- Home

- Our Stories

- Gedeon, O'Neill gave their lives during Second World War

Gedeon, O'Neill gave their lives during Second World War

Between them, they played a total of six games in the big leagues.

Harry O’Neill’s Major League Baseball career lasted all of two innings as a defensive replacement for the Philadelphia Athletics in 1939. One game. Zero at-bats.

Elmer Gedeon’s stat line wasn’t much fuller. The one-time Washington Senators center fielder did get some swings in, delivering three hits and one RBI in 15 at-bats before his big-league ledger was complete that same summer.

Although their brief careers would be described as “cups of coffee,” O’Neill and Gedeon would earn places in baseball history after they left the diamond. They would become tragic figures forever linked. Their sacrifices would be ultimate – far more significant than ones listed in a box score.

Of the roughly 500 major-leaguers who fought in World War II, O’Neill and Gedeon would be the only two killed in combat. The deadliest conflict in human history also would claim at least 138 minor leaguers, including Billy Southworth, Jr., a promising prospect and son of Hall of Fame manager Billy Southworth Sr., and two men who would posthumously be awarded Congressional Medals of Honor: Joe Pinder and Jack Lummus.

Although their basepaths never crossed, O’Neill and Gedeon had much in common. Both had been three-sport stars in college – O’Neill in baseball, football and basketball at Gettysburg College in Pennsylvania, and Gedeon in baseball, football and track and field at the University Michigan, where he tied a world record in the high hurdles and was considered a prime candidate for the United States Olympic team. Both were tall for the times – O’Neill 6-foot-3; Gedeon 6-foot-4. Both signed professional baseball contracts shortly after graduating from college in the spring of 1939. And both made their MLB debuts later that year.

O’Neill taught American history and coached football, baseball and basketball at Upper Darby Junior High School in suburban Philadelphia, while Gedeon returned to his college alma mater as an assistant football coach. Both became military officers – O’Neill rising to the rank of First Lieutenant in the U.S. Marine Corps, and Gedeon earning captain’s bars in the U.S. Army Air Force. Both were awarded medals for heroism. And both were 27-years-old at the time of their deaths, leaving many to wonder what might have been.

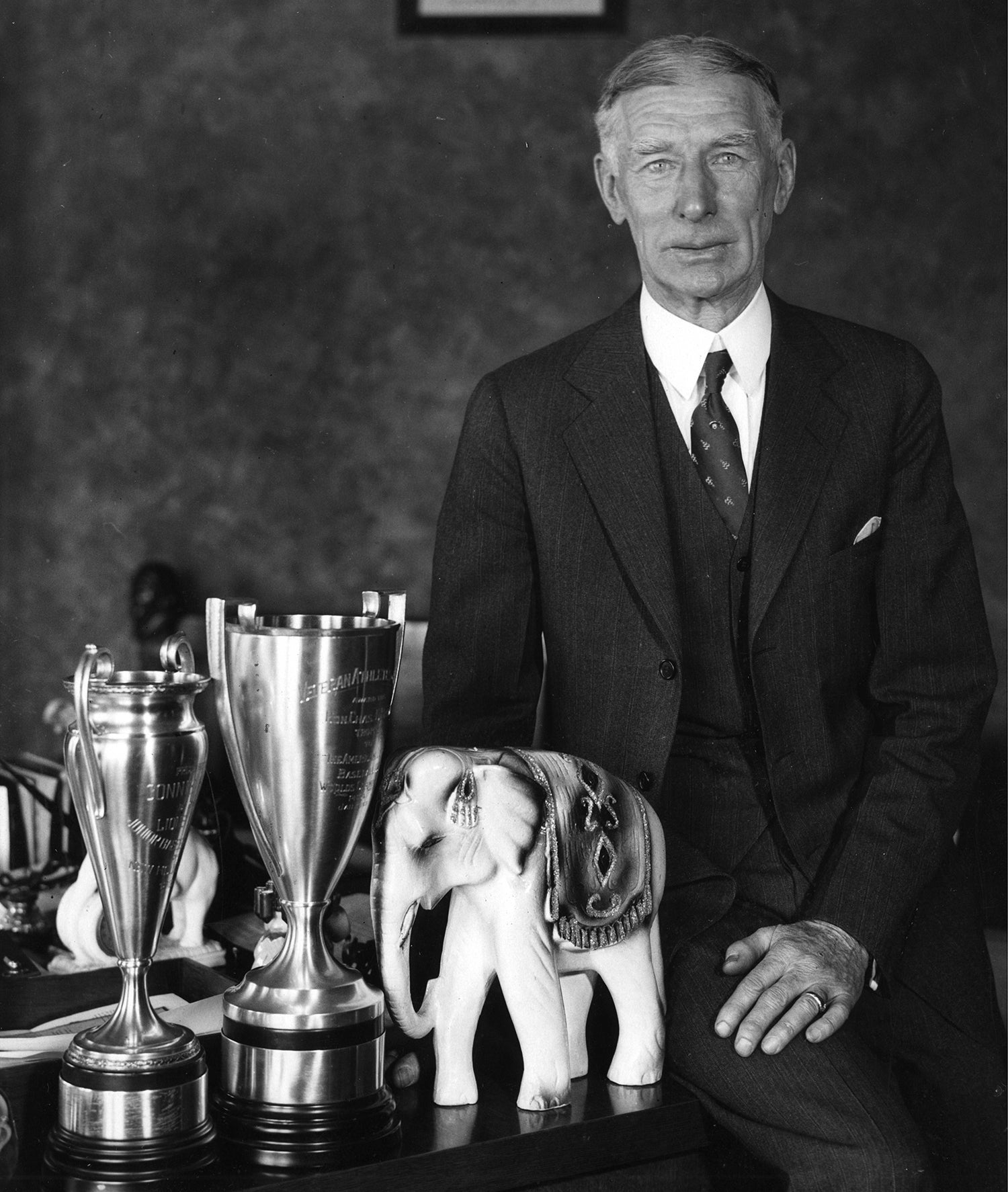

Harry O’Neill led three different sports teams to titles at Gettysburg, but the catcher known fondly as “Porky” loved baseball best. Coached in college by Ira Plank, brother of Baseball Hall of Famer and fellow Gettysburg alum Eddie Plank, O’Neill ignited a minor bidding war between the Athletics and Senators. The Philadelphia native wound up signing a $200-a-month contract with the hometown A’s on June 5, 1939, and was immediately placed on the big-league roster as a third-string catcher behind starter Frankie Hayes and veteran backup Earle Brucker.

Playing time would prove scarce. The lion’s share of O’Neill’s work was spent warming up pitchers in the bullpen. Finally, on July 23, he was given some mop-up duty, catching the eighth and ninth innings of a 16-3 drubbing of the Detroit Tigers and finishing with no plate appearances nor any fielding chances.

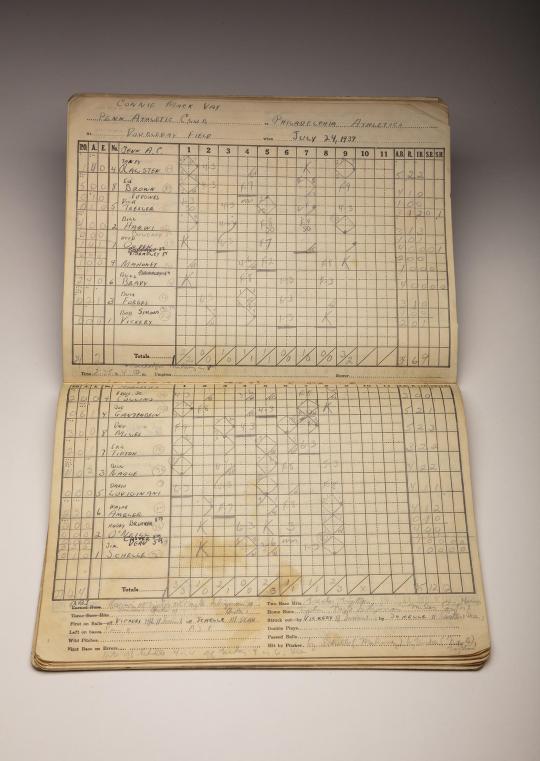

The next day, O’Neill and his teammates took a train to Cooperstown to participate in a “Connie Mack Day” exhibition game as part of the fourth-month long celebration of baseball’s centennial. It marked the first time a major league club played a game at recently constructed Doubleday Field, and O’Neill was given a surprise start. Batting eighth, he went 0-4. He would play in another exhibition game a week later. That would be his last action before being released that September.

The following season, O’Neill batted .238 with a home run and nine RBI in 16 games for the Pittsburgh Pirates’ minor-league team in Harrisburg, Pa., before being released again – this time for good. His short career reminded some of Archibald “Moonlight” Graham, the real-life ballplayer who played one inning with the 1905 New York Giants before being immortalized in the 1982 book, “Shoeless Joe” and the 1989 film, Field of Dreams.

After baseball retired him, O’Neill resumed his teaching and coaching jobs. With the war escalating, he felt a call to duty and enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps Officers Training School in September 1942. While fighting in Japan 21 months later, he suffered a shrapnel wound and spent several weeks in a San Francisco hospital recuperating. He was awarded a Purple Heart and insisted on returning to the Pacific Theater after he recovered.

On March 6, 1945 – 11 days after American soldiers raised a flag atop Iwo Jima’s Mount Suribachi – O’Neill and his fellow Marines fought a day-long skirmish to secure the rest of the island, which the Allies were using as a make-shift base to launch bombers to Tokyo, 750 miles to the north. While O’Neill sought cover in a deep crater, a sniper’s bullet pierced his neck and killed him instantly. Originally buried in Iwo Jima, O’Neill’s remains later were brought to Arlington Cemetery in Drexel Hill, Pa.

“We are trying to keep our courage up, as Harry would want us to do, but our hearts are very sad, and as the days go on it seems to be getting worse,’’ his mother, Susanna, wrote in a heartfelt letter to her son’s former college football coach several weeks after receiving word of Harry’s death. “Harry was always so full of life, that it seems hard to think he is gone. But God knows best, and perhaps someday, we will understand why all this sacrifice of so many fine young men.”

Although he was an All-American hurdler for the Wolverines, lanky Elmer Gedeon was more interested in going for base hits than gold medals. His .320 collegiate batting average and world-class speed intrigued the Senators, who signed the Cleveland native shortly after he graduated from Michigan. After smashing 14 extra-base hits in 67 games for the Senators’ farm club in Orlando, Fla., Gedeon was promoted to the majors in mid-September. His debut was non-descript – one at-bat, no hits and one putout as a late-inning replacement.

But the next day Gedeon made his first start in center field and went 3-for-4 with a walk and an RBI in a 10-9 victory against the Indians team he rooted for in his youth. Impressed Senators manager Bucky Harris told reporters Gedeon would be the team’s starting center fielder the rest of the season, but the skipper had a change of heart after watching Gedeon go hitless in the next three games.

The prospect rode the bench the final two weeks.

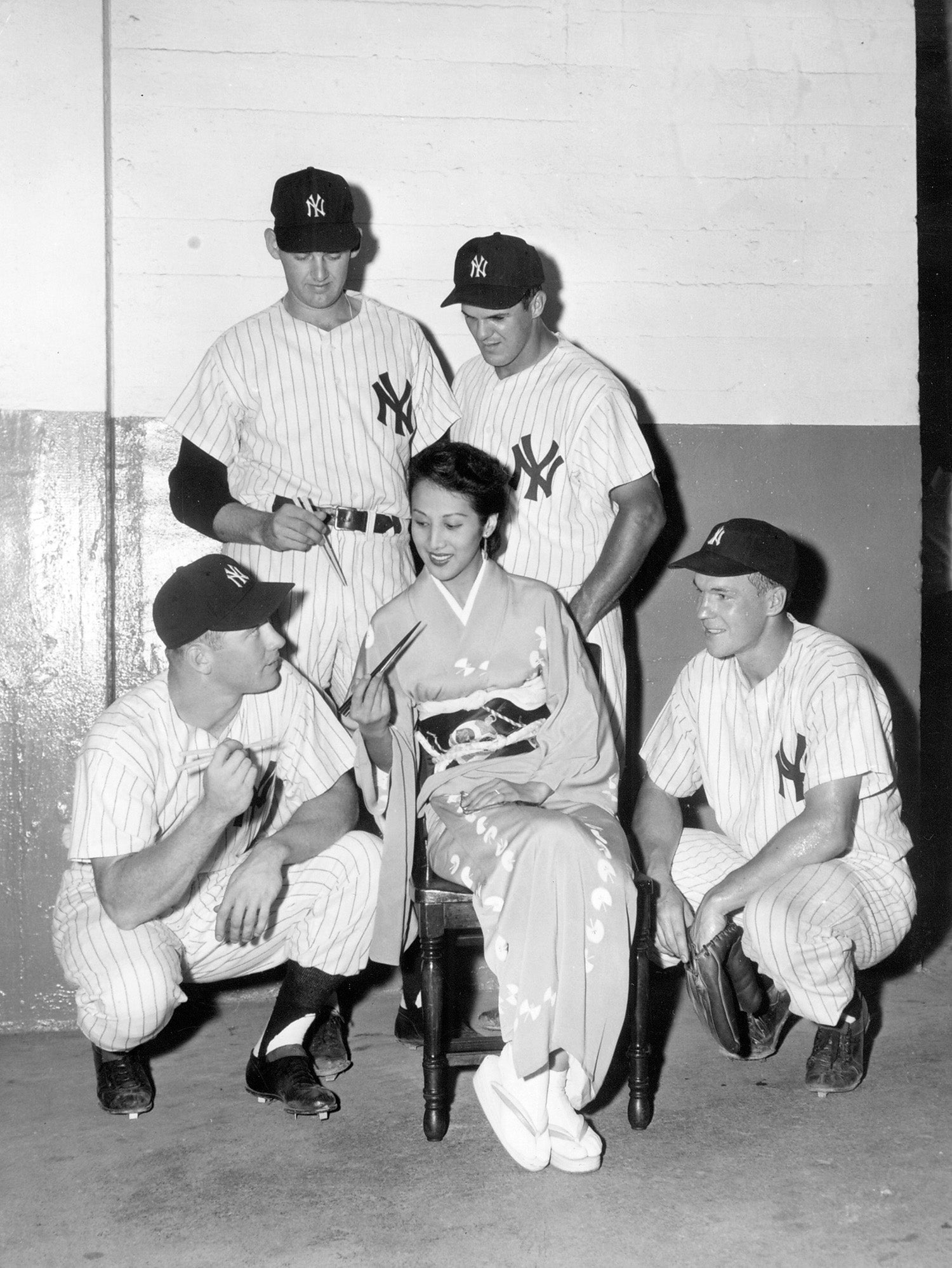

The Senators, though, remained high on him, and invited him to big league camp the following spring, where he was photographed by the Associated Press hurdling over Senators first baseman Jimmy Wasdell. Gedeon spent the 1940 season with the Charlotte Hornets of the Class B Piedmont League, batting .271 with 11 home runs, 20 doubles and nine triples in 131 games. He received a late-season call-up to the Senators, but did not see any action this time around.

That fall, Gedeon returned to Michigan to coach the Wolverines receivers. In January 1941, nearly a year before Pearl Harbor, he was drafted into the Army. He was assigned to the cavalry, but wound up transferring to the pilot training program.

During a training mission near Raleigh, N.C., on Aug. 9, 1942, the B-25 bomber he was navigating, clipped some pine trees and crashed into a swamp shortly after take-off. He suffered three broken ribs but managed to escape. When he realized one of his crewmates was missing, he crawled back into the fiery wreckage and dragged him out. Gedeon suffered severe burns to his face, back, hands and legs – some of which required skin grafts – and lost 50 pounds during his 12 weeks in the hospital. The Army awarded him the Soldier’s Medal for heroism and bravery. Despite his harrowing experience, Gedeon was eager to return to action.

Before departing for England in July 1943, he stopped in Cleveland to visit relatives. “I had my accident; my bad luck’s behind me,’’ he told his cousin. “It’s going to be good flying from now on.” In a wire service story published around that time, Gedeon said he planned to resume his professional baseball career “if the war doesn’t last too long.”

Ten months later, he would fly his last mission. Gedeon took off from Boreham, an airfield in Chesterfield, England, along with 35 other B-26 bombers, on April 20, 1944. According to Robert Weintraub, author of “The Victory Season: The End of World War II and the Birth of Baseball’s Golden Era,” they were headed to Esquerdes, France, a launch site for the V-1 buzz bombs Adolf Hitler used to terrorize England. After Gedeon’s plane dropped its bombs, antiaircraft fire ripped through its undercarriage. The plane burst into flames. Gedeon and five of his crewmates died.

Gedeon initially was reported as “missing in action,” and it wasn’t until a year later his family received word his grave had been located in a small British Army cemetery in France. His remains were returned and buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

Scott Pitoniak is a freelance writer from Penfield, N.Y.