- Home

- Our Stories

- In all fairness, Appling still king of foul balls

In all fairness, Appling still king of foul balls

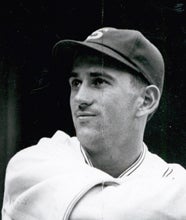

On April 22, 2018, San Francisco Giants first baseman Brandon Belt had a 21-pitch at-bat in the first inning against Angels righty Jaime Barria, setting a big league record that dates back to 1988, the year accurate pitch counts began being recorded throughout baseball.

But Belt still has a ways to go to catch the apocryphal foul ball king, Luke Appling, whose prowess with the bat launched a thousand stories.

Belt’s plate appearance, which lasted nearly 13 minutes, included 16 foul balls before he flew out to right field. Belt saw a total of 40 pitches in five plate appearances this day, including 22 foul balls with a two-strike count.

The previous record – since 1988 – was a 20-pitch at-bat by the Astros’ Ricky Gutierrez against the Indians’ Bartolo Colon on June 26, 1998. But if the decades of tales are to be believed, Appling is likely the undisputed king of the foul ball.

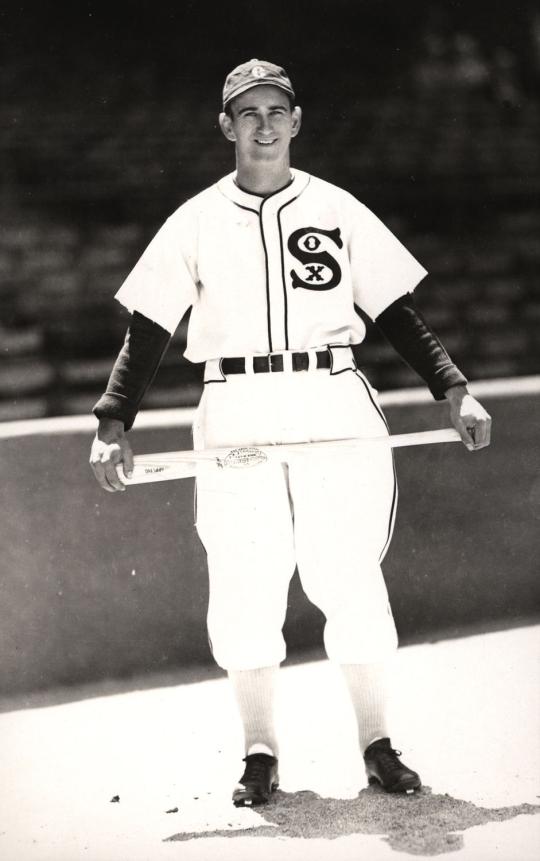

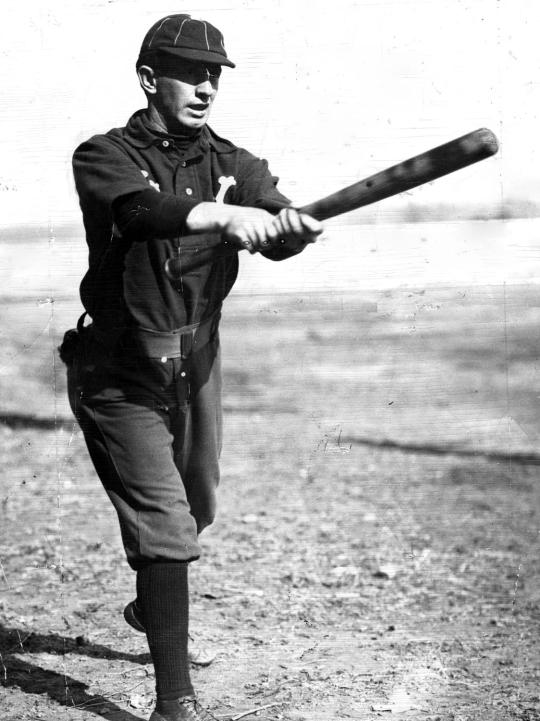

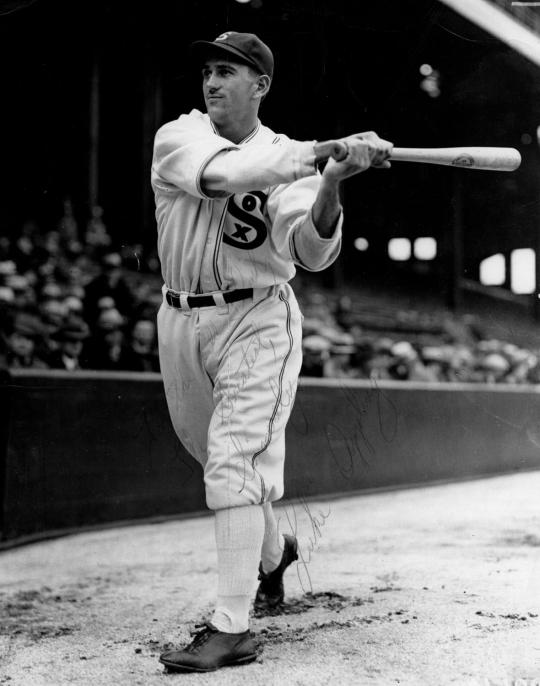

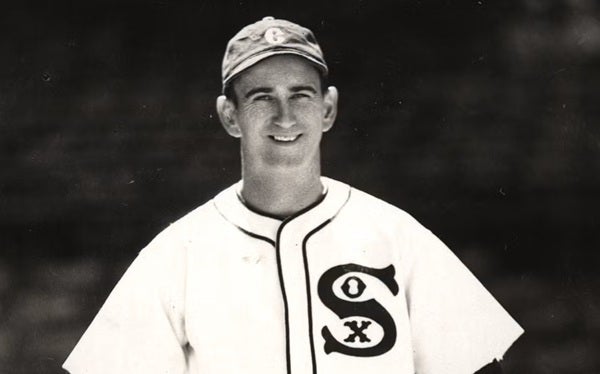

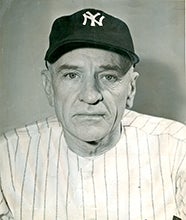

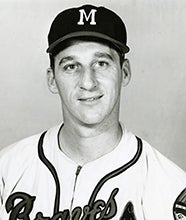

Considered a true artist with a bat in his hand, Appling had a 20-year big league career, from 1930 to 1950, all spent with the White Sox. A member of the National Baseball Hall of Fame Class of 1964, he was a seven-time All-Star who finished his career with 2,749 hits, a .310 batting average, and whose 2,218 defensive games as a shortstop is eighth on the all-time list. But despite the gaudy credentials, Appling may be best remembered for his ability to hit foul balls.

“Hitting fouls defeats the strategy of the team on the field and can drive a pitcher crazy,” said Appling in a 1948 interview with the Sporting News. “I’ll admit fouls don’t attract people in to the park, yet in the book a foul is just as much a part of the game as a fair line drive, and is recognized as a wearing part of baseball.”

Arguably the best place-hitter of his era, Appling was right-handed batter who became a tremendous opposite-field hitter. Former major league hurler Red Oldham, a minor league teammate of Appling’s with the 1930 Atlanta Crackers, convinced the young infielder to give up being a pull hitter and go the opposite way. According to “Old Aches and Pains,” who finished his career with 440 doubles and 102 triples but only 45 home runs, it took him “about three years, just continuously working. But it finally came, and then I could hit the ball anywhere I’d want.

“I happened to have a knack for slicing the ball to right field. This is unusual for a right-handed batter, and I capitalized on it. Usually, they pull to left,” Appling said in 1948. “Because I could place a ball between second and first and into short right field from a right-hand stance, I was called upon to often hit behind the runner on those hit-and-run plays. I had a responsibility to protect the runner going down to second.

“That’s why I fouled off those in-between deliveries that I didn’t like. Too good to pass up, but not good enough to hit at. If I took what the pitcher served me at his discretion, I would have grounded into a double play – the very thing I was trying to avoid.

“I never popped any fouls behind third base. I used to pull a lot of them down the first-base line, and the wind coming in from centerfield at Comiskey Park used to help. It would catch a fly ball to right and, because of the way the ball was spinning, would curve it outside the foul line. That big scoreboard they have above the bleachers nowadays (in 1948 at Comiskey Park) cuts off a lot of that wind.”

Appling often said the one pitch he couldn’t handle was the one that came in over the middle of the plate. “I couldn’t handle that as easy as the others and do with it what I wanted.”

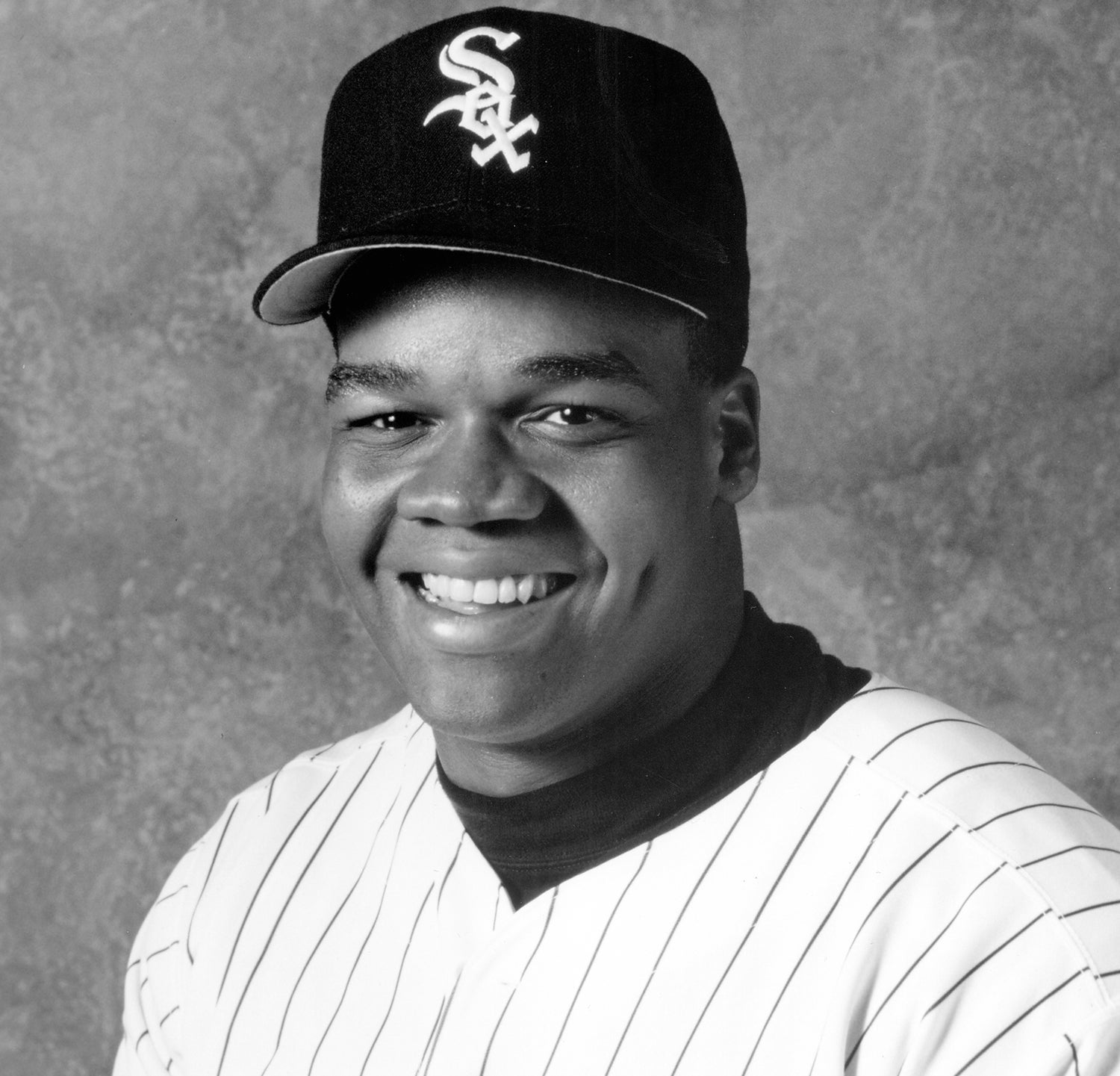

Appling, who like Willie Keeler could “hit ‘em where they ain’t,” would go on to not only bat at least .300 in 14 seasons, but capture American League batting championships in 1936 (.388) and 1943 (.328). The only White Sox player to win a batting crown until Frank Thomas led the Junior Circuit with a .347 mark in 1997, Appling still holds the single-season batting average mark for shortstops with his .388 effort in 1936.

“One year the White Sox publicity man bet me a hat that I couldn’t hit eight home runs,” was quoted by the Associated Press in 1964. “I had eight by July 4, but I was hitting only .260. I never did hit anymore home runs, but I wound up hitting .300. I never got the hat, either.”

Despite his offensive prowess, Appling also had a well-earned reputation of being one of the few batters with who would hit endless foul balls by design, often being a singular source of frustration for both pitchers and fans. Today’s pace of play edicts would be fruitless with Appling in the game.

“I know I made myself unpopular with the fans on the road by staying up at bat for 10 minutes while I fouled off eight, 10 or 12 pitches, and I know the hurlers didn’t love me for making them work overtime,” said Appling in 1948.

Chicago Tribune sports columnist Irving Vaughan was an eyewitness to Appling’s tactics.

“Luke is the foulingest foul ball perpetrator of all time,” Vaughan wrote in June 1947. “With him it is an art, but he can’t explain logically how he does it. Pitchers like him personally because he’s such a congenial soul, utterly lacking in temperament both on or off the ballfield; but one and all they have a professional hatred for him. It’s enough worry for them to keep him from denting their armor with a base hit. But those foul balls! He wears out the pitchers, and makes it more aggravating with his grin and nonchalance. Trying to dust him off is no solution. He not only is too elusive but can’t be ruffled by such tactics.”

Appling told the Chicago Tribune in 1960 that if he was trying to get a real good pitch and the ball was just about over the plate, but a little too close, he’d just reach out and foul it off, waiting for a good one to come by.

“I don’t know if I ever hit 20 fouls in a single time at bat. I wasn’t counting them,” he added. “Once I hit a dozen in a row off Dizzy Trout, and he got so sick and tired of it, he threw his glove at me and hollered, ‘You so-and-so, let’s see you foul that!’ Doggoned if I didn’t foul that off, too, and the umpire fined ol’ Diz for throwing the glove. Then he was really sore!”

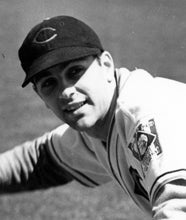

Don Kolloway, Appling’s second-base partner for seven years, recalled the specific hot and muggy day at Comiskey Park in a 1991 interview with the Chicago Tribune.

“I remember it like it was yesterday,” Kolloway said. “First time up, Luke fouled off six or seven pitches. Second time, he fouled off eight or nine. The third time he started doing it again. And Dizzy Trout, the sweat pouring down his face, shouted, ‘Here, Luke, foul this off, too!’ And Trout threw his glove at him.”

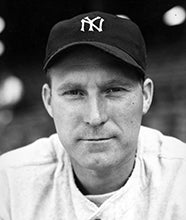

Hall of Fame pitcher Red Ruffing, in a 1970 interview with the Chicago Tribune, said that “Luke just stands there and wears you out. I remember the day I slipped two strikes by, and then he just kept fouling the good pitches until he worked me for a walk. Mike Kreevich was the next batter and he cleaned the bases because I had nothin’ left.”

Even good friends could be on the receiving end of Appling’s torturous treatment.

“My best friend was Spud Chandler – we used to go bird hunting together – and he was comin’ back from an injury when I started foulin’ him off, hopin’ to wear him down to get a walk,” Appling told the Chicago Tribune in 1982. “Finally, after 12 or 14 fouls, I got my walk and as I was goin’ to first base Spud yelled, angrier ‘n heck, ‘Just wait ‘til I get strong. I’m gonna throw the next four at your head.’

“Well, I forgot! And the next time we got to New York, sure enough – phoom, phoom, phoom! – he threw four fast ones at my head. I just ribbed him that he wasn’t any closer than the last time.”

Appling’s unique skill of foul-ball-hitting could also be used in mischievous ways.

“I always liked to scald it into the dugout now and then, just for fun,” said Appling. “Casey Stengel used to have everybody on the bench watching for my hit-and-run. With gloves on.”

“We were riding Appling real hard one day,” said Hall of Fame catcher Bill Dickey. “In those days we’d say mean things. Luke decided to resent some highly masculine statement, so he hit eight straight foul balls into the Yankee dugout. My, how that guy could place a ball.”

Appling’s vengeance could also play out against the front office. White Sox infielder Dario Lodigiani, in a 1990 interview with the Chicago Tribune, told of the spring of 1941 when Appling held out for more money.

“Luke was asking for $20,000, and all they would offer was $17,500. Luke really screamed; he wanted the 20 grand. The club won. He held out for two, maybe three weeks and then signed for $17,500,” Lodigiani said. “When he reported to spring training, Luke told us, ‘I’ll make it cost ‘em. I’ll just keep fouling those balls in the stands.’

“Bob Kennedy was with the Sox then, a young ballplayer. And Kennedy began counting Luke’s foul balls. From spring training until about two weeks into the season, Luke already had hit more than 400 foul balls – balls that went into the seats. Finally, Dykes (White Sox manager Jimmy Dykes) told him to cut it out.”

Defensive shifting in the modern game is prevalent, but when Indians player/manager Lou Boudreau incorporated it against Ted Williams of the Red Sox in the mid-1940s it became national news.

“My fouls didn’t inspire the whole team to move over, like for Ted Williams,” explained Appling to the Sporting News in 1948. “They merely shifted the infielders for me. For Williams they over-shifted the infield, the outfield, the groundskeepers, the ushers and the peanut vendors. Williams swings left-handed. Come to think of it, I guess I was flattered by the greatest mass movement against a right-hander in my time. I couldn’t hit with half the force of Williams. I simply sized up the defense and poked the ball through holes.”

Ironically, Appling was in the news late in life for a homer he hit in a 1982 old-timers' game at the age of 75. The shot, hit off 61-year-old Warren Spahn, went into the left-field stands.

“It was a good pitch," Appling said afterward, “and I just swung away.”

Appling passed away in 1991 at the age of 83.

Bill Francis is the senior research and writing specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum