- Home

- Our Stories

- Mudcat Grant helped strengthen the game on, off the field

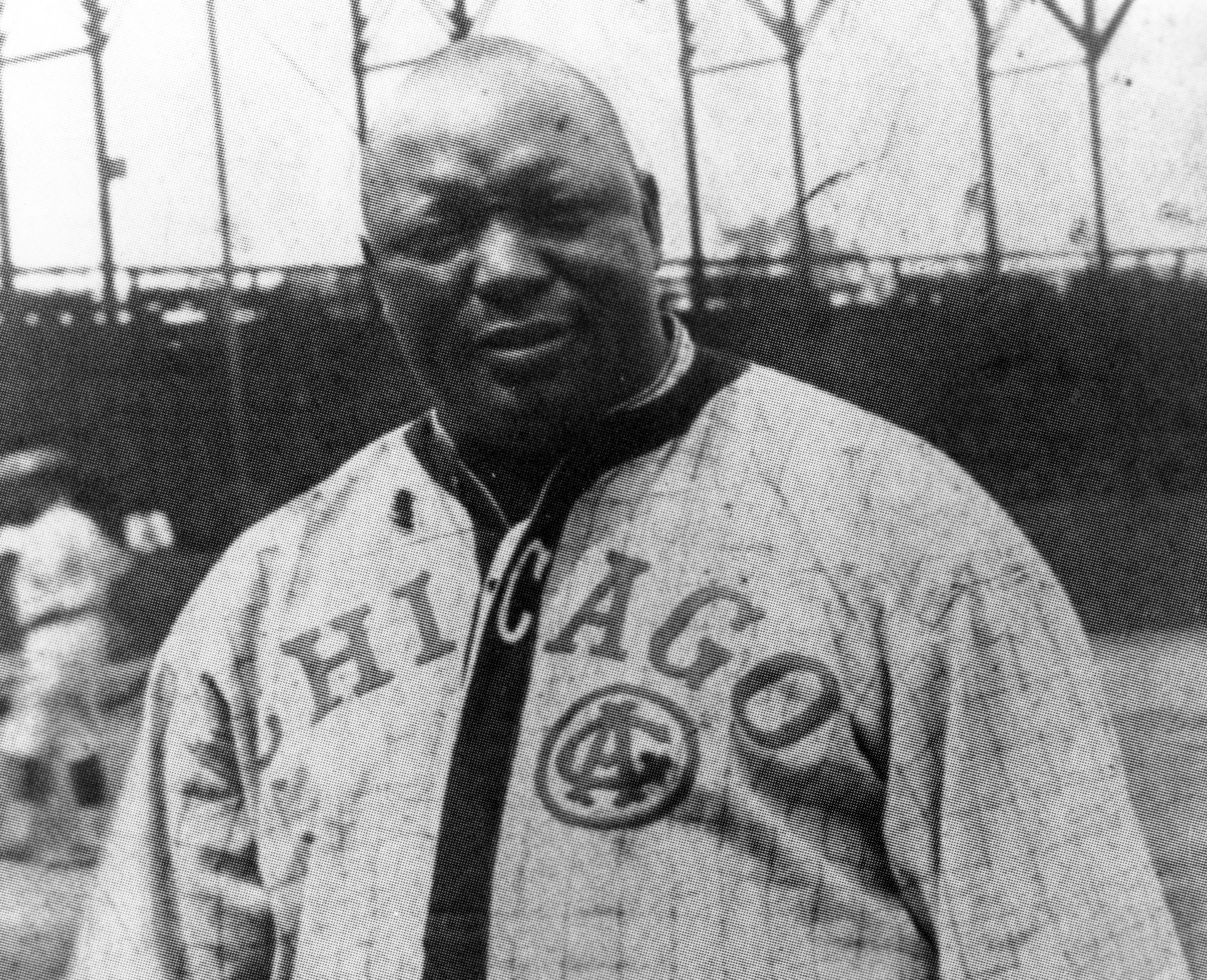

Mudcat Grant helped strengthen the game on, off the field

Over the latter stages of his life, Hall of Famer Buck O’Neil became well known as one of the game’s great ambassadors, from his groundbreaking commentary on Ken Burns’ 1994 documentary, Baseball, to his work with the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum and his inspirational talks with youngsters and adults across the land.

Another man, far less famous, also achieved a niche as one of baseball’s unofficial ambassadors. A star on the field, he followed his career by impacting many of the people he encountered at schools, at the ballpark, and even in Cooperstown.

Be A Part of Something Greater

There are a few ways our supporters stay involved, from membership and mission support to golf and donor experiences. The greatest moments in baseball history can’t be preserved without your help. Join us today.

One cannot tell the full story of Black baseball without telling the story of Jim “Mudcat” Grant. In some ways, Grant’s demeanor and attitude mirrored O’Neil. Both were regarded as fine players – and better men. As with O’Neil, much of Grant’s public recognition would come in his later years, long after he retired as a player.

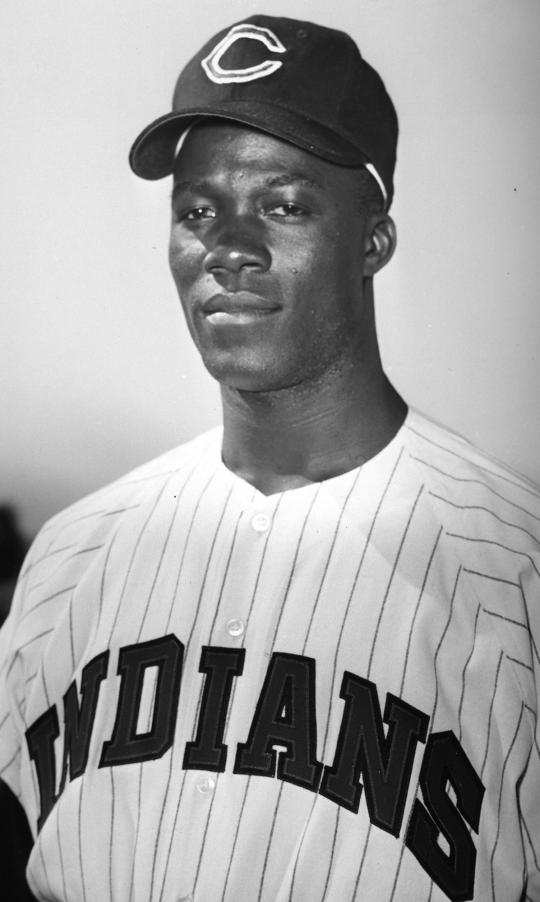

In 1954, a young Jim Grant graduated from his high school, the Moore Academy, in Dade City, Fla. By that time the Negro Leagues, where O’Neil spent all of his playing and managing career, had begun to fade, but Grant found interest from an American League team. Prior to the start of the 1954 season, he signed his first contract with the Cleveland Indians’ organization.

Grant began a four-year climb through the Indians’ minor league system. It was during his minor league tenure that he picked up the nickname of “Mudcat” under erroneous circumstances. One of his teammates, believing for some reason that Grant was from Mississippi, decided to start calling him Mudcat, in deference to Mississippi being known as the “Mudcat State.” Given that, one of Cleveland’s minor league coaches, future Hall of Famer Red Ruffing, started calling Grant “Mudcat,” as well. Initially, Grant tried to correct the situation and explain that “Mudcat” was not his preferred name, but the nickname stuck. And eventually, Grant came to embrace his alter-ego.

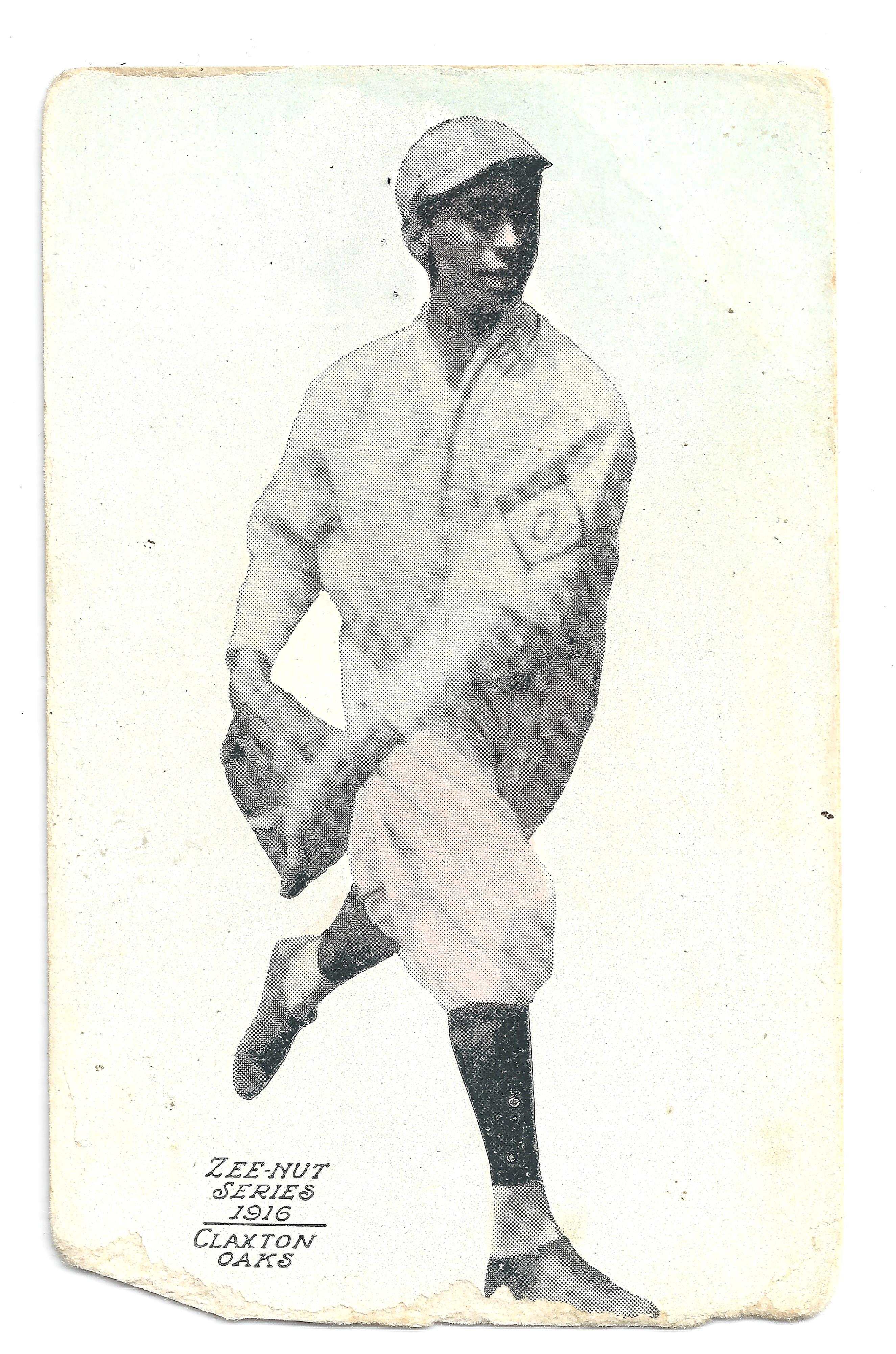

In 1957, Grant moved up to the Triple-A San Diego Padres, the Indians’ affiliate in the Pacific Coast League. Pitching in a hitter’s league, Grant dominated, winning 18 of 25 decisions while spinning an ERA of 2.32. The Padres’ general manager, future Hall of Famer Ralph Kiner, took note of Grant’s talent – and his willingness to learn. “I’ve never seen a young pitcher come along as fast as he has,” said an admiring Kiner. “He wants to learn and is willing to take advice.”

Based largely on the strength of his performance with the Padres, Grant made the Indians’ Opening Day roster in 1958. On road trips, Mudcat was paired with a veteran roommate, Indians star Larry Doby, the first man to break the color barrier in the American League. As it happened, Doby was one of the players that Grant idolized as a youngster. In an interview with the Hall of Fame in 2004, Grant recalled his friendship with Doby. From the start, Doby became a role model to Grant, who also took note of the stress that Doby dealt with as one of the game’s Black pioneers.

“He taught me just about everything,” Grant said. “I know the history of Larry Doby, because late at night Larry would pace. He would yell, he would scream. This is how he would overcome some of the difficulties that he had to go through. I know it was difficult.

“And then he taught me, ‘This is what you’re going to have to face [as a Black player]. You’ve got to face it, and when you cross the white lines, you better win. It ain’t about, ‘Oh, this is so bad for me.’ You better win. Because if you don’t win, [it’s] good-bye, see you later.”

As a minor league player, Grant had done plenty of winning. He had also dealt with many of the realities of Jim Crow segregation, which prevented Blacks from staying at certain hotels, eating in restaurants and even drinking from water fountains. That kind of bigotry was certainly encountered by Doby, both during his Negro Leagues and American League tenures.

In 1958, Grant made a solid transition to the major leagues. Pitching as a combination starter and reliever, he logged 204 innings and won 10 of 21 decisions. It was a more than respectable rookie showing, even if Grant walked more than 100 batters. He then improved his control in 1959 and ’60. It was during that latter season that Grant became involved in one of the most significant controversies of his career.

On Sept. 16, the Indians hosted the Kansas City Athletics at Municipal Stadium. Standing in the bullpen during the national anthem, Grant sang along, but changed the wording of the song in a mocking fashion. Indians bullpen coach Ted Wilks confronted Grant, resulting in the two men exchanging angry words. According to Grant, Wilks called him by the most vile of racial slurs. That prompted Grant to leave the stadium without talking to his manager, Jimmy Dykes, who shortly thereafter suspended Grant for the balance of the season. Wilks apologized for what he said to Grant, but Mudcat would not accept the apology. “I’m sick of hearing remarks about colored people,” Grant told the Cleveland Plain Dealer. “I don’t have to stand there and take it.”

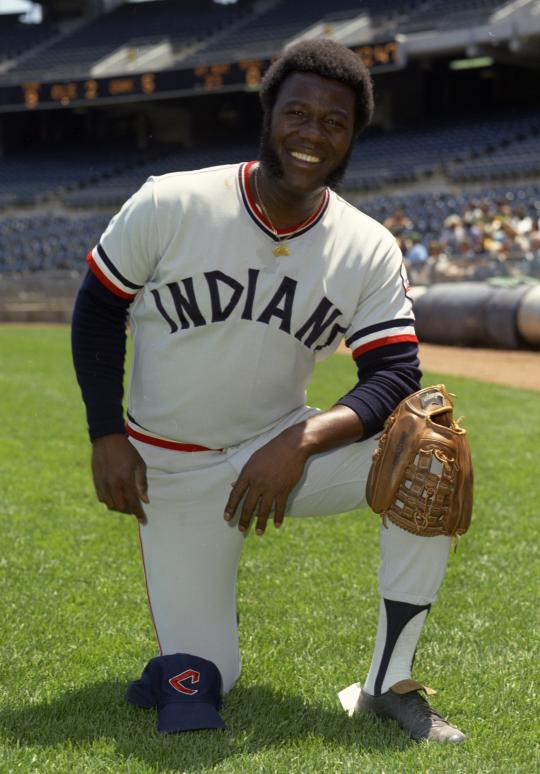

After the season, the Indians fired Wilks and moved Grant into the rotation on a fulltime basis. Grant won 15 games, and then alternated a bad season in 1962 with a good one in 1963, frustrating the Cleveland brass with his inconsistency. A poor start to the 1964 season convinced the Indians to make a change. At the June 15th trading deadline, Cleveland sent Grant to the Minnesota Twins for a package of pitcher Lee Stange and a young infielder/outfielder named George Banks.

The move to Minnesota rejuvenated Grant. He moved into the Twins’ rotation, where he flourished. The situation only improved from there. In 1965, the Twins hired Johnny Sain as their pitching coach. Sain taught Grant how to throw a new pitch – what Grant referred to as a “fast curve.” Helped by the addition to his repertoire, Grant made 39 starts and led the American League in wins (21) and shutouts (6). In so doing, Grant became the first Black pitcher in AL history to reach the 20-win milestone.

With Grant and Hall of Famer Jim Kaat leading the rotation, the Twins advanced to the World Series against the Los Angeles Dodgers. The presence of Sandy Koufax and Don Drysdale made the Dodgers the favorites, but the Twins held their own over a long, tough series. Grant pitched well, earning victories in two of his three starts (and even hitting a home run), but the Twins eventually fell in seven games.

Grant continued to pitch well in 1966, particularly during the second half of the season, but his performance fell off in 1967, largely due to injuries. (The firing of Johnny Sain after the 1966 season likely didn’t help matters, either.) Now 32 years old, Grant became expendable. Twins owner Calvin Griffith traded him and shortstop Zoilo Versalles to the Dodgers for catcher John Roseboro and pitchers Ron Perranoski and Bob Miller on Nov. 28, 1967.

The trade came as a pleasant development to Grant. He felt he had been mistreated by Twins management. Grant spoke out against Griffith, saying that the owner did not treat his Black players as well as the white players. In contrast, the Dodgers, the team that had integrated the National League 20 years earlier, were regarded as one of the game’s most racially progressive organizations. Dodgers manager Walter Alston moved Mudcat to the bullpen, where he excelled.

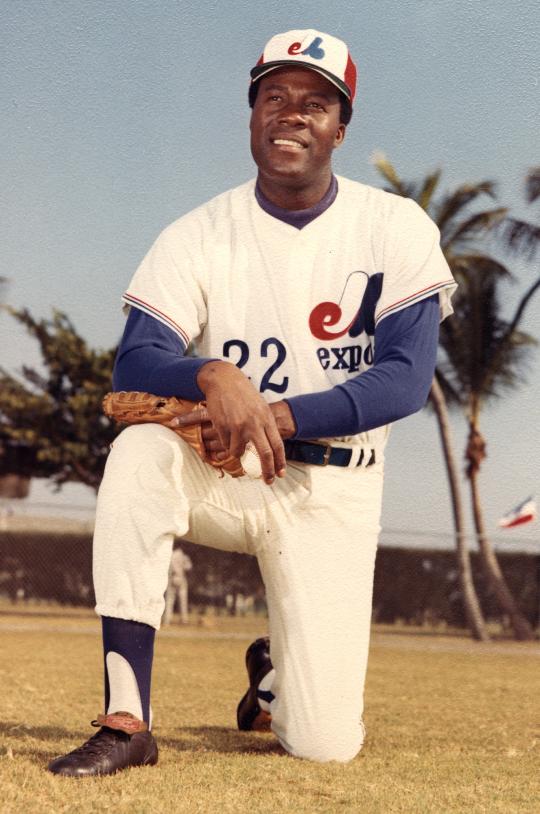

Grant did his job well for the Dodgers in 1968, but his age worked against him when the team considered whom to protect from the upcoming expansion draft. The Dodgers hoped that neither of the two National League expansion teams would take Grant, but the Montreal Expos could not resist.

The following February and March, Grant and the rest of the new Expos players reported to Spring Training in West Palm Beach, Fla. One night that spring, Montreal’s veteran shortstop, Maury Wills, went to a bar with a sportswriter and a local photographer. Wills was almost immediately asked to leave by a bar employee, who explained that the establishment did not serve “colored people.” This was happening in 1969, or five years after the passing of the Civil Rights Act.

Grant, who had experienced similar types of racism throughout his career in the 1950s and 60s, could not let the Wills situation go without doing something. He wrote a letter of protest to Florida Governor Claude Kirk. As Grant told the Associated Press, “Wills is an outstanding citizen of this country. He should be accepted as a citizen, not as a Black man, who has to be told that he can’t do this or that.” The incident served as a reminder that while civil rights laws had changed, their application to everyday life had not.

On the mound, Grant pitched well enough that spring to become the first Opening Day starter in Expos history. While Grant’s reputation was well established, he was also 33 years old, making him less than ideal for a building expansion team. In June, the Expos traded Grant, sending him to the St. Louis Cardinals, where he finished out the season pitching in middle relief.

Grant’s career appeared to have hit a crossroads. But then came the break that he needed. That winter, the Cardinals sold Grant to the Oakland A’s, who needed help in the bullpen. The A’s eventually called on Grant to serve as their late-inning fireman, a role he had never before handled. Making the transition with ease, Mudcat racked up 24 saves and a terrific ERA of 1.82.

Grant performed another important service for Oakland. One of his bullpen mates was a young right-hander named Rollie Fingers, who had struggled as a starter before moving to a relief role. Grant worked with Fingers, giving the 23-year-old advice on how to prepare to enter a game, including instructions on warming up properly. Grant’s counsel helped Fingers make the transition to relief pitching, setting the stage for him to become Oakland’s No. 1 reliever and a Hall of Famer.

To the surprise of many, Grant did not last the 1970 season in Oakland. In mid-September, the A’s traded Grant to the Pittsburgh Pirates for a young outfield prospect, Ángel Mangual. The move stunned the Oakland beat writers, who believed that A’s owner Charlie Finley had become angry with Grant for making a facetious remark on the radio about ownership “interfering” with manager John McNamara. It was nothing more than an inconsequential and humorous jab, but Finley took it seriously. Serving as his own general manager, Finley orchestrated the trade that sent Grant to Pittsburgh.

Grant fit in well with the Pirates, a racially-integrated team that was headed toward a berth in the postseason. The Pirates soon clinched the National League East, as Grant pitched well down the stretch. He remained effective for the Bucs in 1971, but the team’s deep bullpen eventually made him expendable. In early August, the Pirates sold Grant’s contract, sending him back to Oakland, where Finley had apparently forgiven Grant for his 1970 “transgression.”

Providing the A’s with another quality pitcher at the back end of their bullpen, Grant put up an ERA of 1.98 ERA. While he had missed out on a division title with the Pirates, he was now headed to the postseason with the A’s, who won the American League West before losing the ALCS to the powerhouse Baltimore Orioles.

Although Grant appeared to have plenty left in his 36-year-old tank, he was once again dismissed by Finley. After the season, Finley released Grant, not because of his pitching, but simply because he didn’t want to give him the kind of sizeable contract a veteran pitcher would command.

Rather shockingly, no other team would give Grant a major league contract for 1972. So he settled for a non-roster invitation from his first organization, the Indians, but did not make the cut. The Indians offered him a minor league deal to pitch at Triple-A Portland, but Grant rejected the move. He eventually signed with the minor league Iowa Oaks, in the hope that some big league team would come calling. That never happened, motivating Mudcat to retire. He left the game with a record of 145 wins and an ERA of 3.63 over 14 seasons.

After his playing days, Grant continued to pursue some of his other interests while also maintaining his connection to the game. As the longtime front man for a group called “Mudcat and the Kittens,” he often sang at nightclubs around the country. He also ventured into broadcasting, first with the Indians and then the A’s.

In the 1980s, Grant branched out into community service. He began operating a nationwide program called “Slug-Out Illiteracy, Slug-Out Drugs,” in which he made public speaking appearances and talked about the value of education while stressing the importance of avoiding drugs. Grant also tried to help former players struggling with either drug problems, financial concerns, or medical issues, as part of his work with the MLB Players Alumni Association.

One of the players Grant tried to help was retired slugger Leon Wagner, who had struggled in his post-playing days, eventually becoming destitute and homeless. Mudcat set Wagner up with jobs in fantasy camps and even arranged apartments for him to live in, but Wagner ultimately resisted the help and returned to a life of addiction before dying from drug abuse in 2004.

In his later years, Grant continued to work hard on issues that mattered to him.

One of them was the decline of Black participation in baseball in the 1990s and 2000s. In February of 2004, Grant and his former Pirates teammate, Al Oliver, came to the Hall of Fame to participate in a special program centered on Black History Month. Grant and Oliver interacted wonderfully with fans in the Museum’s Bullpen Theater, giving important insight into baseball’s struggle to connect with Black youth, while also entertaining fans with stories from their playing days.

Grant also became involved with a 2006 book project called The Black Aces. Written with veteran author Tom Sabellico, the book details the Black pitchers who have won 20 or more games in a single season. The publication of the book prompted President George W. Bush to invite Grant and other members of the “Black Aces” to the White House for a 2007 ceremony celebrating Black History Month.

In his last few years, Grant suffered from declining health, which limited his ability to travel and spread the word about the history of Black baseball. In June of 2021, Grant passed away at the age of 85.

There’s no doubt that Grant’s death left a void in the game, but there’s also little doubt that he contributed forcefully to an appreciation of the accomplishments of Black players, both for older fans and youngsters just beginning to experience the game. It’s part of a legacy that included a fine pitching career and a selfless desire to help others – a legacy for which Jim “Mudcat” Grant deserves to be long remembered.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum