- Home

- Our Stories

- Leon Wagner fought battles on and off the field

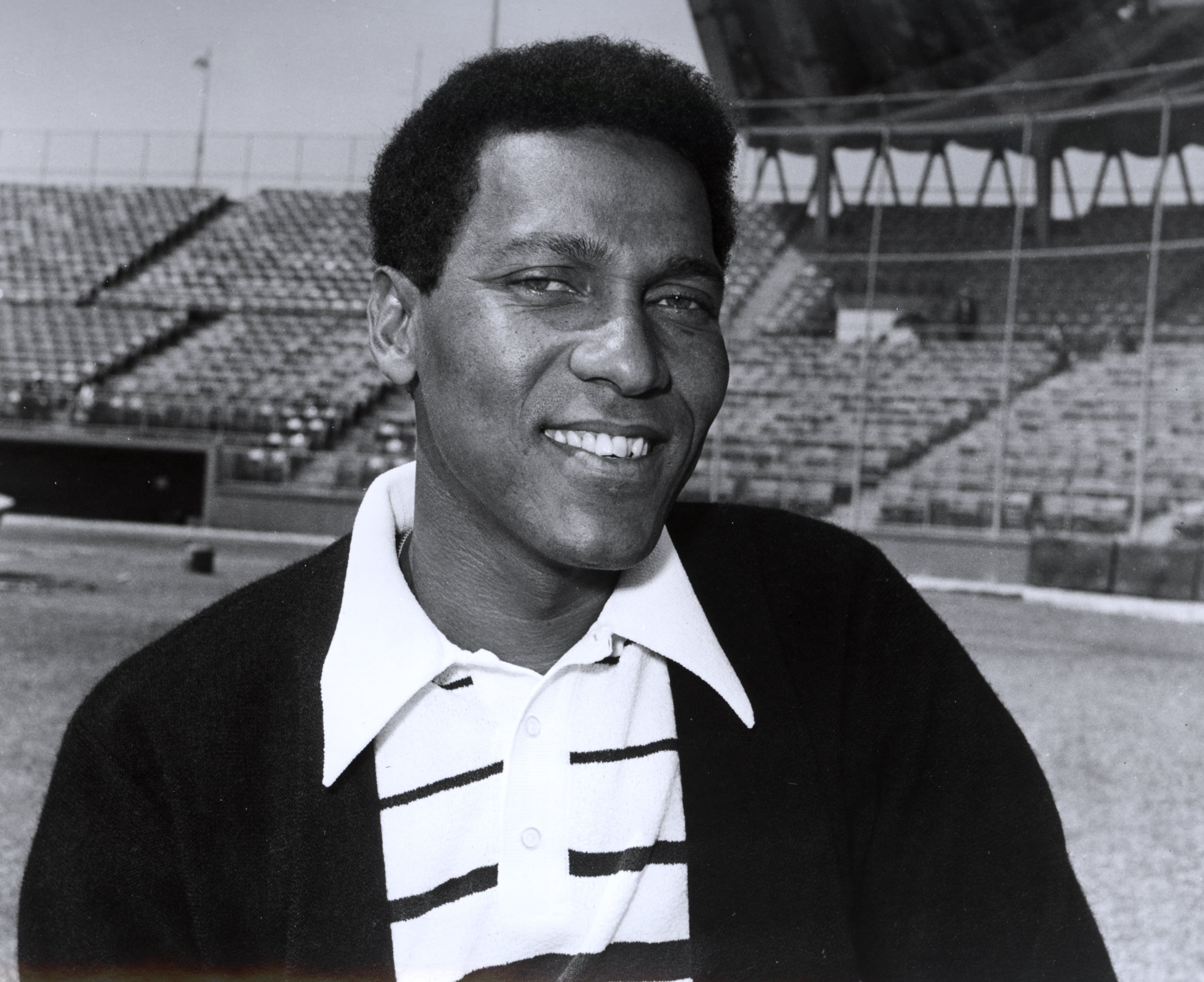

Leon Wagner fought battles on and off the field

For every Buck O’Neil who becomes a success and a media favorite after his playing days, there are numerous players who struggle through hard times. Financial problems, an inability to come to grips with the end of a playing career, drug and alcohol addiction and just plain bad luck can all factor into the morass of heartbreak afflicting a player after retirement.

One of the most disheartening of those stories involves former major league outfielder Leon Wagner.

STORIES OF BLACK BASEBALL

Stories that highlight the lives and experiences of Black ballplayers through key moments in history, artifacts and baseball cards.

Ironically, Wagner’s baseball life started in almost dreamlike fashion. As a youth, he was playing on a local sandlot field, located in the town of Inkster, Mich., when he caught the eye of New York Giants scout Ray Lucas. Not long after, Lucas signed Wagner to his first professional contract. From there, Wagner received an assignment to Danville, Illinois, of the Class D Mississippi-Ohio Valley League.

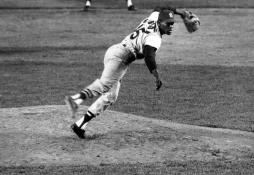

In contrast to many first-year players, Wagner made a smooth transition to professional ball, hitting 32 home runs with 164 RBI between two minor league teams. The act of hitting seemingly came easy for Wagner, but it was in the field that he struggled mightily. Playing the outfield, he committed an unsightly total of 16 errors.

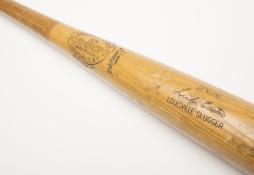

With his ferocious and power-packed left-handed swing, Wagner continued to dominate minor league pitching over the next two summers. Playing in the Class C Northern League in 1955, he batted .313 and led the league with 29 home runs. He would show even more power the next season in the Class B Carolina League, where he blasted 51 home runs and drove in 166 runs, both eyepopping totals.

As well as Wagner played during his first three professional seasons, day-to-day life did not come easy, largely because of the racism that he faced first-hand. In one especially harrowing game on the road, Wagner was confronted by a white fan who was shouting racial insults from the stands. The fan, who was toting a rifle, made it clear that Wagner should not catch the next fly ball hit in his direction. If he did, something bad would result. Out of legitimate fear that his life was in danger, Wagner intentionally dropped the next fly ball that was hit toward him.

Another challenge came Wagner’s way in the mid-1950s. That’s when the U.S. Army drafted him into service. Although the Korean War had ended by that point, Wagner still had to serve 14 months at Fort Carson, Colo., where he drove a military jeep. He missed the entire 1957 minor league season, delaying his development and likely stalling his eventual arrival in the major leagues.

In 1958, Wagner returned to professional baseball. With the Giants having relocated from New York to San Francisco, the franchise’s top affiliate at Triple-A now resided in Phoenix, Ariz. Not missing a beat after a one-year absence from the game, Wagner adjusted well to Triple-A pitching quite nicely, hitting .318 with 17 home runs over his first 65 games. Those numbers earned him a midseason call-up to San Francisco.

The Giants needed some help in leftfield, where veteran Hank Sauer was now 41 years old and near the end of his career. On June 22, Wagner made his major league debut. Becoming part of a left field platoon with Sauer, Wagner batted .317 with 13 home runs in 74 games, or roughly the equivalent of a half-season. With a full season in San Francisco, Wagner might have received some consideration for Rookie of the Year honors. But even with just four months of time in a Giants uniform, Wagner made a strong impression. As Giants executive Garry Schumacher said in an interview with the San Francisco Examiner, the young Wagner reminded him of a “left-handed Hank Aaron.”

Such high praise portended a bright future for Wagner in San Franciso. Or so it seemed. Unfortunately, Wagner’s fielding problems, a concern in the minor leagues, remained a source of contention in 1959. Wagner denied claims that he was a poor defensive outfielder, but Giants manager Bill Rigney, among others, felt that he made too many errors and did not grasp the fundamentals of playing left field. Rigney benched Wagner in favor of another young outfielder, Jackie Brandt. The colorful Brandt wasn’t nearly the hitter that Wagner was, but he outplayed his outfield counterpart that summer and received most of the playing time in left field. Playing sparingly, Wagner batted just .225 with five home runs.

Despite Wagner’s talent and youth, he quickly fell out of the team’s plans. After the 1959 season, the Giants traded Wagner and infielder Daryl Spencer to the St. Louis Cardinals for former All-Star second baseman Don Blasingame. Wagner reacted to the trade with bitterness. He believed that Rigney and one of his coaches, Salty Parker, spent far too much time focusing on his fielding woes while exaggerating his inability to handle the fundamentals of outfield play.

With the Cardinals, Wagner faced another outfield logjam. Hall of Famer Stan Musial occupied left field, Wagner’s primary position. Joe Cunningham, who batted left-handed like Wagner, played in right field. With the outfield corners filled, the Cardinals used Wagner as a backup outfielder and pinch-hitter. Concerned that he was not receiving the regular at-bats that he needed, the Cardinals sent him to Triple-A Rochester in mid-season, allowing him to play every day.

Wagner hoped for a breakthrough in the spring of 1961, but it would not come – at least not in St. Louis. Prior to Spring Training, the Cardinals traded Wagner to a minor league team, the Triple-A Toronto Maple Leafs. And then during the spring, the Maple Leafs sent Wagner to one of the new American League expansion franchises, the Los Angeles Angels, in a straight-up trade for fellow outfielder Lou Johnson.

Interestingly, the trade reunited Wagner with his former Giants nemesis, Bill Rigney. Now managing the expansion Angels, Rigney held no grudges against Wagner. Instead, he made the Angels’ new acquisition his regular left fielder. Wagner would reward the newfound show of confidence, hitting .280 with 28 home runs and a .517 slugging percentage. He also showed improvement in the outfield, recording 12 assists, the best total of his career.

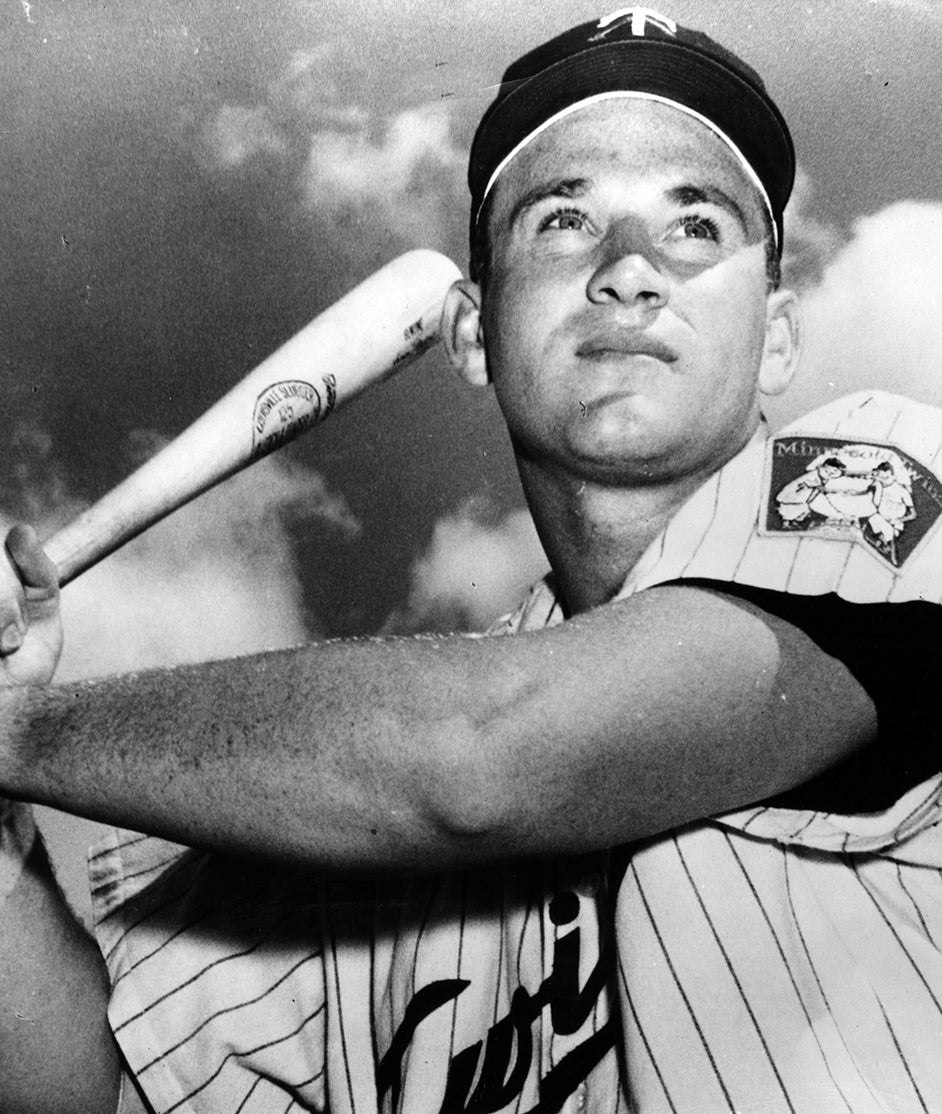

The 1961 signaled the start of Wagner’s peak. He would become a star in 1962, opening the season by hitting nine home runs in his first 18 games. By the end of the summer, he had hit 37 home runs and compiled a .500 slugging percentage. The sportswriters took note, giving Wagner significant support in the American Leage MVP voting. Wagner finished fourth in the balloting, ranking behind only Mickey Mantle, Bobby Richardson and Harmon Killebrew. It was a stunning finish for a player on a second-year expansion team.

Not only did Wagner emerge as a key player for the Angels, but he also became a popular figure with the Southern California media. Writers following the team appreciated Wagner’s outgoing personality, his sense of humor and his willingness to give offbeat answers to questions. The fans in Los Angeles also enjoyed Wagner’s style of play, especially when he took his turn at bat. While in the batter’s box, Wagner typically went through a series of unusual movements and gestures. Those gyrations earned him the nickname, “Daddy Wags.”

Wagner’s on-field success led to a business venture off the field. He invested money in a local clothing store, becoming its part owner. Wagner’s involvement allowed the store to use a creative tag line, “Get your rags from Daddy Wags.”

On the field, Wagner put up another big season in 1963, clubbing 26 home runs, batting .291 and compiling an OPS of .809. He earned a third selection to the All-Star Game, after having been picked for both of the All-Star games in 1962. Wagner had apparently found a long-term home in Los Angeles.

Then came an unexpected development in December of 1963. In a move that no one could have seen coming, and few really understood, the Angels traded the productive and popular Wagner, sending him to the Cleveland Indians for pitcher Barry Latman and a player to be named later, which turned out to be aging first baseman Joe Adcock.

The trade left Wagner feeling crushed. “I don’t see how anybody could be happy over leaving the Angels,” Wagner told the Los Angeles Times. “I’m going to miss the players. I’ll miss [Rigney] more than anything. He’s the man who brought me back from the minors and I’ll never forget it.”

The trade also shocked Angels fans and media. Why would the Angels trade their best power hitter and arguably their most popular player? Some of the Angels beat writers tried to come up with explanations. One theory suggested Angels management was upset because the team had loaned him money to support his clothing store, which was struggling financially and would eventually go out of business. Another theory had to do with Wagner’s relationship with Angels general manager Fred Haney, whom he did not like. In an on-the-record interview, Wagner had once described Haney as “a sort of [Nikita] Khrushchev,” a reference to the first secretary of the Communist Party and leader of the Soviet Union.

The Angels would come to regret the trade, while the Indians would benefit. In his first year with Cleveland, Wagner hit 31 home runs, stole a career-best 14 bases and again received some voting support in the league MVP race.

Wagner continued to hit well in 1965 and ’66. Not surprisingly, he became a favorite of the Cleveland media, which appreciated his outlandish quotes and bold predictions. In an interview with writer Hal Lebovitz of the Cleveland Plain Dealer, Wagner predicted that he would break the single-season home run record. “If Roger Maris hit 61,” Wagner said, “I can hit 70.”

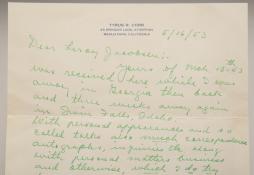

In Cleveland, a local sports columnist dubbed Wagner with a new nickname, “The Good Humor Man,” a reference to the company that sold ice cream to neighborhood children out of a truck. Fans at Municipal Stadium in Cleveland certainly appreciated Wagner’s willingness to sign autographs and talk with them. In response, the Indians received numerous requests from groups and organizations that wanted him to make public speaking appearances.

Wagner posted three excellent seasons for the Indians before starting to show some decline in his game in 1967. That summer, he lost his job as an everyday regular. His new manager, Joe Adcock, made him part of a platoon with another fan favorite, Rocky Colavito. He hit only 15 home runs, his lowest total since his time in St. Louis.

Reporting to Spring Training in 1968, Wagner hoped that he could regain his starting job in left field. The optimism of spring soon gave way to the realities of the regular season. He played intermittently for another new manager (Alvin Dark), didn’t hit well, and then saw his role reduced to pinch-hitting. By the middle of June, the Indians decided to part ways with Wagner, trading him to the Chicago White Sox for outfielder Russ Snyder. With Chicago, Wagner hit for a good average (.284) but exhibited little power, hitting just one home run.

In the winter of 1968, the White Sox sold Wagner to the Cincinnati Reds, but he would never play a game for the franchise. Just before the start of the 1969 season, the Reds returned Wagner to the White Sox. With no room on their roster, the White Sox released Wagner immediately, putting him out of work for the first time since turning professional.

In May, Wagner signed a minor league contract with his original team, the Giants, who assigned him to Triple-A Phoenix. The Giants called him up in September, gave him a few at-bats, and then released him after the season. That essentially ended his career. After a brief minor league stint with Hawaii in 1971, Wagner retired from baseball.

Given his personality, Wagner seemed like a player who would do well in his career after baseball. But his clothing store had long since gone out of business. He found employment on other areas, working as a car salesman in Honolulu and then taking a job in public relations for a racetrack near Los Angeles.

Wagner used his connections to become part of the Hollywood scene. He took on an acting role in the 1974 film, A Woman Under the Influence, working under the direction of the acclaimed John Cassavetes. Two years later, he was offered a significant part in the film, The Bingo Long Traveling All-Stars, which portrayed life in the Negro Leagues during the 1930s. The entertaining and humorous film did well at the box office, even though it drew criticism for being inaccurate in exhibiting life in Negro Leagues baseball. Sadly, it would also turn out to be Wagner’s final appearance in a film.

Wagner’s life soon spiraled badly. Without a regular income, he struggled financially. He also developed a drug habit, which only exacerbated his problems.

Wagner’s son, Leon, Jr., and daughter, Lei Juana, tried to help him, but he repeatedly turned back their offers. A local realtor in Los Angeles eventually set Wagner up with an apartment, deducting his monthly rent from the money he received through his pension from Major League Baseball. The arrangement worked for a while, but when the realtor realized that Wagner had returned to using drugs, he evicted him from the apartment.

The Baseball Assistance Team (BAT) also tried to help Wagner. The head of BAT, Earl Wilson, and BAT board member Jim “Mudcat” Grant would give him food money and arrange for him to spend a few nights in a hotel. But Wagner would inevitably return to the streets. Another one of BAT’s board members, Lou Johnson, the same player for whom Wagner had once been traded, made efforts to reach out to his fellow MLB alumnus. Johnson arranged for Wagner to be flown to Florida, where he would enter a substance abuse center. Wagner never showed up for the flight and never checked into the rehab center.

One of his former teams, the Indians, invited Wagner to appear at their annual fantasy camp. Initially, Wagner said he would take part, but then at the last minute, he bowed out. Years later, in 2001, the Indians wanted to include him in a celebration of the top 100 players in franchise history, but the team was unable to contact him.

There was a good reason behind the Indians’ inability to reach Wagner. By 2001, he was living exclusively in the streets, without a true home and with no money. Three years later, during the winter of 2004, Wagner’s lifeless body was found in an old electrical shed that he had made into his living quarters. He was just 69 years old.

Wagner’s downturn and ill-fated life have inevitably led to theories about what caused his problems. Some former players believed that Wagner never recovered from the shock of being traded by the Angels, the team where he enjoyed his peak years in the major leagues. Others felt that Wagner’s lack of a college education may have hurt him. With regard to his short career in Hollywood, some say that he lacked the discipline needed to succeed as an actor.

One former player, the aforementioned Lou Johnson, offered up his own thoughts about Wagner’s fate in an interview with Bill Plaschke of the Los Angeles Times.

“Remember the first time they sent astronauts into space, and they weren’t afraid until they landed in the ocean?” Johnson asked Plaschke. “That’s what happens to some old ballplayers, particularly from our era, particularly African Americans. When we retire, it’s like landing in the middle of the ocean without a rowboat.”

If you know of a former player in need of help, contact the Baseball Assistance Team at 212-931-7822, or send an email to BAT@mlb.com.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum