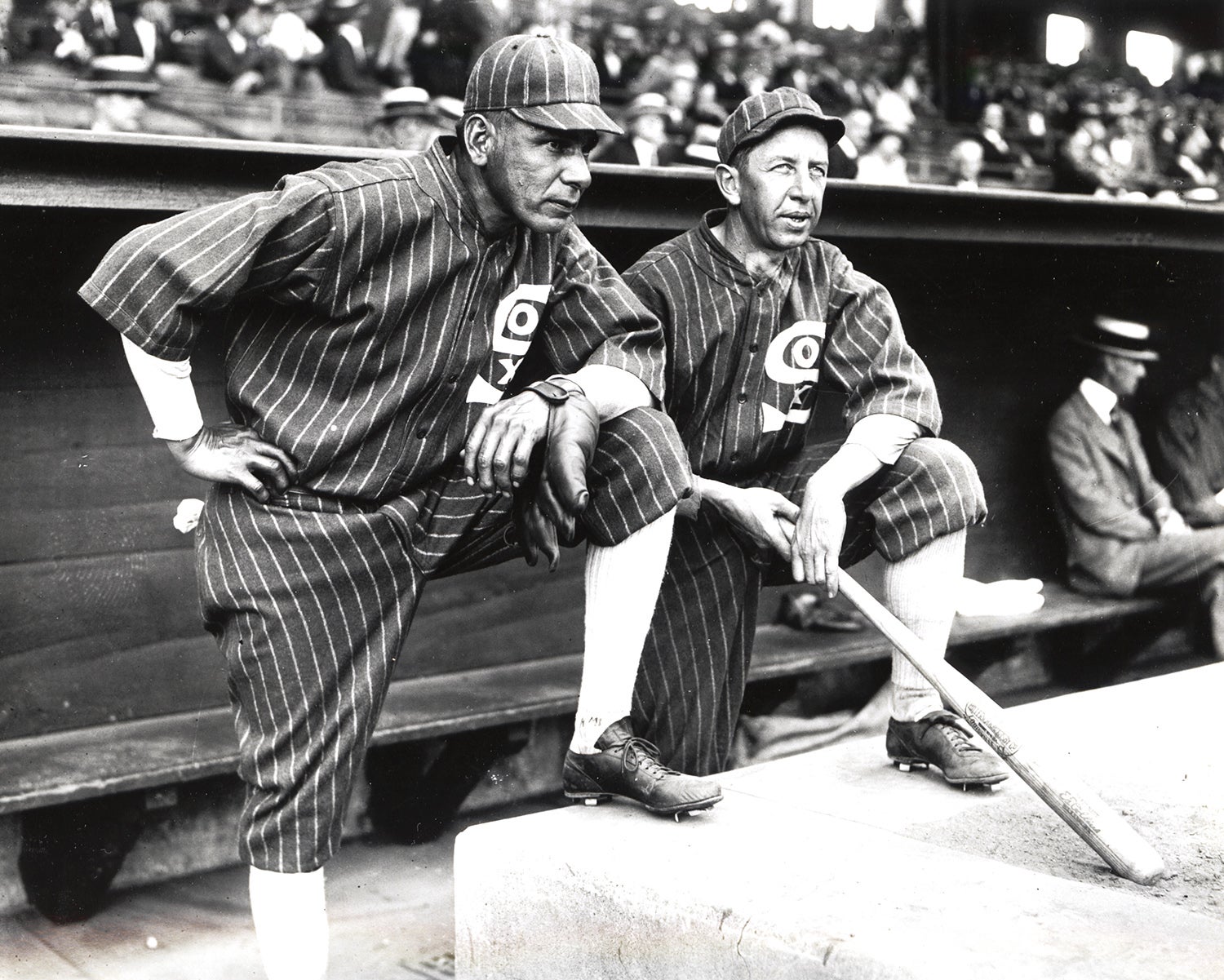

Bucky Harris, manager of the Washingon Senators, helped outfielder Mel Almada improve his hitting mechanics during Almada’s time with the team in 1937 and 1938. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

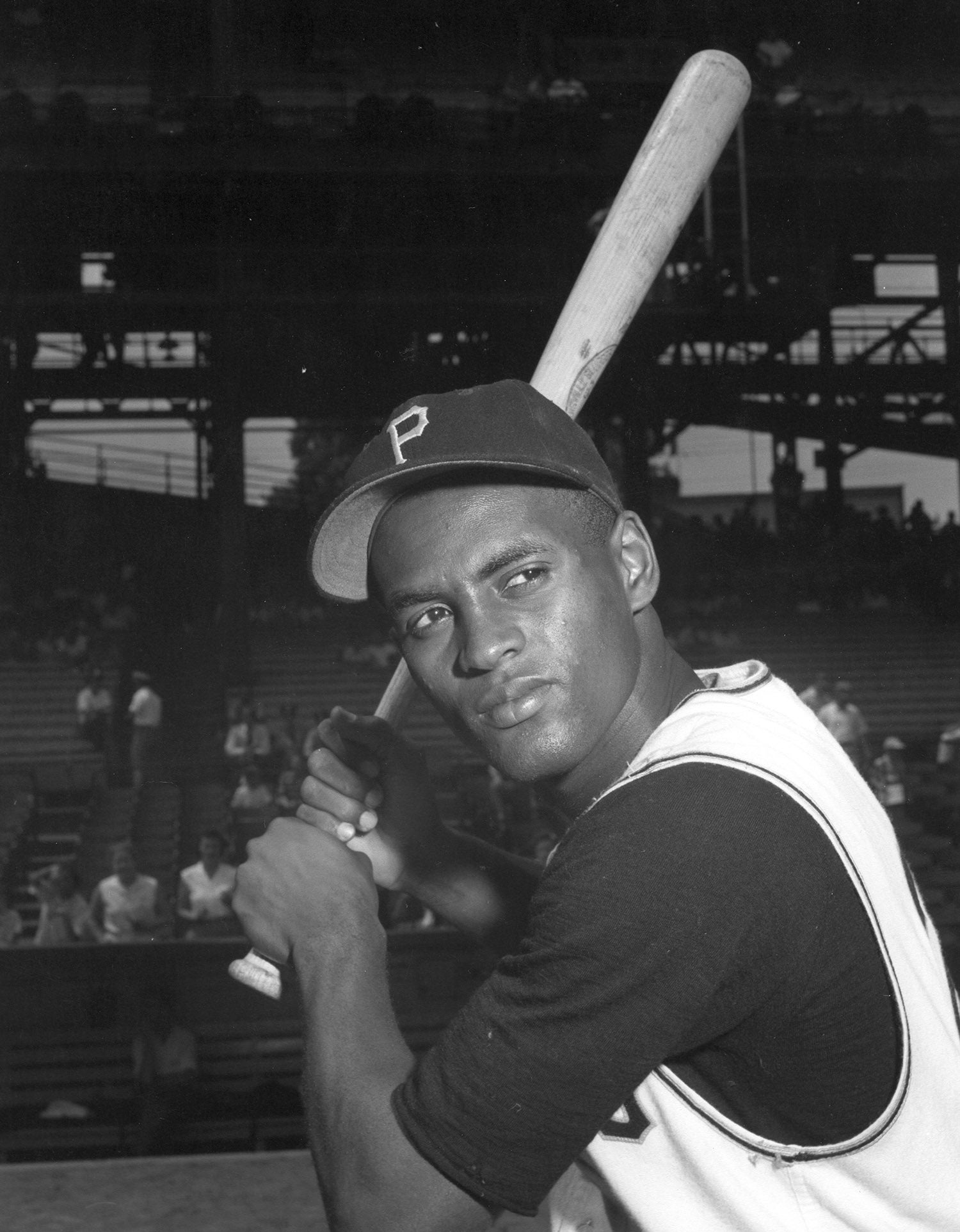

Mel Almada finished his career with the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1939, before moving to the minor leagues to play with the Triple-A Sacramento Solons. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

“I said once to a bunch of reporters in Navojoa that someday we were going to see a boy from one of those ejidos make it in the major leagues. They laughed at me,” Almada said to the Arizona Daily Star. “But here he is. And he’s the best thing that could happen to the sports world. Sports is a morale booster. Kids idolize him – and kids need idols.”

Since Almada’s debut, more than 125 Mexican players have made it to the big leagues. The country continues to develop as a breeding ground for baseball talent, carrying on the legacy of the Ortas, Valenzuelas, Avilas – and, of course – the Almadas.

“Look at this. We have a hero in the United States and he can’t even speak English,” Almada said about Valenzuela, who would win the National League Rookie of the Year and Cy Young Award in 1981. “There are lots of Mexicans who could have played in the big leagues but didn’t want to because they didn’t like the culture. It’s this type of success that will bring more of them in.”

Alex Coffey was the communications specialist at the Baseball Hall of Fame