- Home

- Our Stories

- Lucas broke barriers in Braves’ front office

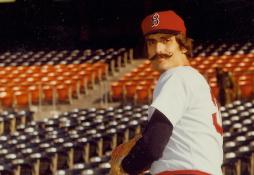

Lucas broke barriers in Braves’ front office

Some figures in baseball history tend to be overlooked. For players, it can happen because they played in small markets or never had a chance to perform on the grand stage of the World Series. For managers and front office personnel, it can occur because of introverted personalities and a lack of interest in self-promotion.

Then there are tragedies. Some people within the game have left us so quickly that it becomes too easy to forget their considerable accomplishments. That’s exactly the case for one such person who worked in a team’s front office, did good work, and was then taken from us before most had a chance to take notice.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

STORIES OF BLACK BASEBALL

Stories that highlight the lives and experiences of Black ballplayers through key moments in history, artifacts and baseball cards.

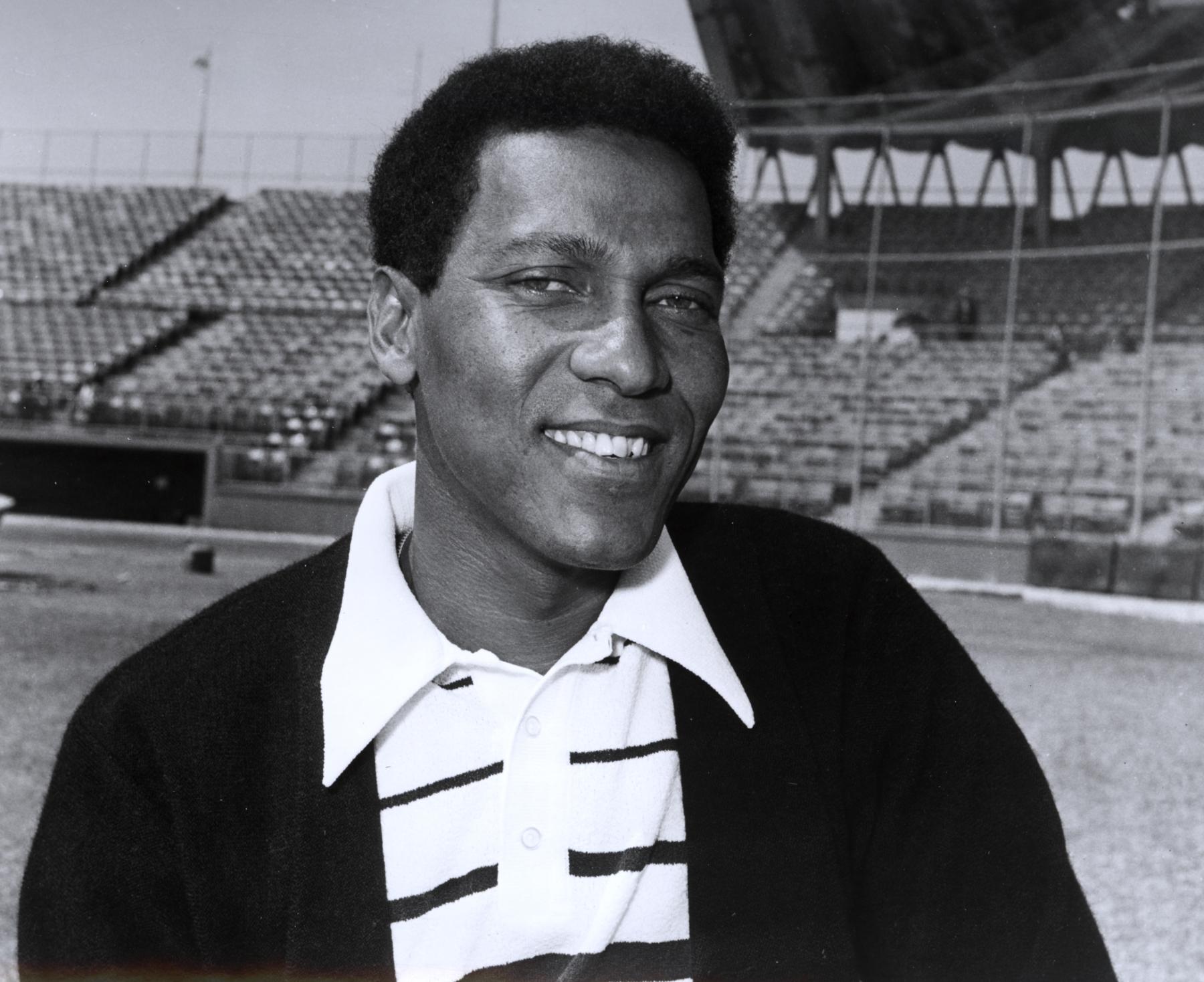

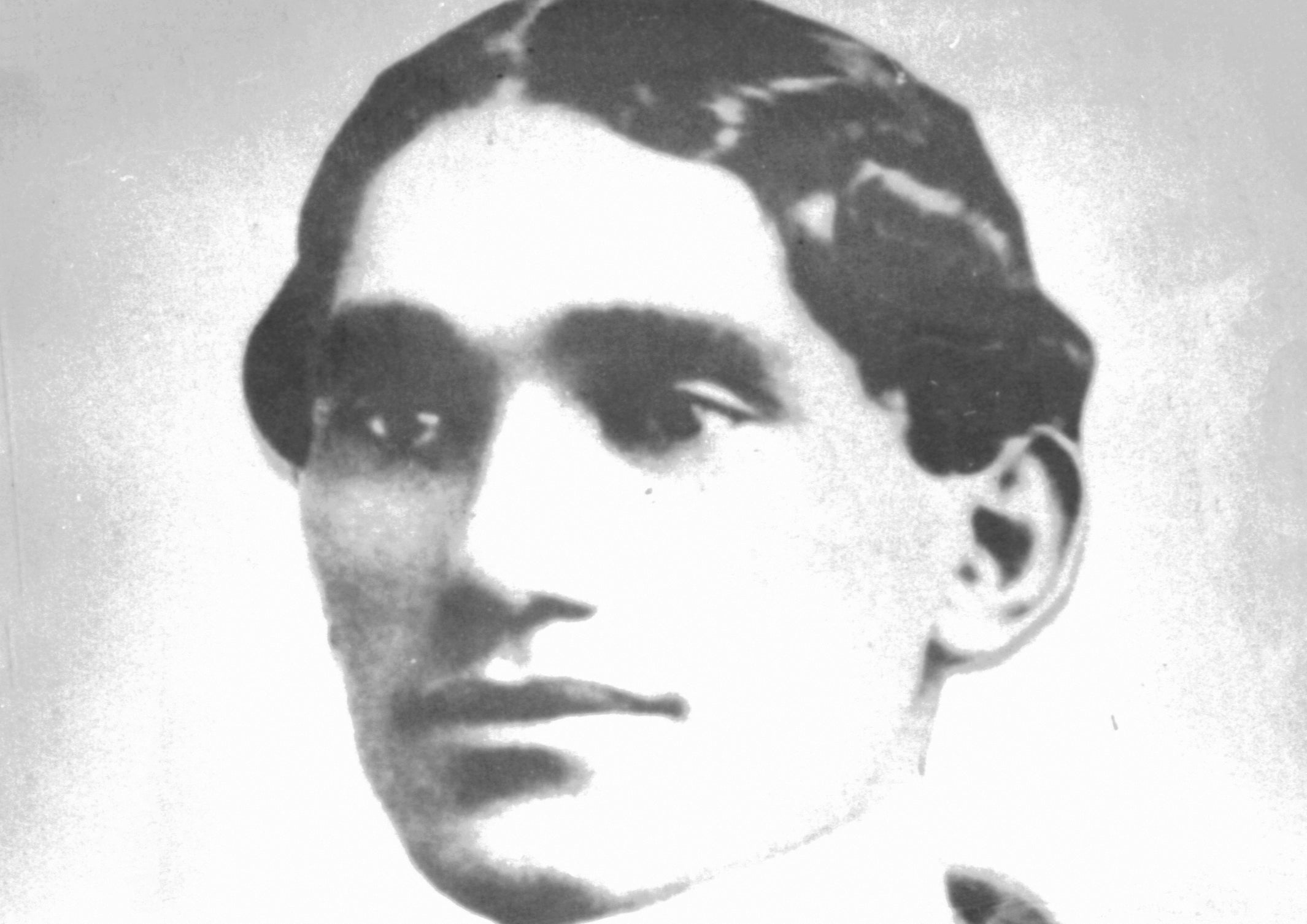

Bill Lucas is not a household name, at least not to most fans outside of the Atlanta area. A graduate of Florida A & M in the mid-1950s, the young infielder signed a contract with the Milwaukee Braves in 1957. After one season, his minor league career was interrupted by a two-year stint in the U.S. Army, but he returned to the Braves’ system in 1960.

As a minor league player, Lucas faced the kind of racism that plagued most Black players of the era. One of his teammates was Paul Snyder, who would later work under Lucas as a scout with the Braves. Snyder recalled the Jim Crow segregation that placed so many restrictions on Lucas, particularly during his four years in the Texas League.

“A number of places in the Texas League, where we were playing in 1962, Luc couldn’t sleep in the same hotel we did,” Snyder once told Atlanta Magazine. “He couldn’t eat in the same place we did. A lot of nights, we’d bring food down to him in the bus. A lot of nights, he’d sleep in a boarded-up hotel downtown. He just buttoned his lip, went out and played his heart out.”

A good contact hitter who ran well and played second base, shortstop and third base, Lucas made it as high as Triple-A ball. But a knee injury suffered in Double-A contributed to the end of his six-year playing career in 1963 and prevented him from fulfilling his dream of playing in the major leagues.

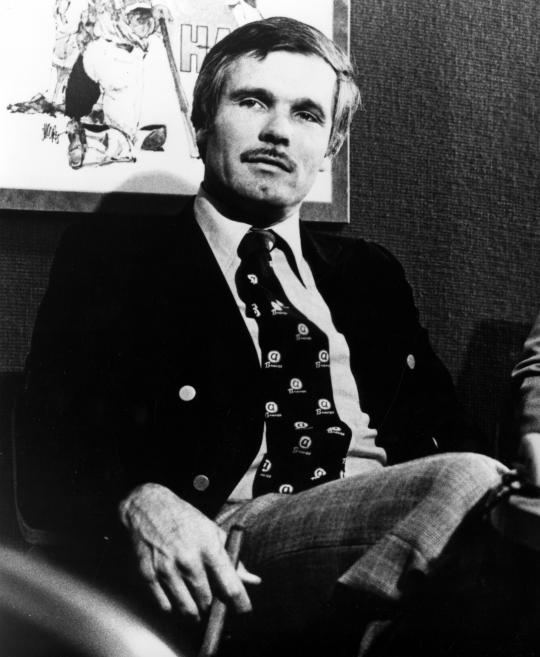

While Lucas fell short of that goal, his intelligence, work ethic and personality so impressed the Braves that they hired him in 1965, giving him a job in their promotions and sales department. By 1967 (with the Braves now in Atlanta), the organization realized that Lucas’ talents would best be served in player development. Lucas made a smooth transition to that area, working his way up the ladder to become director of the Braves’ farm system by 1972.

In 1976, businessman Ted Turner purchased the Braves and quickly grew to like Lucas. With the Braves mired in last place and some 30 games out of first place in mid-September, Turner decided to make a change.

He promoted Lucas to vice president of player personnel. In essence, Turner made Lucas the team’s general manager, giving him ultimate responsibility for all player transactions. The official job title did not recognize the significance of the moment, but Lucas essentially became the first Black general manager in the history of either the National or American Leagues.

The historic hiring also culminated a steady but remarkable climb for Lucas – from career minor leaguer to general manager in 11 years.

In an interview with The Atlantic, Lucas’ widow Rubye revealed that her husband initially bristled at the attention given to his status as baseball’s first Black general manager. Instead, Bill wanted to be known for his knowledge of the game and his ability to think quickly. But according to Rubye, Bill’s attitude began to change during Spring Training in 1977. He started to realize the historic nature of his hiring and the role that he could play as a true civil rights pioneer.

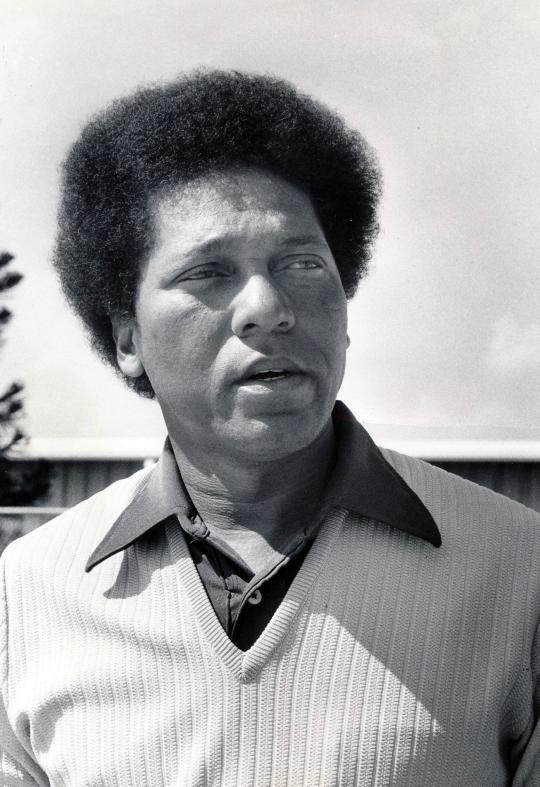

Even before that realization, Lucas wanted to make a splash as GM. During his first winter on the job, Lucas made two major moves to improve the Braves. In mid-November, he signed free agent outfielder Gary Matthews, who succeeded the aging Jimmy Wynn in left field. And then at the Winter Meetings, Lucas pulled the trigger on a blockbuster trade, sending a package of five veteran players and $250,000 in cash to the Texas Rangers for slugging right fielder Jeff Burroughs.

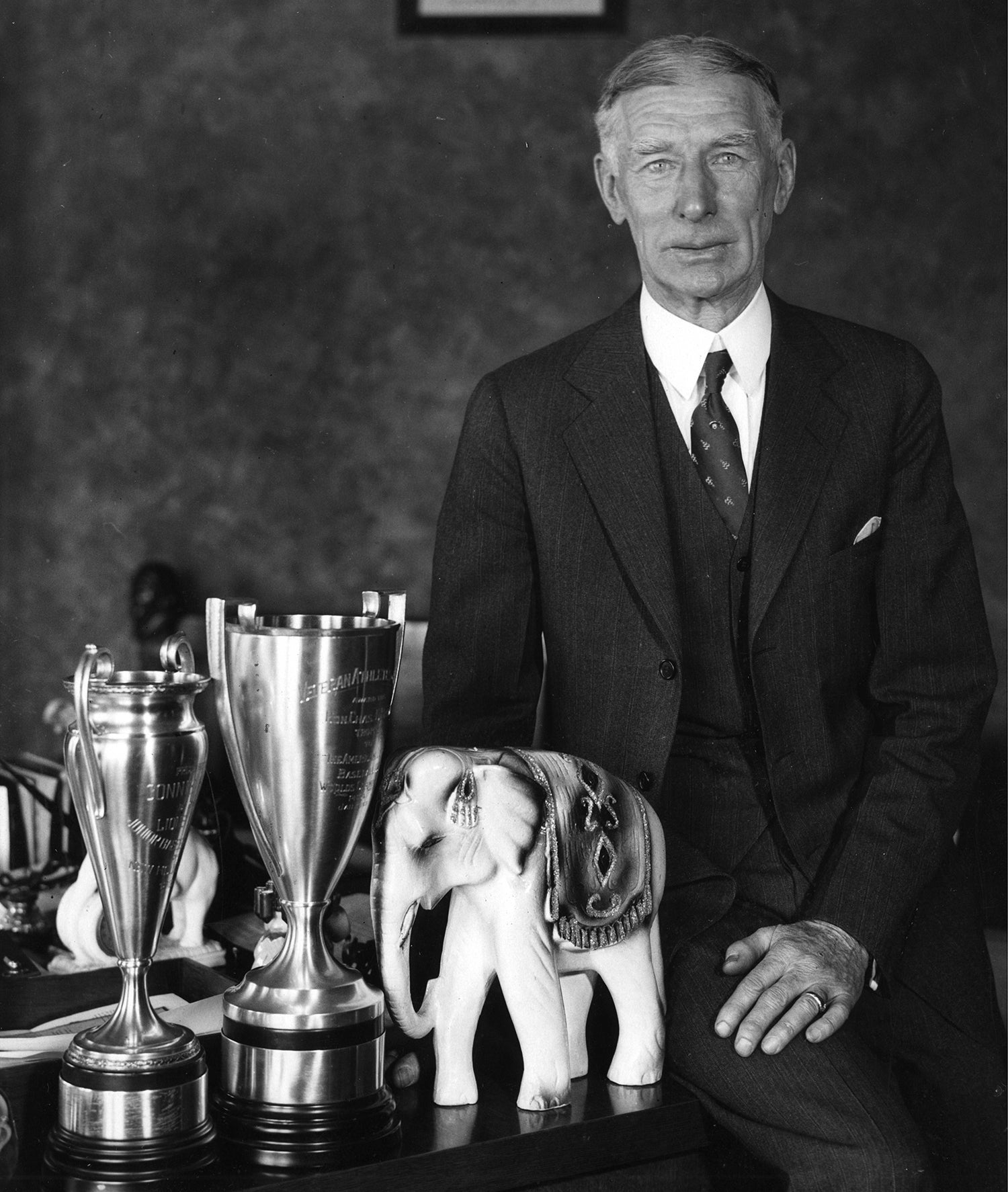

Both 26 years old, Burroughs and Mathews brought power and production to the Braves, but the rest of the lineup did not carry its share of the load. The Braves endured a terrible start to the season, lowlighted by a horrific 17-game losing streak from late April through mid-May. That’s when Turner made an unconventional move. He decided to give his manager, Dave Bristol, a leave of absence, sending him on what he called a “10-day scouting trip.” Turner then appointed himself as the new manager of the still-struggling team. Turner’s tenure as manager lasted for just one game; National League President Chub Feeney determined that under baseball’s rules, an owner could not manage the team, as Connie Mack had done for so many years with the Philadelphia Athletics.

Lucas turned to veteran coach Vern Benson to lead the team for the next game before bringing back Bristol as his manager.

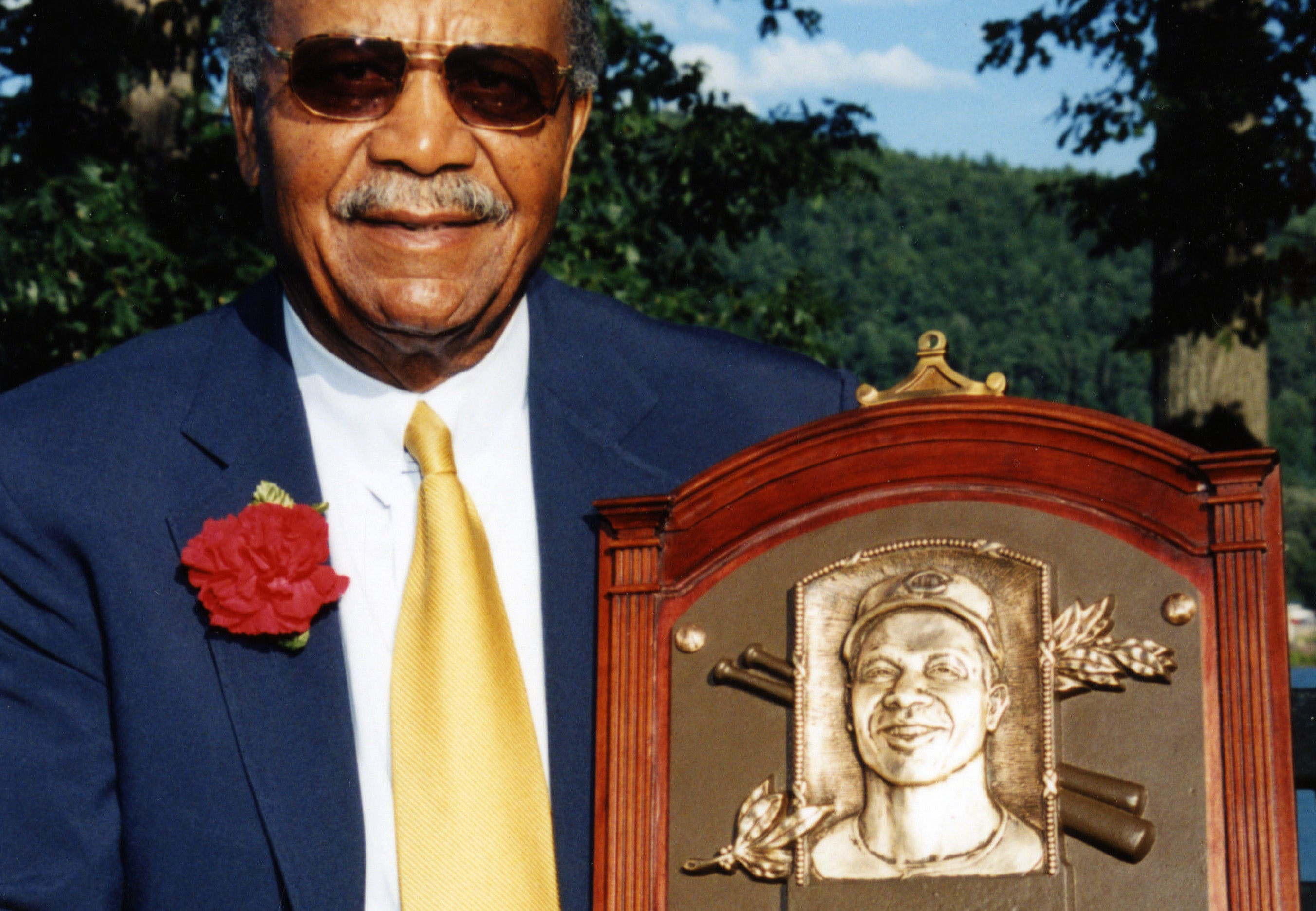

The disappointment of the 1977 season would prompt Lucas to make an offseason change in managers, one that would prove more lasting than Turner’s reign as skipper. Lucas let Bristol go, replacing him with Bobby Cox. At the time, Cox was 36 and mostly unknown, a former third baseman who had become a successful manager in the New York Yankees’ farm system. Little did anyone know that Lucas was bringing in a man who would eventually become a Hall of Fame manager in Atlanta.

Given the Braves’ poor record in 1977, the team owned the first pick in the June 1978 draft. With that first pick, Lucas oversaw the selection of Bob Horner, a slugging All-American second baseman who had starred at Arizona State. Bypassing the minor leagues completely, Horner reported to Atlanta that season, becoming the Braves’ starting third baseman and a cornerstone to a burgeoning lineup.

Horner was the obvious and correct choice as the first overall pick in the draft, but Lucas found other gems in later rounds. They included Steve Bedrosian, who would become a key reliever for the Braves in 1982 and later a Cy Young Award winner in Philadelphia. Lucas and the Braves also uncovered Gerald Perry, a base-stealing first baseman who would play for the Braves from 1983 to 1989.

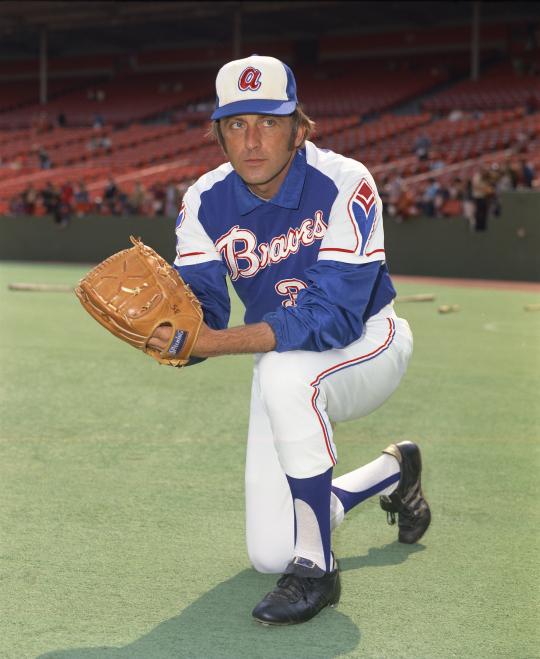

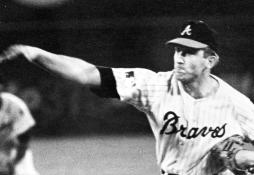

While the draft was productive for the Braves, Lucas found himself fending off more challenges from Turner. One of them involved contract negotiations with Braves ace Phil Niekro, who was scheduled to become a free agent at the end of the 1978 season. Lucas and Niekro agreed to terms on a new deal, only to have Turner step into the negotiations and lower the Braves’ offer. Ultimately Lucas was able to work around Turner’s interference and sign Niekro to a long-term contract, keeping the beloved right-hander in Atlanta through the 1983 season.

Despite the resolution of the Niekro situation, the addition of Horner and the hiring of Cox, the Braves saw only small improvement in 1978. They won 69 games – just eight more than the previous season – a result that proved frustrating for Lucas. But that season also saw the emergence of three important young players for the Braves: the aforementioned Horner, who hit 23 home runs in just over half a season; Glenn Hubbard, who would soon take over at second base; and a young slugger in Dale Murphy, who hit 23 home runs. Murphy would become the cornerstone of the Braves in the 1980s, a two-time MVP, a five-time Gold Glove Award-winning outfielder and a durable team leader.

In the winter of 1978-79, Lucas took a stand-pat approach with his roster, making only one minor trade while hoping that his young talent would improve with experience. Sadly, Lucas would not see the fruition of that plan. On May 1, 1979, while the Braves were playing in Pittsburgh against the Pirates, Lucas watched the game on TV from his home. He saw Phil Niekro win his 200th career game, prompting him to place a congratulatory phone call to the Braves’ ace. Some time after making that call, Lucas suffered a massive cerebral hemorrhage. Taken to a nearby hospital, he remained in a coma. Never regaining consciousness, he died a few days later, passing away on May 5. Lucas was only 43.

The news of Lucas’ death stunned the Braves’ organization. Bobby Cox praised Lucas for his ability to connect with everyone who worked for the Braves. “When you thought of the Braves’ organization, you thought of Bill Lucas,” Cox said at the time. “He knew the organization inside and out and every person from the superstar to the groundskeeper.”

Lucas also showed concern for the family members of those who worked for the Braves, particularly those who faced segregation of a different sort. In 1972, while still serving as the franchise’s farm director, Lucas attended the All-Star Game, which was taking place in Atlanta. On his way to one of the All-Star Game parties, he ran into Susan Hope, the wife of Braves public relations director Bob Hope. Lucas asked Susan to join him at the party, but she informed him that the party was for men only. According to former Braves scout Lee Walburn, Lucas responded, “Look, my people weren’t allowed to enter nice places for years either. Come on, someone’s got to be the first woman to integrate baseball.” Lucas and Susan Hope then entered the room where the party was being held.

Though Lucas was not as famous as some of the game’s most well-known executives, there’s little doubt that he was a pioneer in baseball’s racial history.

At the time of his death, Lucas was the highest ranking Black executive in the game, along with being the only Black general manager. A second Black GM would not arrive until 1993, when the Houston Astros hired Bob Watson to run their organization. Watson would eventually win a world championship with the New York Yankees.

Lucas’ early death prevented him from seeing the impending improvement in the Braves. That began to manifest in 1980, when the Braves finished with a respectable record of 81-80. After a dip to a 50-56 record during the strike-shortened season of 1981, the Braves blossomed in ’82, winning 89 games on their way to an NL West division title. Many of the players who came to Atlanta on Lucas’ watch contributed. Hubbard provided stable defensive play at second base, Horner clubbed 32 home runs, Bedrosian saved 11 games and Murphy emerged as National League MVP on the strength of 36 home runs, 93 walks and 23 stolen bases.

Lucas’ work as farm director and general manager had a huge impact in laying the foundation for the 1982 Braves and their 1983 successors, who won 88 games in finishing a close second to the Los Angeles Dodgers. It’s impossible to know what would have happened if Lucas had lived longer; perhaps the franchise would have enjoyed more sustained success in the 1980s.

This much is certain: For the short time that he lived, Lucas achieved two substantial milestones, becoming a director of a farm system and then the head of baseball operations for a major league franchise. It’s probably safe to say that few baseball executives in their early 40s have been able to match what Lucas did in his 43 years.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum