- Home

- Our Stories

- MLB All-Star Game created a blueprint for other leagues to follow

MLB All-Star Game created a blueprint for other leagues to follow

Arch Ward was born in 1896 in Irwin, Ill., about 55 miles south of Chicago, and grew up dreaming of playing for his beloved White Sox.

Those dreams, though, were dashed early by poor eyesight and sloth-like speed. Ward would need to find another way to make an impact on the game of baseball, and he would do so by wielding influence rather than a Louisville Slugger. Years later, as a powerful, well-connected sports editor and promoter, this man of many caps put on his thinking cap and created an event that gave baseball’s biggest stars an opportunity to shine.

On July 6, 1933, Ward’s idea for a Major League Baseball All-Star Game to coincide with that summer’s World’s Fair in Chicago became a reality. As 47,595 fans sought respite from the throes of the Great Depression at Comiskey Park, a 38-year-old Babe Ruth in the twilight of his marvelous career rose to the occasion once more by homering to propel the American League to a 4-2 victory against the National League.

“Wasn’t it swell – an All-Star game?’’ the ebullient New York Yankees slugger said afterward. “Wasn’t it a great idea? And we won it, besides.”

This “Game of the Century,” as Ward billed it, was supposed to be a one-hit wonder, but was so well-received by players and fans that the AL and NL owners decided to make it an annual event.

The Negro Leagues thought it was a swell idea, too, and wound up hosting their first East-West Game two months after the white majors debuted their All-Star Game. And just as Ruth had christened the AL-NL shin-dig with a homer, so, too, did slugger Mule Suttles in Black Baseball’s first star fest, also played at Comiskey. Suttles, a future Hall-of-Famer, wound up smashing a home run and a double to power the West to an 11-7 victory.

The East-West Game would become “the pinnacle of the Negro League season,’’ wrote esteemed Black baseball historian Larry Lester. “It was an all-star game and a World Series all wrapped into one spectacle.”

And like the AL-NL spectacle, it had been inspired by Ward. Though bespectacled and slow of foot, Ward proved he was a fleet-of-mind visionary. Ninety years later, his creation remains a Midsummer’s Classic, one of the most anticipated events on the baseball calendar.

Although Ward’s brainstorm is officially recognized as the first All-Star Game, the reality is that the roots for such crème-de-la-crème affairs can be traced all the way back to the recognized start of organized baseball in 1858. As MLB’s official historian John Thorn has written: “Picked nines from the top clubs of New York [that year] played against those selected from the elite clubs of the rival city, Brooklyn. New York won the match, two games to one, and ushered in the age of professionalism.”

Thorn cites an exhibition between Rube Foster’s X-Giants Black World Series champs and the Kingston, N.Y. Colonials on Sept. 21, 1903 as perhaps the first professional in-season all-star game. Foster won 51 games that year and would go on to create the Negro National League in 1920 and earn a plaque in Cooperstown in 1981. He would add to his lofty ’03 win total by defeating Kingston, a Class D minor-league team, 3-2.

Other all-star games would follow, such as a July 24, 1911 benefit exhibition featuring Ty Cobb, Walter Johnson and Tris Speaker that helped raise $12,914 for Addie Joss’s widow and children following Joss’s death months earlier from tubercular meningitis. The All-Star team defeated the Cleveland Naps, 5-3, in a game that Society for American Baseball Research writer John Husman said, “demonstrated the public’s appetite for an all-star game.”

Four years later, Baseball Magazine editor F.C. Lane broached the idea of an All-Star Game between the NL and AL but was snubbed by the sport’s leadership, according to Thomas Littlewood, author of the Ward biography, “Arch – A Promoter. Not a Poet.”

The public’s appetite wouldn’t be sated until nearly two decades later, and it would take a perfect storm of events to make it happen.

America was feeling the full effects of the Great Depression by 1933. Unemployment had skyrocketed to 25 percent. Nearly 4,000 banks had closed that year alone. Hundreds of thousands of people had been rendered homeless, many of them living in cardboard boxes in shanty towns that became known derisively as “Hoovervilles,” after Herbert Hoover, who had been president during Wall Street’s collapse four years earlier.

Like virtually every business, Major League Baseball had taken a huge hit, with attendance plummeting 40 percent from a peak of roughly 10 million in 1930.

Despite the economic woes, Chicago, which was celebrating its centennial in 1933, decided to go ahead with plans to host the World’s Fair – officially named “A Century of Progress International Exposition.” Seeking a way to boost attendance, Windy City mayor Ed Kelly approached Chicago Tribune publisher Colonel Robert McCormick about staging a sporting event during the fair, and McCormick contacted Ward, who was the Tribune’s sports editor at the time. Though just 36 years old, Ward already was well on his way to becoming the “Cecil B. DeMille of sports.”

While a student at Notre Dame, he had made a name for himself doing publicity for legendary Irish football coach Knute Rockne. In his role as sports editor, Ward had become quite influential – not only in Chicago, but nationwide. He immediately suggested a big-league All-Star Game, and shrewdly sold it to MLB Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis and the owners, several of whom initially balked at the proposal.

To heighten interest in the game, Ward suggested giving fans the power to elect the All-Stars, with ballots running in major newspapers nationwide. At Ward’s urging, John McGraw was coaxed out of retirement to manage the NL squad, while the venerable Connie Mack agreed to skipper the AL team. The game wound up being a rousing success.

“That’s a grand show, and it should be continued,’’ Landis said afterward. At the next owner’s meeting, a measure was passed to make the “Game of the Century” an annual event to be played in a different city each season.

The idea for the Negro Leagues All-Star game also was championed by sportswriters, as Roy Sparrow of the Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph and Bill Nunn of the Pittsburgh Courier pitched their proposal to Gus Greenlee, the owner of the Pittsburgh Crawfords, a Black baseball juggernaut. Greenlee pointed them in the direction of Chicago American Giants owner Robert Cole and Comiskey was secured for Sept. 10, 1933.

Though played on a drizzly day, 19,568 fans turned out for the game, which outdrew the crowd that showed up to watch the Cubs play crosstown at Wrigley Field that afternoon. The mainstream press pretty much ignored the East-West Game, but the historically Black newspapers provided blanket coverage, and used it to push for integration.

“Professional baseball has been and is losing thousands of dollars yearly by its narrow and asinine prejudiced attitude in the operation of the nation’s game,” editorialized the Chicago Defender. “We ask again: What is the matter with baseball? The answer is plain prejudice – that’s all.”

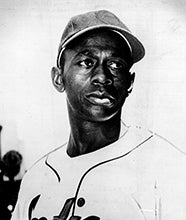

Showcasing megastars such as Satchel Paige, Josh Gibson and Cool Papa Bell, the East-West Games occasionally out-drew the white All-Star Games. In 1939, the Negro Leagues began playing two such exhibitions per season – something the NL and AL would emulate from 1959-62 in hopes of adding money to the players’ pension fund.

Though East-West Games would be played through the summer of 1962 – the final season of the Negro Leagues – they began to lose some of their appeal after Jackie Robinson broke the National League’s color barrier in 1947. Two years later, Robinson would help integrate the NL-AL All-Star Game, when he was joined by former Negro Leaguers Roy Campanella, Larry Doby and Don Newcombe at the Midsummer’s Classic at Ebbets Field in Brooklyn.

An influx of Black stars, particularly in the National League, would infuse the exhibitions with the exciting brand of ball that had made the East-West Games so riveting. And players of color, such as Robinson, Willie Mays, Hank Aaron and Roberto Clemente, would contribute mightily to a dominating stretch that saw the NL post a 33-8-1 record from 1950 through 1987. Since that time, the AL has been on a run of its own, going 27-6-1, to lead the series, 47-43-2, heading into the 2023 contest.

Of all the All-Stars through the years, none shined consistently brighter than Mays, whose five-tool skills enabled him to establish records for most hits (23), runs scored (20), triples (three) and stolen bases (six). As Boston Red Sox Hall of Famer Ted Williams noted, “They invented the All-Star Game for Willie Mays.’’

Williams, whose 12 career RBI are a record, had his moments, too. Perhaps his most memorable one occurred in the 1946 All-Star Game at Fenway Park, when Teddy Ballgame smashed Rip Sewell’s high-arcing, slow-pitch softball-like “eephus’’ toss over the right field fence. “That remains one of my biggest thrills,’’ Williams said decades later.

The All-Star Game also may have been “invented” for Stan “The Man” Musial, whose six homers and three pinch-hit base hits remain standards. Of those homers, none was more important than the one the St. Louis Cardinals legend clubbed in 1955 while leading off in the bottom of the 12th to give the NL a 6-5 victory at Milwaukee County Stadium.

“I think guys like Willie and Stan Musial and Williams shifted into high gear in those games,’’ said New York Giants pitcher Johnny Antonelli, a six-time NL All-Star in the 1950s. “They wanted to show they were the best of the best.”

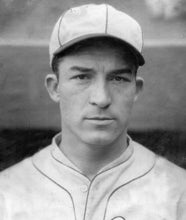

Giants pitcher Carl Hubbell clearly discovered that higher gear in 1934 when he struck out five future Hall-of-Famers in succession. And 65 years later, Red Sox Hall of Famer Pedro Martinez would find it, too, coming within one batter of duplicating Hubbell’s feat.

Through the years, the All-Star Game has produced numerous indelible moments. Fans won’t ever forget Pete Rose bowling over catcher Roy Fosse to score the winning run in the bottom of the 12th of the 1970 game at Cincinnati’s Riverfront Stadium. Or monster home runs off the bats of Reggie Jackson in 1971 and Bo Jackson in 1989. Or two game-saving throws by Pittsburgh Pirates right fielder Dave Parker in 1979. Or Los Angeles Angels center fielder Mike Trout winning his second All-Star Game MVP in 2015 – becoming the first back-to-back winner while joining Mays, Gary Carter, Steve Garvey and Cal Ripken Jr. as the only two-time winners.

Over time, the All-Star Game became an event rather than just a game; a two-day love-fest celebrating baseball’s best. In 1985, a home run derby was added to the lineup, and it became immensely popular, producing unforgettable moments of its own. A celebrity softball game was added, too, as well as a Futures Game to highlight the next generation of stars from the minor leagues.

After a 7-7, 11-inning tie in 2002 in which managers Joe Torre and Bob Brenly ran out of pitchers, then-MLB Commissioner Bud Selig attempted to make the star-studded exhibition more meaningful by announcing the winner would determine which league champion would have homefield advantage in the World Series. This hotly debated move was ended in 2017 by current commissioner Rob Manfred.

This July, the All-Star Game is scheduled to be played for the 93rd time. It’s doubtful even an ingenious promoter like Arch Ward could have envisioned it becoming the extravaganza it has. Despite never realizing his dream of playing for the White Sox, Ward wound up having an enormous impact on the national pastime. His creation became so much more than a one-hit wonder.

Scott Pitoniak is an award-winning journalist and author who resides in Penfield, N.Y. His latest book is “Memories of Swings Past: A Lifetime of Baseball Memories.”