- Home

- Our Stories

- Legacy of ‘Ball Four’ lives on at Museum

Legacy of ‘Ball Four’ lives on at Museum

Big league pitcher Jim Bouton wrote a book that often courted controversy and elicited scorn around the country even before its publication. Today, “Ball Four” and its behind-the-scenes look at a baseball life is considered a classic of the genre.

Published in June 1970, “Ball Four: My Life and Hard Times Throwing the Knuckleball in the Big Leagues” has reportedly sold more than 5.5 million copies over the decades.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

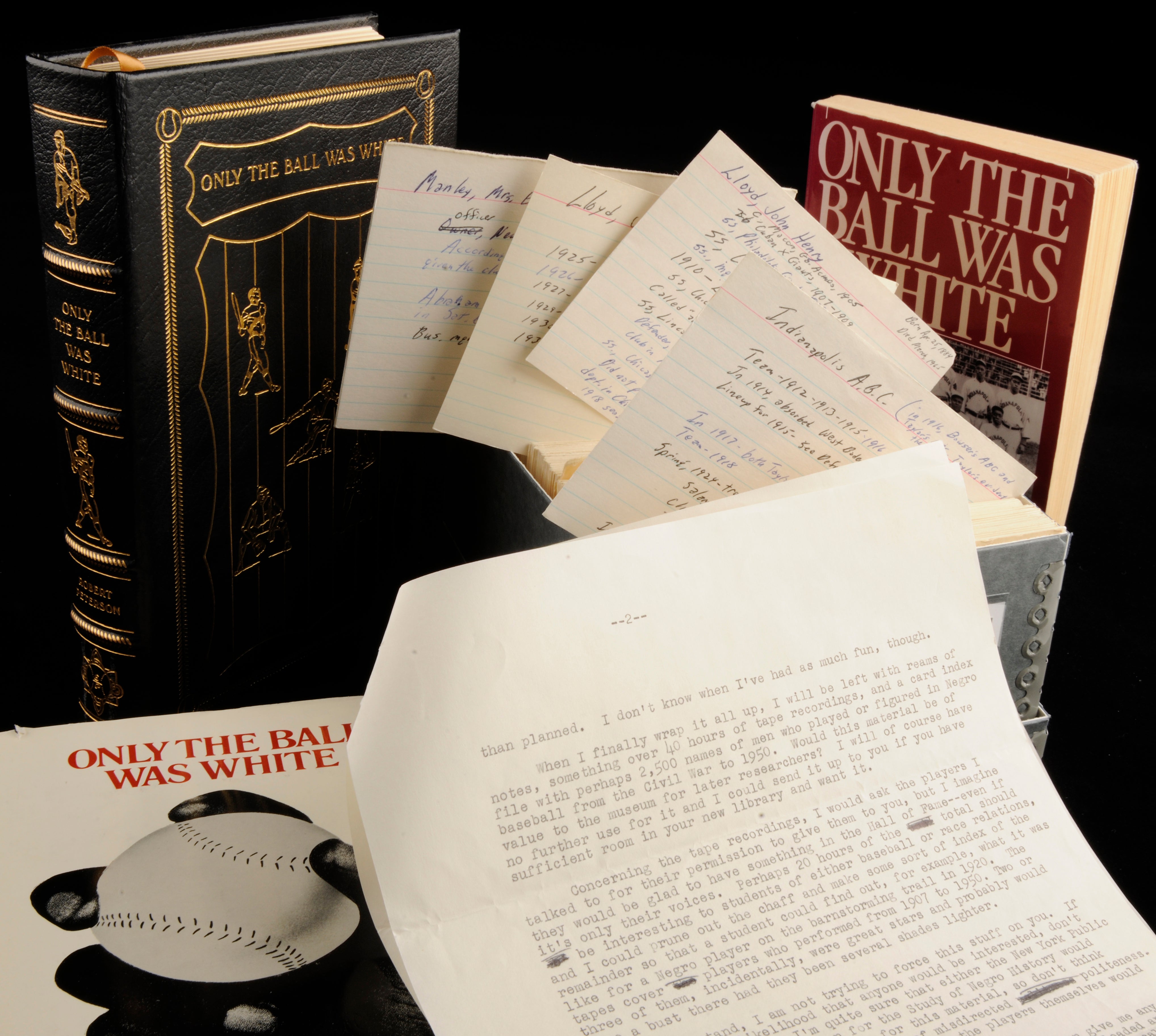

Four copies of the irreverent bestseller are in the collection of the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, as well as a unique piece of artwork that caricatures the legacy of Bouton to baseball fans.

“’Ball Four’ is widely considered to be a seminal work in the history of baseball literature,” said Hall of Fame Librarian James Gates. “When the book was first published it was immediately celebrated and denigrated, a realm of notoriety in which it still exists.

“Regardless of any reader's opinion on its contents, it did create an entire new class of sports literature, the ‘tell-all’ autobiography, a genre in which there are few rules. This stylistic presentation of sports figures off the field is still going strong, and owes a certain amount of gratitude to the foundational endeavors of Jim Bouton.”

The groundbreaking tome, written by Bouton and edited by Leonard Schecter, irritated the baseball establishment for its revelations – both on and off the field – about players.

“I did it because I wanted to entertain people,” the 31-year-old Bouton told The New York Times in June 1970, “and I did it because I wanted some things told from the inside, like how general managers cheat players, and because – let’s not kid ourselves – I wanted to make some money. But mostly I did it because I wanted to go down in history as the guy who wrote the book you absolutely have to read if you want to understand something about this American subculture called baseball.”

“Let kids start thinking about some real heroes instead of phony heroes. Baseball is strong enough to withstand an inside look.”

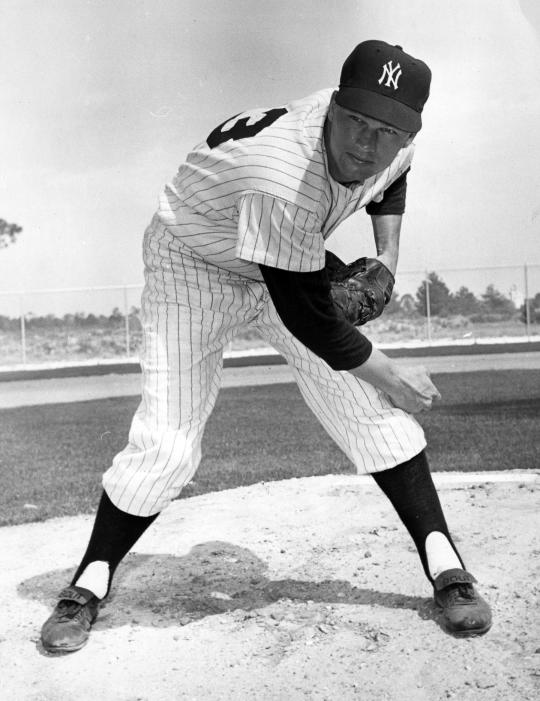

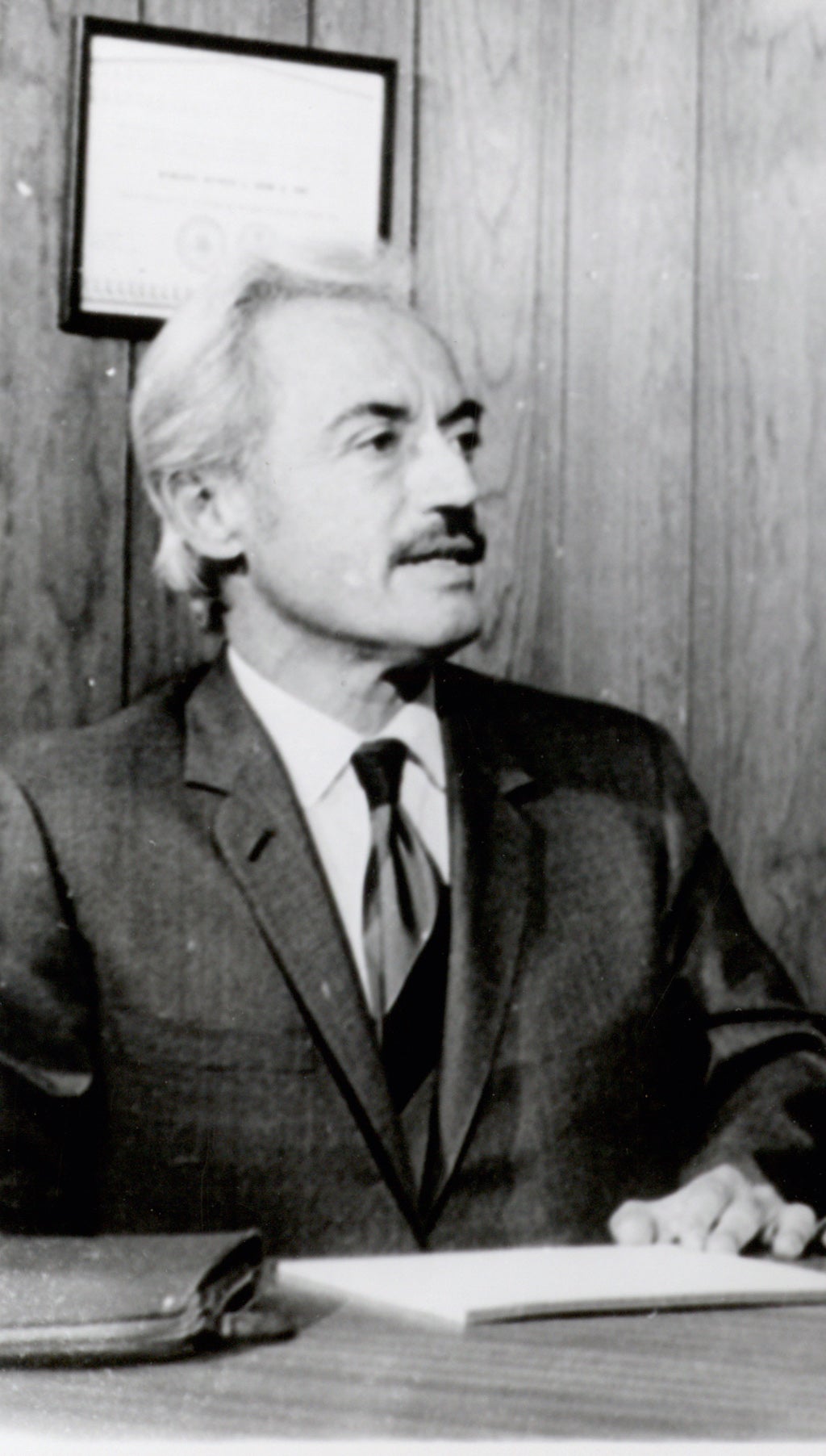

The outspoken Bouton – who passed away in 2019 at the age of 80 – gained fame on the field with the New York Yankees, using his strong right arm to win 21 games for the Yankees in 1963 and 18 in 1964, along with two World Series victories. The blond haired and intelligent player, nicknamed “Bulldog,” threw so hard his cap would fall off on almost every pitch.

“Ball Four” tells the story of Bouton’s time in 1969 as a knuckleball-tossing member for the Seattle Pilots and Houston Astros, but the non-fiction book often harkens back to his days in pinstripes.

Even before the book’s release, though, Baseball Commissioner Bowie Kuhn had an almost two-hour meeting with the then-Houston Astros hurler – accompanied by Major League Baseball Players Association Executive Director and 2020 Hall of Fame electee Marvin Miller – to discuss the revealing diary on June 1, 1970.

Time Magazine called the book “Fast, flip and often funny” and Publishers’ Weekly referred to it as “funny, lively and just about the best.”

“I advised Mr. Bouton of my displeasure with these writings and have warned him against future writings of this character,” Kuhn said afterward, adding that no other disciplinary action was necessary.

The Washington Post’s review called it “A genuine, carefully crafted, immensely readable work,” the critic adding, “What is most memorable is Bouton’s own personality, his indomitable belief in values that transcend all this pettiness almost gloriously, and his absolute delicious wit.”

There were also plenty of critics of the frank account of Bouton’s baseball career, with baseball columnist Dick Young calling the author a “social leper,” while Bill Veeck, the longtime owner whose progressive ideas often placed him outside the baseball orthodoxy, said: “I’ve spent most of my life around ballplayers. I know their peculiarities. But there are certain things that achieve nothing for no one. I think we are entitled to have some heroes left.”

Sports columnist Robert Lipsyte, in The New York Times, wrote, “(Bouton’s) anecdotes and insights are enlightening, hilarious and, most important, unavailable elsewhere. They breathe a new life into a game choked by pontificating statisticians, image-conscious officials and scared ballplayers.”

In a letter to the editor that appeared in the Chicago Tribune on Aug. 5, 1970, Carol Nappe, who had recently read “Ball Four” and enjoyed it immensely, wrote, in part, that ballplayers are people, too, and like to have fun once in a while.

“I will admit that Bouton could have used less-profane language. I think it’s all right to swear, but Jim used those type of words a little too often,” Nappe wrote. “‘Ball Four’ is one of the funniest books about baseball ever written.”

In a recent telephone interview with Mitchell Nathanson, the author of the recently released “Bouton: The Life of a Baseball Original,” he said the whole point of the book was to give the reader a feeling of what it would be like if you could live your life as a major leaguer and be in the locker room.

“A book with decorum about a major league locker room is going to be a false book. Bouton’s book gave the reader an honest picture of what it was like to be in a place like that,” Nathanson said. “This is an artifact, not a piece of investigative journalism.

Asked whether Bouton had any regrets about writing “Ball Four” in his later years, Nathanson said: “He was always very proud of it. Near the end of his life, with a lot of time to reflect, he knew that if ‘Ball Four’ was going to be his legacy that was something he was very comfortable with it.”

The iconic last line of "Ball Four" is, "You spend a good piece of your life gripping a baseball and in the end it turns out that it was the other way around all the time."

In his review of “Ball Four” for The New York Times that appeared on June 19, 1970, Christopher Lehmann-Haupt wrote, “And (Bouton) is candid about himself, too, and paints us a highly engaging portrait of a sensitive young man in love with a silly game and living through a year of crisis.”

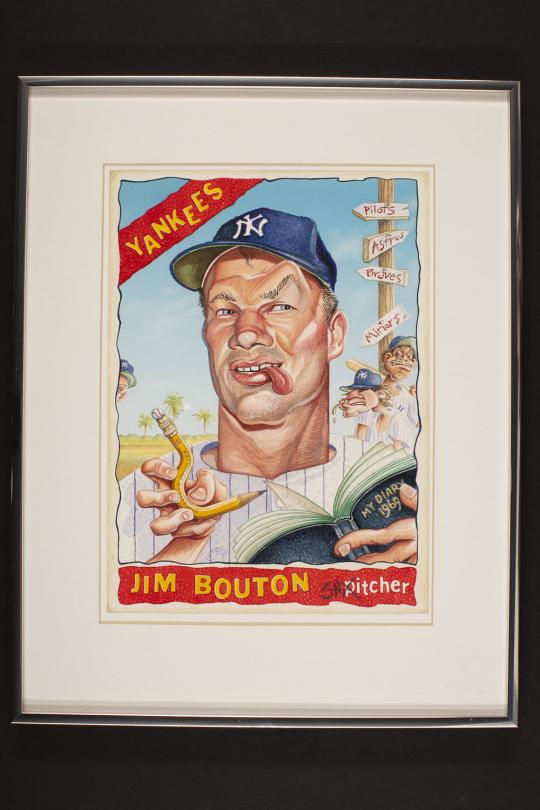

Well, artist Stewart McKissick also created “a highly engaging portrait” of Bouton that now calls Cooperstown home. Based on a 1966 Topps card of Bouton, the 8 inch by 10 inch artwork, matted and framed, was part of a larger collection donated to the Hall of Fame in 2018.

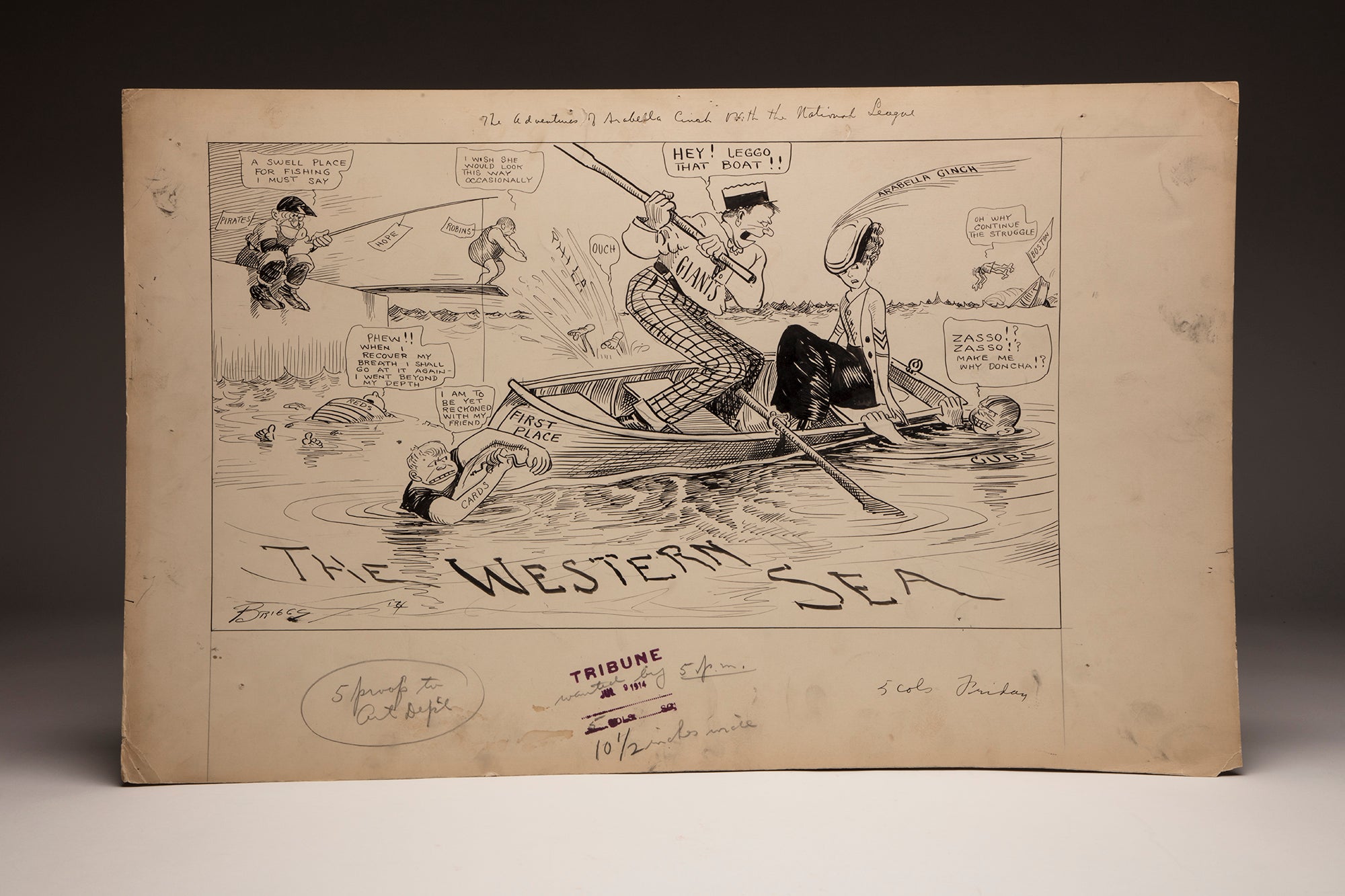

In 1992, the Hall of Fame hosted an exhibit entitled “The Artist and the Baseball Card.” Organized by Murray Tinkelman, who taught illustration at Syracuse University, it featured artists using a variety of media to create oversized baseball cards. The Tinkelman collection donated to the Hall of Fame features the work of over 150 artists and 212 total pieces.

Artist selections ranged from Ty Cobb and Ted Williams, to Dwight Gooden and Jose Canseco. Some were replicas of cards that existed, others caricatures or cartoons.

“I grew up a Pittsburgh Pirates fan, during the golden age of Roberto Clemente and Willie Stargell, attending many games at Forbes Field and Three Rivers Stadium,” wrote McKissick, a freelance illustrator for 30 years and currently professor emeritus at Columbus College of Art & Design, in a recent email.

“I originally drew Stargell for this show, a very straightforward copy of a card done in charcoal. But I was in the process of changing my style, going for a more caricatured/cartoon look, influenced by things like Mad magazine. So I decided to do a second one reflecting this, and chose Jim Bouton.”

Acknowledging he still has his 1970 copy of “Ball Four,” the one he read at age 13 in study hall, the adolescent McKissick found the book “engrossing, a bit ‘dirty,’ and above all hilariously entertaining.”

“I was excited to try and capture as many elements of the book as I could into my reworked version of the card,” McKissick wrote. “I did a watercolor painting, adding references to his various teams on the sign behind him, showing him keeping the diary in 1969 with a knuckleball pencil held in the strange grip pictured on the book’s cover, and threw in some angry teammates about who he was telling tales. I changed ‘pitcher’ to ‘snitcher,’ and had him raising an eyebrow and sticking his tongue out.”

Ironically, Bouton, when asked by Tinkelman, refused to sign the artwork, claiming it made him look “lascivious.”

“At the time, I was very disappointed in Bouton’s reaction,” McKissick wrote. “It is a caricaturist’s job to poke fun after all, and Bouton certainly took his shots at many folks and arguably had a lot of ‘lascivious’ content in ‘Ball Four.’ But over the years I came to rather enjoy the way the whole event unfolded, just as an editorial cartoonist enjoys getting under a subject’s skin.

“I never wished him any ill will and continued to follow any news I saw on him. I still admire his wit and nerve.”

“The Artist and the Baseball Card” exhibit travelled around the country for five years, but when the artists heard they were going to be displayed at the Hall of Fame, according to Tinkelman’s wife, who coordinated the tour, “they were more excited than if they had been told they were going to be hung in the Louvre.”

Bill Francis is the senior research and writing specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum