- Home

- Our Stories

- Gamble’s bat, good humor and hair made him an icon of the 1970s

Gamble’s bat, good humor and hair made him an icon of the 1970s

Oscar Gamble was not a Hall of Famer. Except for one season, he was not regarded as a star. For much of his career, he was not even an everyday player.

But Gamble was a very good role player who lasted a long time in the major leagues. And in many ways, his career reflected the era of baseball in the 1960s, 70s and 80s. He was a player who dealt with some of the most prominent racial, social and cultural issues of the day. One could argue that Oscar Gamble was a signpost for the game in the expansion era.

Born and raised in rural Alabama, Gamble lost his father, Sam, when he was only six. His mother, Mamie, then moved the family to the city, where she took on work as a maid and as a factory worker. One day she was struck by lightning, which she survived, but left her unable to work. Oscar’s brothers picked up the slack by taking jobs in a local meat processing plant.

Not only did the Gambles struggle financially, but they also had to endure the experience of Jim Crow segregation that was so prominent during the decades of the 1950s and 60s, particularly in southern states like Alabama. To make matters worse for Oscar, his athletic opportunities were limited because his high school, George Washington Carver High, did not have a baseball team. Unable to play scholastic baseball, Oscar joined a semi-pro team that was managed by his brother, Jimmy.

It was while playing for that semi-pro team, the Oakwood Clowns, that Oscar’s life changed one day in 1968. That’s when he met Buck O’Neil, the former Negro Leagues player and manager who had become a coach and a scout with the Chicago Cubs. O’Neil spotted Gamble playing for the Clowns on a remote field near Montgomery.

Prior to that day, no big league club had even heard of Oscar Gamble. As an amateur ballplayer, he was hardly considered a top prospect. At 5-foot-11 and 160 pounds, he looked more like a batboy than a ballplayer. But once O’Neil witnessed Gamble’s remarkable bat speed, he became interested in the young left-handed hitter, who reminded him of Billy Williams. After the game that day, O’Neil talked to Gamble and came away impressed – fully convinced that the Cubs should draft and sign him.

Listening to O’Neil’s advice, the Cubs picked Gamble in the 16th round of the 1968 MLB Draft. Having already established a relationship with Gamble, O’Neil managed to sign him to a contract within two weeks. O’Neil told anyone who would listen that Gamble was the best prospect he had signed outside of the great Ernie Banks.

The Cubs assigned the 18-year-old Gamble to their Rookie League affiliate in Caldwell, Idaho. Limited by a leg injury that summer, he put up mediocre numbers for Caldwell, but impressed his manager, George Freese, with his swing and athletic nature. The Cubs thought enough of Gamble to invite him to Spring Training in 1969. He received extra playing time because of an injury to the Cubs’ regular center fielder, Adolfo Phillips, and drew the attention of Cubs manager Leo Durocher.

“Gamble reminds me of Willie [Mays] when he was breaking in. I know it sounds wild, but this kid compares with Willie when Willie was first coming up,” Durocher told the Sporting News.

Gamble must have been flattered by that comparison, since Mays was one of his boyhood heroes, along with Hank Aaron. Durocher also raved about Gamble’s upbeat attitude, noting that the youngster always seemed to be smiling.

With Durocher fully in his corner, the Cubs considered the possibility of putting Gamble on their Opening Day roster, but then decided to take a more conservative approach. Even so, they assigned him to their Double-A affiliate at San Antonio, a major jump up from his Rookie League stop in 1968. Gamble played well for San Antonio and then received a call to Chicago when Jimmy Qualls went down with an injury in August.

It was a classic case of rushing a player to the major leagues. At 19, Gamble was too young and not ready to hit major league pitching. He was also miscast as a center fielder, where he had trouble reading balls off the bat.

Just that quickly, the Cubs soured on Gamble. That winter, the Cubs began to shop Gamble in trade talks. They soon agreed to a deal, sending Gamble and hard-throwing reliever Dick Selma to the Philadelphia Phillies for 30-year-old Johnny Callison.

The trade came as a surprise to some in Chicago, but there appeared to be more than Gamble’s ill-fated major league debut factoring into the decision. According to a story in the Chicago Sun-Times, some members of Cubs ownership became upset when they learned that Gamble had dated white women. Even though 22 years had passed since Jackie Robinson integrated the National League, some of the game’s old guard conservatives remained stuck in the past with regard to social customs. They considered Gamble’s personal life unacceptable.

On the surface, Philadelphia seemed like an odd destination for Gamble, given its history of deep racial tensions. But an early problem that developed in Philadelphia seemed to have little to do with race. The Phillies cut Gamble from the major league roster during Spring Training, sending him to their minor league camp. That decision angered Gamble, who felt that he belonged with the Phillies.

“I’d rather sit on the bench in the majors than play in the minor leagues,” Gamble told Philadelphia sportswriter Ray Kelly. Upset by the move, Gamble left the Phillies’ spring camp entirely.

After a few days, Gamble thought better of his decision and returned to Spring Training. The Phillies assigned him to the Eugene Emeralds, their Triple-A affiliate in the Pacific Coast League. He played well for the Emeralds, before earning a promotion to Philadelphia in the middle of May, replacing a slumping Larry Hisle.

The racial atmosphere that existed in Philadelphia did not seem to affect Gamble. The problem he faced had to do with how the Phillies viewed him as a player. They wanted him to play center field. They also wanted him to adopt a slap-hitting approach at the plate. The plan did not work; Gamble played poorly in center field, while hitting a mediocre .262 with no power. One of the few highlights of his 1970 season came on the final day, when he drove in the winning run with a single, the last hit in the history of Connie Mack Stadium.

Gamble played three seasons with the Phillies, but did not develop. After the 1972 season, the Phillies gave up on Gamble, sending him and minor league slugger Roger Freed to the Cleveland Indians for veteran center fielder Del Unser. During his first Spring Training with the Indians, he worked with his new batting coach, Rocky Colavito. The former Indians star changed Gamble’s batting stance, convincing him to hit out of a deep crouch. Colavito also encouraged him to open up his stance to allow him to look more directly at the pitcher.

Colavito’s suggestions worked. In 1973, Gamble batted .267, a major improvement over his days in Philly and Chicago. He also developed more patience at the plate, resulting in more walks and fewer strikeouts. With the Indians, the lefty-swinging Gamble played almost exclusively against right-handed pitching, to the point that he began to establish a reputation as a platoon player. It was a label that would remain with him for the rest of his career.

Off the field in Cleveland, Gamble developed a business interest that reflected the changing times. In 1976, he would open up a disco, reflecting the new kind of music that was becoming fashionable. Fitting in with the look and aura of the disco scene, Gamble made some bold fashion and grooming choices. While commuting to and from the ballpark, he wore outfits that included plaid pants and a pair of gaudy elevator shoes.

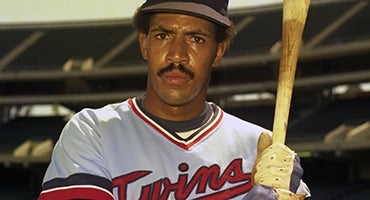

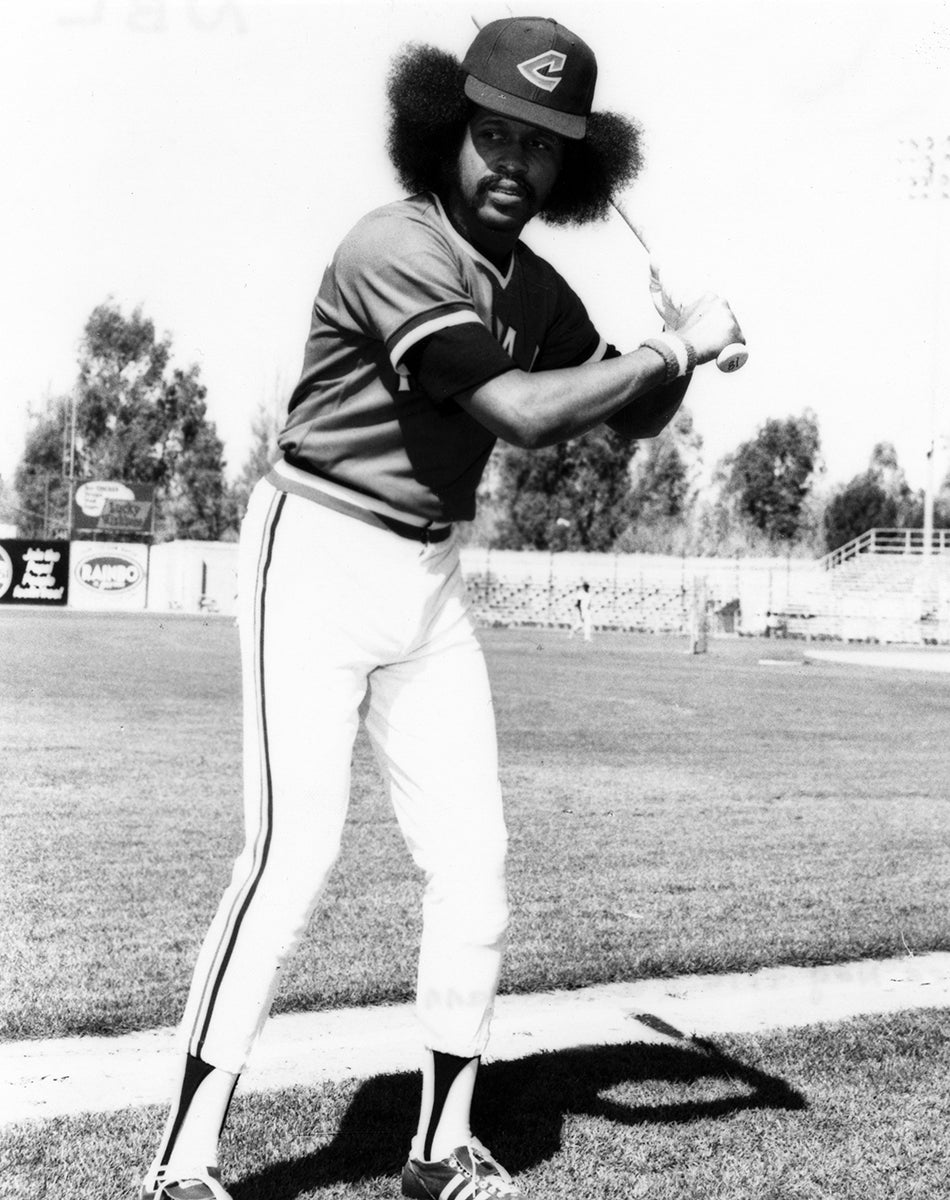

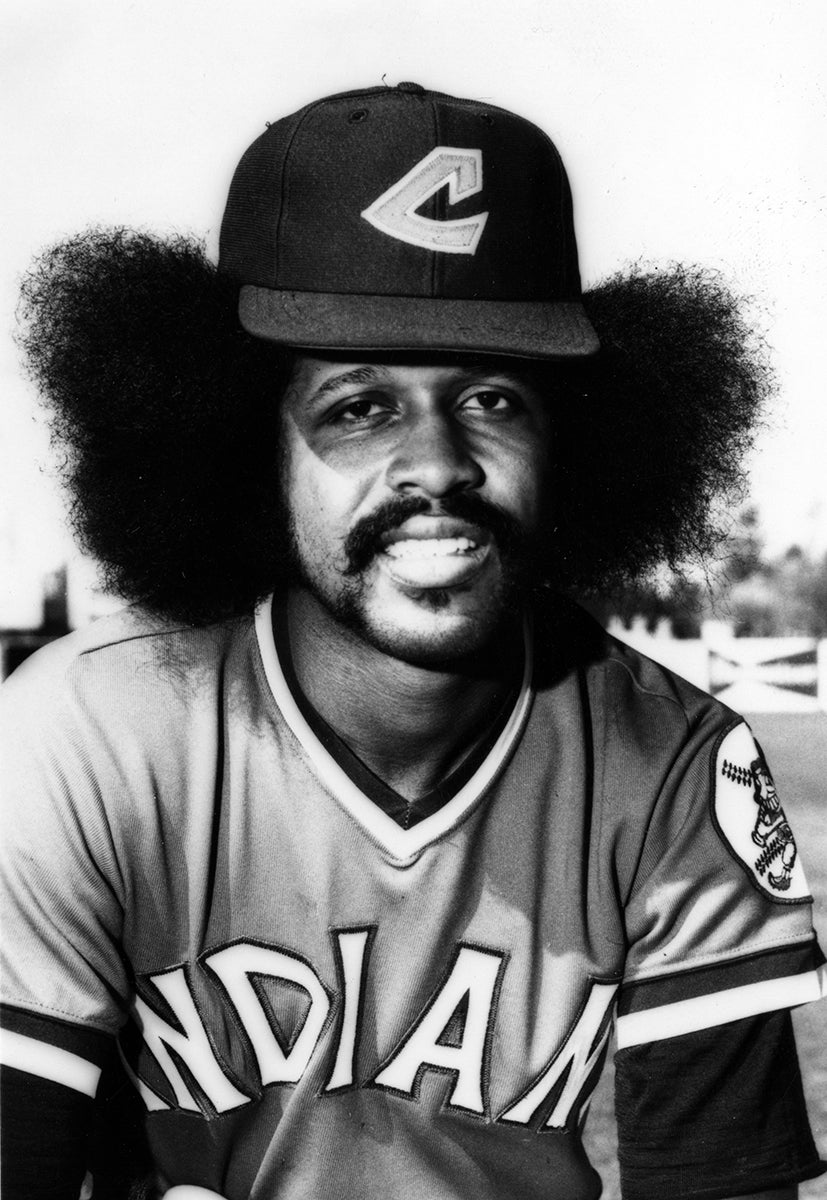

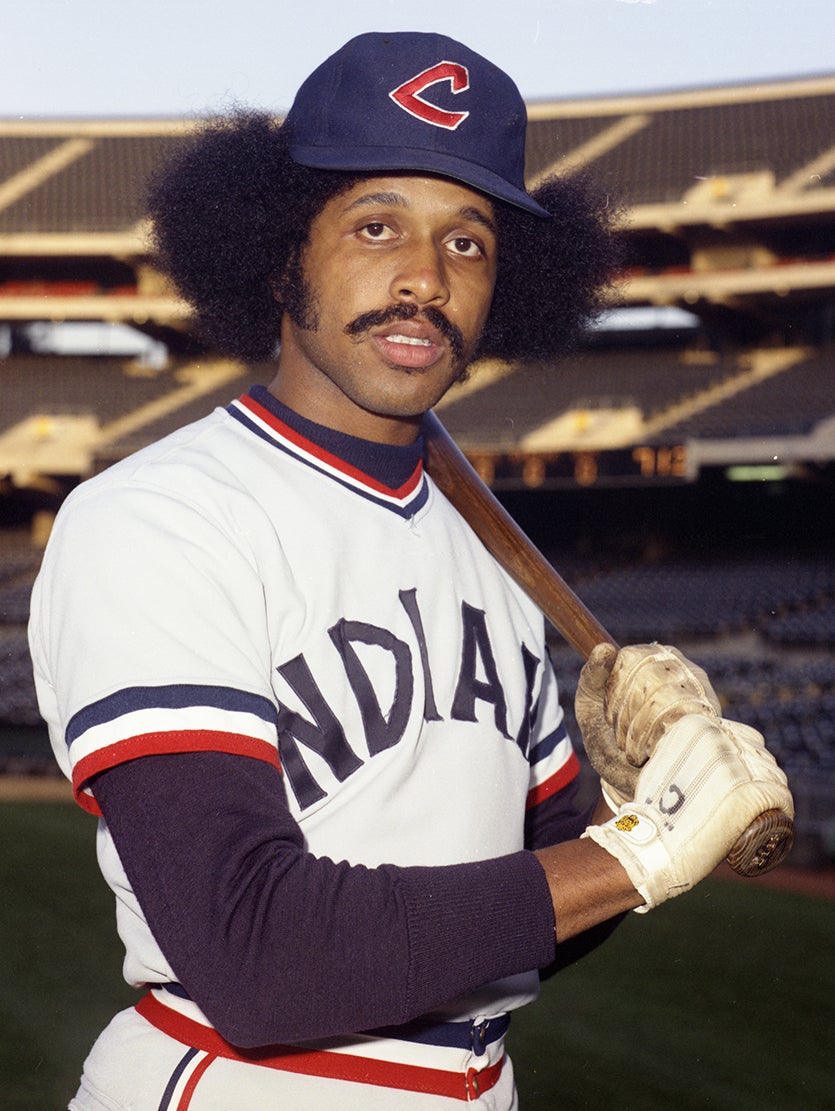

Just as significantly, Gamble began to grow out his hair out in Cleveland. He had reported to his first Spring Training with the Indians sporting a full Afro, which did not please manager Ken Aspromonte, who “suggested” that he trim his hair. Gamble complied, but then allowed his Afro to grow out gradually during the season. Gamble’s Afro would eventually become one of the largest in all of baseball, a sport that had been known for longstanding conservative hair styles but had just seen the Oakland A’s buck a decades-long trend of clean-shaven faces by sporting mustaches in 1972.

In 1974, Gamble reported to the Indians’ spring camp wearing what the Associated Press called “the wildest Afro hairdo in camp.” Gamble’s Afro was so large that it measured four inches in length on the top while puffing out on both sides of his cap and helmet. When Gamble ran the bases or chased down fly balls in the outfield, his helmet and cap often fell off his head, unable to withstand the pressure of his large head of hair.

The photographs on Gamble’s 1975 and 1976 Topps cards certainly reflect his distinctive hairstyle. (His 1976 Topps Traded card remains a cult classic among collectors.) Gamble regularly received those cards in the mail, with requests from fans to sign the cards and return them. (That trend would continue long after his retirement from the game.) While Gamble had grown the largest Afro in the major leagues, there was one professional athlete who appeared to have outdone him. Darnell Hillman, a power forward with the Indiana Pacers of the American Basketball Association, sported an Afro that somehow seemed larger than Gamble’s.

For most fans of the game, Gamble’s Afro became an offbeat and fun topic of conversation. But there were some fans who taunted Gamble, yelling insults his way and telling him to cut his hair. Additionally, some members of the media believed that Gamble’s hairstyle was a clear sign of Black militancy.

“There were some sportswriters who wouldn’t even talk to me,” Gamble told the Sporting News in 1979. “They thought I was some kind of militant with my beard and my hair.”

For his part, Gamble denied that he was a radical or an extremist trying to make a political statement. Gamble explained that he had first grown his hair out simply because he was a young player looking to be noticed.

Gamble became a popular player with the Indians, and later with the New York Yankees and Chicago White Sox, but his large Afro attracted criticism of a racist nature. Some within the game pointed to his Afro as a sign that he was a troublemaker, an accusation that lacked any merit.

“I liked [the hair], but I guess it did cause me to get a bad reputation,” Gamble told the Sporting News. “People took one look at that hair and thought I was a bad guy.”

Some critics implied that Gamble was a loafer who didn’t always play hard, even though they couldn’t point out any real evidence behind the claim. Gamble certainly regarded the criticism as unfair, tracing it back to his hairstyle. In truth, Gamble had good relationships with most of his managers, none of whom publicly took him to task for a lack of hustle. One of his managers in Cleveland, Frank Robinson, became upset when Gamble complained about his continuing role as a platoon player, but the fractious relationship did not stem from any lack of effort or work ethic.

For their part, the Indians did not seem to mind Gamble’s hair, but his next team did – if only because it violated team rules. During the winter of 1975, the Yankees acquired Gamble for right-handed pitcher Pat Dobson. For years, the Yankees had operated under a strict policy forbidding not only beards and long sideburns, but also long hair and large Afros. When Gamble reported to the Yankees’ Spring Training camp in 1976, he discovered that there was no uniform in his locker. His manager, Billy Martin, told Gamble that Yankees owner George Steinbrenner would not issue him a uniform until he cut his hair. Gamble complied willingly.

Still, the rule created a bit of a predicament. Gamble had arrived at Yankees camp on a Sunday when all of the barbershops in Ft. Lauderdale, Fla., were closed. Yankees public relations director Marty Appel, always creative in finding a solution, contacted a local barber and arranged for him to come in on his day off and cut Gamble’s hair to conform to the Yankees’ legal limit. Paying the barber extra for his special Sunday effort, the Yankees forked over $35 at a time when most haircuts went for less than $10.

Gamble took well to New York, where the media came to appreciate his willingness to talk and his creativity in turning a phrase. On the field, Gamble’s uppercut pull swing became a natural for the dimensions of Yankee Stadium. He played well for the Yankees in 1976, but his New York City stay lasted just the one season. The team’s signing of Reggie Jackson made Gamble expendable. Just before the start of the 1977 season, the Yankees traded Gamble and two minor league prospects to the White Sox for a young shortstop named Bucky Dent.

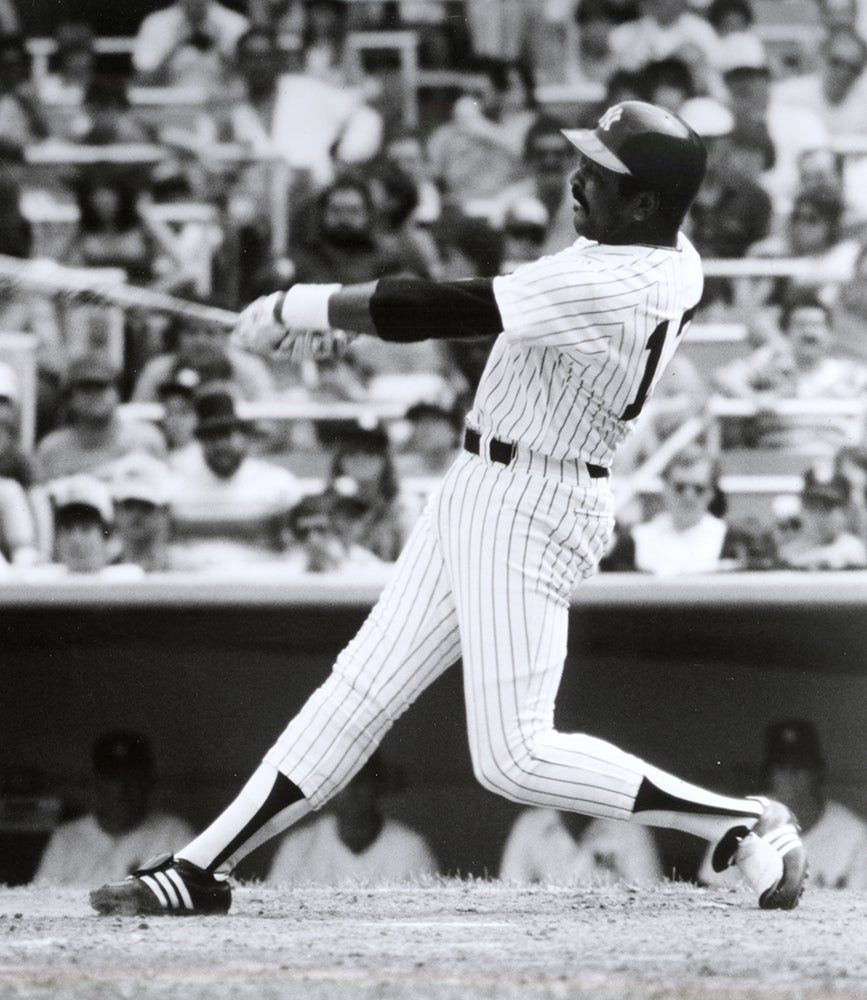

The trade would turn out to be a boon for both the White Sox and Gamble. Although he occasionally sat on the bench against left-handers, he played in 137 games, the most of his career. Hitting 31 home runs and slugging a remarkable .588, he became an integral part of a fabled White Sox team known as the “South Side Hit Men.” Gamble became so popular that he developed something of a cult following in Chicago.

In a perfect world, Gamble would have remained with the White Sox for years. But he was now a free agent in baseball’s new economic system. Sox owner Bill Veeck did not have the financial resources to sign him to the kind of long-term contract that a young, power-hitting outfielder could command.

To the disappointment of White Sox fans, Gamble signed with the San Diego Padres, earning an astonishing six-year contract worth $2.85 million. While Gamble made out well financially, it turned out to be a bad fit in terms of his playing career. San Diego’s Jack Murphy Stadium did not play well for a pull-hitting slugger like Gamble. Appearing in 127 games, he hit only seven home runs and slugged a paltry .387. The Padres were so disappointed that they traded Gamble after just one season, sending him to the Texas Rangers as part of a deal for first baseman Mike Hargrove.

As he did in his other major league stops, Gamble provided an upbeat and outgoing personality that made him a good fit in the Texas clubhouse. He played with the Rangers for most of 1979, hitting .335 as a highly productive platoon DH. Somewhat strangely, the Rangers traded him late in the season, sending him to the Yankees as part of a package for Mickey Rivers.

For the next five seasons, Gamble served as a part-time right fielder and DH for the Yankees, where he was especially suited for a stadium with small dimensions to right field. On a team brimming with controversial figures and clashing personalities, Gamble provided an oasis of calm. He also proved quotable for the New York press. As he once said in response to how controversies always engulfed the Yankees: “They don’t think it be like it is, but it do.”

In the spring of 1982, Gamble found a bit of controversy himself when he invoked his no-trade clause, vetoing a trade that would have sent him, first baseman Bob Watson, and right-hander Mike Morgan to the Texas Rangers for star DH and first baseman Al Oliver. Gamble did not want to return to the Rangers because he was still upset with the team’s general manager, who had traded him in 1979 without telling him face-to-face.

Steinbrenner did not forgive Gamble for the veto and purportedly ordered Billy Martin to use him as little as possible. Martin ignored the order, using Gamble as he normally would have. Gamble had a good season, clubbing 18 home runs with a .522 slugging percentage. He even batted well against lefties, to the tune of a .382 batting average.

Over the next two seasons, Gamble’s playing time dwindled as his bat slowed. Becoming a free agent after the 1984 season, Gamble signed with the White Sox for what turned out to be his major league swansong. He didn’t hit much but did manage to hit his 200th career home run.

After his playing days, Gamble opened up a sporting goods store in Montgomery. He later worked as a youth baseball instructor and spent some time as a sports agent. Ironically, as he grew older, he lost most of his hair, which motivated him to shave his head.

In his last few years, Gamble developed a rare tumor of the jaw. The disease took his life in 2018. He was just 68.

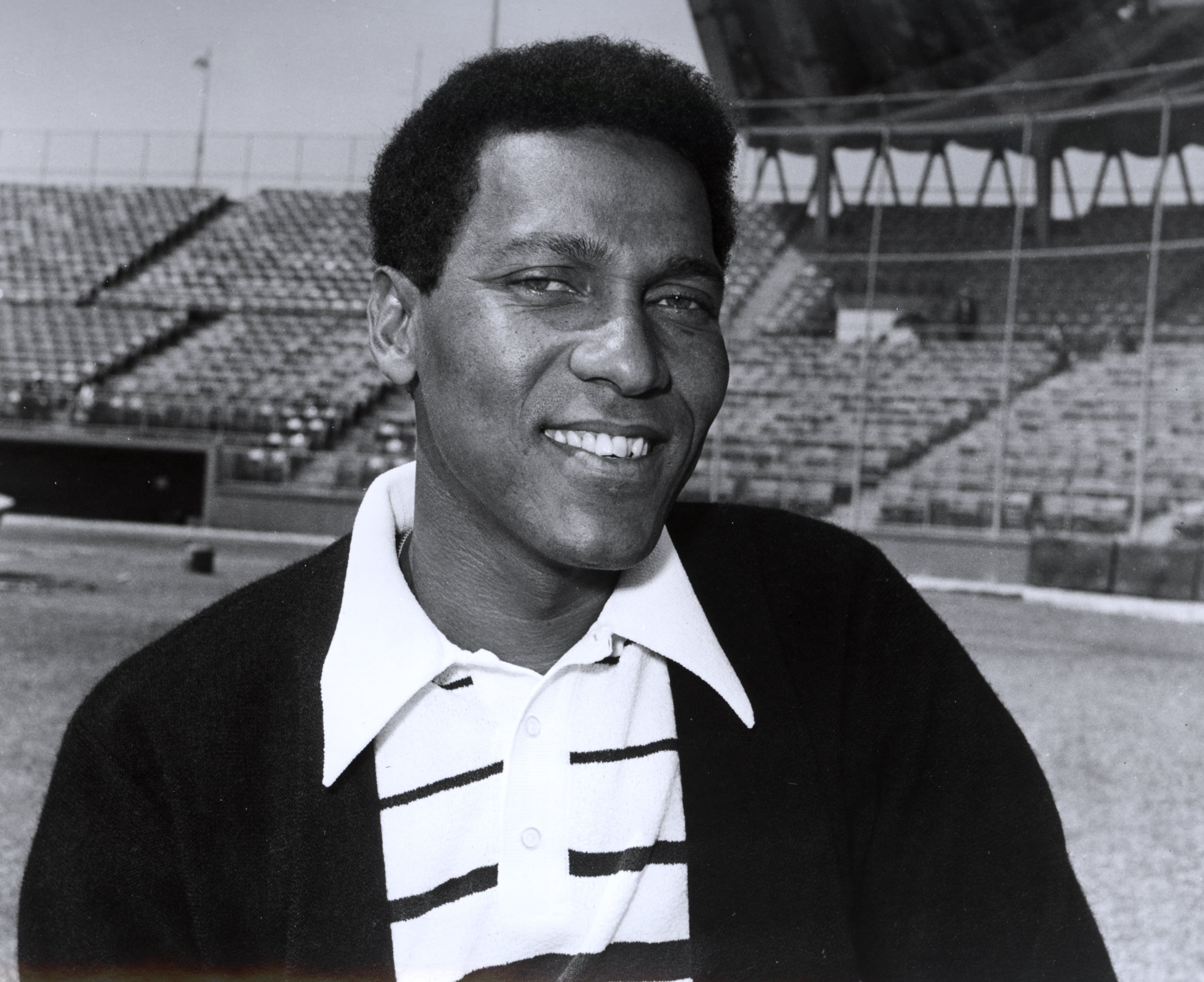

Ordinarily, the death of a role player might receive little attention. But Gamble’s passing drew a strong reaction from fans and fellow players. He was well-remembered, from the story of being signed by Buck O’Neil, to his outlandish clothes, to that iconic Afro. But perhaps more than anything, he was remembered for his personality, his attitude, and his humor.

“Oh my God, he was hilarious, great sense of humor, just very close to all of us,” Hall of Famer Goose Gossage told the New York Daily News. “I played on nine different teams and had a lot of teammates, but they didn’t come any better than Oscar Gamble.”

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum